EDITOR’S NOTE: This is interview first published back in July when Dave Alvin was touring in support of the 25th anniversary of the release of The King Of California. We are reprising this interview in advance of his appearance at World Cafe Live tonight as part of The Reverend Horton Heat’s Holiday Hayride, featuring 5,6,7,8’s and The Voodoo Glowskulls. Enjoy.

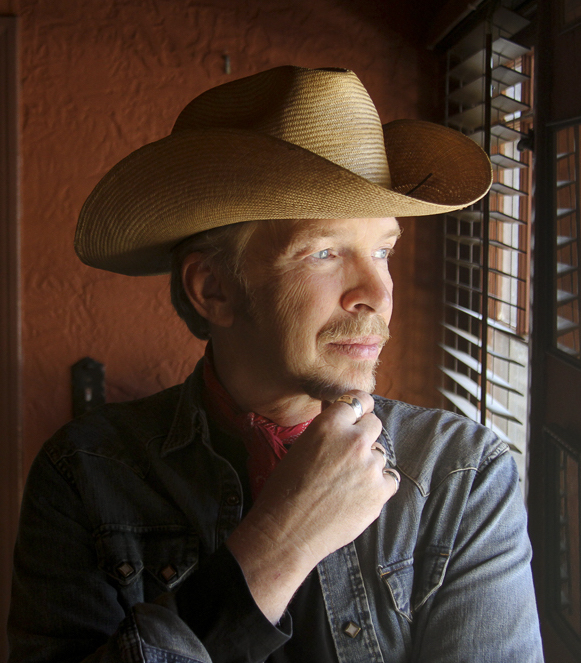

BY JONATHAN VALANIA Americana standard-bearer Dave Alvin is a national treasure. His first band, The Blasters, formed with his brother Phil, schooled a whole new generation of young punks about the glories of early to mid 20th Century American music: Blues, rockabilly, country, Tex-Mex. As guitarist for X and The Knitters he continued bridging the divides between punk and roots music. He was always a hot-shit electric guitar player who let his brother do all the singing and songwriting, but by the end of the ’80s he struck out on his own and after a few albums of trial and error he found his voice as a singer and songwriter with 1994’s The King Of California, now recognized as a modern classic of the Americana/alt-country/No Depression scene. This year marks the 25 anniversary of its release. Alvin is currently on a tour in support of the just-released 25th Anniversary reissue of the album — remastered and re-packaged with bonus tracks — that brings him to World Cafe Live

BY JONATHAN VALANIA Americana standard-bearer Dave Alvin is a national treasure. His first band, The Blasters, formed with his brother Phil, schooled a whole new generation of young punks about the glories of early to mid 20th Century American music: Blues, rockabilly, country, Tex-Mex. As guitarist for X and The Knitters he continued bridging the divides between punk and roots music. He was always a hot-shit electric guitar player who let his brother do all the singing and songwriting, but by the end of the ’80s he struck out on his own and after a few albums of trial and error he found his voice as a singer and songwriter with 1994’s The King Of California, now recognized as a modern classic of the Americana/alt-country/No Depression scene. This year marks the 25 anniversary of its release. Alvin is currently on a tour in support of the just-released 25th Anniversary reissue of the album — remastered and re-packaged with bonus tracks — that brings him to World Cafe Live this Saturday (July 20th) Wednesday December 11th. Last week we got Dave on the horn to talk about the making of the album, some of the back story about the front and back cover art, his development as a singer and a songwriter, as well as a couple bonus questions about schooling The Gun Club’s Jeffrey Lee Pierce in the sepia-toned rapture of early 20th Century rural blues music.

PHAWKER: The now-classic King Of California is celebrating its 25th anniversary. It was recorded the day after  the Northridge earthquake, which was a pretty big deal Tell me, where were you that day or what was your experience with that quake.

the Northridge earthquake, which was a pretty big deal Tell me, where were you that day or what was your experience with that quake.

DAVE ALVIN: Well it was actually– well, we recorded it the same day. And the quake came at like 4:30 in the morning, and we were due to be in the studio at 11 AM, and it– the effect that it had besides– basically a huge chunk of Southern California lost power with the quake, and then there was a lot of damage. The guy that was supposed to be playing bass on the record was a guy named Larry Taylor. Plays in Tom Waits’s band, and was in Canned Heat, blah blah blah. Larry’s house got hammered, so Larry was off the session. So we had to go scrambling to find a bass player and we couldn’t find anybody until the next day. So the first day of recording was done sort of without a bass player. The area around the studio was also hammered. Like a building right across the street, an old apartment building from the 1930s was devastated. And so it just had– the mood was kind of apocalyptic — sporadic power outages and crumbling buildings, you know? So it was, it just kinda had this mood of “Well, if we can get through this, then we’re meant to make this record.”

PHAWKER: In the press materials for the album you are quoted as saying ‘This was the album when I figured out to let the song tell me what it sounds like’ instead of the other way around — elaborate on that a little bit, explain what you mean.

DAVE ALVIN: Well, you know, when I grew up, professionally, writing songs for a band to play, a specific band to play, and for a specific voice — my brother Phil’s voice and the band was the Blasters– and whenever it, no matter what the band is, whether it’s the Rolling Stones or U2 or Soundgarden, you know, there are certain rules that bands have when it comes to the songs, every band’s rules are different. You don’t go into say, Soundgarden and say “Hey, I wrote a polka!” You know what I mean? And maybe the song is supposed to be a polka, you know? So with the Blasters what had happened was just basically I’d bring in a song, the band would rearrange it into a style or key that worked for them. What key is a good key for guitar playing as bass playing as opposed to singing, you know, that kinda stuff. So some of the songs on the King of California record were songs that I’d written for the Blasters that when I wrote them I thought of them as ballads, like sensitive ballads. And of course, you take it to the band and we turned it into rock and roll rhythm blues numbers. You know, loud.

And that’s fine, that’s all valid. But what I wanted to do on this record, because for a guy like me, I don’t know what record’s gonna be my last one. And I don’t mean that in a sense of mortality, I mean it in the sense of– in the business sense, you know, if the Rolling Stones decide to do an album of all polkas, their record label well let them make another record after that. You know what I mean? ‘Well, you know, Mick, we haven’t sold diddly of this Rolling Stones polka record, but what else you got?’ I don’t get that luxury. I mean, luckily I sell enough records now to guarantee that I will make more. But I still go in with the attitude of “well, this could be my last one because it may not sell,” and if it doesn’t sell then I’m at the Burger King asking you what you want on your burger.

So I wanted to get, when I did King of California, I thought, “Well this might be my last record and I wanna get these particular songs right. I just wanna get them recorded right so that when I’m dead and gone, somebody can say oh, that’s not a bad version.” You know what I mean? And so the way to do that, the way to answer your question, the way to do that is if the song says it’s a polka, then the song is a polka. If the song says it’s a ballad, then the song is a ballad. If it’s a blues  song, it’s a blues song, you know? And on and on.

song, it’s a blues song, you know? And on and on.

PHAWKER: Now the bulk of the album was recorded live in the room, with everyone sitting in a circle around the microphones looking at each other hootenanny-style. But because the band the band was able to play quietly, you’ve talked about how this was the moment when you kind of found your voice as a singer — how your voice was able to lead the songs, pull the songs forward. You finally stepped out of your brother’s shadow as a vocalist I think with this record.

DAVE ALVIN: Yeah, as close as I can get to being one, yeah. The producer, Greg Leisz, who was is one of the greatest musicians I’ve ever known — Greg’s on every record just about ever made, it’s easier to listen to records that Greg is not on, you know…he’s not on Sergeant Pepper’s and he’s not on Exile on Main Street, but just about everything else of note, he’s on. So he’s had a lot of experience in the studio with singers and this and the other. And he was a close friend of mine and was good at hearing whatever was in my voice that was a good thing, and how to access it. And sometimes when you make records– you can ask any artist this, any singer– the vocals usually what’s done last, and the producers tend to be more worried about bass and drums. So recording the way that I like to record, which is everybody in the room at the same time, when you’re playing electric the vocals can take a backseat to the drums, you know? It’s like “Whoa, I can’t sing over that.” But in an acoustic setting, and with the right musicians, then yes, the vocals could lead the band into “okay, we’re gonna get loud here, we’re gonna get quiet here, we’re gonna do this, we’re gonna do that,” and you know, just like as if I was James Brown or Van morrison or something.

It’s just, you need the right musicians that are playing the song and not playing their instrument, if that makes sense. Most musicians, probably myself included, are like “Hey I’m playin’ good! I’m hittin’ the right notes!” You know, ‘I don’t care about songs, I’m playin’ good!’ And so you need musicians that play the song, listening to the song. I’ve had guys that are great musicians come into the studio and say “Well, I don’t hear anything on this song. I think it sounds fine, you don’t need me.” That’s a great musician.

PHAWKER: Like the famous saw about jazz: it’s about knowing when not to play. Let me ask you about the circumstances that inspired the writing of “Born On The Fourth of July.” It sounds almost like you’re just literally sitting out on the steps, smoking a cigarette, looking down, the Mexican kids are playing down below, shooting off fireworks, and the song just kinda writes itself from there. Is that kinda…

DAVE ALVIN: No, yes and no. The event– it’s based on a true event in my life, but that was like, it was like ten years or seven years previously, it was back when I had been a fry cook, you know. And my girlfriend at the time and I, she had her day job and I had mine and it was, life was pretty disappointing, you know what I mean? I remember that that particular Fourth of July I wasn’t a songwriter at that point, I never– I didn’t even think that I’d ever be a songwriter, but I remember sitting there going “This is memorable,” you know? “This is memorable, I will remember this.” And so then yeah, seven or eight years later when I was a songwriter, a musician and no longer a fry cook, I always carried that image around, and it finally dawned on me, ‘okay, this is how the song goes, this is how you do it.’

And then once I decided this is the song, then it did kind of write itself, I was actually with my girlfriend at the time– my other, my entirely different girlfriend and an entirely different life, but we were with some friends at a bowling alley and she and I were just sitting there drinking beer watching our friends bowl badly and it suddenly just popped into my head, and I turned to my girlfriend and said “Let’s go home” and about two hours later called her up and said “Okay, this is why I took you home,” and sang her the song. So it did come, once I decided, this is a song that came quick.

PHAWKER: Tell me about the circumstances around the cover shot and the back photo. All this time, I’ve always thought you were sitting in a box car, sort of hobo style…

DAVE ALVIN: [laughs] I can see that, I can see that, yeah.

PHAWKER: But that’s not the case at all ‘cause I just saw the uncropped version of that photo and you’re sitting in the ruins of a building or something at sunset– tell me about that.

DAVE ALVIN: Yeah, it was the photographer, Beth Herzshaft, and I were driving around Central California taking photographs for a possible album cover and then we were driving down this two lane highway in the middle of nowhere up in this area called Cuyama Valley that no one knows about, and I looked over and to my left and out on this ranchlands I could see this old adobe ruin of a house. So, you know, turned the car around, and we trespassed, we opened up the ranch gate, drove down, literally it’s just sage brush and hillsides, nothing else out there. Drove down a mile, half mile to the ruin, started taking pictures, and it just happened to be right at sunset. So it was like we got that perfect sunset shot. So you know, it was a little bit of that California history with the adobe and all that, and also, you know, it just had a certain magic.

PHAWKER: And tell me about the back cover photo.

DAVE ALVIN: You’re looking at the San Andreas Fault right there. That’s a road, a little road– that road leads into a thing called the Carrizo Plain National Monument. The little mountain range there is called the Temblors, you know, for the tremors of the earth.

DAVE ALVIN: Can’t get more California than the goddamn San Andreas fault.

PHAWKER: Yep, that plays right into the album title. One last thing on the album here and then I have a Gun Club question for you, because I’m a big Gun Club fan.

DAVE ALVIN: Sure.

PHAWKER: Hang on one second, my page of questions just blew away. On the 25th anniversary edition of this has some bonus tracks and one of them is the song, the beautiful instrumental called Riverbed Rag that for whatever reason didn’t make the album proper, and I’m looking at the liner notes here and it says that that’s inspired by exploring the San Gabriel River bed as a kid.

DAVE ALVIN: Well, because Greg Liesz, who produced the record, is doing all the dobros and lap steel and all that on the record, he grew up next door– well, the town next door to me, he grew up in a place called Santa Fe Springs, which is on the east side of the San Gabriel River in Downey where I grew up, so on the west side of the San Gabriel river, and when we first became friends that’s kinda what we bonded over — the San Gabriel river, basically this long river bed that goes from the San Diego mountains down to the Pacific Ocean, and so yeah I just kinda wrote up a little ragtime blues instrumental for Greg and I to play on. And the only reason it didn’t make it on the record– I wanted it on the record to kinda liven it up– some of the songs are pretty down, lyrically, and so then I wanted something to help bring things up, but the record was just too long with it included. But I think it’s a fine piece, we’re doing it live ‘cause it gives us a chance to play.

PHAWKER: This riverbed– both of you guys sort of played and explored there as kids,is that right?

DAVE ALVIN: Yes, sir, yep.

PHAWKER: Any interesting stories of, you know, did you find any buried treasure or a dead body…

DAVE ALVIN: Yeah, you could ask Greg about his. Mine was, when I was a kid that area was wild, you know? There were hobo jungles, as they used to call them, down there the banks were kinda lined with bamboo, real thick bamboo, so when  you’re a kid you’d go into the neighborhood bamboo jungles, and there was, you know, jackrabbits and rattlesnakes and coyotes and all that kinda stuff, just kinda like “Great! This is the greatest place on earth!” you know? “And hobos? Oh my god, rattlesnakes, rabbits, coyotes and hobos? Where do I sign up?” It wasn’t the Mississippi, it wasn’t Mark Twain’s Mississippi, but it was my Mississippi.

you’re a kid you’d go into the neighborhood bamboo jungles, and there was, you know, jackrabbits and rattlesnakes and coyotes and all that kinda stuff, just kinda like “Great! This is the greatest place on earth!” you know? “And hobos? Oh my god, rattlesnakes, rabbits, coyotes and hobos? Where do I sign up?” It wasn’t the Mississippi, it wasn’t Mark Twain’s Mississippi, but it was my Mississippi.

PHAWKER: Excellent, excellent. So I just wanted to ask you to relay– there’s this great interview you did with TK [16:05] called Bored Out where you were talking extensively about Jeffery Lee Pierce and early… all kinda stuff, that I was just reading through that’s just fantastic, and you talk about how you and your brother were the ones who turned [Gun Club mainman] Jeffrey Lee Pierce onto the blues. That before that he more or less had zero knowledge of the blues.

DAVE ALVIN: Well, I wouldn’t say he had zero knowledge. He had knowledge– it was limited to B.B. King, that kinda stuff, sorta the obvious people you get into when you first get into blues. What we schooled him on was country blues. He had never really gone deep in that, and so a lot of people when they hear country blues for the first time, the first time they hear Son House or Skip James, people like that, yeah, they can flip because that’s just such amazing music. And he would come over to where my brother and I lived, and we had a bunch of old 78’s and we’d sit around and drink and shoot the shit and play old records, and say ‘Okay, now you gotta listen to this guy, you gotta listen to this guy, see what he’s doin’ here? See what he’s doin’ there?’

PHAWKER: Right.

DAVE ALVIN: And yeah, Jeffrey had been, you know, he was a reggae kinda guy for a while or was passing himself off as a reggae guy. And he was also a Blondie guy.

PHAWKER: Right. I believe he was the president of the Blondie fan club.

DAVE ALVIN: Yes he was, yes he was. A couple of the tracks on the first Gun Club album, “Preaching the Blues” and “Cool Drink of Water,” — you know, he learned those from us.

PHAWKER: That was a very seminal experience, I mean I think that really informed the beginnings of the Gun Club and the– to my mind, their greatest album, the Fire of Love album.

DAVE ALVIN: He wasn’t some technical wizard on guitar. But what he did with what he knew was great, he knew how to make it work. The Gun Club started using a thing that was in short supply in those days, which was dynamics. So that’s why especially that first album the dynamics were just excellent. Jeffrey Lee understood like James Brown Live At The Apollo was a favorite record of his, and that record is all about dynamics. And when to bring the band up, when to bring the band down. In those days, and strictly on that scene, it wasn’t a lot of dynamics. It was just ‘1-2-3-4- GO!’… and Jeffrey  Lee figured out just not for the blues covers that he did, but for his own songs, he figured out whether it was “For the Love of Ivy” or “She’s Like Heroin to Me,” we can make up for the fact that we’re not the best musicians by playing the music really, really well. Really getting into, again, kinda what I was saying earlier about understanding the song, playing the song and not the instrument.

Lee figured out just not for the blues covers that he did, but for his own songs, he figured out whether it was “For the Love of Ivy” or “She’s Like Heroin to Me,” we can make up for the fact that we’re not the best musicians by playing the music really, really well. Really getting into, again, kinda what I was saying earlier about understanding the song, playing the song and not the instrument.

PHAWKER: To follow up on that, you mentioned this repeatedly in that interview that the Gun Club couldn’t draw flies in LA at that time, I don’t understand why?

DAVE ALVIN: Because they came along at a period of time– they weren’t punk enough for the hardcore kids. It wasn’t “ONETWOTHREEFOURONETWOTHREEFOUR,” you know, and in those days that was when– when the Gun Club, if they woulda come out two years earlier, three years earlier, it woulda been a different story in a way. But they came out when all the focus on the Southern California scene as far as punk rock goes, if it wasn’t strictly on Circle Jerks or Black Flag then it wasn’t punk rock. And so those kinda kids that were into those bands never latched on to the Gun Club. You know, The Gun Club would do gigs with those bands, and they would be — it would just be unappreciated, let’s put it that way. And then they weren’t rootsy enough or good enough musicians for the Roots Rock crowd, for the rockabilly crowd or the blues crowd or the country… so they had to find their own niche. And Jeffrey stood by his vision and that when it got to Europe and– it started in New York, where they had a little buzz in New York, but it was really in Europe because Jeffrey was enough of a madman — and the Europeans love American madmen. They don’t like normal Americans, but ‘Goddamn, that’s guys insane, you know, let’s watch him!’ In Europe by that time had already punk rock was basically dead already by the time the Gun Club got there they didn’t have to deal with that [punk rock snobbery] and the audience just kinda reacted to them just purely, “Hey that’s a really cool band.” LA was mired in that — you know, that’s one of those things that killed the LA scene was that cookie cutter thing of what’s punk rock, what’s not. Anyway, I got another interview coming in, so nice talking to you, brother.