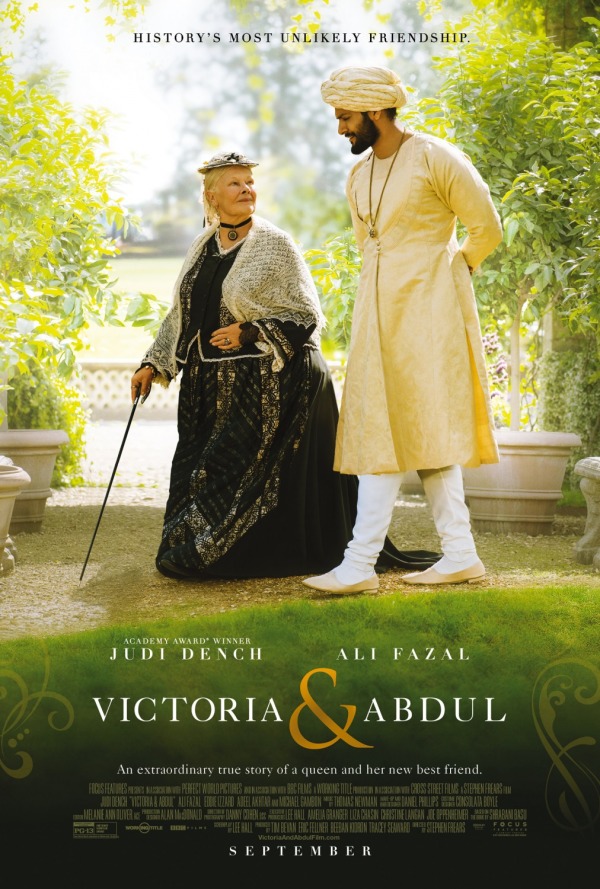

VICTORIA & ABDUL (Directed by Steven Frears, 152 minutes, 2017, USA)

BY CHRISTOPHER MALENEY FILM CRITIC Because I am a son of Ireland, Queen Victoria was never my favorite historical figure. Her reign brought hard times for Ireland, as well as many other countries around the world. The Victorian era included the annexation of then-Zululand and India, the transportation of thousands to Australia, two horrible conflicts in Crimea and South Africa, the repression of sexual liberties, the scramble for Africa, and more. But how responsible was the Queen for the actions of her state? If she was even aware, can history blame her for the actions of her ministers and generals? Victoria & Abdul, a new film from the BBC and Focus Features, would have us believe that the personality of Queen Victoria was far removed from the policy of her empire and her subjects, and that history should treat the two quite differently.

BY CHRISTOPHER MALENEY FILM CRITIC Because I am a son of Ireland, Queen Victoria was never my favorite historical figure. Her reign brought hard times for Ireland, as well as many other countries around the world. The Victorian era included the annexation of then-Zululand and India, the transportation of thousands to Australia, two horrible conflicts in Crimea and South Africa, the repression of sexual liberties, the scramble for Africa, and more. But how responsible was the Queen for the actions of her state? If she was even aware, can history blame her for the actions of her ministers and generals? Victoria & Abdul, a new film from the BBC and Focus Features, would have us believe that the personality of Queen Victoria was far removed from the policy of her empire and her subjects, and that history should treat the two quite differently.

We begin with Mohammed Abdul Karim (Ali Fazal), a clerk in the Agra jail. If, like Victoria, you aren’t familiar with Indian geography, the dialogue will fill you in that Agra is where the Taj Mahal is located. Abdul is selected to present a Mughal coin to the Queen-Empress (Dame Judi Dench) for her Golden Jubilee, and the movie wastes little time in quickly getting Abdul and his comrade Mohammad Buksh (Adeel Akhtar) to the Jubilee, where Abdul does the unthinkable and makes eye contact with the Queen. Instead of having him punished, Victoria takes a liking to our handsome Indian Muslim and commands that he become her personal footman, confidant, and soon teacher, or Munshi. While the rest of the court is flummoxed by her interest in Abdul, he proves a kind and caring teacher who brings the empress out from her status-imposed isolation.

While the story arcs depicted in the film — Victoria’s friendship with the Munshi, her interest in Indian culture and language, and the court’s dislike for Abdul — are all matters of historical record, the opening credits make clear that the film is only loosely based on actual events. Instead, the movie attempts to vindicate Queen Victoria from the high crimes of empire through her contact with Abdul, leaving the ministers, courtiers and soldiers to take all the blame. This is perhaps the logical extension of the ‘few rotten apples’ theory.

Abdul is a perpetually wide-eyed, naive, non-European who shows the Queen the beauty of cultural contact by explaining how all of life is woven together like a rug woven by prisoners in Agra. He absolves her sins — wearing the crown jewels of India in a broach, for one — with his innocent subservience to the figurehead of an empire, a tired trope at this point. The household staff are generally power-hungry, cruel, and as two-dimensionally conniving as Abdul is sincere. Again, parts of this movie are true to life, but on a symbolic level the film leaves much to be desired. Mohammed Buksh, Abdul’s servant and one-time equal, is the only character who understands the rapacious forces at play, but even his viewpoint feels manufactured, a token gesture to appease those pesky historians. His death offscreen, while a catharsis for Abdul, seems to drive home the fact that the filmmakers had no idea how to show him as a round character.

Despite all this, I honestly enjoyed Victoria & Abdul in many ways. Abdul is charming, and his friendship with Queen Victoria is fun to watch. He shows how contact with a different culture can transform the lives of those who are willing to change, and how such transformations face blowback from reactionary forces intent on maintaining their hold on power no matter the cost. Where this narrative works against racial prejudice, it can be a force for good. Where it intends to ameliorate the British Empire of its crimes, not so much.