Illustration by @KingJediah via Instagram

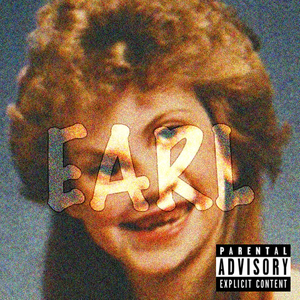

BY SEAN HECK In 2011, Los Angeles-based hip-hop collective Odd Future Wolf Gang Kill Them All were at the zenith of their fame. By then, the group of boisterous young rappers, producers, crooners, skaters, fashion designers and hype men had collectively released 12 mixtapes, with a few members showcasing a large array of distinct influences, personalities, and sounds. The group’s ringleader, Tyler the Creator, seemed to get his kicks from simultaneously worrying and intriguing white Americans with repulsive, predatory lyrics about rape, murder and mutilation juxtaposed with murky, jazzy, and at times quirkily beautiful piano and synth driven self-produced instrumentals. Singer Frank Ocean, who would later go on to become the group’s most commercially successful artist, had established himself as a promising creator of sticky, earworm pop and emo-soul  R&B ballads (e.g. “Swim Good” and “Novacane”). Of particular interest, however, was one Earl Sweatshirt, born Thebe Neruda Kgositsile. The mysterious young rhymesayer had a debut mixtape under his belt that established him as a witty, whipsmart young lyricist with a densely-layered and double-entendre-ridden verbal prowess. He was the ignition key to Odd Future’s blast into internet superstardom. He was the new Jay-Z! He was the new Nas! He was the new Slim Shady reincarnate!

R&B ballads (e.g. “Swim Good” and “Novacane”). Of particular interest, however, was one Earl Sweatshirt, born Thebe Neruda Kgositsile. The mysterious young rhymesayer had a debut mixtape under his belt that established him as a witty, whipsmart young lyricist with a densely-layered and double-entendre-ridden verbal prowess. He was the ignition key to Odd Future’s blast into internet superstardom. He was the new Jay-Z! He was the new Nas! He was the new Slim Shady reincarnate!

And he was…missing.

That’s right. The most sought-after and linguistically-gifted spitter of the collective was cut off from the outside world and didn’t even know about Odd Future’s newfound fame during the group’s peak. Why? Well, his mother had sent him to an all boys’ reform school in Samoa, presumably because she heard Earl, Earl Sweatshirt’s lyrically grim, borderline horrorcore debut mixtape (which features a song called “epaR”, or “rape” simply spelled backwards), and/or had seen some of the efficaciously ridiculous and provocative content on the OFWGKTA Youtube channel. No one knows the exact terms of Earl’s maternal exile. Either way, his fans were revolutionary in their demands for his return; they demonized his mother for daring to enact parental guidance over her son (who was a minor, by the way), they started the #FREEEARL social media campaign, and they built up expectations of his “comeback album” that far exceeded those of Dr. Dre’s never-to-exist Detox. Droves of fans eagerly flocked to their preferred streaming services when they were finally graced with Earl Sweatshirt’s long-awaited debut album, and they were met with…Doris.

The disappointed ellipsis above is not intended to suggest that Doris is unsatisfactory in any way, but rather to recreate the stark and bitter truth that was cast upon some of Earl’s more enthusiastic and icon-obsessed fans: that Earl Sweatshirt would never be the next Nas—the next Eminem—the next Jay-Z—and he was never trying to be.

It seems that his enforced MIA status during the height of Odd Future’s fame was, in a way, the best thing ever to happen to Earl Sweatshirt. His mental health and substance abuse issues remain a serious point of concern to be sure, but at least he has stayed out of trouble enough to maintain his impressive ability to calmly articulate his struggles to true fans, new and old, willing to decipher his tightly-packed and, at times, decidedly esoteric bars. Quoth Earl: “I’m a surviving child star.” This is indeed an apt and optimistic sentiment, but given the fates of some of Earl’s contemporaries, it is also a sobering reminder of the tempestuous path of the typical young Internet-age rapper. Earl has evaded much of the turbulence that has eclipsed the careers of many a modern young hip-hop artist; others have not been so lucky. For example, 6ix9ine’s short, underwhelming career has been plagued by numerous unrelenting legal issues, from racketeering charges to suspected involvement in a child’s sexual performance. Tay-K, at just 18 years old, is facing time for capital murder. XXXTentacion was facing serious legal consequences for the alleged grisly abuse of his girlfriend before he was gunned down in front of a motorcycle shop at the tender age of 20. Mac Miller and Lil Peep both died during prosperous times in their careers from Fentanyl overdoses, aged only 26 and 21, respectively. It isn’t too far-fetched to speculate that Earl Sweatshirt’s absence from the limelight during a time in which he would have prospered most but was ill-equipped to handle it, may have saved his life.

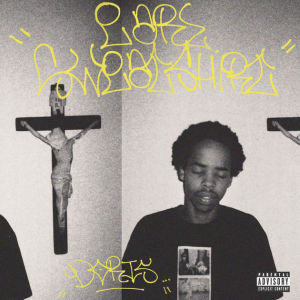

And so we had 2013’s Doris. Far from the grand and triumphant return fans and critics alike were expecting, the then 19-year-old’s debut album was nevertheless a marvel. It’s a complicated, honest, and shockingly introspective realization of the next-level material hinted at in Earl’s pre-exile work. The record is rife with nutty instrumental detours and anti-pop, sample-heavy beats laden with insular lyrics shedding light onto Earl’s maternally-imposed exile and its consequences, the complications of his return to stardom, and the effect his father’s general lack of presence had on him. Earl maintains and even sharpens the ability that he displayed on Earl to pour out dizzying, filled-to-capacity bars, but here he uses his wordplay as a vehicle for honest self-exploration instead of gross-out imagery and juvenile violence.  Rather than a comeback album, Doris feels like the creation of a road-weary young man, wise and experienced beyond his years both in terms of industry presence as well as general life experience.

Rather than a comeback album, Doris feels like the creation of a road-weary young man, wise and experienced beyond his years both in terms of industry presence as well as general life experience.

Earl’s second full-length studio album, I Don’t Like Shit, I Don’t Go Outside: An Album by Earl Sweatshirt is even more understated than Doris but far more antisocial. As opposed to his debut’s near 45-minute run time, the sophomore LP clocks in at just under 30 minutes. Whereas Doris features high-profile guests on almost every track (such as fellow Odd Future members, RZA, and Mac Miller), I Don’t Like Shit finds Earl delivering on a promise made in the album’s final track, “Wool”: “On my momma I been limiting my features.” With the exception of “Wool”, every track is produced by Earl under the pseudonym “randomblackdude.” The only high profile feature on the album is Vince Staples’s opening verse on the aforementioned “Wool.”

Elsewhere, Earl speaks on his addiction, panic attacks, breaking up with a significant other, and the death of his grandmother with such unadorned and bitter honesty that one can’t help but to listen to him as he lists his grievances. As with its predecessor, I Don’t Like Shit… was instantly hailed by critics, but Earl Sweatshirt maintained his refusal to capitalize on the hype that surrounded him at the dawn of the decade. Rather, he was coming into his own as a daring lyricist and an honest articulator of his damage: addiction, isolation, death, heartbreak and mental illness. It seemed as if his journey inward would only continue as he searched for salvation through his art.

And then…silence.

Until the very end of 2018, Earl Sweatshirt was relatively silent. Absent any new releases since I Don’t Like Shit, I Don’t Go Outside, fans did not know what to expect. Other than solemn words about the death of friend and fellow artist Mac Miller via Twitter this September and a cancellation of tours due to anxiety and depression this past summer, there was radio silence from Earl Sweatshirt, and the hip-hop climate had changed a lot since his last release in 2015.

That silence lasted until the November 2018 release of “Nowhere2Go,” Earl’s first single in three years, followed closely by the release of his third studio album, Some Rap Songs. If I Don’t Like Shit, I Don’t Go Outside presented Earl Sweatshirt spending a little too much me time alone in his home, then this new release can be seen as tantamount to the now 24-year-old rapper barricading himself off in a shack  in the middle of nowhere and throwing away the key. Its generic title is an apt reflection of how little Earl now cares about selling himself to an audience. He is so subdued in this under-25-minute release that one might not grasp how significantly Earl is baring his soul on its 15 iTunes-preview-length tracks. The album’s production is sample-heavy, loopy, lo-fi, and choppy and the instrumentation strikes a perfect balance: sometimes soothing and silky smooth, sometimes loud, dissonant, and full of hard left turns and jarring audio clips.

in the middle of nowhere and throwing away the key. Its generic title is an apt reflection of how little Earl now cares about selling himself to an audience. He is so subdued in this under-25-minute release that one might not grasp how significantly Earl is baring his soul on its 15 iTunes-preview-length tracks. The album’s production is sample-heavy, loopy, lo-fi, and choppy and the instrumentation strikes a perfect balance: sometimes soothing and silky smooth, sometimes loud, dissonant, and full of hard left turns and jarring audio clips.

Earl’s delivery, at once deadpan and dense, may be hard to digest for new listeners at first. Vocally, he is raspier and more subdued in his delivery than he has ever been, invariably sounding like he chain-smoked two packs of Newports and two grams of loud before he got on the mic. However, he is also at his most reflective and his most poignant, rapping about familiar struggles such as addiction, mental illness, family and loss (his father, the late poet Keorapetse Kgositsile, passed away mere months before the album’s release), seemingly in real time. Most of the tracks here are vignettes that give the listener a voyeuristic look into the bruised psyche of not just a creatively exhausted artist, but rather a vulnerable human being struggling with many things at once. The closing instrumental track ends the album on sonic high note with a woozy cover of Hugh Masekela’s “Riot”. The cheerful cover’s upbeat guitar riffs, anthemic percussion, and jubilant trumpets make it feel like a realization in Earl that, despite his issues, he is going to be okay.

The spotlight has chased Earl Sweatshirt in some form or another throughout the entirety of his career and, as is showcased by the ethos and the tone of his three major label releases, he has been doing his level best to avoid it. Whereas many of today’s Internet-famous rappers feel the need to do anything they can to remain in the conversation, Earl Sweatshirt garners attention precisely by not demanding it. He invites the listener into his personal life in a manner that suggests that he does not really care whether he/she looks or not. Earl does not want to please obsessive fans. He does not want to be memed into stardom. He does not want to live fast and die young like many of his contemporaries. Rather, he aims to encapsulate the human experience in daring pursuits of sonic innovation. His mission is to bear his soul regarding issues of loss, loneliness, addiction, and spiritual struggle, chiseling at these issues with loquacious lyrical finesse in order to evolve into a more stable, healthy, and self-aware person. It is clear to see that he is well on his way and, in an age of colorful rappers that are more spectacle than substance, he is the unassuming, plainly dressed poet that we need.

EARL SWEATSHIRT PERFORMS @ THEATER OF LIVING ARTS MARCH 29TH