NEW YORK TIMES: George Jones, the definitive country singer of the last half-century, whose songs about heartbreak and hard drinking echoed his own life, died on Friday in Nashville. He was 81. Mr. Jones — nicknamed Possum for his close-set eyes and pointed nose and later No-Show Jones for the concerts he missed during drinking and drug binges — was universally respected and just as widely imitated. With a baritone voice that was as elastic as a steel-guitar string, he found vulnerability and doubt behind the cheerful drive of honky-tonk and brought suspense to every syllable, merging bluesy slides with the tight, quivering ornaments of Appalachian singing. In his most memorable songs, all the pleasures of a down-home Saturday night couldn’t free him from private pain. His up-tempo songs had undercurrents of solitude, and the ballads that became his specialty were suffused with stoic desolation. “When you’re onstage or recording, you put yourself in those stories,” he once said. Fans heard in those songs the echoes of a life in which success and excess battled for decades. Mr. Jones bought, sold and traded dozens of houses and hundreds of cars; he earned millions of dollars and lost much of it to drug use, mismanagement and divorce settlements. Through it all, he kept touring and recording, singing mournful songs that continued to ring true. MORE

RELATED: “People pay for what they do, and still more, for what they have allowed themselves to become. And they pay for it simply: by the lives they lead.” –James Baldwin

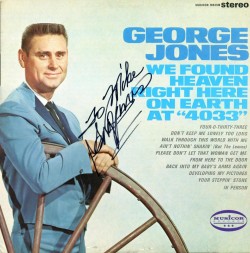

NO DEPRESSION: The George Jones catalogue has now ballooned to such monstrous proportions that it’s no longer possible to say, with any precision, just how many albums have been released with the name George Jones on  them–at this point, an estimate of 300 would probably be conservative. Such an overwhelming inventory has left listeners not a little confused. In The Country Music Foundation’s Country on Compact Disc: The Essential Guide to the Music, Nick Tosches writes of Jones: “no one, great or otherwise, has ever recorded more junk, made more bad records than he.” Tosches is particularly annoyed by the scores of lo-fi Jones repackagings that have been dumped into the marketplace. (My own Possum collection includes cheapy sets on Teller House, Buckboard, Allegiance, Quicksilver, Accord, Picadilly, Pickwick and Pair.) But taking Jones to task for ill-conceived, redundant and muddy remasterings put out by labels for which George no longer worked–Musicor alone released some two dozen Jones LPs after he left in ‘71–makes no sense. You might as well blame Hank Williams for the after-thought strings that got smeared on his recordings when he was dead.

them–at this point, an estimate of 300 would probably be conservative. Such an overwhelming inventory has left listeners not a little confused. In The Country Music Foundation’s Country on Compact Disc: The Essential Guide to the Music, Nick Tosches writes of Jones: “no one, great or otherwise, has ever recorded more junk, made more bad records than he.” Tosches is particularly annoyed by the scores of lo-fi Jones repackagings that have been dumped into the marketplace. (My own Possum collection includes cheapy sets on Teller House, Buckboard, Allegiance, Quicksilver, Accord, Picadilly, Pickwick and Pair.) But taking Jones to task for ill-conceived, redundant and muddy remasterings put out by labels for which George no longer worked–Musicor alone released some two dozen Jones LPs after he left in ‘71–makes no sense. You might as well blame Hank Williams for the after-thought strings that got smeared on his recordings when he was dead.

If we eliminate all the long players tossed out by record companies after Jones had moved on to another label, as well as the innumerable “greatest hits” sets cranked out in his name, that estimate of 300 albums gets reduced (based on the discography available at the Possum Holler website) to an almost manageable 90. I have more than three-fourths of these albums, and they lead me to the precisely opposite conclusion: No one has ever recorded more good records than George Jones.

What Jones hasn’t recorded many of are great albums. Amazing albums marred by one or two abysmal tracks have become something of a Jones specialty. Probably the first truly great Jones album was Sings Bob Wills, a 1962 United Artists record every bit as compelling as Ray Price’s famous Wills tribute and a far sight better than Merle Haggard’s. Jones’ two United Artist albums with Melba Montgomery, 1963’s What’s In Our Hearts and the following year’s Bluegrass Hootenany, make the cut as well. George never made a great album at Musicor, though he never made an actually bad one either. No matter where he’s recorded, though, he has been a singles artist, first and foremost, and it was on the strength of his finest singles that, by the time he left Musicor in 1971, George Jones was already being called country music’s greatest singer. MORE

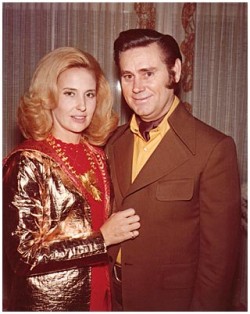

AUSTIN CHRONICLE: His marriage to Tammy Wynette would have seemed a perfect match, bringing together two monumental talents. Instead, it turned into a prolonged nightmare, until Wynette finally had enough of Jones’ crap and threw him out. Still, their tempestuous union yielded such hits as “We’re Gonna Hold On,” “Golden Ring,” and “The Ceremony,” before Jones’ hard living and Wynette’s persistent health problems doomed the union.

AUSTIN CHRONICLE: His marriage to Tammy Wynette would have seemed a perfect match, bringing together two monumental talents. Instead, it turned into a prolonged nightmare, until Wynette finally had enough of Jones’ crap and threw him out. Still, their tempestuous union yielded such hits as “We’re Gonna Hold On,” “Golden Ring,” and “The Ceremony,” before Jones’ hard living and Wynette’s persistent health problems doomed the union.

Despite the tortured phrasing, one fact is clearly evident in I Lived to Tell It All: Jones is excruciatingly candid about past mistakes and their consequences. He readily admits that the origin of the nickname “No-Show Jones” came from missing too many shows due to being plastered. Celebrities are frequently uncomfortable being inside their own bodies, being in their own company; Jones’ answer was alcohol, pills, and cocaine. To fight the depression and shame of drinking, he’d drink more. To find the energy to go on, he’d put a gram of cocaine up his nose.

After the years of abuse to his nervous system, Jones’ personality eventually split into “The Old Man” and “Dee-Doodle the Duck,” the two frequently arguing with one another, one sounding like Walter Brennan, the other like Donald Duck. Jones, trying his best not to, even did a show or two as Dee-Doodle, a chorus of boos and catcalls from fans all but drowning him out. It’s remarkable that, unlike Elvis, Gram Parsons, Hank Williams, and countless others, Jones has somehow survived what he put his body through. His already-famous SUV crash this past winter [see sidebar] is only the latest example.

“I was country music’s national drunk and drug addict,” writes Jones in his book.

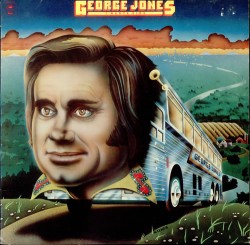

Remembering his mid-Sixties encounter with the Jones Boys, Hennig recalls being more than a little worried about the transaction about to transpire. “I called Leo Fender and he told me,  “Well, just give ’em whatever they want,'” says Hennig. “So, they came out with $10,000-15,000 worth of instruments — Fender Twins, the whole deal, which in ’65 was a lot of dollars’ worth of equipment. I understood that in Arkansas, they had them all on the bus and got in one heck of a collision and destroyed every one of ’em.”

“Well, just give ’em whatever they want,'” says Hennig. “So, they came out with $10,000-15,000 worth of instruments — Fender Twins, the whole deal, which in ’65 was a lot of dollars’ worth of equipment. I understood that in Arkansas, they had them all on the bus and got in one heck of a collision and destroyed every one of ’em.”

Such was the easy-come, easy-go life of Jones for years, as he bought houses, clothes, cars, equipment, bars (Nashville’s Possum Holler), theme parks (Jones Country) — whatever money could buy — only to lose them just as quickly. Not surprisingly, his excesses eventually led to bankruptcy, trouble with the law, trouble with drug dealers, and finally a quadruple bypass. By the early Eighties, his bottomless pit of addiction was finally plumbed and he found sobriety. MORE

RELATED: The Grand Tour by Nick Tosches