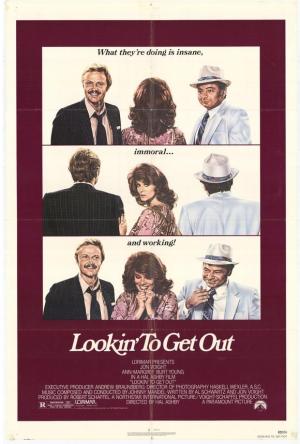

LOOKIN’ TO GET OUT (1982, directed by Hal Ashby, 120 minutes U.S.)

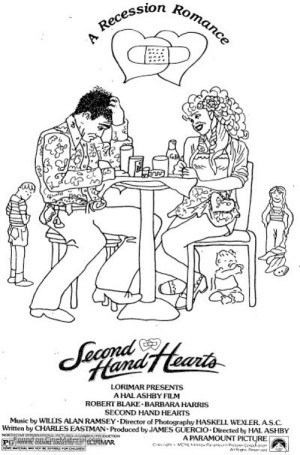

SECOND HAND HEART (aka THE HAMSTER OF LOVE) (1981, directed by Hal Ashby, 102 minutes, U.S.)

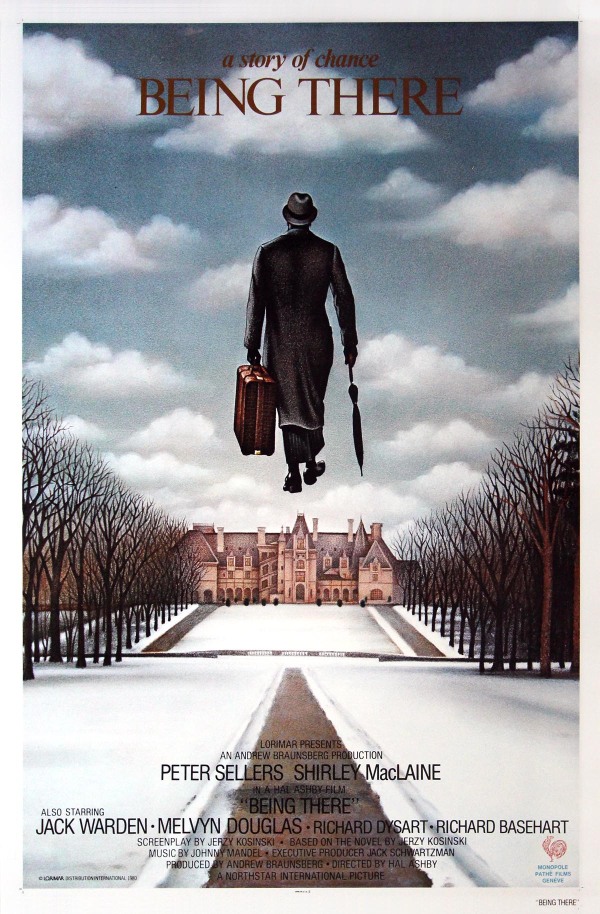

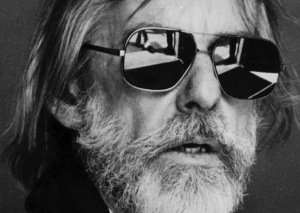

BY DAN BUSKIRK FILM CRITIC In Easy Riders, Raging Bulls, Peter Biskind’s popular tome about American film in the 1970s, Hal Ashby is held up as the quintessential director of his era. Ashby specialized in humanistic tales of outcasts looking for love and struggling to find their place in the world and the seven films he made between 1970 and 1979 make for an unusually rich and diverse body of work, everything from dark-humored fables like Harold & Maude and Being There to direct, politically-minded social dramas like Coming Home and his debut The Landlord.

Ashby would go on to direct four more features before his death at the age of 59 in 1988. They each were badly-reviewed and the gossip mill at the time blamed it (perhaps unfairly according to his biographer, Nick Dawson, author of the sturdy bio Being Hal Ashby) on Ashby’s increasing drug use. I’d make a case that 1982’s Lookin’ to Get Out and to a lesser extent 1981’s Second Hand Hearts are most worthy of reevaluation, both bearing the unmistakable earmarks of the iconoclastic cinematic master.

the gossip mill at the time blamed it (perhaps unfairly according to his biographer, Nick Dawson, author of the sturdy bio Being Hal Ashby) on Ashby’s increasing drug use. I’d make a case that 1982’s Lookin’ to Get Out and to a lesser extent 1981’s Second Hand Hearts are most worthy of reevaluation, both bearing the unmistakable earmarks of the iconoclastic cinematic master.

After winning an Oscar with Ashby for Coming Home, actor Jon Voight was anxious to work with the director again. Voight brought Ashby a script written by himself and an old family friend, rock manager Al Schwartz, who based the story of con men carousing in a casino on times Schwartz spent with actor Joe Turkel. Voight chose as his co-star the swarthy, simian Burt Young, best-known as the lovable slob “Paulie” from the Rocky series. The production was given full-access to Las Vegas’ MGM Grand Hotel (documenting its early 80’s dazzle just days before a tragic fire destroyed its lobby and killed 85 people) as a sprawling modern landscape for Voight and Young’s continuously collapsing con. Ashby fell in love with the music of The Police at the time (well, it was the 80’s) and wanted to use music from the band’s first three albums to propel the film’s momentum but ending up using composer Johnny Mandel to craft a recognizably Police-like approximation.

Voight’s 40-ish, manic, compulsive character feels like a gambler for whom time has run out and with the creeping corporatism of the 1980’s, this definitive 70’s director’s time had run out as well. Entangled in post-production conflict with the producers at Lorimar Pictures, Ashby left the editing process to the studio, who made extensive cuts to the film, unloading 15 minutes by taking out bits and pieces of nearly every scene, dramatically altering the rhythms of the film. Lookin’ to Get Out eventually opened to mixed reviews and meager box office and after an early VHS release and a brief cable run, basically disappeared from interest.

In 2007, Ashby biographer Nick Dawson made a major discovery when noticing that there were two film prints of Lookin’ to Get Out in the UCLA archive and one was a reel longer than the other. The print turned out to be Ashby’s completed edit (Ashby began his career as an Oscar-winning editor) and the difference was astounding. Recently comparing this new edit to a VHS tape buried deep in my personal collection was a real eye-opener about the art of editing. Although nearly every scene remains in the shorter release cut, they basically truncated each scenes’ build up, which particularly makes Voight’s  compulsive character more manic and less recognizably human. The narrative’s main beats are all present but instead of unfolding in front of you, they are thrust in the viewers’ faces. Also, few characters are given speaking roles in an Ashby film without revealing something about themselves, either with a snippet of dialogue or a subtle bit of action but the theatrical version saw this as fine fat for the trimming. Where the release version had fleeting, Ashby-esque moments, this newly restored version feels like an Ashby film through and through. This edit doesn’t just properly frame Voight’s performance, it’s a deep pleasure to see Burt Young stretch out in a rare co-starring role, showing a depth, range and watchability of which his character roles always hinted. Ann-Margret gives her best performance of the era, her often-silent concern carries an extra weariness at this age as she quietly defines the moral center of the film.

compulsive character more manic and less recognizably human. The narrative’s main beats are all present but instead of unfolding in front of you, they are thrust in the viewers’ faces. Also, few characters are given speaking roles in an Ashby film without revealing something about themselves, either with a snippet of dialogue or a subtle bit of action but the theatrical version saw this as fine fat for the trimming. Where the release version had fleeting, Ashby-esque moments, this newly restored version feels like an Ashby film through and through. This edit doesn’t just properly frame Voight’s performance, it’s a deep pleasure to see Burt Young stretch out in a rare co-starring role, showing a depth, range and watchability of which his character roles always hinted. Ann-Margret gives her best performance of the era, her often-silent concern carries an extra weariness at this age as she quietly defines the moral center of the film.

Despite the added length, the pacing of the scenes gives the film a momentum it didn’t have before. The cons deepen and deepen until a thrillingly tense, masterfully-edited showdown at the blackjack tables (featuring beloved character actor Bert Remsen in one of his juiciest roles) that even the theatrical cut didn’t dare touch. The only thing that can top the well-mounted climax is a brief final scene that gives us Voight’s daughter Angelina Jolie in her film debut at the age of six. While not as conceptually daring as Ashby’s earlier masterpieces, the director’s cut of Looking to Get Out is the highly entertaining work of a master in complete control of his craft.

– – – – – – – –

Fittingly the second on the bill, Second Hand Hearts (originally titled “The Hamster of Love”) does not display such consistent mastery but it is one of those undisciplined films that reveal as much about a director as their triumphs. Shot between two career highpoints, (the post-Vietnam drama Coming Home and the Peter Sellers tour-de-force, Being There), Second Hand Hearts fulfilled Ashby’s long-standing dream to make a film from the pen of screenwriter Charles Eastman. Eastman was the brother of esteemed screenwriter Carole Eastman (writer of Five Easy Pieces) and a renowned script doctor, with his ’60’s script Honeybear, I Think I Love You having a reputation in Hollywood circles as being the greatest unfilmed script of its time.

The script came with actor Robert Blake attached, a mercurial talent whose career went back to his childhood in the 1940’s, where he worked with Bogart as well as in the Our Gang series. Here, in what Ashby termed “A Recession Romance,” Blake plays Loyal Mukes a recently fired car wash attendant who in the opening learns that he married a bar band sincerely daffy vocalist Dinette Dusty (Barbara Harris, the mother in the original Freaky Friday). Leery of his newfound matrimonial state, the anxious Loyal hits the road in a dilapidated station wagon to pick up Dinette’s trio of children from the in-laws of her dead husband and head west with his new family to the promised land of California.

Ashby edited and re-edited Second Hand Hearts but felt for the first time his deft touch could not bring the patient back to life. The shooting had been a disaster, with the desert roads outside El Paso during June and September being soul-crushingly hot. Harris and Blake reportedly did not get along, with Blake willingly improvising up a storm while Harris would decide on a line reading and stick to it. The characters are the least exceptional and perhaps most desperate of any  of Ashby’s oddball couples, with death, suicide, rape and complete destitution cutting way deeper than the comic asides can bear, as we watch the precarious new family suck up the dust on their eventful little road trip.

of Ashby’s oddball couples, with death, suicide, rape and complete destitution cutting way deeper than the comic asides can bear, as we watch the precarious new family suck up the dust on their eventful little road trip.

Once finished, the film was abhorred by the studio execs at Lorimar. After a meek, barely-promoted opening in selected cities (I remember Blake begging the audience on Carson’s The Tonight Show to seek the film out) Second Hand Hearts played a brief run on HBO and was seemingly sent to dead movie purgatory (it never even found a home video release until Warner’s On-Demand service revived the film).

While all the film’s Ashby elements fail to gel nearly from the outset, Second Hand Hearts audaciousness, especially in the near-surreal second half, give the more perverse filmhound much to savor. First, the striking desert landscape and its dusty near-ghost towns are gorgeously filmed by Haskell Wexler, the Hollywood legend who directed Medium Cool and shot iconic films like Cuckoo’s Nest, The Conversation and the original Thomas Crown Affair, and his work is as brilliant as ever (that goes for his work in Lookin’ to Get Out as well). Bert Remsen is again on hand as Dinette’s exhausted father-in-law and Shirley Stoler, the large-framed woman from the cult classic The Honeymoon Killers has a casually shocking turn as a seen-it-all desert dweller.

The film reminds me of Coppola’s One From the Heart, a similarly ambitious and unsuccessful romantic fable released in 1982, featuring screwed-up kids bearing the metaphorically-weighted names Human, Iota and Sandra Dee. Second Hand Hearts‘ glowing sunset-drenched climax reaches for a manic, ecstatic optimism one would find in the musicals of the Depression-era. As bleak as the family’s options are, the viewer can’t quite buy the euphoric release and I’m not convinced Ashby does either. It’s as if Ashby’s fervent, ’60s-inspired counter-cultural humanism has calcified into a Reaganite fake smile of populist good cheer.

The rest of the decade left Ashby out to dry. He directed two more features, both released in 1985: an oblong action film with Jeff Bridges and Andy Garcia called Eight Million Ways to Die and a benign, faceless Neil Simon romantic comedy, The Slugger’s Wife. He left the editing of both films to the studio and Ashby’s hand is felt only fleetingly throughout. Robert Altman, another definitive ’70s director floundered similarly in the era before finding his feet and one suspects Ashby might have as well if he didn’t died of pancreatic cancer in 1988. But with Lookin’ to Get Out and Second Hand Hearts we get the last unexpurgated taste of pure Ashby, an artist who loved and campaigned tirelessly for his shaggy, shambolic characters’ humanity until Hollywood would let him love us no more.