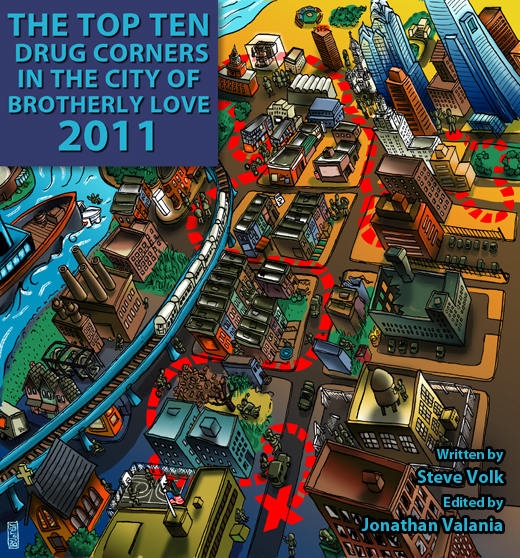

[Illustration by JAY BEVENOUR]

EDITOR’S NOTE: The following report — the product of a partnership between Phawker and PW and funded by a grant from J-Lab and the William Penn Foundation — ranks the city’s 10 worst drug corners the way Philly Mag ranks pizza or bars or bikini wax salons. Sarcasm aside, the story is no joke, rather it is the product of six months of old fashioned shoe leather reporting, arrest statistics crunching, and and dozens of interviews with the police,academics, neighbors, drug dealers and drug buyers. The hope is that we can spark a new conversation about drug policy in a city where vast stretches — block after block, neighborhood upon neighborhood – have been ravaged by an illegal drug trade that impacts everyone directly or indirectly whether they know it or not. Maybe, just maybe, our wishful thinking goes, by yanking the readers out of the comfort zone of their safe and happy lives and dropping them at ground zero of the city’s 10 hottest drug war zones, the beginnings of real change — in perception, in policy, in understanding and empathy — could be enacted. Hopefully, that’s where you come in.

***

In 2007 I wrote a cover story for the Philadelphia Weekly called Top 10 Drug Corners that ranked the city’s most depressing and dangerous drug corners like Philadelphia Magazine ranks pizza or bars or bikini wax salons. After all, when you strip away all the blood and guts and stray gunfire, drug dealing is, at heart, competitive retailing of a rare and precious commodity: Feeling good. There is, of course, a huge market for such a commodity, especially in places that are inhospitable to legitimate business and industry. Which is why the drug trade always seems to flourish in places where angels fear to tread. Philadelphia, one of the poorest major cities in America, has many such places.

In many of the city’s neighborhoods, the opportunities for gainful employment are so scarce and hopelessness so abundant that a vacuum has been created — and nature, of course, abhors a vacuum. With no noise of legitimate enterprise to fill the air — no rumble of a truck engine toting freight, no murmur of conversation from shoppers mingling on the sidewalk — the most prevalent sounds arise from the underground economy.

“Wet, wet, wet.”

“Xannies!”

“Suboxone!”

“Oxy!”

“Greenies!”

“Dope?”

“You smokin’ that crack?”

“What you need?”

Eight different come-ons, from a vast collection of different Philadelphians—white, black and Latin; young, middle-aged and graying. All these offers speak to the same basic truths: Philadelphia is awash in the narcotics trade. And like all illicit economies, the drug trade begets a brutal gangsterism whose stock in trade is violence — violence on an industrial scale. The statistics are as astonishing as they are appalling. “We’ve had 16,000 shootings here in the last 10 years,” says Assistant U.S. Attorney Rob Reed. “Sixteen thousand!” That averages out to four Philadelphians being shot every day, or one citizen every six hours. Since 2008, more Americans have been murdered in Philadelphia than killed in Iraq. In other words, we have the equivalent of an undeclared shooting war raging semi-visibly in the city’s most desolate and depleted neighborhoods. And Philadelphia is hardly the exception to the rule. Rather, depressingly enough, it is the rule.

As a result, the poorest of the poor in Philadelphia are cut off from the most basic aspects of personhood that the rest of us take for granted. They live in constant fear of seemingly random violence, which, sustained year after year, has created an increasingly common mindset — which some would call cynical and others would call realistic — that the powers that be either cannot help them, do not care to help them, or, even worse, somehow profit from their suffering.

“Who do you think lets all these drugs in here?” is a question I have been asked, countless times, when sources in the city’s poorest communities flip the script on me  and start questioning their questioner. There is a profound hopelessness reflected in that query, a conspiratorial worldview that powerful forces have allied against them. It could be easily dismissed if it weren’t so common, and for that matter, understandable. After all, logic would dictate that if somebody, or many somebodies, wasn’t profiting from all this carnage, it would have been stopped a long, long time ago. Ridiculous, right? And yet, how do you explain that the cycle continues day after day, year upon year, with little change: The bullet-riddled hive of corners, blocks and neighborhoods lorded over by teenagers with guns strapped to their hips; the little boys serving as lookouts calling out ‘5-0,’ warning dope-slingers off the streets when the cops show up, the never-ending line of zombie-fied addicts shuffling up to the dope merchants dispensing their daily fix at pretty much the exact same spots, every day?

and start questioning their questioner. There is a profound hopelessness reflected in that query, a conspiratorial worldview that powerful forces have allied against them. It could be easily dismissed if it weren’t so common, and for that matter, understandable. After all, logic would dictate that if somebody, or many somebodies, wasn’t profiting from all this carnage, it would have been stopped a long, long time ago. Ridiculous, right? And yet, how do you explain that the cycle continues day after day, year upon year, with little change: The bullet-riddled hive of corners, blocks and neighborhoods lorded over by teenagers with guns strapped to their hips; the little boys serving as lookouts calling out ‘5-0,’ warning dope-slingers off the streets when the cops show up, the never-ending line of zombie-fied addicts shuffling up to the dope merchants dispensing their daily fix at pretty much the exact same spots, every day?

What doesn’t enter into the equation, for the conspiracy-minded, is that the neglect they experience all around them might be a product of public and institutional ignorance. For most people who live and work in Center City Philadelphia, drug-dealing and all its attendant violence, destruction and misery is the stuff of television programs like The Wire whereas here, in North Philly, they are living it. “I don’t think the rest of us really understand what it’s like to live in these more violent communities,” says Reed, the U.S. Attorney. “Because I think, if we did, there would be a greater sense of outrage than there is.”

That is, in a nutshell, the reason for this article. Maybe, just maybe, our wishful thinking goes, by yanking the readers out of the comfort zone of their complacency and dropping them at ground zero of the city’s 10 hottest drug war zones, the beginnings of real change — in perception, in policy, in understanding and empathy — could be enacted.

The reaction to Top 10 Drug Corners in Philadelphia 2007 was overwhelming, triggering a number of intended and unintended consequences. Real estate agents complained that certain neighborhoods, which they invariably had a financial stake in, were unfairly targeted while drug users expressed gratitude for providing a convenient road map for copping. At the same time, citizen activists expressed gratitude that a media outlet devoted so much space and reporting man-hours to document the ever-expanding depths of the city’s drug problem. The result was one of the most widely read articles in the paper’s history.

As such, Top 10 Drug Corners Of Philadelphia 2011 arrives with some major caveats: First, there is so much drug dealing in the city — and the mechanics and geography of the drug trade is so fluid — that narrowing it down to the top 10 corners is a fool’s errand: It could well be 20 corners, or 50 or 100. Furthermore, even the most extensive combination of face-to-face interviews, boots-on-the-ground surveillance and crunching of arrest stats will at best result in a snapshot of a moment in time, and the enduring accuracy of that resulting picture is debatable. The truth is that the locus of the most heavily-trafficked drugs corners is constantly shifting in reaction to supply and demand, police activity and internecine turf warfare. If one corner is not active at the moment, then the action most likely lurks around the next corner or will be heading this way awfully soon.

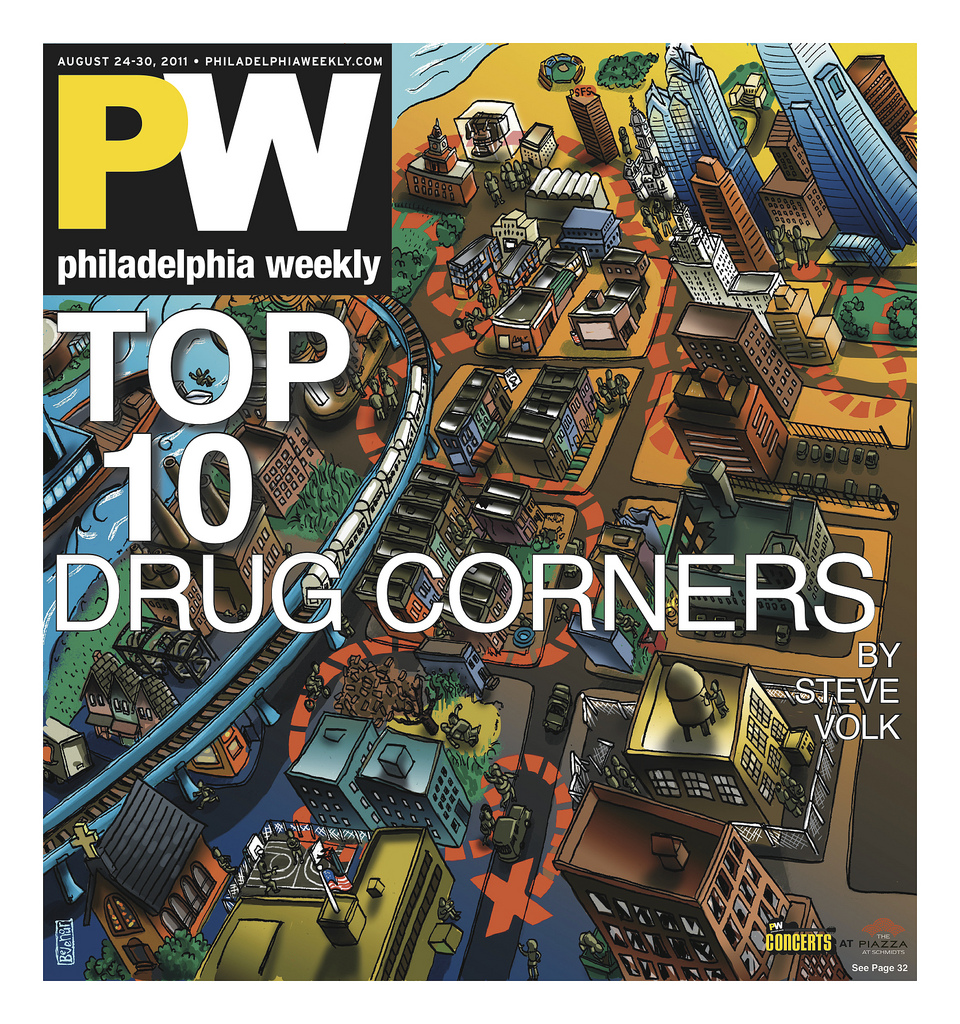

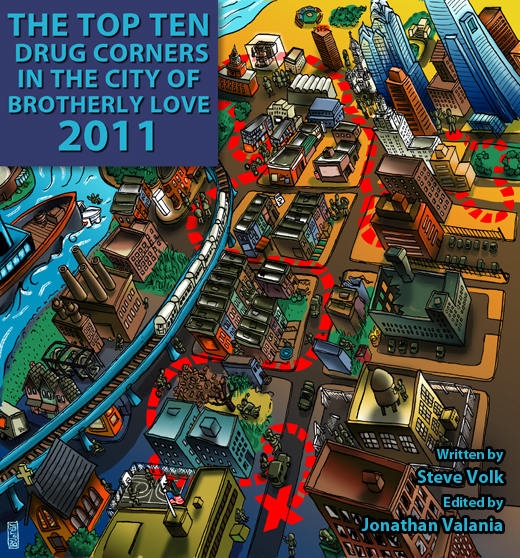

Most will sensibly interpret this as a list of corners to stay away from. Others will, ill-advisedly, use it as a buyer’s guide. And for that reason, this time around, there are  far fewer references to what specific drugs are available at these different spots. Unlike the list published in 2007, this one corresponds, almost entirely, with police statistics. In fact, nine of the top 10 corners on our list correspond with the corners where police conducted the most drug arrests over the past couple of years. Some changes were made in the ordering of these corners, based on first-hand observations. The point of this list is not that all of Philadelphia is consumed by the illicit drug trade, but rather that one particular part of Philadelphia (and a relatively small one at that) suffers the lion’s share of its ravages: All 10 drug corners on our list are located in North Philadelphia’s Kensington and Fairhill sections.

far fewer references to what specific drugs are available at these different spots. Unlike the list published in 2007, this one corresponds, almost entirely, with police statistics. In fact, nine of the top 10 corners on our list correspond with the corners where police conducted the most drug arrests over the past couple of years. Some changes were made in the ordering of these corners, based on first-hand observations. The point of this list is not that all of Philadelphia is consumed by the illicit drug trade, but rather that one particular part of Philadelphia (and a relatively small one at that) suffers the lion’s share of its ravages: All 10 drug corners on our list are located in North Philadelphia’s Kensington and Fairhill sections.

Which is not to say that no one is fighting the good fight there. Neighborhood activists are always in play. And judging by the numbers, the police have focused their attention on this area of the city. In fact, a map of the city’s corners where five drug-related arrests or more were made for the 15 months from 2010 to the end of March 2011, demonstrates that no other region of the city is the scene of so many narcotics busts as the real estate stretching from Lehigh Avenue to Westmoreland, and from Kensington Avenue to Broad Street. But in fact, within that section of the city, the majority of arrests were concentrated in an even smaller area — from Lehigh to the south to Westmoreland, roughly a half-mile stretch, and from Kensington Avenue to N. Fifth Street, a distance just less than a mile.

Starting back in late March and continuing up until a week ago, I did a lot of shoe-leather reporting. I walked through the dodgiest sections of West Philadelphia, South Philadelphia and South- and Northwest Philadelphia. There were many areas I was glad to walk away from. But no area of the city came close to Kensington and Fairhill in terms of the density and brazenness of the drug selling. And for that reason, all 10 of our corners sit in this same blighted, godforsaken pocket, and what we find there begs the question: Is it really true that as a society we are incapable of ending the cycle of poverty, violence and drug dealing that is concentrated in such tiny a section of Philadelphia?

Right now, the answer seems to be yes.

Or, at least, the efforts we’ve undertaken this far simply haven’t worked. In a city with an already overcrowded prison system, the police are working harder here on a purely statistical level than anywhere else. But a simple walk through the neighborhood reveals how little good that has done. These streets are veritable rivers of trash and graffiti, suggesting both City Hall and its residents have given up on even the idea of maintaining appearances. In summer, the stifling heat, the lack of job-generating businesses, the shuttered factory buildings, and the kids slinking this way and that, hustling dope and invariably strapped with guns, coalesce into a vast, depressing mosaic of hopelessness and despair in a city where 25 percent live under the poverty line and more than half read at a sixth-grade level or below.

In the face of all this blighted urban dysfunction, the list of viable remedies is short: We could remount something like Operation Safe Streets, making police so visible in the neighborhood that drug dealers simply cannot operate as they do now—out in the open in broad daylight. But the cost of that program was around $4 million a month in police overtime and ultimately deemed unsustainable. Even though an argument could be made that Safe Streets was worth every dime, the city no longer has the political will or financial resources to maintain what was essentially a police occupation of wide swaths of the city.

Perhaps the saddest aspect of the streets I walked in North Philadelphia is that the people risking their lives to either sell, take or, often sell and take drugs, are  carrying out these deeds quite literally in the shadows of the old factory buildings that once upon a time employed thousands of hardworking Philadelphians who actually made things.

carrying out these deeds quite literally in the shadows of the old factory buildings that once upon a time employed thousands of hardworking Philadelphians who actually made things.

Until the 1960s, Philadelphia was a crucial pillar of the American manufacturing base. North Philadelphia was a working class enclave. The many thousands of rowhomes both east and west of Broad Street were built to serve this population of workers; and the Broad Street Line subway was built in the 1920s to move passengers from the northern part of the city to City Hall quickly and conveniently. The academic study, Workshop of the World, by Phillip Scranton, captures the vibrant money-making wharp and woof of mid-20th century Philadelphia:

“[Workers] churned out laces, socks, carpets, blankets, rope and cordage, men’s suitings and women’s dress goods, silk stockings, upholstery, tapestries, braids, bindings, ribbons, coverlets, knit fabric and sweaters, surgical fabrics, military cloths and trimmings, draperies, and yarns… Carpet makers purchased yarn from one firm, had it dyed at a second, bought pattern designs from a third, punched cards to control the weaving process from a fourth. The card makers got coated paper stock from specialist paper manufacturers in Manayunk; the dyers bought special machinery from Procter and Schwartz which in turn purchased metal castings from various city foundries.”

But today these good jobs fit for workers without college educations are long gone; and too many residents use that North Philly subway line not to attain marriage licenses and construction permits, nor to engage in the legitimate commerce of Center City, but to make it on time — or not — for court dates at the Criminal Justice Center. Solving the drug problem by purely economic means would require a level of public and private investment on a scale that is simply not tenable in this day and age. Barring some massive New Deal-style public works initiative that revives the manufacturing base of the United States, the prospect of employing our way out of this problem seems remote at best. So finally, this leaves us with our last and perhaps most intriguing, promising and politically hazardous possibility.

We could legalize drugs.

That is itself the topic for another great many articles, and we will take no position on it here, except to say that if we legalized narcotics tomorrow surely the violent young men slinging dope on the corners of North Philadelphia would be rendered as obsolete as bootleggers after prohibition. But until then, we give you, for better or for worse, the Top 10 Drug Corners in the City Of Brotherly Love circa 2011.

10. 100 E. Somerset Street

Sitting just a block or so from the infamous B Street bridge, this corner is part of the de facto junkie superhighway that connects all the car, train and foot traffic on Kensington Avenue to the wide range of drug corners in the area. I witnessed several hand-to-hand transactions here between a small group of teens on the block and junkies ambling through. This thoroughfare, bordered by warehouses, seems to act primarily as a byway for users on the way to their next fix. That is why I actually downgraded it to 10, though it ranks 7th in the sheer number of arrests with 50.

I stood here and watched one young man and a woman, who could have been his mother, traveling back from a score toward the train that would whisk them away from all this urban decay. The woman ambled, legs wide, as if she had climbed down from a massive horse. This unsteady gait was the first thing to draw attention. But then, still walking, she reached deep down into her baggy sweat pants and started fishing around in there. The young man looked more scared than embarrassed. The older woman’s behavior wasn’t just mortifying. It was the sort of thing that could get them searched and arrested.

“What the fuck are you doing?” he hissed.

He was dressed in long, baggy shorts and a plain white t-shirt on a hot day, with a ballcap he twisted furiously in his anxious, angry hands. The woman said nothing.  She just kept prying around, her right arm buried up to the elbow in her pants. This went on for several long seconds, which passed with agonizing slowness. The young man began walking just inches in front of his female companion to block any view of her. This struck me as entirely unnecessary. Except for a couple of warehouses here, the street is bordered by numerous empty, city-owned lots, offering anonymity and plenty of wide open space in which to nod off. But the man seemed unaware of how safe he was scoring product here.

She just kept prying around, her right arm buried up to the elbow in her pants. This went on for several long seconds, which passed with agonizing slowness. The young man began walking just inches in front of his female companion to block any view of her. This struck me as entirely unnecessary. Except for a couple of warehouses here, the street is bordered by numerous empty, city-owned lots, offering anonymity and plenty of wide open space in which to nod off. But the man seemed unaware of how safe he was scoring product here.

“What the fuck?” he said, raising his voice.

After several long seconds of this, which felt like minutes, the man stopped and turned to her. “What the fuck?” he said. His companion was a heavyset thing, middle-aged, with big, sad, swollen eyes. And even before this she looked to be on the verge of crying. She stopped. And with a hurt look in her eyes, she used both hands to pull the front of her pants out several inches from her waist. Then she peered down into her crotch like there might be something written there and drove one unsteady hand into her waistband. Her hand shaking, she yanked out a big, plastic baggie. If anyone had any doubts before, they were gone now. They were junkies, Laurel and Hardying their way through life.

“I gotta fix it,” she said.

She extended the hand holding the bag back into her pants and wiggled it around for a moment, as if she was adjusting a maxi pad. Satisfied, she let her pants snap back snug around her waist. The young man with her glared angrily. But now she looked happy. She hopped up and down on her heels, giving the drugs a good shake in her crotch to make sure they would not shift around in her pants. Then she grinned at him and even turned toward me, smiling broadly and offering a gee-whiz shrug. And why not? This being the life she had chosen, how could she complain when sometimes the indignity of it all swelled up for everyone to see?

9. 2900 N. 3rd Street

And when this corner was up and running, the crew there seemed particularly disciplined. One teenager looked away from me and announced “Cop, cop, cop,” as I walked by. The rest just averted their eyes entirely. At other corners, they just glared at me and went right on working. But beyond that, the method of operation seemed common: Some kids act as lookouts; one man collects money; another dispenses product. The extra bodies could be hangers on. But some of them, at least, are likely there to help re-up the supplies when they run low. Others might act as decoys if the cops were to make a bust here. Decoys, if they are doing it right, lure the cops away by running in a different direction than the people actually carrying evidence.

Located off the corner of Third and Cambria, and only a block from the infamous Third and Indiana, around which former Inquirer columnist Steve Lopez built a harrowing novel, this strip was not always active. But over the 15-month time period leading up to my first visit there this spring, this street accounted for 38 arrests. Nearby Third and Indiana accounted for another 22.

The street here is lined with workman’s vans and family cars. Counting boarded up windows, the vacancy rate seems to be something less than 20 percent — bad, but not so bad as many of the blocks on this list. The house exteriors are clean enough. And there is less trash and debris than most of the corners in the neighborhood. But there is undoubtedly far more money passing through the corner than passes through these houses on a good week. The most expensive house here sold for just $40,000 in 2010 and the median income, at the last census, was less than $12,000. Potter Thomas, the area elementary school, is failing miserably, according to the Pennsylvania State Assessment Tests. Less than 10 percent of the kids score at proficiency level in math in the 8th grade, and just 21.6 percent reach proficiency in reading.

8. 2800 Hope Street

Perhaps the most ironically named street in Philadelphia, Hope Street seemed far more active to me than the statistics might have suggested. With just 28 arrests, Hope is actually ranked 27th in the total number of drug arrests (it is the only corner in our top 10 not actually among the top 10 for arrests). But every time I came through here Hope was up and running, and Hope is where I first began to figure out how product moves in these parts.

Just a short walk from the drug bazaar at Kensington and Somerset, Hope is a little side street that periodically blinks out and reappears again as Philly stretches northward. I only got here after I tailed users who got off the El at Kensington and Somerset. Twice, on hot mornings in early May, I followed small groups of junkies as they made their way off Kensington Avenue and into the bowels of North Philadelphia.

As one user told me, venturing into the wrong area at the wrong moment with the wrong look on your face will get a man “kilt or at least an ass whupping.” So I followed the skinny, white boys with translucent skin, blinking in the sunlight like noctural animals as they came shuffling off Kensington Avenue; and I followed the hipster kids, venturing away from the legit businesses on the Ave. to live out their own Trainspotting moment. In the end, the only thing separating the long gone junkies from the hipsters appeared to be age. Both dressed in skinny jeans and t-shirts. Both wore Converse sneakers. But the junkies were skinnier, with big gaps in their smiles. They were all going back, most likely, to far better streets than Hope, which seemingly exists only to serve the habits of people with more money than the  residents here, where the nicest house on the block sells for just $8,600. And I felt safe in their company, thinking drug dealers are unlikely to beat up their own customers. But Narcotics Captain Deborah Frazier says others in the neighborhoods see them as easy prey. “A lot of these suburban kids get jumped,” he says. “Think about it. Everyone knows what they are there for and that they are walking around with money in their hand.”

residents here, where the nicest house on the block sells for just $8,600. And I felt safe in their company, thinking drug dealers are unlikely to beat up their own customers. But Narcotics Captain Deborah Frazier says others in the neighborhoods see them as easy prey. “A lot of these suburban kids get jumped,” he says. “Think about it. Everyone knows what they are there for and that they are walking around with money in their hand.”

Both groups, the lifers and the hipster tourists, wound up on Hope, doing quick hand-to-hands within a big spit’s distance of a crossing guard on Front Street. “I got no problems with the dealers,” the guard told me. “I mean, I gotta problem with what they doing but I tell ‘em I need this block clear for a couple of hours, they get out the way. They know it’d be bad for business to fight it.”

The guard, by the way, is there to assist children on their way to Sheppard Isaac School, a K-4 institution, currently earning the lowest possible score on the Great Schools scale, a 1 out of a possible 10. Hope, it turned out, was where the hot dope of the day — Adidas — was being sold one blazing hot day this past May. And during the three or four hours I was in the neighborhood, the traffic never really slowed. I holed up for a while, in fact, on the B Street bridge, near Tusculum, and watched as a steady stream of customers paraded past. With each train, every 10 minutes or so, a new group shuffled toward Hope: three on one train, seven on another, four on the next, two on the one after that; a staggering 15 passed by me after one train barreled into the station around nine in the morning. In two hours I watched nearly five dozen customers stream past me and there’s no telling how many got off the train and traveled other routes to other corners to buy a strain of heroin other than Adidas.

7. 200 E. Stella Street

The most active corners seem to enjoy the same amenities as any shopping center, such as proximity to main driving thoroughfares and public transportation as well as the natural boosts in foot traffic generated by bodegas or Chinese takeouts. But between Indiana and Clearfield sits an obscure little side street that functions as a drug corner primarily because of its isolation. With a spotter at the east and west ends of the street, any outfit can be alerted to the police way before they drive up. Every time I crossed this street myself, in fact, I felt like a trespasser. Heads cocked up and down the block to see me. A couple of times I saw the telltale lines — four, five, or six people deep — shuffling from one young dealer to the next, hand extended. One takes your money. The next gives you the prize.

I walked alongside a heavy user here, an old African-American man who hesitated a long time when I asked for his name. “Eh,” he finally sighed. “Hoppy.” He dressed in jeans and a big, buttondown flannel shirt on a hot day. His clothes were covered in a thick layer of grime. He vowed to show me all the spots. But when we got west of Front, he said he needed to break off. “What’s up?” I asked, thinking he wanted money. “Them d-boys,” he said. “They be smoking that wet.”

I’d heard a lot about this: drug dealers smoking weed laced with PCP. A lot of people think they are a big source of violence in the neighborhoods, dealers getting high on product that’s more hardcore than most of their supplies. “How do you know they’re on wet?” I asked him. “’Cause they be crazy,” he said. “Just look in their eyes. They be looking at you but they seeing something else.”

5. & 6. 3300 Argyle Street & 3000 N. Water Street

With a stunning 60-plus arrests in each of these two blocks over a 15-month time period, I expected these blocks to be silent — policed into quietude. Those numbers are high for streets with this many outward signs of the stability that would render dealing unlikely: lots of families, and some working man’s vans and trucks along the sidewalk signalling that most people here are eking out a living legitimately. Both streets were quiet on several visits, but another time I saw a line of users stacked five and six deep. “Heroin is a morning market,” says Narcotics Capt. Deborah Frazier. “With crack, addicts will smoke a rock and come back for more. But heroin users, they nod off and drool and they want to be someplace safe for the day with all the heroin they need. So they come out in the morning and buy as much as they need and take it home or wherever they’re going.”

Frazier looked up the arrest statistics for this year on Argyle and N. Water, and they do seem to be running significantly behind last year’s pace. Does that mean these corners are less active or the police are simply making fewer arrests there? Does it matter? Are arrests really the right metric for measuring success? There are  dozens of corners on which dealers can (and do) operate and as soon as one gets arrested, without fail another steps up to take his place. As one of the junkies around here told me, “Every crew keeps a list. Someone get arrested they just go to the next man on the list. Now he gets his shot.”

dozens of corners on which dealers can (and do) operate and as soon as one gets arrested, without fail another steps up to take his place. As one of the junkies around here told me, “Every crew keeps a list. Someone get arrested they just go to the next man on the list. Now he gets his shot.”

Argyle is paired with N. Water because both streets were so similar, statistically, and among the most frightening I walked — not because they were always up (they weren’t) but because each time I went I had no idea what to expect. At least, in the heavily trafficked and frequently busy drug markets crowding Kensington and Somerset, I knew what was coming. But on Argyle and Water I never knew what I’d find — a residential block, or a squad doing business.

“I wouldn’t blame anyone for being scared of North Water,” says 24th district police Capt. Thomas Davidson. “I had one of my officers shot there last summer.” In that incident, police pulled over a white van suspected of involvement in a shooting earlier in the day. They were right. Two gunmen got out of the car in the 3000 block of N. Water and started firing, ditching a total of eight guns on the block as they fled. Police Officer Kevin Livewell was hit in the leg. Police recovered loaded handguns and assault rifles too powerful to be stopped by police body armor. “Those blocks, Water and Argyle, are very isolated,” adds Davidson. “Once you’re on them, there’s nowhere to go.”

4. 5th & Westmoreland Street/3300 N. 5th Street

She’d like to help, she just can’t, she tells me. She is a petite woman, in late middle-age. She has decorated the fenced in lot next to her home with a menagerie of stone carvings. She tends to her bushes, flowers and trees with the care of someone who loves her home and wants it to be as beautiful as she can make it, not only for herself, but for the people who pass by. But this neighborhood doesn’t seem to care. Or, to be fair, the young boys across the street, rolling in and out of the little no-name bar there like the tide—they don’t care.

They don’t care about her property. They don’t care about her dignity. They don’t care about her right to have a conversation with whomever she pleases, including a stranger with a notebook and pen in his hands. Less than a minute after I called to her, less than a minute after she reluctantly pressed her nose up to the steel mesh fence between us, we had company. I had glanced back across the street toward the bar, its door wide open, people parading in and out. Maybe that was my mistake. ‘Cause one dude caught my eye, smacked a bigger dude on the shoulder and nodded in my direction. And suddenly, this poor old woman, who got as far as telling me her block is a tough place to live, was intimidated into silence by the sudden presence of a big young bull of a kid—I’m guessing 20 years old, six-foot-three and an easy 220 pounds.

This was my third trip to this little two-block stretch of Fifth and Westmoreland Streets and the abutting 3300 block of N. Fifth Street. These blocks were among the  most active I saw this year, and the stats demonstrate that with 21 arrests on Fifth and Westmoreland and 59 on the 3300 block of N. Fifth Street.

most active I saw this year, and the stats demonstrate that with 21 arrests on Fifth and Westmoreland and 59 on the 3300 block of N. Fifth Street.

Economically, things are just as grim. The average sale price of a home here tops out at $10,000. And in terms of drug activity, one perch or another along this stretch always seemed to be up, with teenagers and 20-somethings wearing those ubiquitous white-t uniforms working to feed this city’s bottomless hunger for dope. Those young ones, they own these streets. So the young man who came over to monitor my conversation with one of his neighbors didn’t introduce himself. He sent a message by standing close enough to reach one big hand out and choke me if he wished. “Hey,” I said, offering an easy smile.

He said nothing. He did not smile in return. Just stared back at me with no affect at all. He was here to intimidate, and it was working. The woman started to back away from the fence, making low guttural noises, her nerve failing her. I can’t imagine what that is like _ to be an elder on the block and know that the young men on the street are in charge; to suffer the indignity of knowing this kid will show you no respect and there is nothing you can reasonably do about it. But I also figured if she left the conversation now she would only make things worse. The guy would figure she was talking about something she shouldn’t have been — like the crack, weed and heroin being dealt around these parts. So I improvised.

“I can see you’re busy,” I said, motioning toward all the gardening tools lying around inside her fence line. “But if you’d just take one more minute to tell me about the work you’ve been doing here…” She paused. The muscle wrinkled his eyebrows. And I forged ahead through many long minutes of total bullshit: I asked her about the sculptures in her garden and whether she had made them; the number of years she’d lived in the community and her motivations in working so hard to shape this little garden she tended to. Still, the young man would simply not go away. So I started talking about a tragic little mess of an “art installation” that stood right next to us on the street—a stack of plastic coke bottles and plastic milk crates formed into a primitive robot, with pointed limbs and bottlecap eyes.

“You do this with neighborhood kids?” I asked. The woman still looked nervous. But she kept answering my questions and I dutifully took notes. I glanced over again at the big guy next to me and saw his attention flagging. He looked at the sidewalk and leaned against the fence, his eyes glazing over. But still, he would not go away. So I kept going for a few minutes more till finally he said: “Who you, man?”

“A reporter,” I told him. “I noticed the artwork here,” I said, “and wanted to do a little story on it.” He chuckled. He had a warm, easy smile. Then he walked back across the street. When he left, the woman thanked me and retreated back into the depths of her yard, to whatever life she has carved out for herself in the shade and darkness behind her big metal fence.

3. 2800 N. Mutter Street

Mutter is a vital strip in a tangle of nearby streets that includes Palethorp, Mascher and Waterloo, all connected by Somerset. I witnessed numerous stacks of people shuffled one behind the other for drugs like they were waiting in line at the post office.

This is also the first place I saw one of the dealers glance at me with that faraway look — like he was staring at and through me at the same time, eyes wide. Westmoreland and Rorer has been documented as the spot in the Badlands to cop “wet” (Seventh and Clearfield is another one I heard mentioned). But the ghosts around here were hollering “wet” one day this June. I say ghosts because teens, most likely gun-strapped and definitely working, seemed to melt in and out of the block from easements and cross streets.

I was never sure precisely where I would find someone operating. But the day I heard someone cry “wet” I quickly recalled all I’d heard and read about the drug. Longtime Phawker contributor Jeff Deeney had chronicled the drug’s dramatic, sometimes psychotic effects for the Daily Beast in April. And by this time, several junkies had warned me that the dealers themselves were often high and extremely unpredictable. “They shoot you for no reason ‘cause they paranoid” one old head told me.

The kid crying wet was covered in a film of sweat, either from the mid-80s heat, or as one of the telltale signs of PCP use. I didn’t know. But I didn’t linger. This one block has been the site of 91 drug arrests in 15 months, with no discernible effect. This block was also the site of three aggravated assaults in June. And 2800 N. Mutter is also among the poorest streets, with homes selling for under $10,000 and an average median income of $11,900.

2. 2700 N. Front Street

Front and nearby Silver Street were big destination points for people getting off the train at Kensington and Somerset in trips I made here throughout May and June. The hand to hands here are quick, with customers giving cash to one man and moving on to another who slips them a baggie. One day, a user came sailing past me, around the corner on to Silver, and briefly holding his arms out to his sides like a human airplane. “Got that Superman today,” he grinned, calling out the name of the day’s hot heroin brand. I asked one man, who appeared to have no part in the drug trade, if he was nervous being so near all this. At first, he shakes his head “no” at me. But he won’t speak or even meet my gaze. Then, as I walk away I hear him call out behind me: “Nah man, they got this down to a science!”

Maybe, but something has shifted in recent years. Here, too, a lot of the dealers themselves look glassy-eyed — like they’re all smoked up on weed, or worse. “Kids who are dealing now don’t do it the way we did it,” says Shawn “Frogg” Banks, a former North Philadelphia drug dealer. “They do get high off their own supplies. They be out there on different drugs themselves.” Banks has been working as a community activist for many years now, interacting with the same kids I spent the spring and early summer watching work the city’s corners. “A lot of them get habits, too.”

1. Kensington and Somerset Streets

All of Philadelphia was fixated on this block last fall when the so-called Kensington Strangler murdered three women in the area and assaulted three others. The killer was arrested and confessed in January. And the whole affair seemed to spark a new level of interest in just what’s happened to Kensington. The Inquirer and Daily News both filed a series of articles describing the nefarious goings on that color life here on the best of days. And even in the wake of the killer’s apprehension it seemed that maybe Philadelphia was about to engage in a giant civic re-think of its most notorious strip. But that hasn’t happened, and there are no outward signs that it will any time soon.

“Xannies,” a man says to me, as soon as I step off the stairs leading down from the platform at Kensington and Somerset. I shake my head no. “Suboxone,” he says,  his voice low. Suboxone is a medication recovering addicts receive in treatment, to help wean their bodies off dependence on heroin or Oxycontin. Sometimes, however, addicts lacking the necessary funds for “H” secure suboxone instead—avoiding withdrawal while they pull together the money for a high. I don’t even respond to this come-on, I am to busy trying to get myself oriented. The amount of people swirling around here, on a sunny day in early June, is absolutely incredible, as it was during another half-dozen trips here.

his voice low. Suboxone is a medication recovering addicts receive in treatment, to help wean their bodies off dependence on heroin or Oxycontin. Sometimes, however, addicts lacking the necessary funds for “H” secure suboxone instead—avoiding withdrawal while they pull together the money for a high. I don’t even respond to this come-on, I am to busy trying to get myself oriented. The amount of people swirling around here, on a sunny day in early June, is absolutely incredible, as it was during another half-dozen trips here.

Hipster kids and full-blown toothless junkies mingle together on the sidewalk. More fit, predatory figures walk among them, directing traffic. “Oxys,” he offers. I shake my head no. “Works,” he says, meaning clean needles. “Weed. Greenies.” Greenies, I know, means speed — or amphetamines. I shake my head no again and the guy steps up real close to me. He is a young African-American male.

“Dope?” he asks. “What you need?”

“I’m all squared away,” I tell him.

His use of the word “need” rather than “want” is so freighted with the submission of addiction.

“A’ight,” he says, and walks away.

Back in March, I spoke to an academic named Phillipe Bourgois, who bought a house in the area and watches the drug trade from his rooftop several days a week. He knows many of the players around here and told me straight out he wished I would draw no attention to this particular corner, because the primary product is “works,” which is street parlance for clean needles. In his estimation, therefore, what goes on here isn’t a — or the — problem. But law enforcement feels differently, regularly making arrests on the strip. And their perspective is easy to understand. Men and women shamble off the train here, all day and all night, and get directions to the drug of their choice. To add to the zoo-like character of the place, the guys telling users where to cop are often users themselves. A big part of the foot traffic includes guys like “Brad,” a junkie I met who boasted he works the corner “seven days a week, seven to seven.” I saw him every time I went to the corner of Kensington and Somerset, though I’m not sure if he remembered me after the first visit. He was drooling that day, nodding even as he spoke, his eyes closed half way, the thick spittle on his lips running slowly down his chin. “I work here,” he told me. “I tell them where the good dope is for $5.”

“What’s good today?” I ask him.

“Adidas is…the bomb…today,” he says, spittle dripping thickly from his lower lip. “It is very, very potent.”

“So you make $5 for referrals?” I ask.

“The customer gives me $5 for the info on what’s hot. If they need me to show ‘em the way to it, I’ll walk ‘em to get their shit for $5 more. And some people, if they can’t poke themselves, I poke ‘em.”

“You inject them?” I ask.

“Yeah,” he said, “and that’s another $5.”

Brad is an extreme example, but he represents a dynamic Dr. David Festinger, a director at The Treatment Research institute, says we need to begin understanding. “People look at a typical drug transaction and see a user and a seller,” he says. “There’s the man supplying the drug and the person who will consume it. But the fact is, much of the time, the person doing the selling is also feeding a habit—perhaps not for that drug, but for some other drug.”

The Treatment Research Institute, where Festinger works, was co-founded in 1992 by A. Thomas McLellan, who worked briefly with the Obama White House to  develop a new national drug policy. His efforts toward reform, toward treating drug use less as a crime than a disease, are thought to have been too liberal for the current administration. And in Festinger’s description of drug dealing, it’s easy to see why. He is asking us to rethink the hand-to-hand transaction: The most liberal among us might already be comfortable saying that both people involved in the exchange need help. But it turns out the dealer often needs more than social and economic help, more than a better education, a job, and improved decision-making skills. In many cases, the dealer, just like the user, needs drug treatment.

develop a new national drug policy. His efforts toward reform, toward treating drug use less as a crime than a disease, are thought to have been too liberal for the current administration. And in Festinger’s description of drug dealing, it’s easy to see why. He is asking us to rethink the hand-to-hand transaction: The most liberal among us might already be comfortable saying that both people involved in the exchange need help. But it turns out the dealer often needs more than social and economic help, more than a better education, a job, and improved decision-making skills. In many cases, the dealer, just like the user, needs drug treatment.

Narcotics Capt. Deborah Frazier says that, in her experience, the number of dealers in North Philly smoking wet — pot laced with PCP — is very, very much in the minority. But they virtually all smoke weed. “For them it’s a culture,” she says. “They roll out of bed, smoke a blunt, play video games, sling on the corner and go buy new gear.”

***

“You’re free to make your drops, collect what need collectin’, won’t nobody bother you, you got my word on it… .”

That line of dialogue, from a police official to a small squadron of drug dealers, is quoted from the acclaimed HBO series, The Wire. The cops, for those who have never seen the show, have designated an uninhabited section of Baltimore as a no-arrest zone where drug dealers will be free to ply their trade unmolested by law enforcement. The drug trade is inevitable, goes the thinking, but if you isolate and monitor it, you reduce the harms incurred in a way that trying to arrest our way out of the problem demonstrably does not. A similar experiment has been carried out in Philadelphia with the tacit approval of mayors and police chiefs for more than four decades — although no mayor or police chief, when pressed, would ever admit to it.

The drug trade seems perfectly legal at the corner of Kensington and Somerset. It’s not quite a no-arrest zone — there have been more than 100 drug arrests within a few block radius. And yet on the days I visited, dozens of dealers, buyers and hype-men—guys like Brad, who serve as walking, drooling advertisements for the day’s most potent products—worked 24-7 with no problem from law enforcement whatsoever.

“This is hell,” one man told me, who works at a repair shop at the corner of Kensington and Somerset. “This is the most godawful place on Earth.” The dealers and their customers, of course, don’t agree. One user told me with evident pride, throwing his shoulders back and surveying the panoply of guys slinging product and people buying it up: “Ain’t nothin’ else like this in the whole fucking U-S-A! Other places they sell heroin. But ain’t no other place where they gon’ take you from the corner, right off the train, and show you where to find it!”

The notorious Kensington Strip extends from the corner of Somerset, where the dealers operate, to Allegheny Avenue, where the prostitutes work what they call “The Stroll.” While hustling for customers, the prostitutes stay far enough away from Somerset to evade any of the gunplay or occasional arrests that go down there. But when they are finished working they often walk the half mile or so to the heroin dealers and cop. This strip of illicit commerce makes a mockery of Kensington’s bygone days as one of the city’s most flourishing manufacturing and retail hubs. As local historian Ken Milano has noted about the neighborhood’s old manufacturing glory days, “There used to be a saying: ‘If you can’t get it at K&A, you can’t get it.’” Unfortunately, that’s still true. It’s just that the merchandise has changed.

***

MY LIFE ON A DRUG CORNER

By Steve Volk

I met my future wife for our second date the day she put in a bid for a house. She was over the top excited — a condition, I would discover, that struck her all the time. She retains the capacity to turn into an 8-year-old girl when sufficiently energized. The sight of a cat can flip the switch. So did our wedding. The disparity in size between the two events makes little difference to her. And over time, I have come to see this aspect of her personality as a blessing. But on that second date, when she told me she had just pulled the trigger on a house in the far reaches of the Graduate Hospital area, I found her level of enthusiasm to be a big problem.

The year was 2005. And I had, by this point, been actively covering drug dealing in Philadelphia for about three years. I had written about the infamous Carpenter Street corridor, which was literally just over the back fence from the house my future wife was targeting. Just weeks before, I had written about a young family — new parents, infant baby — who bought a house in the 2000 block of Kimball Street. They had lived to regret it. Their neighbors in the non-rehabbed homes didn’t much like them. Some had even taken to threatening them.

“What did we do?” the young wife turned to me and asked at one point.

I had no idea what to tell her. But as I sat down to a second-date drink with Lisa, I thought I could do her a solid right out of the gate. I figured I would impress her with what I knew of the neighborhood and maybe save her a bit of heartache in the process. So I told her about Carpenter Street’s history, about the incidents that continued to happen in the area, and about the experience of the couple on nearby Kimball Street. “I don’t know your new street, specifically,” I told her. “But I’d like to take a look at it because it’s near some trouble spots. You might be better off waiting a few years to buy.”

If I remember correctly, she laughed.

She loved the house. She loved the patio in the back. She knew she wanted it the second she walked inside. She had put her bid in and wanted very much for it to be accepted. In short, the neighborhood looked fine to her; and sure, I could go look it over; but nothing I would see or say would change her mind. She was gonna buy the house. I found her to be woefully naïve. But how, precisely, I wound up marrying a woman I found so infuriatingly unrealistic is a different story; and I won’t bore you with that tale here. This is a story about drug dealing. This is a story about watching a neighborhood shift. And it is a story that ends well — not just for me, but for Philadelphia.

***

I did check out the block. The first thing I noticed is what I’d seen in the city’s more violent neighborhoods. Drawn blinds. I checked with some police I knew on the crime stats in the block and they were relatively positive. But they all said they wouldn’t advise their girlfriend to move there — not yet, anyway.

There was no budging Lisa, though. Her bid was accepted. A move-in date was set. I was about to watch some urban pioneering, up close and personal. I moved in with Lisa, in fact, just one year after she bought the house. And though I expected to teach Lisa a thing or two, I myself learned way more than I expected.

For starters, my neighbors were and remain aces. The people here run a tight-knit block. We look out for each other. When someone is away for the week, we know  and keep an eye out. We shovel each other’s walks in the winter. All told, we cover a few generations. But the people generally seem to like one another — from seniors to young marrieds and singles. And in the last six years we saw an awesome amount of change.

and keep an eye out. We shovel each other’s walks in the winter. All told, we cover a few generations. But the people generally seem to like one another — from seniors to young marrieds and singles. And in the last six years we saw an awesome amount of change.

When we got here, our next-door neighbor was in a relationship built on bare knuckles and distrust. A man, woman and three kids lived in the little house. And mostly their disputes stayed indoors. But sometimes the trouble spilled out into the street where everyone could see it. He beat on her. She did her best to beat him back. And when the cops showed up, she defended the man who only seconds before aimed balled-up rights and lefts in her direction.

So, domestic violence?

Check.

Gunfire?

You bet. We heard gunshots on or around our block at every three or four months.

Drug dealing?

Of course.

In fact, two men on the block appeared to be active dealers. And our block was an occasional destination point for neighborhood junkies who lined up as many as five or six deep at a time outside one particular house. The door opened. They stuck a hand inside. They brought that hand back out of the dark, shoved it in a pocket, turned on a heel and left. Sometimes a young dude would show up and stand on the corner, leaning into cars as they passed by. Every so often he would walk back to this particular house for a minute, return to his post and greet more motorists as the traffic increased to surprisingly high levels for our little corridor.

The lead dog, the guy I took to be in charge, was super friendly. I’m not going to name him or ID his house, for reasons that will become obvious later. But for the sake of this story let’s call him “Chuck.” Chuck is probably about 60, I’m thinking, an old head who is always smiling and waving and saying hello like the mayor. The act was transparent. I don’t believe he for one single second is stupid enough to think we didn’t notice the traffic going to and from his house, the skeletal condition of his average visitor, or the hushed conversations he had with the young dudes who seemed to be in his employ. And I don’t believe he thinks, for a single instant, that I don’t see him as a problem. But living in close proximity, the way we do in the row houses around here—well, sometimes appearance creates its own reality. And the appearance of a peaceable relationship is so very much better than the alternative. So, it seemed to me, as long as we could maintain this appearance maybe everything was all right, or at least as all right as it needed to be. But then things got, for one night, anyway, way worse.

***

There was a young buck on the street who seemed to work with Chuck. He never manned a post. But the two were tight. They engaged in lots of quiet conversations. The young dude would pedal on and off the block on his bicycle, stopping into Chuck’s between times.

The young dude knew me, knew that I wrote for Philadelphia Weekly and had sources in the Philly PD.

I liked him. Sometimes we’d stop and have long conversations. And I didn’t let his seeming involvement in the dealing on the block stop me from talking to him. Maybe I was fooling myself on all this. But I took us to have an unspoken understanding. Everything was going to be just fine as long as things were just fine. Whatever was happening, I saw no need to write about it unless some vague line was ever crossed. And then, in 2008, as Lisa and I sat watching television, a burst of gunfire sounded right outside our window.

The booms were so loud and sudden and for the first time in my life I found I had to carry out the same sort of protective measures that dozens of sources in the cities worst neighborhoods had told me they had to learn and carry out on a regular basis just to survive. I kicked the coffee table across the floor and slid down off the couch to the hardwood, taking Lisa with me. Long seconds passed. Footsteps beat outside. We were below the level of our front windows now, after that first pop-pop of gunfire. If a bullet was going to get us now it would have to come in at an odd angle or penetrate all that brick and mortar on the way. My mind was going the whole time. I knew, from talking to neighborhood residents, that what made the most sense was to retreat away from the windows, to some interior portion of the house, to put as many walls as possible between us and the bullets flying outside. And stay low. But time ticked away in the heavy silence that follows a little gunplay, and I started to think that was it. But then a second series of booming gunshots sounded. How many? Four, five, six, more…? All right on our street.

We scurried to the back of the house and didn’t come back to the windows for many minutes, till we saw the rotating police lights flickering in through our windows and extending down the hall we’d raced to get away from danger. It was morning the next day when I saw someone I never saw before, standing on the young dude’s front stoop, in what I intuitively took to be a very important conversation. This guy was maybe five years older than my neighbor, and dressed slick — brand new sneaks, sweet shades propped up on his head, designer jeans. He looked like a business man to me, in the context of the previous night, and I decided to do something that was probably a little foolish. I walked over to my neighbor’s stoop and said, “How about last night?”

“Yeah, man,” he said. The new guy gave me a quick screw face. “What about last night?” he asked. His tone was already hot. But I had learned from Chuck that maintaining appearances creates its own reality, so I said, real evenly, “The gunfire.” I looked straight at the guy when I said it and turned back to my neighbor. “That was nuts, right?” I walked up on to the stoop and shook my neighbor’s hand, and then the stranger’s. He had one eyebrow raised as he took my hand and gripped it.

He was a compact little dude, five-eight, lean. I was pretty clear he could beat my ass. “Yeah, man,” my neighbor said. By now, I’d surveyed the damage. Two  neighbors had bullet holes in their front doors. Two more had bullet holes in their cars. And no gunmen had been seriously hurt. “Last night was dangerous for everybody,” I said. “Anybody could have been hit.” The new guy already had enough of me before I walked up. I knew this. But I was still a little shocked when he seemed so determined to ruin the nice, neighborly appearance I was trying to create: “Why don’t you mind your own business?” he asked. I admit. This got me hot. My first thought was a mix of fear and anger. “The gunfire happened on my block,” I said. “That makes it my business. I mean, I can’t come out here and talk to my neighbor about what happened on our block?”

neighbors had bullet holes in their front doors. Two more had bullet holes in their cars. And no gunmen had been seriously hurt. “Last night was dangerous for everybody,” I said. “Anybody could have been hit.” The new guy already had enough of me before I walked up. I knew this. But I was still a little shocked when he seemed so determined to ruin the nice, neighborly appearance I was trying to create: “Why don’t you mind your own business?” he asked. I admit. This got me hot. My first thought was a mix of fear and anger. “The gunfire happened on my block,” I said. “That makes it my business. I mean, I can’t come out here and talk to my neighbor about what happened on our block?”

The new man looked at me like I was crazy. But I cut a quick glance at my neighbor who was looking at the stranger, squinting and grimacing and shaking his head no. With that little gesture, I felt, rightly or wrongly, like I’d just been given some serious hand. And what I said from there was a mixture of bravado, foolishness and good, common sense. “The neighborhood’s changing,” I said. “Maybe people in other neighborhoods figure they better get out of the way when something is going on. But the people moving here now, we don’t see it that way.”

I looked back at my neighbor. “I’m not stupid,” I said. “I’ve been here for a while and I know there’s shit that goes on. I don’t really care as long as it doesn’t endanger me or anyone else here. But last night? That shit can’t happen. Anyone could have been hit by that. I could have been hit. My girlfriend could have been hit.” I turned back to the new guy, who was looking at me stone-faced but not saying anything. And this is where I started getting really stupid. I smiled. “Isn’t it funny?” I asked. “These guys, they’re all about being gangsters. But the mob, they rolled up on who they wanted to hit, put a gun behind their ear and hit them. They didn’t shoot up a whole block and risk hitting civilians. These guys, they’re such cowards, they just shoot, shoot, shoot and last night, they didn’t even hit each other. And you’d just think they’d realize, this sort of attention is bad for business.”

I even went through a riff on how holding the gun sideways, like characters do in the movies and gangbangers are said to do in imitation, is just freaking stupid, and explains why these knuckleheads shoot so many innocents and so often fail to hit each other. But I kept my language neutral, like we were talking about other people who’d come here to cause trouble. And I felt a pressing need to keep talking because it felt like a silence could be really dangerous. “I just think,” I said, “that going forward, if we can return to the way things had been we’ll be fine. But if something like this were to happen again, it’s going to be a whole different story. You know what I mean?”

“Yeah,” my neighbor said.

“Cool,” I said.

I shook his hand.

I shook the new guy’s hand again. He looked at me, out from under his eyebrows, not saying anything, his jaw set tightly, and I wasn’t sure if I had just bought myself a world of trouble or sent a very effective message. I’m still not sure if that conversation had any real effect at all. But this I do know: I’ve never seen the new guy again, and both my neighbors — the young one and Chuck the old head — flat out disappeared for several months. Since they’ve returned, the occasions on which we see some skeletons lining up outside Chuck’s house are awfully rare. But what was correlation and what was causation? I have no idea. And I recount my own little story of urban pioneering a bit sheepishly. For all I know, I talked to a couple of guys on the very fringes of the drug game or out of it altogether, who had no real involvement and no real power to create any changes. What I do know, however, is that the neighborhood’s steady upswing has continued. In fact, the changes throughout South Philadelphia are profound.

Coffee shops and brew pubs are springing up in neighborhoods that once consisted of nothing more than private residences and the occasional hair salon or pharmacy (some legal, some illicit). As for my neighborhood, which realtors call the Graduate Hospital area, the stats are impressive. A Fels Institute study on what they called  Southwest Center City — defined as Broad Street to Grays Ferry Avenue and South Street to Washington Avenue — found that of 533 vacant properties catalogued in 1998, 91 percent of them had been or were in the process of being renovated 10 years later. That is a staggering shift, and it in part explains why I felt like drilling into one truly distressed neighborhood for this edition of the Top 10 Drug Corners.

Southwest Center City — defined as Broad Street to Grays Ferry Avenue and South Street to Washington Avenue — found that of 533 vacant properties catalogued in 1998, 91 percent of them had been or were in the process of being renovated 10 years later. That is a staggering shift, and it in part explains why I felt like drilling into one truly distressed neighborhood for this edition of the Top 10 Drug Corners.

More personally, my block is safer now than it was six years ago. We haven’t had any gunfire on the block since that night (I’ve heard gunfire just once in the last few years, and it sounded like it was blocks away). We had a run of burglaries a few years ago and nothing since. Our neighbors remain as authentic and decent and dependable as any man could wish. And while the rest of America’s housing stock suffers, this slice of Philadelphia continues to grow. A whole stack of ‘luxe condos just opened up across from us with prices spiking well past the sublime and into the ridiculous half-million dollar range. And they’ve sold.

We considered moving. But we took a good long look at some other houses in other neighborhoods and determined we like it better where we are. The history we’ve already developed with our neighbors is something that can’t be replicated. And we have reason to believe that here, at least, appearances do represent a new reality.

The Top 10 Drug Corner In Philadelphia 2011 was made possible by an enterprise reporting grant from J-Lab and The William Penn Foundation