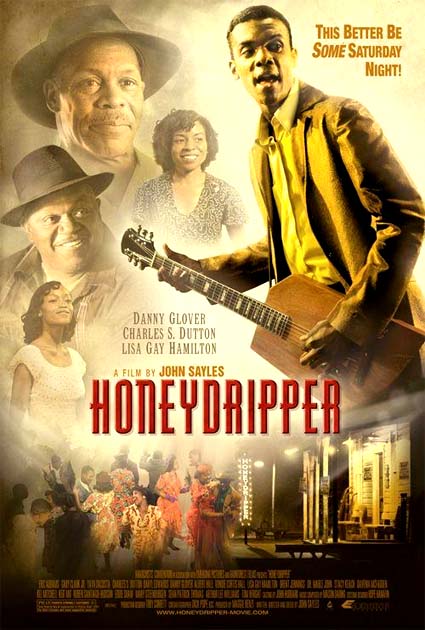

HONEYDRIPPER (2007, directed by John Sayles, 123 minutes, U.S.)

HONEYDRIPPER (2007, directed by John Sayles, 123 minutes, U.S.)

BY DAN BUSKIRK FILM CRITIC

After the recent long-winded political rants Silver City and Sunshine State, it’s a relief to see indie film Godfather John Sayles pursue this more conventional story, of Danny Glover’s struggle to keep his Alabama juke joint open in the year of 1950. At its best, blues fable Honeydripper reminds one of his early 90’s hit Passion Fish; both films transcend their conventional stories with perceptive performances and a smattering of Southern regionalism. Yet even with its de-politicized story, Sayles still winds up stepping in his own hoodoo.

Sayles’ highly-lauded 1996 film Lone Star probably best realized the director’s ambition to entertain while illustrating how politics turns personal. It has been a spectacular flame-out since — in the years that followed, his films became more and more politically shrill, his gift for human observation quickly withering while his characters became empty embodiments of political philosophies. As noble as Sayles’ politics were, it wasn’t entertainment. With his increasingly arch, metaphor-ridden rhetoric shoe-horned into the mouths of political sharpies and beleaguered working stiffs, Sayles seemed to be parading a particularly horrible artistic sin: He had become a proud populist who had completely lost touch with the rhythms and language of the people he was portraying. It’s tough to watch a filmmaker whose films you have consistently enjoyed (particularly the Union Western Matewan and his scripts for Corman quickies Alligator and The Lady In Red) turn downright excruciating, like an uncle who can’t stop telling you how the whole world should be run.

Sayles distraction from the political allows room to demonstrate his gift for character, and while actors like Danny Glover, Charles Dutton and newcomer musician Gary Clark Jr. act their asses off, never for a minute does Sayles’ flowery and colorful dialogue let you believe you are seeing reality unfold. The set-up is quickly established. Glover and his sidekick Dutton conspire to get the popular Guitar Sam to play at their dilapidated juke joint in order to make back rent. Meanwhile a cocky young six-stringer hops off a freight car and is tossed into a work-gang before he get a chance to open his guitar case. Are they destined to meet? You’re pretty sure they will once Glover’s club The Honeydripper is described as being “down by the crossroads.” Might Ralph Macchio be wandering nearby?

juke joint in order to make back rent. Meanwhile a cocky young six-stringer hops off a freight car and is tossed into a work-gang before he get a chance to open his guitar case. Are they destined to meet? You’re pretty sure they will once Glover’s club The Honeydripper is described as being “down by the crossroads.” Might Ralph Macchio be wandering nearby?

Sayles’ writing has become increasingly theatrical, his people never at a loss for lyrical and concise musings on their lot in life. Here, writing for a mostly African-American cast, this stilted talk veers uncomfortably close to the one-dimensional stereotypes of cinema’s past. Add in a script full of knife fights, card games, stolen hooch, cotton-picking, chicken-frying, man-eating fat ladies, and somehow Honeydripper’s good intentions also contains a season of Amos ‘n Andy episodes within its two hours. Keb’ Mo’ even plays a blind street musician who can transcend space and time. For crying out loud, didn’t Sayles get the memo about eschewing those “Magical Negroes”?

So OK, the main course is burnt — you aren’t going to eat the side dishes? Every 15 minutes or so the film stops dead to give the main stars a solo spotlight for their dramatic moment. With acting talent like what is assembled here, this is no small plus. Glover imagines what it must have been like when the first slave dared to touch the Master’s piano, Dutton recalls an unfaithful lover getting burned with hot grits (the act later known as “getting Al Greened”) and affable young singer Gary Clark gets to make like Guitar Slim and jump on the cars in front of the club with his 50-foot guitar cord. They are fleeting moments of pleasure, but at least they raise Honeydripper at tad above Sayles’ 21st Century artistic freefall.