Illustration by OLIVER STAFFORD

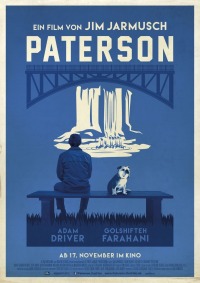

FRESH AIR: I’m Terry Gross. My guest is screenwriter and director Jim Jarmusch. His new movie “Paterson” stars Adam Driver as a bus driver and poet named Paterson who lives and works in Paterson, N.J., and is inspired by William Carlos Williams and his epic poem “Paterson.” The poems Paterson writes in the film are inspired by what he observes in the daily routines of his life. Almost all the poems used in the film were actually written by poet Ron Padgett. New Yorker film critic Richard Brody wrote (reading) Jarmusch has made a movie that’s filled with poetry and that is a poem in itself. We’re going to talk about movies, poetry and music – three of Jarmusch’s passions. The rapper Method Man has a  cameo in the new film. Jarmusch recently made a documentary about the punk band Iggy and the Stooges. His other films include “Stranger Than Paradise,” “Down By Law,” “Coffee And Cigarettes,” “Dead Man,” “Ghost Dog” and “Only Lovers Left Alive.” MORE

cameo in the new film. Jarmusch recently made a documentary about the punk band Iggy and the Stooges. His other films include “Stranger Than Paradise,” “Down By Law,” “Coffee And Cigarettes,” “Dead Man,” “Ghost Dog” and “Only Lovers Left Alive.” MORE

NEW YORKER: Jim Jarmusch is among the rarest and most precious filmmakers of our time, because, at his best—as he is in his new film, “Paterson”—he conjures an entire world of his own imagination. He does so with his wry and tamped-down tone, his loping rhythms, his puckishly frontal compositions, his worn-in sense of design, the winking terseness of his dialogue—and the loving precision of his documentary-rooted observations, which anchor his microcosmic cinematic world, with its austerely whimsical passions, in the world at large.

“Paterson,” the story of a poet and his poems, is set in Paterson, New Jersey, and its protagonist is a bus driver named Paterson, who is played by Adam Driver. Paterson the driver writes poetry; he thinks poetry while walking to and from the depot, he writes in his notebook (his so-called secret notebook) at the wheel of his bus while waiting for his shift to begin; he writes during his lunch hour while sitting on a bench beside his favorite place, the Great Falls of the Passaic River, with his copy of Frank O’Hara’s “Lunch Poems” beside his lunchbox; he writes at his cramped desk in his basement, surrounded by building supplies and hardware. The poems that Paterson thinks and writes are actually by Ron Padgett (who’s cited in the end credits), and the film is filled with them. Jarmusch creates superbly lyrical sequences of shifting multiple exposures, with Driver’s voice reciting Paterson’s (rather, Padgett’s) poems while they’re superimposed on the screen in Paterson’s handwriting. MORE

__________

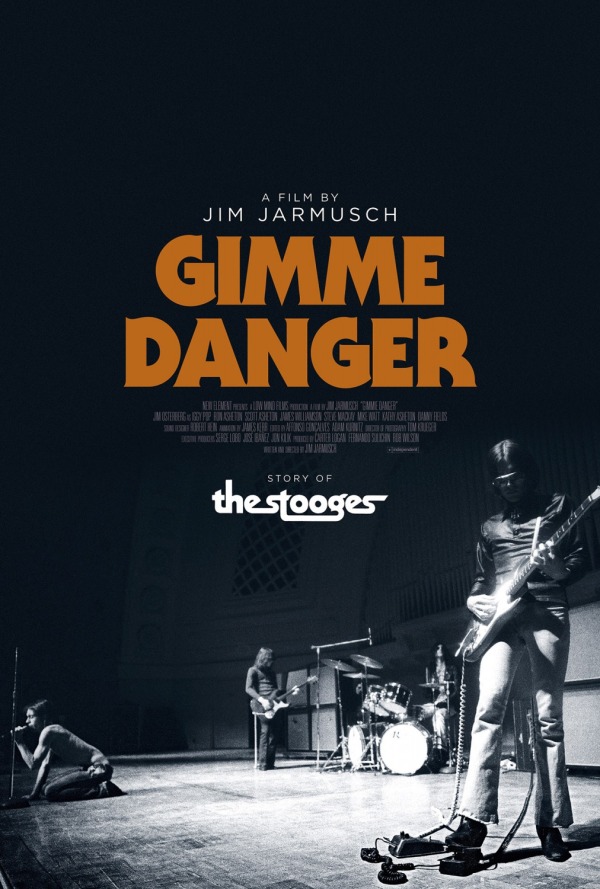

Loud, lewd and anarchic, the Stooges emerged from the dark side of the ’60s like a bad moon rising, and while they were largely misunderstood if not altogether despised back in the day, both their sound (the prototype of both punk and metal) and vision (hearts full of napalm, 10 soldiers and Nixon coming, apocalypse now) would prove prophetic as the Age of Aquarius curdled into the ’70s. James Newell Osterberg — AKA Iggy Pop, the titular frontman for Iggy & The Stooges — single-handedly invented the notion of lead singer as human cannonball, rolling shirtless in broken glass, pissing blood, shitting thunder and leaving behind the unsettling impression that there was nothing he would not fuck, snort or shoot. By his own admission, he was, and to a certain extent still is at the ripe young age of 69, a streetwalking cheetah with a heart full of Napalm, and of course he’s had it in the ear before.

The three seminal albums Iggy made with the Stooges from 1969 to 1973 — The Stooges, Fun House and Raw Power — comprise some of the most primal brick-in-the-face rock ‘n’ roll ever committed to tape. Together or alone, they swing harder than John Holmes jogging in a bathrobe, and comprise the proto-punk Rosetta Stone upon which blank generation enfant terribles like The Ramones and The Sex Pistols would make their stand a decade later. A fairly unimpeachable case could be made for The Stooges being the greatest rock n’ roll band of all time, such is the mission of Jim Jarmusch’s Gimme Danger. Though I agree with the prevailing critical consensus that the film isn’t loud or weird enough, Jarmusch mounts a persuasive closing argument for greatness with a seamless blend of exceedingly rare and largely never-seen-before still photos and 16mm concert footage, clever animations and amusing and instructive talking head interviews with Iggy, drummer Scott Asheton, guitarists Ron Asheton and James Williamson, Mike Watt and Ramones manager/rock n’ roll Zelig Danny Fields, who signed the band to a record deal in 1968 as a junior executive for Elektra Records.

Leathery and louche and sitting atop a skull-encrusted throne, Iggy gets the lion’s share of face time and proves to be a effective narrator of his own legend. We learn that: he grew up in an Ypsilanti trailer park and had shockingly cool and supportive parents. He learned the potent immediacy of monosyllabic language from Soupy Sales and the power of pratfalls from Clara Bell the clown from The Howdy Doody Show, and the apes taught him how to dance. After a brief teenaged tenure as drummer for Chicago bar-band circuit bluesmen, he found his way to Ann Arbor, then a hotbed of radical art and politics, and forms The Stooges with the Asheton brothers and bassist Dave Alexander. “In the Asheton brothers I found primitive man,” Iggy says, explaining how his simian war dance stage moves adrenalized the band’s glorious cosmic roar. Three now iconic but then largely-ignored-if-not-reviled albums and countless chaotic blood-and-broken-glass-flecked, peanut butter-smeared live shows later, it’s all over. But Iggy has the last laugh. “I think I helped wipe out the ‘60s,” he zingers on The Dinah Shore Show, inducing a spit take of knowing laughter from pal/producer David Bowie. Indeed.–JONATHAN VALANIA