BLACKPAST.ORG: In early March 1965 much of the nation’s attention was focused on civil rights marches in and around Selma, Alabama. Activists led by Dr. Martin Luther King used these demonstrations to urge the federal government to act to end the denial of voting rights to tens of thousands of African Americans in Alabama and across the South. When police violence resulted in the death of a demonstrator, Rev. James J. Reeb, a white Unitarian minister from Boston, President Lyndon Johnson in response provided federal protection for the marchers and proposed legislation that would become the Voting Rights Act. MORE

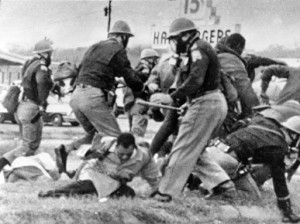

NEW REPUBLIC: Protest at Selma provides a day-by-day account of events in that remote segregated Alabama town during the first three months of  the year as blacks organized, tried first to register at the county courthouse, and then planned a march of protest to the Capital at Montgomery. When their Unarmed column began to cross Pettus Bridge on March 7, Sheriff Clark’s posse, armed and on horseback, attacked with clubs, whips, and ropes. While the blacks huddled together on the bridge in prayer, they were barraged with tear gas, and the state troopers, wearing masks, waded through the group, flailing at heads with their nightsticks. “Unhuman,” one witness termed their behavior. “An American tragedy” was what the president called it. The atrocity at Selma prodded a foot-dragging Congress into passing comprehensive legislation to protect blacks during registration and at the polls. MORE

the year as blacks organized, tried first to register at the county courthouse, and then planned a march of protest to the Capital at Montgomery. When their Unarmed column began to cross Pettus Bridge on March 7, Sheriff Clark’s posse, armed and on horseback, attacked with clubs, whips, and ropes. While the blacks huddled together on the bridge in prayer, they were barraged with tear gas, and the state troopers, wearing masks, waded through the group, flailing at heads with their nightsticks. “Unhuman,” one witness termed their behavior. “An American tragedy” was what the president called it. The atrocity at Selma prodded a foot-dragging Congress into passing comprehensive legislation to protect blacks during registration and at the polls. MORE

LYNDON JOHNSON: I speak tonight for the dignity of man and the destiny of Democracy. I urge every member of both parties, Americans of all religions and of all colors, from every section of this country, to join me in that cause. At times, history and fate meet at a single time in a single place to shape a turning point in man’s unending search for freedom. So it was at Lexington and Concord. So it was a century ago at Appomattox. So it was last week in Selma, Alabama. There, long suffering men and women peacefully protested the denial of their rights as Americans. Many of them were brutally assaulted. One good man–a man of God–was killed.

There is no cause for pride in what has happened in Selma. There is no cause for self-satisfaction in the long denial of equal rights of millions of Americans. But there is cause for hope and for faith in our Democracy in what is happening here tonight. For the cries of pain and the hymns and protests of oppressed people have summoned into convocation all the majesty of this great government–the government of the greatest nation on earth. Our mission is at once the oldest and the most basic of this country–to right wrong, to do justice, to serve man. In our time we have come to live with the moments of great crises. Our lives have been marked with debate about great issues, issues of war and peace, issues of prosperity and depression.

There is no cause for pride in what has happened in Selma. There is no cause for self-satisfaction in the long denial of equal rights of millions of Americans. But there is cause for hope and for faith in our Democracy in what is happening here tonight. For the cries of pain and the hymns and protests of oppressed people have summoned into convocation all the majesty of this great government–the government of the greatest nation on earth. Our mission is at once the oldest and the most basic of this country–to right wrong, to do justice, to serve man. In our time we have come to live with the moments of great crises. Our lives have been marked with debate about great issues, issues of war and peace, issues of prosperity and depression.

But rarely in any time does an issue lay bare the secret heart of America itself. Rarely are we met with a challenge, not to our growth or abundance, or our welfare or our security, but rather to the values and the purposes and the meaning of our beloved nation. The issue of equal rights for American Negroes is such an issue. And should we defeat every enemy, and should we double our wealth and conquer the stars, and still be unequal to this issue, then we will have failed as a people and as a nation. MORE

NEW YORK TIMES: The court pretends it is not striking down the act but merely sending the law back to Congress for tweaking; it imagines that Congress forced its hand; and it fantasizes that voting discrimination in the South is a thing of the past. None of this is true. In the Shelby decision, we see a somewhat more open version of a pattern that is characteristic of the Roberts court, in which the conservative justices tee up major constitutional issues for dramatic reversal. First the court wrecked campaign finance law in Citizens United. On Tuesday it took away a crown jewel of the civil rights movement. And as we saw in Monday’s Fisher case, affirmative action is next in line, even if the court wants to wait another year or two to pull the trigger. Imagine striking down affirmative action and the Voting Rights Act in the same week!

Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act requires certain states and parts of states (mainly in the South) to get permission from the federal government before changing voting rules. The law puts the burden on jurisdictions with a history of racial discrimination to demonstrate that any voting change — from a voter-ID law to moving a polling place — won’t make the minority voters the law protects worse off. In Section 4, Congress provided a formula for determining the jurisdictions to which Section 5 applies — but the data used to construct the formula is from the 1960s or 1970s. Congress renewed the act, most recently in 2006, without touching the old formula.

Back in the 1980s, [Chief Justice Roberts] was President Ronald Reagan’s point person seeking to block Congress’s strengthening of another key provision of the act. (He failed.) As chief justice, Mr. Roberts has famously written that “the way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race.” Colorblindness is fast becoming his signature issue.

Back in the 1980s, [Chief Justice Roberts] was President Ronald Reagan’s point person seeking to block Congress’s strengthening of another key provision of the act. (He failed.) As chief justice, Mr. Roberts has famously written that “the way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race.” Colorblindness is fast becoming his signature issue.

Today’s decision has real consequences. Chief Justice Roberts writes that ”regardless” of how we look at the record, “no one can fairly say it shows anything approaching the ‘pervasive,’ ‘flagrant,’ ‘widespread,’ and ‘rampant’ discrimination” in the past. If that’s true, it’s because the Voting Rights Act works.

Here’s what’s going to happen now. Texas has already announced that it will put its voter-ID law into effect, a law that was on hold under Section 5 awaiting Supreme Court review. Texas’ law, one of the toughest in the nation, requires voters lacking acceptable ID (like a concealed-weapons permit) to travel up to 250 miles at their own expense to get one.

Texas’ law will be challenged on other grounds, but winning voter-ID cases has proved to be tough business. Now Texas can also re-redistrict, freed of the constraints of Section 5, splitting Latino and black voters into different districts or shoving them all in fewer districts to make it harder for them to have effective representation in the State Legislature and in Congress. The biggest danger of what the court has done is in local jurisdictions, where discrimination is more common and legal resources to fight back are thin. MORE

President Lyndon Johnson hands Martin Luther King the pen he signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965 into law.