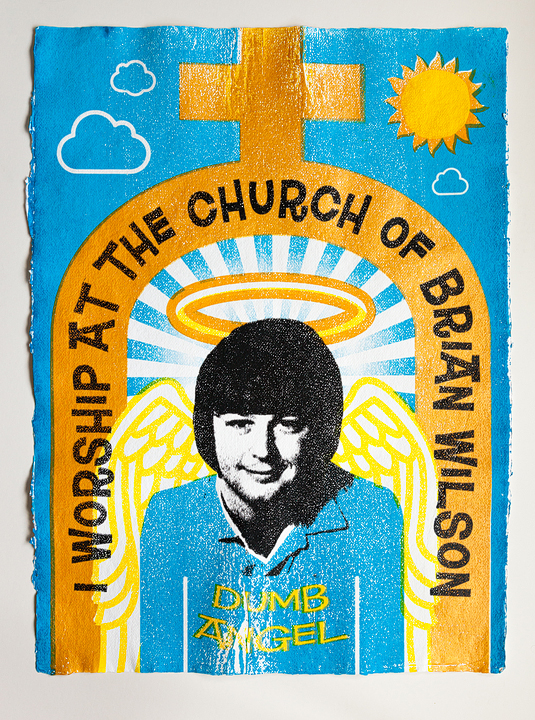

SLATE: Smile, the Beach Boys’ famously scrapped project, is the most celebrated album never made. Recorded in late 1966 and early 1967 on the heels of the critically lauded album Pet Sounds and the follow-up smash single “Good Vibrations,” Smile was being billed as a significant turning point in popular music well before the public had heard a single note of it. One of the album’s earliest champions was the writer Jules Siegel, whose magazine, the Saturday Evening Post, had commissioned him to write an article on its making. Siegel, blown away by what he heard during his interviews with Wilson, turned in a rhapsodic profile; the Post chided him for abandoning his journalistic objectivity and summarily killed it. Upon hearing one song being readied for the album, the coyly titled epic “Surfs Up,” Leonard Bernstein described it as “too complex to get all of the first time around … poetic, beautiful, even in its obscurity.” By  this point, Wilson had taken to calling Smile his “teenage symphony to God” and gamely (mis)quoting the American psychiatric pioneer Karl Menninger, signifying that in the four short years since the Beach Boys had risen to the top of the charts with carefree anthems like “Surfin’ Safari,” Wilson had finally and permanently abandoned the tropes of fun in favor of something far more complicated. In doing so, he had safely guided the Beach Boys out of the square wilderness into the realm of the hip—governed at the time by the Revolver-era John Lennon and Paul McCartney, who were said to be working on a new album that was even more daring.

this point, Wilson had taken to calling Smile his “teenage symphony to God” and gamely (mis)quoting the American psychiatric pioneer Karl Menninger, signifying that in the four short years since the Beach Boys had risen to the top of the charts with carefree anthems like “Surfin’ Safari,” Wilson had finally and permanently abandoned the tropes of fun in favor of something far more complicated. In doing so, he had safely guided the Beach Boys out of the square wilderness into the realm of the hip—governed at the time by the Revolver-era John Lennon and Paul McCartney, who were said to be working on a new album that was even more daring.

The story of how Smile came not to be has, over time, taken on the aura of parable: It’s the story of the emotionally fragile genius beset by knaves, forced to abandon his magnum opus rather than allow it to be compromised. In this oversimplified version of events, the heavy is usually played by Beach Boy Mike Love (Wilson’s cousin), who openly objected to the experimental, and arguably uncommercial, direction in which the group was apparently headed. A pivotal moment took place during the recording of ” Cabinessence,” when Love was asked to sing one of the more esoteric lines penned by Van Dyke Parks, a Los Angeles folk-scene wunderkind whom Wilson had hired to produce suitable lyrics. Parks’ elliptical, impressionistic poetry conjured a surreal vista punctuated by sturdy emblems of Americana: divine visitations, the building of the railroads, decadent opera-goers, Old West tableaux, agrarian idylls—more libretto than pop lyric. Love finally agreed to sing the line (“Over and over/ The crow cries, ‘Uncover the cornfield’ “) after an angry protest, but his vote of no-confidence alienated Parks, who ended up walking away from the project. Meanwhile, Wilson’s LSD-addled mood, already mercurial, hardened into a full-fledged bipolarity, marked by bursts of obsessive tweaking alternating with long periods of sulky inaction. He was acutely aware that with the release of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, the Beatles were about to lay irrefutable claim to the title of Pop’s Reigning Geniuses, and he was despondent at having lost the race to usher in the “new sound.” By the time Sgt. Pepper came out, it was already sadly evident that Smile probably never would. MORE

CHEETAH MAGAZINE, 1967: It was just another day of greatness at Gold Star Recording Studios on Santa Monica Boulevard in Hollywood. In the morning four long-haired kids had knocked out two hours of sound for a record plugger who was trying to curry favor with a disk jockey friend of theirs in San Jose. Nobody knew it at the moment, but out of that two hours there were about three minutes that would hit the top of the charts in a few weeks, and the record plugger, the disk jockey and the kids would all be hailed as geniuses, but geniuses with a very small g.

Now, however, in the very same studio a Genius with a very large capital G was going to produce a hit. There was no doubt it would be a hit because this Genius was Brian Wilson. In four years of recording for Capitol Records, he and his group, the Beach Boys, had made surfing music a national craze, sold 16 million singles and earned gold records for 10 of their 12 albums.

Not only was Brian going to produce a hit, but also, one gathered, he was going to show everybody in the music business exactly where it was at; and where it was at, it seemed, was that Brian Wilson was not merely a Genius—which is to say a steady commercial success—but rather, like Bob Dylan and John Lennon, a GENIUS—which is to say a steady commercial success and hip besides.

Until now, though, there were not too many hip people who would have considered Brian Wilson and the Beach Boys hip, even though he had produced one very hip record, “Good Vibrations,”  which had sold more than a million copies, and a super-hit album, Pet Sounds, which didn’t do very well at all—by previous Beach Boys sales standards. Among the hip people he was still on trial, and the question discussed earnestly among the recognized authorities on what is and what is not hip was whether or not Brian Wilson was hip, semi-hip or square.

which had sold more than a million copies, and a super-hit album, Pet Sounds, which didn’t do very well at all—by previous Beach Boys sales standards. Among the hip people he was still on trial, and the question discussed earnestly among the recognized authorities on what is and what is not hip was whether or not Brian Wilson was hip, semi-hip or square.

But walking into the control room with the answers to all questions such as this was Brian Wilson himself, wearing a competition-stripe surfer’s T-shirt, tight white duck pants, pale green bowling shoes and a red plastic fireman’s helmet. Everybody was wearing identical red plastic toy fireman’s helmets. Brian’s cousin and production assistant, Steve Korthoff was wearing one; his wife, Marilyn, and her sister, Diane Rovelle—Brian’s secretary—were also wearing them, and so was a once-dignified writer from The Saturday Evening Post who had been following Brian around for two months.

Out in the studio, the musicians for the session were unpacking their instruments. In sport shirts and slacks, they looked like insurance salesmen and used-car dealers, except for one blond female percussionist who might have been stamped out by a special machine that supplied plastic mannequin housewives for detergent commercials.

Controlled, a little bored after 20 years or so of nicely paid anonymity, these were the professionals of the popular music business, hired guns who did their jobs expertly and efficiently and then went home to the suburbs. If you wanted swing, they gave you swing. A little movie-track lushness? Fine, here comes movie-track lushness. Now it’s rock and roll? Perfect rock and roll, down the chute.

“Steve,” Brian called out, “where are the rest of those fire hats? I want everybody to wear fire hats.  We’ve really got to get into this thing.” Out to the Rolls-Royce went Steve and within a few minutes all of the musicians were wearing fire hats, silly grins beginning to crack their professional dignity.

We’ve really got to get into this thing.” Out to the Rolls-Royce went Steve and within a few minutes all of the musicians were wearing fire hats, silly grins beginning to crack their professional dignity.

“All right, let’s go,” said Brian. Then, using a variety of techniques ranging from vocal demonstration to actually playing the instruments, he taught each musician his part. A gigantic fire howled out of the massive studio speakers in a pounding crash of pictorial music that summoned up visions of roaring, windstorm flames, falling timbers, mournful sirens and sweating firemen, building into a peak and crackling off into fading embers as a single drum turned into a collapsing wall and the fire-engine cellos dissolved and disappeared.

“When did he write this?” asked an astonished pop music producer who had wandered into the studio. “This is really fantastic! Man, this is unbelievable! How long has he been working on it?”

“About an hour,” answered one of Brian’s friends.

“I don’t believe it. I just can’t believe what I’m hearing,” said the producer and fell into a stone glazed silence as the fire music began again.

For the next three hours, Brian Wilson recorded and re-recorded, take after take, changing the sound balance, adding echo, experimenting with a sound effects track of a real fire.

“Let me hear that again.” “Drums, I think you’re a little slow in that last part. Let’s get right on it.” “That was really good. Now, one more time, the whole thing.” “All right, let me hear the cellos alone.” “Great. Really great. Now let’s do it!”

With 23 takes on tape and the entire operation responding to his touch like the black knobs on the control board, sweat glistening down his long, reddish hair onto his freckled face, the control room a litter of dead cigarette butts, Chicken Delight boxes, crumpled napkins, Coke bottles and all the accumulated trash of the physical end of the creative process, Brian stood at the board as the four speakers blasted the music into the room.

For the 24th time, the drum crashed and the sound effects crackle faded and stopped.

“Thank you,” said Brian into the control room mic. “Let me hear that back.” Feet shifting, his body still, eyes closed, head moving seal-like to his music, he stood under the speakers and listened. “Let me hear that one more time.” Again the fire roared. “Everybody come out and listen to this,” Brian said to the musicians. They came into the room and listened to what they had made.

“What do you think?” Brian asked.

“It’s incredible, incredible,” whispered one of the musicians, a man in his fifties wearing a Hawaiian shirt and iridescent trousers and pointed black Italian shoes. “Absolutely incredible.”

“Yeah,” said Brian on the way home, an acetate trial copy or “dub” of the tape in his hands, the red plastic fire helmet still on his head. “Yeah, I’m going to call this ‘Mrs. O’Leary’s Fire’ and I think it might just scare a whole lot of people.”

As it turns out, however, Brian Wilson’s magic fire music is not going to scare anybody—because nobody other than the few people who heard it in the studio will ever get to listen to it. A few days after the record was finished, a building across the street from the studio burned down and, according to Brian, there was also an unusually large number of fires in Los Angeles. Afraid that his music might in fact turn out to be magic fire music, Wilson destroyed the master. MORE

JULES SIEGEL: Although Turrentine correctly reports that the Saturday Evening Post killed my story, it was later published  in Cheetah magazine, October, 1967, as “Goodbye Surfing, Hello God!–the Religious Conversion of the Beach Boys.” It’s been anthologized in at least four books, most recently in Library of America’s Writing Los Angeles.

in Cheetah magazine, October, 1967, as “Goodbye Surfing, Hello God!–the Religious Conversion of the Beach Boys.” It’s been anthologized in at least four books, most recently in Library of America’s Writing Los Angeles.

Without any false humility, I can say that I was one of the people who invented rock journalism. Journalists such as Al Aronowitz, Richard Goldstein and I were among the first to write about rock in mainstream media without being condescending or demeaning. Nonetheless, I never thought of “Goodbye Surfing, Hello God!” as rock journalism. It was a pretty far-out piece even for regular journalism at the time. I don’t think many celebrity pieces before or since have ever gotten that close to a subject and been written about it.

Brian was quite upset about it. I heard that the Beach Boys were still complaining about it a few years later in Tom Nolan’s Rolling Stone interview. Maybe now he’s got some more distance on it and can see that “Goodbye Surfing, Hello God!” was a principal force in creating the myth of Smile. I know that others did write about it at the time, but some of them talked to me first. Other than David Oppenheimer, I was the only one in the major media who took Brian seriously, and even David talked with me at great length while he was making his documentary.

In reading over my story 37 years later, I see some rather awkward moments. At the time, Saturday Evening Post writers did not usually mention themselves in stories. I wanted to do this story exactly as I would have written a short story or a segment of a novel. In order to get around my adherence to the convention of impersonality, I had to describe myself as a “Saturday Evening Post writer” and a “friend.” Both were true, but these days I would just use “I” or “me.” Some of the writing is a little too self-consciously jazzy, but I was young then.

Despite these minor flaws, I’m still very happy with the story, and I am even happier that Brian has finally achieved his dream. He was a giant then and he is a giant now. All of us who struggle against the mainstream currents can take heart in this outcome. For once, a good guy wins. God bless Brian Wilson! God bless all artists who try and fail, and try again and fail again, ad infinitum, but never give up. MORE