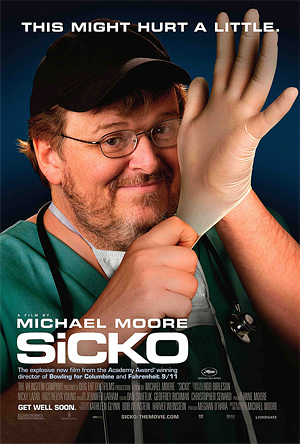

(SiCKO, Directed by Michael Moore, 113 min. USA)

(SiCKO, Directed by Michael Moore, 113 min. USA)

BY JONATHAN VALANIA EDITOR

As Michael Moore declares over the kind of gallows-humored opening montage that has since become his trademark, SiCKO, his invasive procedural on the American health care system, is not about the 50 million uninsured people in the richest country in the world, or the estimated 18,000 who die each year because they can’t afford to seek care. Nor is this film about the fact that the United States’ health care system is the 37th best in the world (woo-hoo!), right behind Slovenia. No, this film is about the winners and the happy-enders, the 250 million Americans who have health insurance and not a care in the world. Or so they think.

The first third of the film is a sad parade of health insurance hard-luck stories: The insured 50-something couple, so exhausted physically and financially by battles with cancer and heart disease that they had to sell their house and move into their daughter’s spare room. The insured woman with cervical cancer who has to sneak across the Canadian border get the treatments her U.S. provider won’t approve because she is simply “too young to have cervical cancer.” The women knocked unconscious in a wicked car accident who is later informed that the life-saving ambulance trip would not be paid for by her insurer because the unconscious women did not approve the ambulance before it took her away. There is the man whose life could have been saved by a $500,000 procedure, but his wife’s health insurer refused to pay for it — even after she requested a meeting with the board of trustees and literally begged them to save her husband’s life. He died three months later. Then there’s the three-year-old with the dangerously high fever whom the Emergency Room staff refused to treat because her mother’s insurers insisted that the girl be taken to an “in-network” hospital for treatment. She died in the ambulance.

OK, you say, but those are just people that fell through the cracks and Moore, in classic fashion, is exaggerating these exceptions and misrepresenting them as the norm. Not necessarily, says a guy whose job used to be to comb through the insurance applications of the insured and look for any technicality that could be used to deny payment and cancel policies of anyone making a claim. “You’re not slipping through; somebody made the crack and swept you in it,” he says. There is also the riveting Congressional testimony of a physician who once served as a medical advisor to a major HMO. She could no longer continue, she said, when the company started offering six-figure bonus incentives for the doctor who could save the company the most money, and it became clear that the more care you denied the more money you would make. She is pretty sure, she told the committee, that at least one policy-holder died as a result of her denying care.

How did this happen, you ask? How did the health care system become about restricting medical care instead of dispensing it? Why, Richard Nixon, of course. Moore plays a Feb. 17, 1971 recording of an Oval Office conversation between Nixon and aide John Ehrlichman about “Edward Kaiser’s Permanente thing” and their “new” way of running health care as a for-profit concern.

John Ehrlichman: “On the … on the health business …?

President Nixon: “Yeah.”

Ehrlichman: “… we have now narrowed down the vice president’s problems on this thing to one issue and that is whether we should include these health maintenance organizations like Edgar Kaiser’s Permanente thing. The vice president just cannot see it. We tried 15 ways from Friday to explain it to him and then help him to understand it. He finally says, ‘Well, I don’t think they’ll work, but if the President thinks it’s a good idea, I’ll support him a hundred percent.'”

President Nixon: “Well, what’s … what’s the judgment?”

Ehrlichman: “Well, everybody else’s judgment very strongly is that we go with it.”

President Nixon: “All right.”

Ehrlichman: “And, uh, uh, he’s the one holdout that we have in the whole office.”

President Nixon: “Say that I … I … I’d tell him I have doubts about it, but I think that it’s, uh, now let me ask you, now you give me your judgment. You know I’m not to keen on any of these damn medical programs.”

Ehrlichman: “This, uh, let me, let me tell you how I am …”

President Nixon: [Unclear.]

Ehrlichman: “This … this is a …”

President Nixon: “I don’t [unclear] …”

Ehrlichman: “… private enterprise one.”

President Nixon: “Well, that appeals to me.”

Ehrlichman: “Edgar Kaiser is running his Permanente deal for profit. And the reason that he can … the reason he can do it … I had Edgar Kaiser come in … talk to me about this and I went into it in some depth. All the incentives are toward less medical care, because …”

President Nixon: [Unclear.]

Ehrlichman: “… the less care they give them, the more money they make.”

President Nixon: “Fine.” [Unclear.]

Ehrlichman: [Unclear] “… and the incentives run the right way.”

President Nixon: “Not bad.”

In 1973, Richard Nixon signed the HMO Act, ushering in the modern era of American health care. Today, Kaiser-Permanente is the largest HMO in the U.S.

The film’s middle third is a globe-trotting tour of socialized medicine wherein Moore compares and contrasts the U.S. with England (the National Health takes care of everyone and doctors live in million-dollar homes in London), France (number one health care system in the world where the doctors make house calls day or night, cheerfully, and government-paid nannies come by a couple times a week to help with the housework and do the laundry for mothers of newborns) and Canada.

For Canada, Moore plays a very sly trick. He interviews an elderly Canadian couple who tell him they applied for special insurance that would deliver them from the evil of the American health care system if, God forbid, something bad happened to either of them during their few-hour trek across the border to talk to Moore. Despite all the horror stories we have just witnessed about US medical care, we still laugh at this likable elderly couple who, like most elderly couples, feel very vulnerable in the world and protect themselves with irrational fears. It’s as if Moore is saying to us: Their fears of American health care are just as irrational as our fears of a Canadian-style health care system.

Actually, those two Canucks should be afraid, very afraid. Consider the unnamed American carpenter Moore interviews at the beginning of the film who accidentally sawed off his thumb and ring finger. Uninsured, the hospital offered him a deal: Put the thumb back on for $60,000 or the ring finger for $12,000 — with his family’s financial stability hanging in the balance, he went with the ring finger.

Arguably, no visual better illustrates the Darwinian barbarity of American health care than security cam footage of an ambulance dumping a disoriented homeless woman — still in her hospital gown, the name of the hospital cut off her hospital-issued ID bracelet — on LA’s Skid Row. Moore runs the footage in silent slo-mo and we watch the woman amble in a daze into oncoming traffic, the blurry film quality only adding to the pathos and teary-eyed verite of watching mankind at its lowest ebb. And it is then you come to grips with the cruel bargain we have struck: when health care becomes prohibitively expensive, life becomes increasingly cheap — until finally it’s worth nothing at all.

security cam footage of an ambulance dumping a disoriented homeless woman — still in her hospital gown, the name of the hospital cut off her hospital-issued ID bracelet — on LA’s Skid Row. Moore runs the footage in silent slo-mo and we watch the woman amble in a daze into oncoming traffic, the blurry film quality only adding to the pathos and teary-eyed verite of watching mankind at its lowest ebb. And it is then you come to grips with the cruel bargain we have struck: when health care becomes prohibitively expensive, life becomes increasingly cheap — until finally it’s worth nothing at all.

How else to explain the trio of 9/11 rescue volunteers who labored in the smoking rubble of the World Trade Center looking for survivors until they literally couldn’t breathe anymore, only to be denied care by the fund created by New York Gov. George Pataki to treat the scores of 9/11 volunteers who got sick? As Moore illustrates, while the 9/11 volunteers were quietly getting the shaft, the TV news reports were flush with images of Republican Congressmen visiting Gitmo and seeing first-hand the wonderful health care the prisoners receive. So basically, the guys who caused 9/11 — if you follow the administration’s logic — get unconditional access to top-flight medical care, but the people who tried to rescue survivors that day, well, they just might have to go without. Pow!

It is here that Moore, the great PT Barnum of the Left, stages a grand piece of political symbolism: He loads up a couple of boats with the three 9/11 rescuers and the woman who had to move into her daughter’s spare room and sets sail for Gitmo. It’s like a Cuban boatlift in reverse, taking our tired, our sick and our poor to a place more merciful. That winds up being a hospital in Havana — after Moore wisely decides against trying to navigate his way through the minefield that rings Guantanamo Bay — where all of Moore’s passengers are given the care they need gratis, courtesy of the people of Cuba. And so this tragic story has a happy ending, even for Moore, who is seen in the galumphing up the steps of the Capitol to get his laundry done as the credits roll.

And now a word about the haters: I know many, even those on the left, sneer at the mention of his name, but I happen to think Michael Moore is the greatest thing since Rush Limbaugh. Worst you can say about the guy is he’s spent a career trying to kid and cajole a country into recovering its founding principles. I suppose it’s because he always stacks the deck of facts so precariously in his films that the first  reaction of every journalist is to is to try to tip it over. Here I am just minutes after seeing a Tuesday morning screening of SiCKO, listening to some truth-squading NPR reporter call up his mom in Canada to dispute Moore’s claims about Canada’s national health system, which has covered every Canadian citizen since 1961. Moore’s film leaves the impression that there are no long lines or waiting lists North of the Border, but the radio reporter’s mom points out that she has been on a year-long waiting listed for a hip replacement. The reporter signs off, leaving behind the unspoken suspicion that if Moore is wrong about waiting rooms in Canada, what else is he wrong about?

reaction of every journalist is to is to try to tip it over. Here I am just minutes after seeing a Tuesday morning screening of SiCKO, listening to some truth-squading NPR reporter call up his mom in Canada to dispute Moore’s claims about Canada’s national health system, which has covered every Canadian citizen since 1961. Moore’s film leaves the impression that there are no long lines or waiting lists North of the Border, but the radio reporter’s mom points out that she has been on a year-long waiting listed for a hip replacement. The reporter signs off, leaving behind the unspoken suspicion that if Moore is wrong about waiting rooms in Canada, what else is he wrong about?

Curiously, a similar campaign was launched to chip away at the legitimacy of Fahrenheit 9/11, when a vast right wing conspiracy array of talking heads rabidly gnawed at the film’s moorings in truth. They were like gremlins vandalizing Moore’s airborne dirigible, hoping to bring it down before it went Hindenburg all over the 2004 presidential election. By election day, the conventional wisdom was that Fahrenheit 9/11 was just a wacky left-wing conspiracy flick, a piece of a creative fiction intended to embarrass the President in an election year. And yet, Moore had the last laugh. Today, the basic premises of that film — that Bush was asleep at the switch on 9/11 and then exploited the disaster to tighten the reins of power, misused it to drag the country kicking and screaming into the black hole of Iraq and methodically stoked public fears of terrorism to win re-election — are no longer the province of the lunatic fringe (“the Michael Moore wing of the Democratic party”), but rather the conventional wisdom of the Great American Middle. Lord help the health care barons when this thing comes out on DVD and really starts to soak into the blue-lit living rooms of Middle America. If ever there was a populist cause that could turn the country into a angry mob of torch-wielding villagers, it’s access to health care. SiCKO is clean-burning fuel for that fire. Anybody got a light? GRADE A