“Saint Francis” by WALT LINDEVELD

BY JONATHAN VALANIA A word of warning: This is gonna be one of those pieces where I go on and on about my little monkey shines with famous alt-rock personalities. Millions of people love it when I do that, but others seem to get very, very angry about it, stomp their feet and write mean letters that hurt my feelings. If that sounds like you, stop reading right now. I’m serious. I don’t want to even see you in the second paragraph.

Set the Wayback Machine to 1988. I’m a college DJ stranded in the middle of Pennsyltucky. Entranced by the naked boob on the cover of Surfer Rosa, I slap it on the turntable and…they had me by the first 20 seconds of “Where Is My Mind?” and never really let go. Shortly thereafter I got a gig working for a Pennsyltucky daily. They asked me one day if I wanted to interview some guy named Black Francis from the Pixies. Would I? Man, this was a dream come true! I could finally learn the WTF of lyrics like, “He bought me a soda, he bought me a soda/ And he tried to molest me in the parking lot.”

When I got him on the phone, he was no doubt bone-tired from endless touring and weary of answering stupid  fanboy questions. He insisted I call him Charles and pretty much refused to give me a straight answer to any question. “Who cares?” he’d say. “We just try to make cool rock music.” I remember thinking: what a dick.

fanboy questions. He insisted I call him Charles and pretty much refused to give me a straight answer to any question. “Who cares?” he’d say. “We just try to make cool rock music.” I remember thinking: what a dick.

The next Pixie I met was Kim Deal, around 1994. The Breeders had just broken huge, and somebody had given Kim’s sister Kelley a copy of my band the Psyclone Rangers‘ debut album. Kelley listed one of the songs as one of her 10 favorites that year in Rolling Stone’s end-of-the-year wrap-up.

So I get her on the phone and we hit it off, and she invites me and the band to come hang out backstage at the Philly stop of Lollapalooza. I don’t remember much except it was hot and muddy and famous back there. The Psyclone Rangers were about to record our next album down in Memphis. We had a song we wanted that patented Deal-sister vocal on, and Kelley quickly agreed to sing on it. The night before she was supposed to fly down she called to say she was too sick to leave town. She sounded pretty out of it. Boy, were we bummed. Was it something we said or did? A few days later, when she got busted for receiving a FedEx envelope full of heroin, we put two and two together.

Fast-forward a year. The Psyclone Rangers are in L.A. playing a special pre-album-release club show for all the music-biz poohbahs. The kid who ran our label always bragged he was friends with Pixies guitarist Joey Santiago and drummer Dave Lovering. Yeah, right! Prove it, we’d always say. That night he did. Apres-gig we’re sitting backstage, and who walks in but the guitar player and the drummer from the Pixies, all smiles and compliments. The Pixies had long since split by then, and Santiago had formed a then-trendy cocktail act called the Martinis. To be honest, it was kind of a letdown: The guys from the Pixies don’t have anything better to do than hang out with chumps like us?

Fast forward a decade. Following Nirvana’s sincerest form of flattery and inspired theft, an entire generation of commercial alt-rock hits built on the Pixies patented song-writing template of lulling verses and volcanic choruses are already in the Where Are They Now? file. Black Francis has become Frank Black, releasing a steady string of increasingly irrelevant solo albums. The Breeders career went up the nose and in the arm of the Deal sisters. The Pixies guitarist went MIA into domesticity and the drummer gave up music to become…wait for it…a magician.

Fast forward a decade. Following Nirvana’s sincerest form of flattery and inspired theft, an entire generation of commercial alt-rock hits built on the Pixies patented song-writing template of lulling verses and volcanic choruses are already in the Where Are They Now? file. Black Francis has become Frank Black, releasing a steady string of increasingly irrelevant solo albums. The Breeders career went up the nose and in the arm of the Deal sisters. The Pixies guitarist went MIA into domesticity and the drummer gave up music to become…wait for it…a magician.

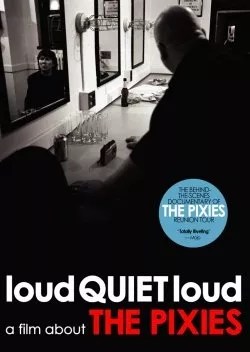

All of which is painstakingly detailed in Fool The World (St.Martin’s Griffin), the just-out he said/she said Pixies bio. Told George Plimpton-style, all in quotes, it reads like a 300-page Spin article and will answer every stupid fanboy question Black Francis stopped answering in 1988. Even more compelling is the 2006 documentary called quietLoudquiet, which sort of turns the reunion tour into reality show. The camera follows them everywhere, including the bathroom. Old dramas like the Kim Deal/Black Francis rivalry seem like ancient history, replaced by more current and pressing concerns, like Deal’s struggle with sobriety and the drummer’s mid-tour meltdown in the wake of his father’s sudden death by cancer.

A coupla years ago, my roommate from college calls me up one day to say the Pixies are getting back together. “Just when I stopped caring,” I said. That wasn’t entirely true. I giddily went to reunion show and contrary to what people who weren’t there the first time around said, they were as good as they ever were. The classic songs seem immune to the ravages of age, and besides the Pixies’ strange allure was never based on the hormones and hair of youth — unlike, say, a band like the Strokes who already seem a bit past it. These days they are all fatter and balder, but, having settled or set aside the irreconcilable differences of the past, and worked through the addiction-rehab-divorce craziness of middle age, they are also wiser.

Something else happened while they were away. This cult band with its weird, noisy songs about UFOs, incest and  bone machines became more famous in death than they ever were in life. They’ve become part of the great collective alt-rock unconscious — like the Cure or the first Violent Femmes record. Surfer Rosa is on every punky bar jukebox. Jocks crank “Wave of Mutilation” as they race by in Daddy’s car, flipping-off the nerds. And every chick bass player worth her salt has played “Gigantic” until her tits practically fell off. When I saw the Pixies reunion, 20,000 people sang along with every word of “Where Is My Mind?” Judging by the median age of the crowd, most were still in short pants when the song first came out. It would seem that the Pixies have become, dare I say it, folk music.

bone machines became more famous in death than they ever were in life. They’ve become part of the great collective alt-rock unconscious — like the Cure or the first Violent Femmes record. Surfer Rosa is on every punky bar jukebox. Jocks crank “Wave of Mutilation” as they race by in Daddy’s car, flipping-off the nerds. And every chick bass player worth her salt has played “Gigantic” until her tits practically fell off. When I saw the Pixies reunion, 20,000 people sang along with every word of “Where Is My Mind?” Judging by the median age of the crowd, most were still in short pants when the song first came out. It would seem that the Pixies have become, dare I say it, folk music.

I suppose we all learned something along the way: Kim can’t be around alcohol; Black Francis needs to lay off the buffets; the guitarist looks a lot cooler with no hair and the drummer needs to finalize his divorce from Vicadin. For me, it’s that Black Francis was right all along. All that soap opera jive? What does it really matter in the end? Especially when the only thing worth remembering is this: If man is five, then the Devil is six and God is seven. Or to put it another way, the Pixies were just four kids from Boston trying to make cool rock music whose monkey died and went to heaven.

In honor of the Pixies kicking off their Doolittle tour at the Tower next Tuesday, I got Black Francis/Frank Black/Charles Kittredge Thompson III on the horn to break down the 21-year-old classic for us track by track.

PHAWKER: We are rolling. So let’s start at the beginning. “Debaser.”

BLACK FRANCIS: “Debaser.” It’s sort of my cliff notes version or the short version of the real thing. My song Debaser would be like The Cliff Notes of the Salvador Dali and Luis Bunuel surrealist film, Un Chien Andalou.

PHAWKER: The film obviously impacted you enough to make a song about it; when did you see it and what did you make of it the first time you saw it?

BLACK FRANCIS: Well, I guess I probably saw it in college in a film class, and I think I just probably thought it was kind of cool, like anything I saw in my artsy-fartsy film class. Anything that reeked of bohemia or you know, Paris in the 1930s or whatever.

PHAWKER: Okay, moving forward, “Tame.”

BLACK FRANCIS: I guess it’s kind of a particular certain kind of girl maybe that I encountered while living in Boston, sort of like the female version of a jock. When I say jock it doesn’t necessarily mean that they’re athletic, more like a frat girl, just sort of what I would call a knucklehead; a female knucklehead. They wear a lot of makeup, high heels, kind of doing all this artificial, sexy stuff that I guess I wasn’t finding very sexy and just finding it kind of crass.

BLACK FRANCIS: I guess it’s kind of a particular certain kind of girl maybe that I encountered while living in Boston, sort of like the female version of a jock. When I say jock it doesn’t necessarily mean that they’re athletic, more like a frat girl, just sort of what I would call a knucklehead; a female knucklehead. They wear a lot of makeup, high heels, kind of doing all this artificial, sexy stuff that I guess I wasn’t finding very sexy and just finding it kind of crass.

PHAWKER: And this woman needed to be tamed?

BLACK FRANCIS: No. Tame, it’s not t-a-m-e-d, but tame as in mediocre.

PHAWKER: Oh, okay, like “that’s tame.” On a related note I wanted to ask you about the screaming; where did that come from? When did you get started with that, and did that take a lot of practicing by yourself to get to that?

BLACK FRANCIS: I’m laughing because you’re asking about screaming and my kids are coming out of this market now, they’re all screaming and a couple of them have really loud screams. [talking to his children] Hey, que paso muchaco! Why don’t you get in the car, alright?… Hi little boy, hi little girl!” [responding to the question] Well, I don’t know. It’s just something I just started to do at clubs back there in Boston. It was just a way to get attention. I don’t know how I arrived at that, but I probably just discovered shortly thereafter that I did it well, and very loud.

PHAWKER: Were you able to do that without totally wrecking your voice for the rest of the night?

BLACK FRANCIS: Yeah. I do it in a way, usually you have a PA and a microphone to help you, but the key, I think is probably you don’t really need to go full tilt. It’s like the opera singers. They look like they’re going full-tilt, but they’re not.

PHAWKER: A trained singer can scream like that without hurting their throat, but I’m wondering if you had any of that kind of training or are you just making it up as you went along…

BLACK FRANCIS: I had some of that training later in more recent years but I suppose whatever I was doing and getting away with it probably physiological, you know what I mean? Genetics.

BLACK FRANCIS: I had some of that training later in more recent years but I suppose whatever I was doing and getting away with it probably physiological, you know what I mean? Genetics.

PHAWKER: Okay, because it sounds pretty lacerating.

BLACK FRANCIS: Some people are genetically able to do certain things with their body that other people can’t.

PHAWKER: Fair enough, let’s move on. “Wave of Mutilation.”

BLACK FRANCIS: I guess I would call it so-called nautical songs, has a lot of references to things from the ocean, you know, playing The Beatles, “Octupuses Garden”, “Yellow Submarine.”

PHAWKER: So the “Wave of Mutilation” would be a tidal wave, a giant wave that came through and killed many.

BLACK FRANCIS: Any kind of wave; it’s the process of the wave. It’s the process of the ocean, the churning of the ocean. It’s the movement of the ocean that turns the mountain into sand or the mighty tree into driftwood.

PHAWKER: On a side note here, explain to me the “Wave of Mutilation (UK Surf Mix),” which I love. How did you decide to do that? Was it a separate session than the Doolittle sessions, or was it just an alternate take?

BLACK FRANCIS: It was recorded in Scotland in the middle of a tour, and you know, the recordcompany they want to promote a record so they release these singles that are supposed to somehow highlight the record and they want extra tracks to boost the sales of that single, so people pay more attention to the songs, they ask you to make extra tracks and sometimes you don’t have them so you slow it down and call it “UK Surf Mix.”

PHAWKER: “I Bleed.”

BLACK FRANCIS: “I Bleed.” Not sure what all that means. Fatalities, but there’s a lot of references to experiences coming from my brief period in Arizona where I worked on the archaeological dig and visited some other famous archaeological sites. That’s part of it. I can’t give you the whole enchilada. Sometimes when you’re writing a song you are very in the moment and it all seems very clear and obvious and then when you are done it’s sort of like a dream and the memory deteriorates very quickly and it’s hard to remember what that was all about.

BLACK FRANCIS: “I Bleed.” Not sure what all that means. Fatalities, but there’s a lot of references to experiences coming from my brief period in Arizona where I worked on the archaeological dig and visited some other famous archaeological sites. That’s part of it. I can’t give you the whole enchilada. Sometimes when you’re writing a song you are very in the moment and it all seems very clear and obvious and then when you are done it’s sort of like a dream and the memory deteriorates very quickly and it’s hard to remember what that was all about.

PHAWKER: Could you tell me a little about these archaeological digs?

BLACK FRANCIS: Yeah it was a famous one, a cave dwelling, I forget the name of hit, but it’s a national historic site. I wasn’t working on that, just visiting. The one I was working on was near Shoefly Village.

PHAWKER: And what were you digging up? What were these the remains of?

BLACK FRANCIS: You know, bones, burial offerings.

PHAWKER: Native Americans or was this just early man?

BLACK FRANCIS: Yeah, Native Americans. We are talking 800 years old.

PHAWKER: Okay. “Here Comes Your Man.”

BLACK FRANCIS: I wrote that when I was about 14 or 15. It’s on an earlier demo. Not sure what it’s about. I think it has to do with the hobo lifestyle. It’s all very abstract, the hobo lifestyle and the Great California Earthquake or something. Something crazy and weird like that.

PHAWKER: Very good. Alright, we’ll move on; “Dead” is the next one.

BLACK FRANCIS: Hmm. That’s a bible story about King David and Bathsheba, Uriah, all that.

PHAWKER: What’s the story with Uriah hitting the crapper? Did they have crappers back then?

PHAWKER: What’s the story with Uriah hitting the crapper? Did they have crappers back then?

BLACK FRANCIS: The one that was sort of murdered by King David was sent off on a suicide mission into battle because he had been sleeping with his wife.

PHAWKER: Have you read the bible from beginning to end?

BLACK FRANCIS: Have I read the bible?

PHAWKER: Yes.

BLACK FRANCIS: Yeah, of course.

PHAWKER: And would you characterize yourself as an agnostic, an atheist, or a believer?

BLACK FRANCIS: Neither, I’m just me.

PHAWKER: (laughs) Okay. “Monkey Gone to Heaven.”

BLACK FRANCIS: I think it’s sort of my ecological song. Told in a sort of abstract story form, sort of about mythical creatures that live in the sky and live in the ocean. It’s the ecological disaster story.

PHAWKER: I always wanted to ask: When you wrote that line about “ten million pounds of sludge from New York and New Jersey,” was that inspired by the drive into New York where you see all this kind of shitty swampland and refineries? That’s what I always pictured when I heard that line.

BLACK FRANCIS: It was actually a reference to a news story at the time about the pile of garbage or whatever off the coast of New Jersey and New York. It was a barge or something, I think that’s an actual reference to something in the news at the time.

PHAWKER: Okay; “Mr. Grieves.”

BLACK FRANCIS: I would say it’s sort of a sister song to “Monkey Gone to Heaven.” Same kind of thing; ecological disaster, with references to mythological figures like Neptune, Neptune’s daughter, really abstract, you know?

BLACK FRANCIS: I would say it’s sort of a sister song to “Monkey Gone to Heaven.” Same kind of thing; ecological disaster, with references to mythological figures like Neptune, Neptune’s daughter, really abstract, you know?

PHAWKER: Does Neptune have a daughter, or did you make that up?

BLACK FRANCIS: (laughs) I don’t remember.

PHAWKER: (laughs) What about the name “Mr. Grieves?” Where does that come from?

BLACK FRANCIS: Grieves is a variation on ‘grief’ and it rhymes with belief — it’s kind of what you’re asking me to do right now is just kind of associative connections between words. That’s what you employ when you write songs in couplets — they have meaning, but the words are chosen because they rhyme. And of course when you’re being ruled by rhyme scheme and things like that when you get to the meaning part of it, it can be open-ended or it can have double meaning or triple meaning or whatever. And why not? You are not writing a science paper where one plus one equals two. There is a science involved where one plus one equals two, but you don’t have to spell that you just have to kind of like, suggest it.

PHAWKER: Okay, I guess you kind of answered the other question I meant to ask about “Monkey Gone to Heaven,” that was the “Man is five, the Devil is six, God is seven,” part — I was wondering if there was a significance to assigning those numbers other than establishing a hierarchy or is it just that seven rhymes with heaven…

BLACK FRANCIS: In the Judeo/Christian tradition beliefs there is a lot of numerical value placed on certain words. Numerology.

PHAWKER: Okay, and it also helps that seven is a two-syllable word. “If God is seven” sounds a whole lot better than “if God is eight.”

BLACK FRANCIS: Well it wouldn’t make any sense if God is eight, you’d be getting away from the whole numerology thing. It’s a balance between rhyme scheme and meaning. If it’s too heavy on either one then it gets out of balance. If it’s too heavy on the meaning then you have no poetry, and if it’s to heavy on poetry then you lose all meaning, and it just becomes pure abstraction. If God is seven, you know, the Devil is six and God is seven, then that is the numerology that it’s referring to; there is no God is eight. I was tapping into Christian numerology that already exists: the five, six, seven thing. Now seven does rhyme with heaven, so that’s a poetry thing.

BLACK FRANCIS: Well it wouldn’t make any sense if God is eight, you’d be getting away from the whole numerology thing. It’s a balance between rhyme scheme and meaning. If it’s too heavy on either one then it gets out of balance. If it’s too heavy on the meaning then you have no poetry, and if it’s to heavy on poetry then you lose all meaning, and it just becomes pure abstraction. If God is seven, you know, the Devil is six and God is seven, then that is the numerology that it’s referring to; there is no God is eight. I was tapping into Christian numerology that already exists: the five, six, seven thing. Now seven does rhyme with heaven, so that’s a poetry thing.

PHAWKER: I got it. Let’s move on: “Crackity Jones.”

BLACK FRANCIS: That’s a biographical song. It’s a song about an old roommate that I had down in San Juan, Puerto Rico when I was when I was going to school there briefly in college.

PHAWKER: I think I read somewhere you called him “crazy, psycho, gay roommate?”

BLACK FRANCIS: I never said that, actually; that was a misquote, and one of the many misquotes that seem to happen with the music press. He did have some mental health issues, but I would have never characterized him as gay. He wasn’t gay.

PHAWKER: Okay, fair enough, and “Crackity Jones?” Where does that name come from?

BLACK FRANCIS: I just made it up.

PHAWKER: It’s a good one. “La La Love You Baby.”

BLACK FRANCIS: I don’t know if the songs means anything, it’s kind of one of those Martin Denny songs or something; it’s just a cartoon kind of sound. You know, partially referencing a wolf whistle [whistles] to kind of like, you know, “I love you, baby don’t mean maybe” is just sort of a dumbing down the pure essence of a popular love song. “All I’m saying pretty baby, la la love you don’t mean maybe.” I mean, that doesn’t sound very serious, does it? It’s mocking, I suppose, but I’m not really making fun or anything; it’s not really inspired by love, it’s inspired by the idea of a love song, I suppose.

BLACK FRANCIS: I don’t know if the songs means anything, it’s kind of one of those Martin Denny songs or something; it’s just a cartoon kind of sound. You know, partially referencing a wolf whistle [whistles] to kind of like, you know, “I love you, baby don’t mean maybe” is just sort of a dumbing down the pure essence of a popular love song. “All I’m saying pretty baby, la la love you don’t mean maybe.” I mean, that doesn’t sound very serious, does it? It’s mocking, I suppose, but I’m not really making fun or anything; it’s not really inspired by love, it’s inspired by the idea of a love song, I suppose.

PHAWKER: Okay, moving on: “No. 13 Baby.”

BLACK FRANCIS: It’s probably about like, you know combination teenage girl crush, low rider girls, gang culture, the number 13. I’s just a combination of teenage feelings combined with where I was growing up where there was a lot of gang activity and all the gang kid at school, so you know I think it was just sort of absorbing the symbolism that was around me.

PHAWKER: Where did you go to school? Are you talking about Grammar School? High School?

BLACK FRANCIS: Junior High and High School.

PHAWKER: And where was this? In California?

BLACK FRANCIS: Los Angeles.

PHAWKER: Okay, moving forward – three more songs and we’re done… I’m sorry, no no no, I lied. Four songs. “There Goes My Gun,” speaking of gang imagery.

BLACK FRANCIS: It’s an abstraction. “Yoo hoo, yoo hoo, yoo hoo,” “there goes my gun”, “Look at me, look at me, look at me, there goes my gun. Friend or foe, friend or foe, friend or foe, friend or foe… there goes my gun.” That’s the lyric right there, so it’s minimalist. What does it mean? I don’t know, it’s associative. What does the sentry cry out? He says “friend or foe?” You give the wrong answer – pow! – right? “Look at me, look at me, look at me, look at me. Yoo hoo, yoo hoo…” I don’t know, does that mean anything? Yeah it means something. Is it so meaningful that you can hang your hat on it? No, but that’s a very typical kind of song for me, as far as writing one, especially at that time.

BLACK FRANCIS: It’s an abstraction. “Yoo hoo, yoo hoo, yoo hoo,” “there goes my gun”, “Look at me, look at me, look at me, there goes my gun. Friend or foe, friend or foe, friend or foe, friend or foe… there goes my gun.” That’s the lyric right there, so it’s minimalist. What does it mean? I don’t know, it’s associative. What does the sentry cry out? He says “friend or foe?” You give the wrong answer – pow! – right? “Look at me, look at me, look at me, look at me. Yoo hoo, yoo hoo…” I don’t know, does that mean anything? Yeah it means something. Is it so meaningful that you can hang your hat on it? No, but that’s a very typical kind of song for me, as far as writing one, especially at that time.

PHAWKER: Okay, next song: “Hey.”

BLACK FRANCIS: Not really sure. It’s just a lot of psycho-sexual psycho-babble, mother/father stuff. I don’t really know; I think you can deduce your own meaning from any particular line, anything you want. Remember these songs are more than 20 years old. This is one of those situations where meaning of what is being written is so far deteriorated I have no idea what I was thinking about when I wrote it. I can no longer say it’s about “this.”

PHAWKER: Well, you don’t have to just tell me what the songs mean; if there’s an interesting anecdote about recording it or playing it live or how you feel about it now compared to then.

BLACK FRANCIS: It’s certainly turned out to be one of the most popular songs at one of our gigs; there’s rarely a gig that we don’t play that song. People love it; it’s The Pixies R&B song. It’s a sort of break-it-down, slower tempo, bring-it-on-down, guitar solo playing the vocal melody… actually it’s not much of a vocal melody. The song breaks down and the guitar player plays a lowly, gentle guitar solo, and everyone goes “woooo!”

PHAWKER: Okay, two more songs: “Silver.”

BLACK FRANCIS: Don’t know what that one’s about. I think it’s a co-write, only one of two that I’ve ever done with Kim [Deal] you know, I think it was probably just some kind of excuse to harmonize. It’s a “ye olde folk song” in 3/4 tempo, you know. I don’t really know if the lyrics have much meaning. I think it was all done kind of very quickly and with very kind of automatic writing. I think that’s one of the few tracks where the band swaps instruments a little bit. When we recorded I seem to recall David playing the bass, Joey playing like the drums or something.

BLACK FRANCIS: Don’t know what that one’s about. I think it’s a co-write, only one of two that I’ve ever done with Kim [Deal] you know, I think it was probably just some kind of excuse to harmonize. It’s a “ye olde folk song” in 3/4 tempo, you know. I don’t really know if the lyrics have much meaning. I think it was all done kind of very quickly and with very kind of automatic writing. I think that’s one of the few tracks where the band swaps instruments a little bit. When we recorded I seem to recall David playing the bass, Joey playing like the drums or something.

PHAWKER: Kim played lap steel I believe.

BLACK FRANCIS: Yeah. That makes sense.

PHAWKER: Okay, last one: “Gouge Away.”

BLACK FRANCIS: Again, one of my Bible stories. This is just, again, a kind of Cliff Notes retelling of the story of Samson and Delilah.

PHAWKER: And they were smoking marijuana?

BLACK FRANCIS: Well, I took some artistic license with that. Maybe they were; there was the Philistines were brought down by Samson. They were in the middle of a three-day celebration, where during that three day celebration people came to the pillars so that they could taunt him and mock him during that party. So, conquering Philistines, if you’re partying for three days, chaining up Superman for all the world to see, I mean I imagine there’s lots of imbibing going on.

PHAWKER: (laughs) You’re saying after three days of partying they might have gotten tired of imbibing wine and moved on to other substances?

BLACK FRANCIS: Well no, it’s just a word to evoke atmosphere.

PHAWKER: Okay, last question here. Is it true that the original working title for the album was Whore?

PHAWKER: Okay, last question here. Is it true that the original working title for the album was Whore?

BLACK FRANCIS: I suppose if you want to call it that, a working title, yeah. It was a memorable enough working title that it was the only working title that anyone could remember. I’m sure there were probably a dozen different working titles.

PHAWKER: And why did you not go with that?

BLACK FRANCIS: I think it seemed too strong of a word. Seemed sort of trying to draw attention to itself or something, you know, it was trying too hard.

PHAWKER: Okay, last question is: 22 years later, where does this album rank in your subconscious? Do you still love this record? Do you like this record? Do you think it’s overrated? Do you think about it differently now than you did then?

BLACK FRANCIS: I’m so far beyond judging it. Whatever judging I’ve done about the record I did 20 years ago, and now it’s just part of my armament. It’s part of my bag of tricks. It’s part of… a good album like that album, it’s like, what I’m known for.

PHAWKER: (laughs) It’s a good bag of tricks, Charles.

BLACK FRANCIS: Well thanks.