MARK HARRIS: What is striking about Being There, the portrait of a man who relates to no one but to whom everyone relates, is that it represents both a synthesis of many of the qualities in Ashby’s earlier movies and a sharp break from them. The film is initially quiet; its mood is hushed, almost austere. We meet Chance, a simpleminded, middle-aged man-child who has spent his entire life in the Washington, D.C., home of a wealthy, unseen benefactor, as he goes about what is clearly an unvarying ritual. He wakes up, gets out of bed, combs his hair, and prepares to spend his day doing the only two things that interest him—tending to his garden and watching one of the television sets that are present everywhere. Television is a constant in Being There the way music is a constant in many of Ashby’s other movies; he is never careless about the meaning or content of background noise. Here, he views TV as a presence that can take over if you let it—and sometimes, he lets it.

In these opening moments and in many that follow, the cinematography is dark—no sunlight or fresh air has penetrated these cloistered suites of wealth and privilege—and the tone is initially chillier than in most of Ashby’s other movies; Being There is not interested in swiftly ingratiating itself or telling you what it’s going to be. The world you’re watching is private, and Sellers—an actor whom, in 1979, audiences would have watched expectantly, waiting for him to tell them it was okay to laugh—is a placid cipher, giving nothing away.

Who is Chance? In the cultural syntax of Kosinski’s work, he is a kind of holy fool, a man who knows nothing yet knows everything, a popular mystical/sentimental trope of the time. In contemporary diagnostic terms, he would be considered to lie somewhere on the autism spectrum. Cultural moralists labeled him the ominous end point of what was, at the time, referred to as “the television generation”—an incarnation of stoic passivity who can express almost no preference other than “I like to watch.” In Sellers’s  determinedly controlled, virtually affectless performance, he is all those things and more, and also less—a blank slate, an emotional dead spot, the eternal “little boy” his late benefactor’s caregiver calls him, and also, in a very quiet way, a clown. MORE

determinedly controlled, virtually affectless performance, he is all those things and more, and also less—a blank slate, an emotional dead spot, the eternal “little boy” his late benefactor’s caregiver calls him, and also, in a very quiet way, a clown. MORE

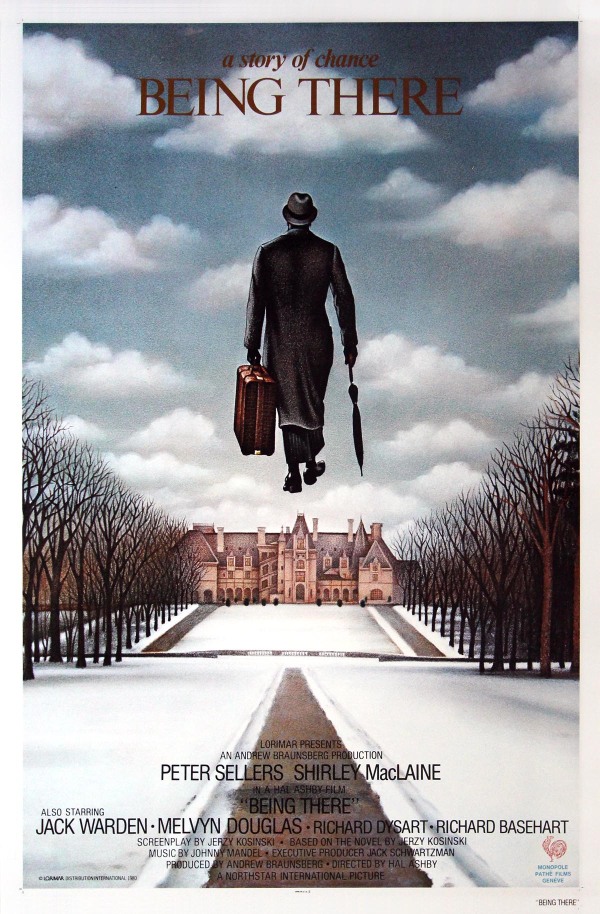

CHICAGO READER: Whereas [director Hal] Ashby’s previous films had been about rebels and outsiders, Being There tells the story of the ultimate conformist—a man who says only what other people want to hear. The film is a fable of sorts. Sellers plays Chance, a childlike man who has spent his entire life in isolation, living in the mansion of a wealthy person who has employed him as a gardener. At the beginning of the film, Chance’s benefactor dies; after an awkward visit from a pair of lawyers, who shut down the home, Chance leaves the estate for the first time in his life. All he knows of the world (apart from gardening) is through watching television, which he does compulsively. He has no social skills, although he’s soft-spoken and eager not to start trouble. When he winds up in the home of a dying presidential adviser, Chance is mistaken for a socialite, and his blank discourse is accepted as political wisdom by a number of important people, including the president.

Adapted from a novel by Jerzy Kosinski, Being There is clearly a statement about the malign influence of television in American life. Chance is the product of TV, and he finds his apotheosis there—first when the president quotes him during a press conference (wrongly assuming Chance’s aphorism about gardening to be about the U.S. economy), then on a late-night talk show, where his laconic shyness is mistaken for wit. Television has made him a passive consumer of images, someone who doesn’t want to interact with others. Yet in a culture dominated by television, he fits right in. Consider the way Sellers’s costars (such as Jack Warden, Shirley MacLaine, and Melvyn Douglas, who won an Academy Award for his work here) play off him: they pretend that Chance knows what he’s talking about, then respond with a kindness and faux-understanding that makes them feel better about themselves. He’s a mirror for their own emptiness and desire not to upset people.

The President’s on-air citation of Chance’s nonwisdom can be read as a metaphor for any time that televisual blandness has overtaken genuine thought in modern politics. Kosinski, who left communist Poland to become a writer in the U.S., saw how political discourse could be replaced by empty sloganeering; he also saw the potential for that in his adopted country. Many have called Being There, both the book and the film, a premonition of the Reagan revolution, which came to power, in part, on the strength of Reagan’s ability to communicate on TV. The deathlike air of the film certainly connotes the end of something big, while the humor comments on the timeless human desire to be deceived by something that sounds good. These opposing elements give Being There an enduring complexity, although sometimes it’s too bleak in its outlook to be laugh-out-loud funny. MORE