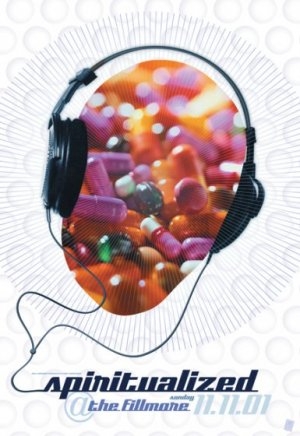

EDITOR’S NOTE: This story originally appeared in the November 2001 issue of Magnet and reported in the immediate aftermath of 9/11. We are reprising it here to mark the auspicious occasion of Spiritualized performing at The Fillmore Philly on Good Friday, in support of the new LP And Nothing Hurt. Enjoy.

BY JONATHAN VALANIA

Somewhere Over The North Atlantic, Sept . 25, 2001

Ladies and gentlemen, we are floating in space—35,000 feet above the Earth, to be exact. We’re on our way to Ireland to tag along on a Spiritualized tour. It’s gonna be fun, but there are some risks involved. As Americans, we’re traveling under the threat of death from Osama bin Laden, The Evil One, who lives in a cave. During the course of our trip, you might feel a little like Salman Rushdie without the bodyguards; hell, we all feel like that now. My advice is do like they do in Ireland: Keep drinking. I should also tell you we’ll be arriving in the middle of the latest flare-up in Northern Ireland’s on- again/off-again civil war, or The Troubles, as they call it over there, where one man’s terrorist is another man’s freedom fighter.

Despite all this, or maybe because of it, I promise this trip will be worth your while. We’ll witness the rebirth of one of the world’s great live bands. We’ll suckle sweet Guinness from the mother teat of Ireland while Spiritualized blows wave after shiver-inducing wave of ecstatic peace across our bodies. And we’ll all come together. As the world crashes down around our ears, for a few minutes at least, we’ll feel safe. This, my friends, is a very in-demand vacation package these days. Plus, we’ll get to talk in circles for many hours with Jason Pierce, the band ‘s auteur. Ever since the release of 1997?s Ladies And Gentlemen We Are Floating In Space, Pierce has become the Head Shepherd In Charge of the Space-Rock Flock. We’ll talk about drugs and God and volcanoes. About broken hearts and broken bands and broken records and how to fix them. And, in the end, we won’t really have learned anything at all. Except this: Music, not religion, is the opiate of the masses. Religion is more like the cocaine of the masses — and the world doesn’t need any more cocaine right now. Cocaine kills.

Before our arrival in Dublin, however, you should understand the events that have conspired to bring us together with Spiritualized are long and complicated, stretching back more than 100 years. For all intents and purposes, they begin in…

Sils-Maria, Switzerland, September 1888

Friedrich Nietzsche, the German philosopher, writes Twilight Of The Idols, which contains the following passage: “For art to exist, for any sort of aesthetic activity or perception to exist, a certain physiological precondition is indispensable: intoxication.” A year later, Nietzsche would, quite literally, go insane.

Planet Earth, 1889 -1979

A lot of stuff happens.

Rugby, England, 1980

Fourteen-year-old Jason Pierce walks into a pharmacy and makes his first purchase of recorded music. The album: Raw Power by the Stooges. A decade later, having adopted the nom de rock J. Spaceman, he’ll form a band called Spiritualized, which makes modern psychedelic/rock music. One particularly astute critic will describe Spiritualized’s music as “Stooges for airports.” Coincidence? Not really.

Rugby, August 1984

Pierce receives a government grant to attend Rugby Art College, which he promptly misuses to purchase an electric guitar and amplifier. Pierce meets classmate Peter Kember (a.k.a. Sonic Boom, a.k.a. Peter Gunn), son of a wealthy importer. Kember ‘s initial impression of Pierce is that he’s “someone who is very smart, but very lazy.” Kember and Pierce bond over a mutual interest in psychedelic music and recreational drug use. Pierce turns Kember on to the Stooges. Kember reciprocates by turning Pierce on to the Cramps, Velvet Underground and heroin. They form a band that combines all four influences and call themselves the Spacemen. Later, they’ll add a “3? to the end of the moniker, borrowing the number from an early Spacemen gig poster that reads “Are Your Dreams At Night 3 Sizes Too Big?”

guitar and amplifier. Pierce meets classmate Peter Kember (a.k.a. Sonic Boom, a.k.a. Peter Gunn), son of a wealthy importer. Kember ‘s initial impression of Pierce is that he’s “someone who is very smart, but very lazy.” Kember and Pierce bond over a mutual interest in psychedelic music and recreational drug use. Pierce turns Kember on to the Stooges. Kember reciprocates by turning Pierce on to the Cramps, Velvet Underground and heroin. They form a band that combines all four influences and call themselves the Spacemen. Later, they’ll add a “3? to the end of the moniker, borrowing the number from an early Spacemen gig poster that reads “Are Your Dreams At Night 3 Sizes Too Big?”

“Taking drugs to make music to take drugs to ” is their mantra and their methodology. At the height of Just Say No, they’ll openly sing the praises of mind –altering substances to the media. They’ll crown themselves kings of the one-chord drone, funneling White Light/White Heat-era Velvets and pre-mental-hospital 13th Floor Elevators through a mesmerizing prism of noisy trance rock. And they’ll do it all sitting down, as do the audience members. In fact, some lie flat on their backs. You seem, many of them have taken drugs to listen to music to take drugs to.

Via E-mail, Oct. 9, 2001, 2:07 A.M.

MAGNET: What role did drugs play in the creative process of Spacemen 3?

Peter Kember: It’d be a lie to understate their role, but plenty of folk have found our music enough to replace drugs for consciousness alteration. I always felt I was merely a conduit or antenna receiving moods/feelings and translating them into sound forms and lyrics in order to re-transmit the experiences that encapsulated our lives .

MAGNET: You have spoken very candidly about your heroin use during the band. Was that something you and Jason did together?

PETE KEMBER: Sometimes. Not much, Jason took very little drugs during the S3 period—except lager and Jack Daniel’s. I turned Jason and other band members on to LSD, etc., and though we used heroin together occasionally, I think it was always more my weakness. Not to say hash, weed, speed, coke and mushrooms didn’t figure — they did frequently. I never believed in turning on friends to smack. Jason made his own choice, I have not been a social heroin user ever; (it’s) more a personal habit. It interferes surprisingly little, but for the effects of its criminalization.

New York City, 1989

I have tickets to see Spacemen 3 and the Butthole Surfers. It will be Spacemen 3?s first-ever show in America. I’ve already taken drugs to listen to music to take drugs to when I find out at the club that Spacemen 3 has cancelled its tour. Word has it the band members couldn’t get work papers because of drug convictions—which only serves to reinforce their narco chic. Twelve years later, Pierce will tell me the tour was called off because he “had a nasty fall” down a flight of stairs. Kember will tell me the tour was canceled because Spacemen 3 broke up.

London, 1990-1997

Pierce forms a new band with girlfriend/keyboardist Kate Radley and everyone in Spacemen 3 except Kember. Inspired in equal parts by Aretha Franklin’s Amazing Grace and the French inscription on a bottle of Pernod absinthe (“Spiritueux Anise”), Pierce christens the project Spiritualized. In 1992, at the height of British dream-pop, the band releases Lazer Guided Melodies, an aptly titled collection of ambient headtrip rock carved with clinical precision. ”We got £3,000 to make a record, and I wanted to make it sound like Electric Ladyland,” says Pierce. “Pete would not let Spacemen 3 do anything in the studio that couldn’t be replicated live. So it was a massive freedom.” Pierce sinks every pound into the recording, sleeping in the drum booth to save money on a hotel room.

In 1995, Spiritualized — which, by now, has already undergone the first of many lineup changes — releases Pure Phase, a woozy step forward in Pierce’s never-ending quest to mix the perfect prescription of sound and texture. Unable to choose between two different sets of mixes of the album, Pierce enlists the service s of trip-hop producer/Spring Heel Jack member John Coxon to accomplish the nearly impossible trick of running two mixes of each song simultaneously, one in each speaker.

In 1995, Spiritualized — which, by now, has already undergone the first of many lineup changes — releases Pure Phase, a woozy step forward in Pierce’s never-ending quest to mix the perfect prescription of sound and texture. Unable to choose between two different sets of mixes of the album, Pierce enlists the service s of trip-hop producer/Spring Heel Jack member John Coxon to accomplish the nearly impossible trick of running two mixes of each song simultaneously, one in each speaker.

Then some other stuff happens, deeply personal stuff, about which Pierce now has little or no recollection — and even if he does, he certainly doesn’t care to share it. Which is understandable. In Britain, particularly in London, musicians lead more of a fishbowl existence than their American counterparts. The members of the British music press are so bitchy and gossipy, nobody would be surprised to learn they walk around all the time with hair dryers on their heads, their hands soaking in a manicurist’s fingerbowl. When Pierce and Radley split up and she turns around and marries the Verve’s Richard Ashcroft, it becomes the hook onto which most of the reviewers hang their interpretations of Spiritualized’s next album, Ladies And Gentlemen We Are Floating In Space. Much to Pierce’s consternation, the reviews always say something along the lines of “Guy from Spacemen 3 pours out his broken heart in a space-rock masterpiece.”

“It’ s a lovely idea that I wrote that album about our breakup, but it’ s just not true,” says Pierce.” I wrote I’ve Got A Broken Heart’ a year before Kate and I split up. The math doesn’t support it.”

“I’ve Got A Broken Heart” may be the emotional center of Ladies And Gentlemen, but “Cop Shoot Cop,” a junkie confessional in the tradition of Lou Reed’s “Heroin,” is its philosophical treatise. It sounds, on the surface, like druggy braggadocio (“Hey man, there‘s a hole in my arm where all the money goes”), but by the end, the lyrics turn more ambivalent, in much the same way “Heroin” ends with “I guess, but I just don’t know.” The first couplet of the chorus is “Cop shoot cop/l believe, I believe that I have been reborn,” but Pierce follows it up with “I haven’t got the time no more. “This is as close as Spiritualized gets to Just Say No. For reasons that will become apparent by the end of this story, it’s important to know that famed New Orleans swamp rocker Dr. John laid down some of his trademark voodoo piano on Ladies And Gentlemen’s “Cop Shoot cop.” Remember that: Dr. John.

New York City. April 16. 1998

A year and a half of touring in support of Ladies And Gentlemen earns Spiritualized a well-deserved reputation for delivering some of the most transcendental live shows in recent memory. In a bid to play “the highest show in the world, ” the band performs at Windows On The World on the 107th floor of the World Trade Center.

London, April 1999

Spiritualized guitarist Mike Mooney, bassist Sean Cook and drummer Damon Reece receive certified letters from Spiritualized’s manager informing them that “according to clause 1d of your contract your employment with Spiritualized has now been terminated.” Mooney, Cook and Fleece form a band called Lupine Howl and go public with how Pierce made them walk the plank from the good ship Spiritualized, painting him as a money-grubbing tyrant too zonked on heroin to have a conversation with.

“Sean [Cook) is not stupid; he’s quite bright,” says Pierce. “Some of the later things that he said were meant to damage me in the press, and obviously some of it sticks.”

Pierce says the old unit mutinied, demanding more money from a band that was already operating at a loss (profits from album sales were negligible due to the amount spent on packaging and recording) On top of that, he says, they made booking tours—Spritualized’s one source of income, outside the occasional Volkswagen commercial—impossible by demanding a day off between shows and turning their noses up at dates if the money wasn’t good enough. “So I retired them,” says Pierce.

Via E-mail. Sept. 20, 2001, 2:22 P.M.

MAGNET: How central were-drugs to the creative process in Spiritualized?

SEAN COOK: [At first], no one in the band really took drugs except (bassist) Willie (Carruthers) and myself. They have always played some part in my approach to music. After Pure Phase, drugs were more prevalent in the band—the effect they had was sometimes creative, sometimes destructive.

MAGNET: To what extent did drugs play a role in making it undesirable to remain in Spiritualized?

SEAN COOK: Heroin can turn a person into either a mumbling geriatric or an egocentric little kid and often a mixture of both. This can place a strain on a band.

MAGNET: What couldn’t you do in Spiritualized that you can do in Lupine Howl?

SEAN COOK: Being in Lupine Howl is quite similar to being in Spiritualized, except the fact that there are no assholes in the group.

Abbey Road Studios, London, June 1999

Work begins on Let It Come Down, Pierce ‘s titanic orchestral opus. Prior to actually rolling tape, Pierce spent a solid year in pre-production, transcribing hours of microcassette tapes filled with his hummed musical ideas into charts for horns, strings and a gospel choir. Although some songs on Let It Come Down feature more than 100 musicians, recording is wrapped up in a tidy three weeks. In what’s become standard operating procedure for Spiritualized albums, Pierce spends the next year mixing and remixing the songs into a state of grace — or the closest approximation thereof.

solid year in pre-production, transcribing hours of microcassette tapes filled with his hummed musical ideas into charts for horns, strings and a gospel choir. Although some songs on Let It Come Down feature more than 100 musicians, recording is wrapped up in a tidy three weeks. In what’s become standard operating procedure for Spiritualized albums, Pierce spends the next year mixing and remixing the songs into a state of grace — or the closest approximation thereof.

Mt. Etna, Sicily, Italy. Aug. 29, 2001

The highest active volcano in Europe, Mt. Etna has been erupting on and off for 300,000 years. In mythology, it ‘s regarded ‘as the forge of Vulcan, the god of fire, as well as the home of the Cyclops. Knee-deep in black sand and flecked with the grey ash that falls like snow flurries / a man dressed in a silver furnace suit makes his way toward the edge of the lava flow. He’s followed by a small film crew that records him lip-synching to songs from Let It Come Down. Mr. Spaceman passes two veteran vulcanologists from Hamburg, Germany, who’ve set up their equipment as close to the lava flow as they deem safe. Curious to learn what kind of fool would take such risks, the vulcanologists follow the film crew. They’re thrilled to know the man in the furnace suit is Jason Pierce. It turns out their Spiritualized fans. As far as anyone can tell, this is the first time a rock star signs autographs on the side of a volcano.

Philadelphia, Sept. 10, 200 1:11 P.M.

I’m packing for our trip to London to interview Spiritualized tomorrow. I hold in my hands a ticket for a flight from Philadelphia International Airport to Logan International Airport in Boston, where I’ll catch an American Airlines flight to London.

New York City, Sept. 11, 2001, 9:15 A.M.

Centuries are big, lumbering things that rarely start or end on time. Often, it takes some cataclysmic event to shoo them away and make room for the next one. On this day, the 20th century officially ends. And I’m not going anywhere.

Logan International Airport, Boston, Sept. 25, 2001

I have a new plan: catch up with Spiritualized on tour in Ireland. Airport security asks me to remove my shoes so they can be x-rayed. I can’t help but think they’re two weeks too late.

The Gresham Hotel, Dublin, Ireland. Sept. 26, 2001

If it weren’t for the lighter, Jason Pierce would be lighting the next cigarette off the last. And there’s always a next cigarette. Dressed in bone-white leather trousers and a very spaceman-ish pair of silver sneakers, his triangle of a face framed by a mottled, Jaggeresque mop, Pierce looks hale and healthy in that sort of pale, just -stepped-out-of-the-rain way the British have about them. He no longer has the dark, raccoon-like circles that have shown up under his eyes in photos in recent years. His speaking voice is just above a whisper, with only the vaguest hint of a British accent. “Fantastic” is his superlative of choice, and he uses it liberally, placing special emphasis on the middle syllable. He comes across as sharp, focused and preternaturally calm-the same attributes that enable him to spend a solid year searching for the sweet spot on the mixing faders.

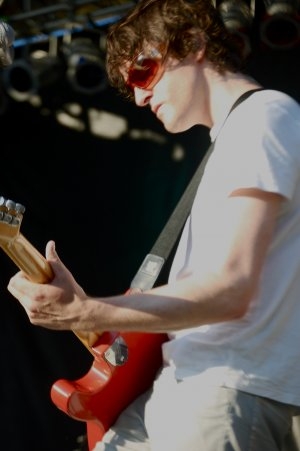

I tell him I’ve come to praise him, not to bury him. “To be honest, it makes no difference to me,” he says. Pierce is one of the few people I actually believe means it when they say things like this. Pierce has exactly 30 minutes before he has to head over to the Ambassador Theatre for soundcheck, In this time, we learn a few basic facts: He was born 35 years ago in Rugby. His father “wasn’t around:’ so his mother was forced to raise Pierce and his two brothers on government assistance checks. Somehow, his mother scraped together enough money to buy him an acoustic guitar when he was seven years old. He vowed to honor her sacrifice by mastering the instrument. Twenty-eight years later, it remains a work in progress. “To be honest, I don’t even play that well now, ” he says through a plume of cigarette smoke. “There are only four or five chords I can play.” Which is three or four chords more than he ever needed in Spacemen 3.

The Ambassador Theatre, Dublin, 9 P.M.

It’s a sold-out show and expectations are high. Let It Come Down holds the number one slot on the Irish album charts. There are reviewers on hand from the NME, London Times and Irish Independent. This is only the third time Pierce has publicly performed with his new live unit, a 13-piece outfit that includes a full brass section. The only holdovers from the previous lineup are keyboardist Thighpaulsandra and saxophonist Ray Dickaty. Pierce elects to open with the narco-blues of “Cop Shoot Cop.” The song starts as a slow Big Easy crawl-voodoo tambourine, swampadelic piano, watery guitar-wriggling sensually like a catfish in the mud. The bar is crowded and noisy. The Guinness is starting to kick in. Suddenly, the band hits the first towering crescendo, and everyone’s knees buckle slightly as the room rises eight miles high. The air thins and oxygen masks fall down from the ceiling. Ladies and gentlemen, we are once again floating in space. Hallelujah. Amen. Over and out.

Somewhere In The Middle Of Ireland , Sept. 27, 2001

Last night, the Troubles started again. While Spiritualized was negotiating ecstatic peace in Dublin, there was a war going on in Belfast. That’s 104 miles away, according to my rental-car map. On a global scale, that’s just up the street. Like all wars in the 21tst century, I’m fast learning, Ireland’s war is vague and mean and largely invisible. It only becomes visible in brief flashes of violence and brutality. Shit gets broken. People die. Nothing changes except the particulars of the shit that gets broken and the people who die. Up until recently, that was an average of 100 people a year in Northern Ireland.

A few hours earlier in Belfast, rioters pelted paramilitary police with 186 petrol bombs. Gunfire was exchanged. As I drive north to Derry (about 70 miles away from Belfast), where Spiritualized is scheduled to perform tonight, I stop for gas and pick up a newspaper. The front page has a photo of children winding their way through the burned-out hulks of overturned cars on their way to school. As I proceed north through tiny villages, there are other signs that the Troubles have renewed. At one point, I pass through a military check point, where soldiers sto p me and ask the nature of my business. Later, while passing through the lilliputian village of Omagh, I notice British paramilitary office rs fanning out along the street and taking cover in the doorways of shops, rifles drawn. Schoolgirls file by in a nervous swoosh of white kneesocks and plaid skirts.

Derry, Northern Ireland, Sept. 27 , 2001, 5:03 P.M.

Upon arriving in Derry, I immediately manage to get completely lost, ending up on the very spot where the Bloody Sunday massacre occurred. Grim, two -story murals mark the occasion on the sides of buildings. Spiritualized is playing in a tiny club called the Nerve Centre. I make my way up to the dressing room, where the band sits around a giant conference table laid out with beer and cold cuts. This is Pierce’s first time in Derry. “It’ s amazing to be here after seeing this place on the news every night for 30 years, ” he says. From th e open window comes the crackle of what sounds like gunfire echoing across the town. The room falls silent. This is life during wartime. You are always thinking about the unthinkable, and you have no choice other than to accept what was once unacceptable.

The Nerve Centre, Derry, 9:20 P.M.

Club date s by bands like Spiritualized are rarer than sunshine in Derry, as most British bands fear to tread in Northern Ireland. Needless to say, tonight’s show is a sellout. Even in this room with a less-than-state-of-the-art sound system-it feels more like a high-school auditorium than a rock club-Spiritualized sounds beatific.

Three or four songs into their set, Pierce and Co. have the crowd in rapture. They hoist their pint glasses in the air and sing along with every word like it’ s “Auld Lang Syne” over and over again. By the time the band launches into the amphetamine zoom of “Take Me To The Other Side,” a song Pierce wrote back in his Spacemen 3 days, the crowd is jumping up and down in unison until the floor buckles. It’s like standing on a hardwood trampoline. Spiritualized closes with “Lord Can You Hear Me,” another old Spacemen 3 song, which Pierce re-recorded for Let It Come Down as a full-blown gospel number. The song has been singled out by critics for being somehow insincere or inauthentic because Pierce isn’t a religious man. But in much the same way adults write all the best children’s songs, all good art draws its power from the ability to pretend persuasively. The song is positively massive, glorious and righteous in that your -arms-are-too-short-to-box-with-God sort of way. It’s one for the hymnals, and tonight it sounds like a benediction.

As Pierce leaves the stage and heads for the dressing room, he’s pulled aside by a farmer who tells him he plays Ladies And Gentlemen to get his sheep to come to him. “I’ve tried other music, but they won ‘t have it,” he says. They say good music will always find its audience. Sometimes, it’s on the side of a volcano; sometimes, it’ s in the middle of an Irish pasture. Or a war.

Backstage , The Nerve Centre, 11:20 P.M.

Everything Jason Pierce touches turns to drugs. Everything. Spiritualized’s music is all about sound as drugs and drugs as lyrics. All songs star Pierce’s alter ego: Little J., the fucked-up boy who numbed the pain but killed the joy, who sometime has his breakfast right off of a mirror and sometimes right out of the bottle. “Just me and my spike in my arm and my spoon” is his idea of ” love in the middle of an after noon .” In case all this wasn ‘t obvious enough for you, the artwork for Ladies And Gentlemen was designed to look like pharmaceutical packaging. In publicity photo for the album, the group stood behind the counter of a drugstore, as if waiting fill your prescription. He’s even named his one-year-old daughter poppy. When Pierce talks about putting on “the highest shows on Earth,” he means it literally. The Wolrd Trade Center. Toronto ‘s CN Tower. His dream is to play in Bastfjord, Norway, nearly 200 miles above the Arctic Circle, which is latitudinally one of the highest inhabited places on Earth. “There is a whaling station up there, so it’s not impossible,” he says. ”We are trying to make it work. ” If all goes according to plan, the Aurora Borealis will provide the light show.

The Lupine Howl guys have been telling anyone who ‘d listen that Pierce was deeply immersed in heroin around the time of Ladies And Gentlemen, but the only drugs I see him take in the time I spend with him are a few beers and a couple cartons of cigarettes . On first listen, Let It Come Down sounds like a rehab album. There are songs called “The 12 Steps” and “The Straight And Narrow, ” not to mention the album title itself. But Pierce insists Let It Come Down isn’t a confessional: There was no rehab, no evangelical embrace of sobriety. And even if there was, it would be tacky to make hay of it in the press. Upon closer inspection, “The 12 Steps” reveals itself to be a condemnation of rehab albums, a backhanded slap at celebrities who use their redemption as a hook for hawking whatever product they ‘re endorsing. Besides, Pierce is tired of talking about drugs. “It comes across as a boast when you talk about it,” he says. “Besides, it’s not as if it isn’t apparent in the music. At any rate, it’s my personal life, and it’s not for public display.” He will confirm that, yes, he has done drugs, but he says he never had a drug problem. And yes, the drugs still work when you do them right. “The smart guy is the one who can drink half a glass of cider and get absolutely out of his mind,” he says.

Whenever cops or customs officials ask what kind of music he makes, Pierce always tells them Spiritualized is a gospel group, which is only a slight stretching of the truth. There’s a blurry line between gospel and space rock-both want to take you higher-and Pierce has made it his mission to erase the line between the two. As far back as Pure Phase, Pierce has been incorporating the elation triggers of gospel-angelic choirs, soaring organs, towering horns-into his arrangements . But Pierce isn’t a believer. He’s borrowed the medium, but he’s not buying the message. Remember, music, not religion, is the opiate of the masses.

MAGNET: So you don’t believe in God?

PIERCE: I’m very empirical, and I like my science to be good science.

MAGNET: Do you believe in the soul?

PIERCE: Not (one) that transcends the body when you die.

MAGNET: You think that when we die, we just cease to exist, we become worm food?

PIERCE: Yeah.

MAGNET: How can you be so rational, especially as someone who’s spent his life making music about achieving these sorts of heightened states? It’s all about irrational things.

PIERCE: ‘Cause they are achievable. If I say I believe that music can make you feel fantastic or make the hairs on the back of your neck stand up, I know that’s true because I have experienced that. But if I say music is the key to a fantastic afterlife, that’s a kind of belief. That’s like saying I believe that pigs can fly. When you start a sentence with “I believe,” you get into the realm of fantasy.

MAGNET: So you believe these states of elation and ecstatic consciousness you can experience with music or drugs are all just chemical reactions in your brain and not intimations of divinity?

PIERCE: Yes.

MAGNET: That’s rather depressing, I think.

PIERCE: No, it’s not-it’s really exciting. The more you understand things, it doesn’t make them more depressing. Understanding how things work doesn’t take the excitement out of things.

MAGNET: When you deny the possibility of divine mysteries and reduce everything to a series of molecules bumping into each other randomly that triggers some kind of reaction, that to me just makes the miracle of life and creation seem small and colorless and devoid of poetry.

PIERCE: But it has been anyway, whether you like it or not.

MAGNET: I agree science has done a remarkable job of figuring out how most everything works, but how did it all begin and where did it come from? All this just happened by chance?

PIERCE: Let it come down, let it come down.

Philadelphia, Oct 24, 2001

Spiritualized is playing at the Trocadero, an old vaudeville/burlesque theater turned rock club, located in the city’s Chinatown section. Across the street from the Trocadero is the Greyhound bus station, where just the other day the police found enough C-4 plastic explosives in an abandoned locker to reduce the entire block to rubble. The bus station is only a few blocks from where I live. I can’t help but think of that old Spacemen 3 gig poster, only now it says, “Are Your Nightmares 3 Sizes Too Big?”

It’s starting to get to me. Every other minute, I think, “The terrorists have come up with the smartest bomb there is: fear. They built it in a cave in Afghanistan, and they’ve been dropping it on our heads every day since September 11. They killed 3,000 people in one hour. They are here, and we can’t even see them. Sometimes, we think we see them, but we can never be sure. They look and dress like so many other innocent people who live, work, study or visit here. They use our Constitution as camouflage. They walk among us and between us. They use us as human shields. Our armies are useless in this kind of war—they only know how to shoot and kill things, and you can’t shoot anthrax—but we send the troops to Afghanistan and beyond. But the war is here, where the enemy has slipped through our mail slots into our homes to kill us. William S. Burroughs was right: A paranoid-schizophrenic is a guy who’s just out what’ s going on.

Then I think, “Maybe popular music will get better because of this.” Maybe this whole fucking thing will act like a giant pop-culture enema and just blow all the shit that’ s been clogging up for the last few years. Maybe people will want something more than Jailbait T&A and backward-baseball-cap attitude. Surely, people will be hungry for something a little deeper, something a little more spiritualized than Britney or Christina. I mean, what does Fred Durst or J. Lo or the artist formerly known as Puff Daddy have anything to do with anything that’ s happening right now and in the foreseeable future? When seven-month-old babies have anthrax, who’s gonna be impressed with Eminem’s uncanny ability to somehow make “faggot” rhyme with “suck my dick”? After September 11, all that seems so last century, so petty and shallow and mean. Maybe, just maybe, millions of people will want to hear a song like “Lord Can You Hear Me.”

I tell this to Pierce shortly before he goes onstage. I don’t expect him to buy it. It’ s the kind of thing usually shrug off; it’s too simple, too cute, too much of a Hollywood ending. It’s like journalists saying Ladies And Gentlemen was his breakup record and Let It Come Down is his rehab record.

This is the last of our interview sessions, and Pierce has been resisting all my attempts to tie his story into a neat little package with a pretty bow on top. He simply won’t participate in the making of his own myth, and even though this is rendering my job nearly impossible, I have to respect him for it.

By this point, I’ve almost finished this article: It’ s this travelogue told in dated journal entries, and it’s kind of about war and peace and God and drugs. All I need is for Pierce to kindly step into this story, which I don’t think is too much to ask because it isn’t too far from the truth. But he steps out of every circle I try to draw around him with my questions. It’ s not like he’s being a jerk or anything. He’s just not going to talk about drugs. He’s not going to talk about his personal life. He’s not going to give me pithy little sound bytes. He’s not going to comment on the World Trade Center, even though he understands why I would ask him to. It’ s just that, you know, it would be shameless and exploitative for him to do so.

I’ve run out of questions, but the tape recorder is still rolling, so I tell Pierce my theory about what happened on September 11 and everything after may well change popular music for the better. That maybe the time has finally come for a band like Spiritualized. He smiles and takes a long puff on the latest in a chain of Marlboro lights. Then he looks down at my tape recorder. “I can’t comment on that, but you are the second person that has said that to me,” he says, exhaling. “The first was Dr. John.”

Ladies and gentlemen, let the war on bad music begin.

SPIRITUALIZED PERFORMS @ THE FILLMORE FRIDAY APRIL 19TH