![]() BY JONATHAN VALANIA FOR VICE It has been said that the genre of power pop—white man-boys with cherry guitars reinvigorating the harmonic convergence of The Beatles, The Beach Boys, and The Byrds with the hormonal rush of youth—is the revenge of the nerds. Big Star pretty much invented the form, which explains the worshipful altars erected to the band in the bedrooms of lonely, disenfranchised melody-makers from Los Angeles to London, and all points in between. Though they never came close to fame or fortune in their time, the band continue to hold a sacred place in the cosmology of pure pop, a glittering constellation that remains invisible to the naked mainstream eye.

BY JONATHAN VALANIA FOR VICE It has been said that the genre of power pop—white man-boys with cherry guitars reinvigorating the harmonic convergence of The Beatles, The Beach Boys, and The Byrds with the hormonal rush of youth—is the revenge of the nerds. Big Star pretty much invented the form, which explains the worshipful altars erected to the band in the bedrooms of lonely, disenfranchised melody-makers from Los Angeles to London, and all points in between. Though they never came close to fame or fortune in their time, the band continue to hold a sacred place in the cosmology of pure pop, a glittering constellation that remains invisible to the naked mainstream eye.

Big Star was the sound of four Memphis boys caught in the vortex of a time warp, reinterpreting the jangling, three-minute Britpop odes to love, youth, and the loss of both that framed their formative years, the mid-60s. Just one problem: It was the early 70s. They were out of fashion and out of time. Within the band, this disconnect with the pop marketplace would lead to bitter disillusionment, self-destruction, and death. But that same damning obscurity would nurture their mythology and become Big Star’s greatest ally, a formaldehyde that would preserve the band’s three full-length albums — No. 1 Record, Radio City, and Sister Lovers/Third — as perfect specimens of classic guitar pop. That Big Star’s recorded legacy would go on to inspire countless indie sensations is one of pop history’s cruelest ironies—everyone from R.E.M. to The Replacements to Elliott Smith would come to see Big Star as the great missing link between the 60s and the 70s and beyond.

There is a dreamy, pre-Raphaelite aura that surrounds the legend of Big Star. Like the doomed, tender-aged beauties in Jeffrey Eugenides’ novel  The Virgin Suicides, the band’s tragic career would unravel in the autumnal Sunday afternoon sunlight of the early 1970s. The band’s sound and vision hinged on the contrasting sensibilities of songwriters Alex Chilton and Chris Bell. In the gospel of Big Star, Bell was the sacrificial lamb—fragile, doe-eyed, and marked for an early death. After the first two Big Star albums were DOA, Bell quit the band he started. After a failed attempt at a solo career, he succumbed to drug and alcohol abuse, further exacerbated by Bell’s lifelong struggle with depression and his inability to reconcile his homosexuality with his Christian faith, culminating in a fatal car accident in 1978.

The Virgin Suicides, the band’s tragic career would unravel in the autumnal Sunday afternoon sunlight of the early 1970s. The band’s sound and vision hinged on the contrasting sensibilities of songwriters Alex Chilton and Chris Bell. In the gospel of Big Star, Bell was the sacrificial lamb—fragile, doe-eyed, and marked for an early death. After the first two Big Star albums were DOA, Bell quit the band he started. After a failed attempt at a solo career, he succumbed to drug and alcohol abuse, further exacerbated by Bell’s lifelong struggle with depression and his inability to reconcile his homosexuality with his Christian faith, culminating in a fatal car accident in 1978.

?

Chilton was the prodigal son, returning to Memphis after traveling the world, having tasted the bacchanalian pleasures of teen stardom with the Box Tops in the 1960s. Where Bell was precious and naive, Chilton was nervy and sardonic, but the band’s steady downward spiral would set him on the dark path of personal disintegration—booze, pills, violence, and attempted suicide—documented with harrowing lucidity on Big Star’s final album, which, depending on who you ask, was either called Sister Lovers or Third. The album’s shattered sonics and desolate beauty were deemed—by the best ears of major label A&R at the time—as too weird and depressing to release. The album collected dust in the vaults for four years. In 1978, a semi-legit version of the album culled from select tracks briefly surfaced, but it would not be until 1992, some 19 years after its completion, that Third/Sister Lovers was given a proper, high-profile release.

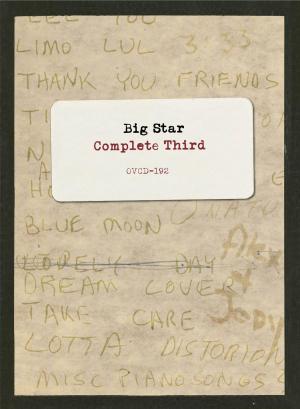

In the wake of Third/Sister Lovers stillborn birth, Chilton would reinvent himself as an irascible iconoclast, seminal new wave/punk progenitor, and semi-ironic interpreter of obscure soul, R&B, and Italian rock ‘n’ roll. He died in 2010, but history will remember him as one of the unwitting founding fathers of the Alternative Nation—his alt-rock sainthood immortalized by The Replacements’ “Alex Chilton”—that rose up in the 80s and 90s, and a direct inspiration for the waves of celebrated indie weirdness that rippled through the dawn of the 21st Century. A new three-disc, 69-track box set called Third Complete collects and curates all the extant recordings—rough sketch demos, alternate takes, unreleased tracks and multiple mixes—from Big Star’s last gasp. It is an embarrassment of riches for the long-suffering faithful and a yellowing road map through the madness and majesty of Third/Sister Lovers for adventurous newbies. Here’s hoping some kid finds it and changes music again.

At the time of his death, Chilton was in the process of mounting a live revival of Third/Sister Lovers set to debut at SXSW. In tribute to Chilton, founding Big Star drummer Jody Stephens, The dBs’ Chris Stamey, Let’s Active’s Mitch Easter, and R.E.M.’s Mike Mills performed Third/Sister Lovers beginning to end in a series of concerts in New York, London, Sydney, Seattle, and Los Angeles. On the eve of the release of Third Complete, we got the R.E.M. bassist/songwriter on the horn to talk about the legend and the legacy of Big Star’s lost masterpiece.

NOISEY: How did you first come to Third/Sister Lovers?

MIKE MILLS: I was familiar with the first two [Big Star albums] before I really paid attention to the third one, and when I did I’m not even sure what iteration of it it was. When I first heard it there was no official release, it was whatever people had cobbled together; it had some of the songs, but not all of the songs. Some of them I loved and some of them I didn’t. I think about this record, some of the songs take a few repeated listenings to truly see what’s going on, and to get the full impact of it, or at least it did for me. I came to it really gradually as I managed to hear all the different versions that came out over those years in the early ’80s.

MIKE MILLS: I was familiar with the first two [Big Star albums] before I really paid attention to the third one, and when I did I’m not even sure what iteration of it it was. When I first heard it there was no official release, it was whatever people had cobbled together; it had some of the songs, but not all of the songs. Some of them I loved and some of them I didn’t. I think about this record, some of the songs take a few repeated listenings to truly see what’s going on, and to get the full impact of it, or at least it did for me. I came to it really gradually as I managed to hear all the different versions that came out over those years in the early ’80s.

NOISEY: Did R.E.M. feel a certain kinship with Big Star given that both bands were comprised of white, southern bohemian types with artistic ambitions that weren’t always met with commercial acceptance?

MIKE MILLS: I don’t think the home towns had anything to do with it really. I don’t remember thinking about that. It was just that clearly, they came from the same musical place as we did, especially Peter [Buck, R.E.M. guitarist] and I, because the songwriting is just so strong, and the guitar playing so amazing, all the instrumentation was really amazing. So the fact that you could be that good at your instruments, and write songs that good, and sing that well, was just sort of exactly what we wanted to do.

NOISEY: What are the key tracks on the record for you?

MIKE MILLS: “Jesus Christ” has always stuck with me. I recorded a version of that for an R.E.M. Christmas single. “O, Dana” has always stuck with me. They’re so oddly fragmented, some of these songs, it’s just the most amazing thing. Those are the ones that got me first.

NOISEY: What about the big, bleak set pieces like “Big Black Car” or “Kangaroo”?

MIKE MILLS: Those took me a couple of times. “Holocaust,” you know, those ones, they’re so harrowing, my natural, sunny disposition was kind of shocked by those and it took me a little while to let my guard down and actually explore those, but they’re among the most moving. MORE