![]() BY DAN BUSKIRK FILM CRITIC If the state of the world tends to shade your personal mood, it is pretty easy to consider 2014 a year of epic trauma and bad vibes. I was thinking it was an off year for film too but when I went over my notes it turns out there was a lot to be enthusiastic about, although we again seem to be thirsting for truly original American cinema this year. Here’s a baker’s dozen films that took me to new places, many of them seeming like they could be made in no other time than the tumultuous, unnerving year of 2014.

BY DAN BUSKIRK FILM CRITIC If the state of the world tends to shade your personal mood, it is pretty easy to consider 2014 a year of epic trauma and bad vibes. I was thinking it was an off year for film too but when I went over my notes it turns out there was a lot to be enthusiastic about, although we again seem to be thirsting for truly original American cinema this year. Here’s a baker’s dozen films that took me to new places, many of them seeming like they could be made in no other time than the tumultuous, unnerving year of 2014.

For me and at least a few friends, everything this year paled beside Alejandro Jodorowsky’s improbable comeback The Dance of the Reality. How has this film escaped so many critical year-end lists? The maker of cult epics El Topo and The Holy Mountain returns with a surreal autobiographical story that tames his wild digressions in order to refine its emotional impact. The tale concerns his childhood with his Jewish mother and father in Chile but it is the way Jodorowsky transforms his formative experiences with metaphor, poetry and myth that makes it a wholly unique work whose ever-blossoming imagination leaves the rest of this year’s films in the dust. The 2014 release of the documentary Jodorowsky’s Dune, chronicling the director’s thwarted production of Frank Herbert’s sci-fi classic, only deepened the richness of The Dance of Realty, further illuminating the visionary 85 year-old director’s talent and reputation.

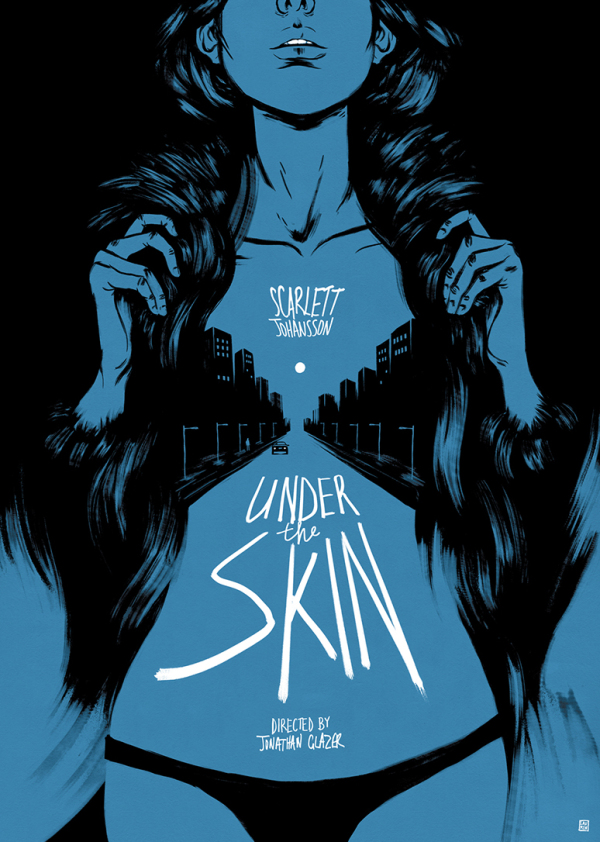

Under The Skin was another film whose joys were amplified by another release; in this case, Luc Besson’s Lucy which also featured Scarlett Johansson in an otherworldly state. Under the Skin didn’t have the pop action punch of Lucy but instead  lingered in a narcotized dream state, following the unearthly Johansson as she sucked the life out of hapless would-be suitors like a diligent alien praying mantis. Director Jonathan Glazer has shown an acute visual style in past dramas Sexy Beast and Birth but those very literal films left me completely unprepared for his gorgeously abstract and intuitive work here.

lingered in a narcotized dream state, following the unearthly Johansson as she sucked the life out of hapless would-be suitors like a diligent alien praying mantis. Director Jonathan Glazer has shown an acute visual style in past dramas Sexy Beast and Birth but those very literal films left me completely unprepared for his gorgeously abstract and intuitive work here.

Another woman’s tale that dips a little more lightly into surrealism is Tim Burton’s Big Eyes, which similar to his 2003 Big Fish found the director making time to insert a little honest emotion into his weird yarn. A 20th century feminist tale, Big Eyes follows the miserably married Keane couple, where Margaret (dependably wonderful Amy Adams) does all the labor painting her sad-eyed waifs while husband Walter (endlessly villainous Christof Waltz) takes all the acclaim. Of course she battles back but it is the portrait of Margaret’s own sad eyes as she’s captured in that glassy modernist home that lingers in the memory.

Nymphomaniac sounds almost too obvious for the title of a Lars Von Trier provocation but the film’s focus on one woman’s sexual autobiography underlines just how absurdly chaste are American films. Charlotte Gainsbourg and Stacy Martin share the role of Joe, confessing her story to the impotent Seligman. (Stellan Skarsgård) Joe is a sexual adventurer, willing to break boundaries to explore all dimensions of Eros. Like a private eye film, its the people we meet along the way that makes Von Trier’s latest so engaging, with Willem Defoe, Udo Kier and Jaime Bell (Billy Elliot himself!) taking turns showing their freaky sides. There is lots of titillation to enjoy along the way but ultimately it was Von Trier’s ideas about storytelling and personal mythmaking that gave Nymphomaniac a kick beyond pure voyeurism.

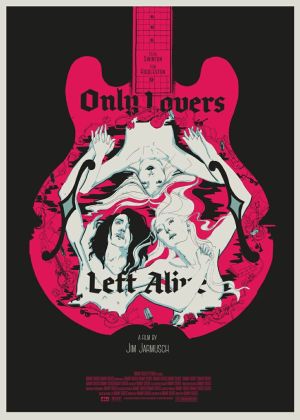

I’d written off Jim Jarmusch as a prisoner of his own quirks for much of his career but The Only Lovers Left Alive peeled away his usual tone of hipster reserve. Tom Hiddleston and Tilda Swinton make for a most romantic couple of vampires. Getting their blood the dignified way, through the back door of blood banks, the pair spend their eternal lives making music and studying science and literature in a state of low-key antique elegance. It all looked a lot like the life of leisure a successful artist like Jarmusch himself might live, giving the film a personal warmth missing in much of his work.

I’d written off Jim Jarmusch as a prisoner of his own quirks for much of his career but The Only Lovers Left Alive peeled away his usual tone of hipster reserve. Tom Hiddleston and Tilda Swinton make for a most romantic couple of vampires. Getting their blood the dignified way, through the back door of blood banks, the pair spend their eternal lives making music and studying science and literature in a state of low-key antique elegance. It all looked a lot like the life of leisure a successful artist like Jarmusch himself might live, giving the film a personal warmth missing in much of his work.

Lenny Abramson’s Frank was about music-making as well, with a group of musicians holed up in rural Ireland while their leader Frank inspires them to record his masterpiece. Most rock bands are fronted by stubborn personalities; this band is led by a fellow who never takes off his giant paper-mâché head. Are there issues under that head? You bet. Frank was co-written by musician Jon Ronson and few films so accurately capture the delusional spirit so often a part of being in a rock band and the film’s unsettled ending is bravely true to the story’s realities when an upbeat finale would have been easy to give in to.

Iranian director Asghar Farhadi’s The Past (a 2013 film that didn’t hit Philly till late January 2014) made a fascinating mystery out of the quiet domestic discord in a Parisian family. Ahmad (a soulful Ali Mosaffa) returns to sign his divorce papers and finds that he is the only one who can heal the wounds of his former ragtag household. Farhadi’s intricately-wrought script shows how each family member holds a piece of the puzzle while not knowing their own place in its frame. Masterful storytelling with a special wisdom on family life.

I found Bennett Miller’s true crime tale Foxcatcher completely mesmerizing. A depiction of the 1996 murder of Olympic wrestler Dave Schultz by an heir of the Dupont fortune, the story gave Miller a chance to demonstrate his ability to thrust us deeply into a sad and privileged world. Channing Tatum and Mark Ruffalo completely inhabited the physical worlds of the wrestling Schultz brothers and Steve Carrell’s wealth-addled  Dupont captured a scary blankness that was deeply disturbing. Miller’s last two features, Capote and Moneyball were very impressive but Foxcatcher‘s eerie gravity puts his latest work in a whole different league.

Dupont captured a scary blankness that was deeply disturbing. Miller’s last two features, Capote and Moneyball were very impressive but Foxcatcher‘s eerie gravity puts his latest work in a whole different league.

Murder was at the center of Jeremy Saulnier’s vivid thriller Blue Ruin. Unknown actor Macon Blair plays Dwight, a homeless drifter who snaps to life as he plans revenge on a just-released ex-con. If the story’s facts were laid out in a newspaper article it would seem like a mundane violent crime but Saulnier miraculously re-images the events with a modern sense of reality unseen in Hollywood film. Beneath its tense violent thrills is a commentary on our vigilante fantasies, how the idea of a cleansing violent act quickly turns messy once introduced into the complicated “real” world.

J.C. Chandor’s A Most Violent Year is a similarly gritty but not without a Hollywood gloss. It is applied in such an inyelligent manner to show that doesn’t have to be a bad thing. Set in the early 80s, the story is super-charged by the performance of Oscar Isaac, (star of Inside Llewyn Davis) whose smoldering performance I can only assume is drawing comparisons to the young Pacino. Here Isaac is Abel Morales, an up-and-coming man in the North Jersey heating oil business who find his big deal endangered by a string of robberies of his oil trucks. Chandor captures all the vivid details we loved in the landscape of The Sopranos with a spot-on cast that brings to life every tense scene. And I love a crime story with an extra-smart finale that actually deepens rather than nullifies its preceding tale.

I’m amongst the vocal group that thinks the best blockbuster of the summer wasn’t from Hollywood but South Korea, being an unapologetic lover of Boon-Joon Ho’s post-apocalyptic train story, Snowpiercer. In his world, power and revolution are neatly laid out in descending train cars as the wealthy live closest to the engine and the smudgy lower classes toil in the wealthy’s bilge water at the train’s end. Living in a time of record wealth disparity, this concise little allegory took on an extra emotional heft. But Boon-Jon Ho’s (who previously made the striking features The Host and Mother) script doesn’t idealize revolution allowing an ambiguity that adds a richness to its first-rate blockbuster thrills.

Laura Poitras’ Citizenfour is a film set in our dystopic present, detailing how whistleblower Eric Snowden first released the classified documents that revealed the extent of our government’s surveillance program. Mainly shot in the sterile environs of a Honk Kong hotel, the documentary plays like a no-budget Smart phone-shot paranoid thriller, showing the insane lengths taken by Snowden and journalists Poiutras, Glenn Greenwald and Ewen MacAskill.of the Guardian in order to communicate beyond the U.S government’s purview. I’ve enjoyed endless permutations of the spy thriller across cinema histroy but CitizenFour carries a unique punch in showing that in the government’s eyes, the enemy is us.

Laura Poitras’ Citizenfour is a film set in our dystopic present, detailing how whistleblower Eric Snowden first released the classified documents that revealed the extent of our government’s surveillance program. Mainly shot in the sterile environs of a Honk Kong hotel, the documentary plays like a no-budget Smart phone-shot paranoid thriller, showing the insane lengths taken by Snowden and journalists Poiutras, Glenn Greenwald and Ewen MacAskill.of the Guardian in order to communicate beyond the U.S government’s purview. I’ve enjoyed endless permutations of the spy thriller across cinema histroy but CitizenFour carries a unique punch in showing that in the government’s eyes, the enemy is us.

Miyazaki’s final film The Wind Rises was a fitting valedictory, a tribute to hard work, imagination, and child-like wonder, a theme present in all of his work. A fictionalized biopic of aviation pioneer Jiro Horikoshi, Miyazaki details how tirelessness is a crucial element in creativity. The designer’s dreams are the film’s most memorable moments, as Jiro walks down the wings of planes in mid-flight discussing aerodynamics with his Italian aviatrix idol. Miyazaki doesn’t minimize the cruel paradox that Jiro’s love of flight is going to be put to use in war, but he leads us to believe it is the desire to keep dreaming that is the important thing.

I’m still kicking myself over titles that have slipped me by this year (I’m aching to see Godard’s 3-D film Goodbye to Language) yet as the years progress my exploration of cinema is always headed in both directions, backward and forward. As someone who grew up discovering film when commercial TV and the neighborhood theater were the only outlets, it continues to be dizzying to live in a time when nearly every surviving film from across the last one hundred years is available. The highlight of my film week is often a title I’ve waited literally decades to watch like animator Ralph Bakshi’s audacious South of the South parody, Coonskin or Dorothy Arzner’s 1940’s film Dance Girl Dance with a sex kittenish turn by Lucille Ball. My year would have been much less fulfilling without The I-House’s screening of Robert Altman’s 1969 psychodrama One Cold Day in the Park, Exhumed Film’s resurrection of the strangely potent 1979 time capsule Skatetown USA, finally sitting down with Kobayashi’s nearly two-hour pacifist war epic The Human Condition, Shintaro Katsu’s series of Blind Swordsman films, and Larry Yust’s West-Philly-shot 70s crime film Trick Baby at the PhilaMoca. Goodbye ’14, there’s a New Year already a-flickering…