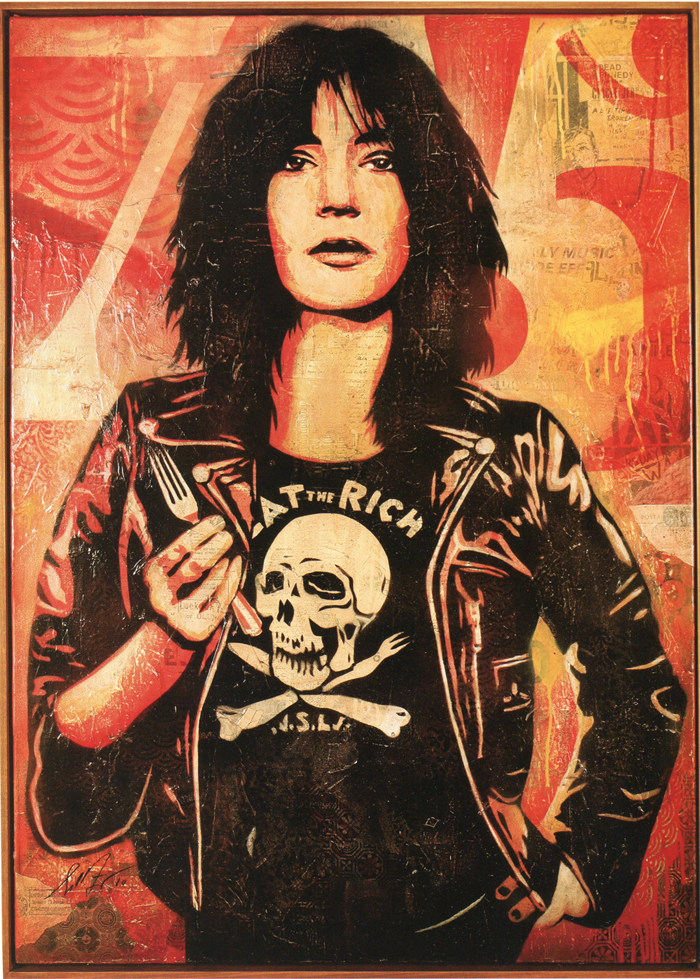

Illustrations by SHEPARD FAIREY

BY MEGAN MATUZAK Patti Smith is a world renowned poet, painter and musician — the high priestess of punk, to be exact — but lately she’s been making her bones as a highly regarded memoirist. Her 2010 memoir, Just Kids, a coming-of-age chronicle of her time in New York City with artist Robert Mapplethorpe in the ‘60s and ‘70s, sold more than a half million copies and won a National Book Award. Her latest, M Train, is one part memoir, one part benediction and one part Homeric odyssey cataloging Smith’s “vagabondia,” a term of art for traveling from place to place without a true sense of home. “All writers are bums, may I be counted among you one day,” she says, toasting the lionized Japanese novelist Osamu Dazai after visiting his grave.

BY MEGAN MATUZAK Patti Smith is a world renowned poet, painter and musician — the high priestess of punk, to be exact — but lately she’s been making her bones as a highly regarded memoirist. Her 2010 memoir, Just Kids, a coming-of-age chronicle of her time in New York City with artist Robert Mapplethorpe in the ‘60s and ‘70s, sold more than a half million copies and won a National Book Award. Her latest, M Train, is one part memoir, one part benediction and one part Homeric odyssey cataloging Smith’s “vagabondia,” a term of art for traveling from place to place without a true sense of home. “All writers are bums, may I be counted among you one day,” she says, toasting the lionized Japanese novelist Osamu Dazai after visiting his grave.

In M Train, Smith maps out the landmarks of her life spanning the late ‘80s to the present, a whirlwind tour of bohemian cafe’s, graves of idolized writers, writer’s conferences, memories of her children and her dearly departed husband Fred “Sonic” Smith, guitarist for The MC5, who passed away suddenly in 1994 at the age of 45. Smith starts out on her journey without a plotted course, no map or compass, or even a fixed timeline — one chapter extracts memories from five years ago, the next chapter revisits memories from 15 years ago. Each memory is a psychic touchstone revisited with reverence and prayers, and never ending cups of coffee, notebooks, dungarees and Polaroids.

To write M Train Smith settled into a routine, every morning the same table, the same order at the same place: black coffee and bread with olive oil at Cafe ‘Ino. Smith relies on  routine to create order amidst the chaos of constant traveling and performing. It’s through the creation of habits and routine that she validates her own existence to herself. More importantly, these routines act as a souvenir of her attempts at normality.

routine to create order amidst the chaos of constant traveling and performing. It’s through the creation of habits and routine that she validates her own existence to herself. More importantly, these routines act as a souvenir of her attempts at normality.

In the first chapter, Smith travels back to a time early in her marriage to Fred. Inspired by poet and playwright Jean Genet, she proposes a pilgrimage to Saint-Laurent-du-Maroni prison in French Guiana as their last hurrah before childbearing. Genet, an unrepentant thief in his youth, and no stranger to the inside of a jail cell, wrote about the prison in The Thief’s Journal. The prison was notorious for its abominable living conditions. Though he never actually did time at Saint-Laurent-du-Maroni, Genet was fascinated by it and wrote about how he aspired to experience “the grandeur” he imagined to exist within the walls of the prison and expose it to the world. But Genet never made it to Saint-Laurent-du-Maroni, much to his dismay. “I am shorn of my infamy,” he wrote.

Smith set out to restore Genet’s infamy in her own way. In a small Gitanes matchbox, Smith stores some stones from a cell in the prison and saves them for over two decades, unable to put the souvenier into the hands of Genet himself, who passed away in 1986, as she had originally planned. In a chapter much later in the book titled “Road to Larache,” Smith finally travels to his grave. “I said the words I wished to say, then poured water upon the ground and dug deep, inserting the stones. As we laid our flowers we could hear the distant sound of the muezzin calling people to prayer.”

M Train is full of pilgrimages to graves and memorials such as Sylvia Plath’s headstone in Heptonstall in the U.K. and a conference in Berlin marking the 125th anniversary of the death of German geophysicist Alfred Wegener. Wegener, the “pioneer of the continental drift” theory, was so dedicated to his work as a scientist that he disappeared in Greenland while trying to prove his hypothesis. Smith reveres and identifies with writers, artists and thinkers who get lost in the intensity of the their devotion to their work.

In the chapter “Wheel of Fortune,” Smith is invited to deliver a speech at the home-turned-museum of the Frida Kahlo, who ranks high in Smith’s pantheon of the greats. Sick as a dog, Smith spent her visit writing a song for the occasion while convalescing in the very same bed a sickly Kahlo shared with her husband Diego Rivera. Later she performed the song at the conclusion of her speech in the courtyard of the Kahlo estate, reducing everyone to tears. At the bar after the speech and a few sips of tequila, Smith finally name drops the title, “I closed my eyes and saw a green train with an M in a circle; a faded green like the back of a praying mantis.” The M train is a subway line that stops near Smith’s home in Brooklyn.

In the end, M Train is all about the search for closure, about completing circles and making peace with your ghosts as you prepare to enter the winter of your life. “I have lived in my own book,” Smith writes in M Train, “one I never planned to write, recording time backwards and forwards. I have watched the snow fall onto the sea and traced the stops of a traveler long gone. I have relived moments that were perfect in their certainty.”

One of those moments of perfect certainty happened to Smith a couple weeks ago during a reading of M Train at Dominican University in Illinois. According to news reports, midway through the reading a woman stood up and informed Smith that the backpack she had in her hands belonged to her. The backpack was among the items stolen from her tour van back in 1979. The contents of the backpack included two totems of infinite sentimental value: a 1978 Rolling Stones shirt Fred was often photographed in, and a bandana that had belonged to her brother Todd, who died one month after Fred’s funeral in 1994. There wasn’t a dry eye in the house as Smith, tears running down her cheeks, explained to the audience why these seemingly everyday objects had, in the fullness of time, become holy relics to her.

PATTI SMITH WILL DISCUSSING M TRAIN @ THE FREE LIBRARY ON NOV. 6TH