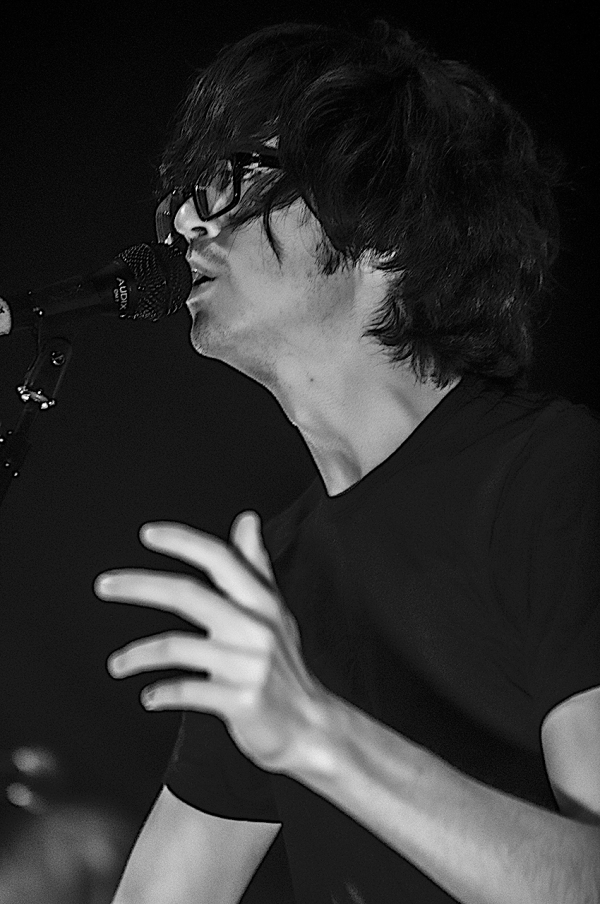

Photo by MATT SHAVER

I first heard Car Seat Headrest last spring, driving through Southwestern Pennsylvania mountain roads with my mom, on Jenny Eliscu’s satellite radio show. As Will Toledo [pictured, above] alternately screamed and spoke the lyrics of “Bodys” in a matter-of-fact tone, my mom laughed out loud, saying “What is this depressing shit you listen to?” Typical baby boomer parent, unable to understand my millennial malaise.

Six months later, I look up at Toledo on the stage of Union Transfer as he sings that same song off of the 2018 re-release of his 2011 DIY triumph, Twin Fantasy, rocking a tight-fitting black top with black harem pants, looking like some kind of indie-rock genie. Since climbing to the mainstream from that Bandcamp breakthrough seven years ago, he’s become an unfiltered voice for the often-inexplicable anxiety and depression my generation feels every day. And in the throbbing chorus of this second song of the night, Toledo gave us a way to clear out those tensions through the exact kind of dancing he sings about in it.

Car Seat Headrest started the set with an aggressive cover of Lou Reed’s “Waves of Fear,” before plunging into the mosh-pit-inducing “Bodys,” which careened right into Teens of Denial’s stop-start hit “Fill in the Blank,” all of which sang the body electric and turned the sold out crowd into a writhing throng of interpretative dance. Car Seat’s touring lineup includes the three members of the Naked Giants, who opened the show, freeing up Toledo from guitar duty to lead said dancing and try out some artsy moves that only a lanky white dude in flowy pants could make comfortably awkward. Despite playing for a total of nearly 90 minutes, the band performed only thirteen songs, splicing in “America (Never Been)” from 2014’s How to Leave Town and a mashup of Teens of Style’s “Something Soon” with a cover of Neil Young’s “Powderfinger.”

Toledo’s monotone delivery of the deeply emotional poetry behind Car Seat Headrest is only half of the band’s appeal to so many young people right now. These epic songs, which can span anywhere from three to thirteen minutes in length, stretch into visceral noise rock solos between the verses, exorcising the loneliness and depression they speak of in a cleansing wave of still-catchy distortion – the kind that kept Toledo shaking his hips all night. A big part of the cultic allure of Car Seat Headrest is the band’s underdog success story, and the self-empowerment that comes from seeing someone as messed up in the head as the rest of us rocking hard in front of thousands.

In typical twenty-first century style, CSH fans have discovered each other in online forums, finding common ground between their private narratives and Toledo’s introspective confessionals re: drugs, relationships, and the weird norms of social settings. Hence the proliferation of Will Toledo look-alikes who turn up at his shows to touch the hem of his garment. But despite their obvious devotion, Toledo kept his crowd interactions brief, maintaining a stoic demeanor for the majority of the performance. That is, until the band played “Destroyed By Hippie Powers,” and the drummer plucked a kid out from the frenzied crowd to play cowbell onstage. He stood miles below the band in height, slamming the hunk of metal with a drumstick with a fervor that pushed him ahead of the beat, his dad barging through the field of drunken adolescents in an attempt to film the whole thing.

Afterwards, the band members shot each other amused glances of wide-eyed disbelief, making guesses about the precocious child’s age in stuttered half-sentences. It was then that the whole room seemed to realize just how far this music has travelled across time and space in the last eight years, from the backseat of a high school car in the leafy exurbs of the nation’s capital to the hearts and minds of the next generation at a sold-out show in Philadelphia. And in this brief and shining moment, Toledo couldn’t help but smile.

Don Babylon, a trio of new Philadelphians, opened the show with a cross between Slim Harpo, Johnny Cash, and Kurt Cobain, seamlessly weaving the styles and tropes of those legends into original work. Next came the Naked Giants who also traffic in this kind of rockist genre-blending, though they lean more heavily on psychedelia and surf rock, with a hint of Led-Zeppelin-like guitar heroics as their fingers cascaded up and down the necks of their instruments. — SOPHIE BURKHOLDER