BY JONATHAN VALANIA FOR PHILADELPHIA WEEKLY: Near the end of The Royal Tenenbaums, Wes Anderson’s storybook cinematic fable of wasted potential, the character of Richie, a disgraced world-class tennis player with a dark secret, looks soulfully into the bathroom mirror. It’s impossible to say what he’s thinking–he looks scared, confused, angry, on the verge. A tensely strummed acoustic guitar spirals in the background, accompanying a hushed, faintly ominous vocal. It’s Elliott Smith’s “Needle in the Hay.”

Richie picks up a scissors and methodically, if crudely, crops his shoulder-length tresses down to the scalp. He lathers up his lumberjack beard and shaves it clean. He stares hard in the mirror, unblinking, trying to recognize the face he sees.

The music swells, whispery and unnerving. He nods slightly, pops the blade out of the razor and slashes his wrists. In the end, Richie Tenenbaum is saved. Elliott Smith was not. Last week he was found in his apartment in Los Angeles, dead from a self- inflicted knife wound to the chest. Sad to say, deep down nobody who knew him is really all that surprised. He lived in an orbit of despair, and he bore all the usual scars: inconsolable depression, unshakeable addictions, suicidal tendencies.

He was not a pretty man, but his music could win beauty contests. Over the course of five albums, he managed to channel a profound sadness into aching, velveteen folk-rock carols. The best of them sound like mercy itself. Eerily, his entire songbook sounds like a cry for help: harrowing, deeply wounded lyricism wrapped in gorgeous lullaby melodies. That phrase–“a cry for help”–seems so obvious and cliched I’m embarrassed to type it. But that doesn’t diminish its tragic license for truth. What makes a man plunge a knife into his chest? What makes a man jump off a bridge? Or stick a needle in his arm?

The short answer is as obvious as it is cliched: to relieve unbearable pain. That much is undeniable, and yet it explains almost nothing. As old as life itself, suicide remains the cruelest existential riddle. A surrender to the void, a fuck-you to the world. A desperate peace wrested from ordinary horror.

I don’t pretend to know Elliott Smith, but I spent a week with him on tour and at his home back in 2000 when I was profiling him for Magnet magazine. From the outside he looked like the same badly drawn boy you saw peeking shyly out of the scores of high-profile magazine portraits that ran around the time he was nominated for an Academy Award for his song “Miss Misery” from Gus Van Sant’s Good Will Hunting. He was wearing that same brown ski cap he always wore–the one that cocooned him from the world’s harsher frequencies.

At the tail end of a months-long tour in support of his last album, Figure 8, he looked tired and thin. His long hair, unwashed for days, framed his ravaged face. I wrote that he looked like “Christ after three days on the cross.” A bit dramatic, perhaps, but no less accurate.

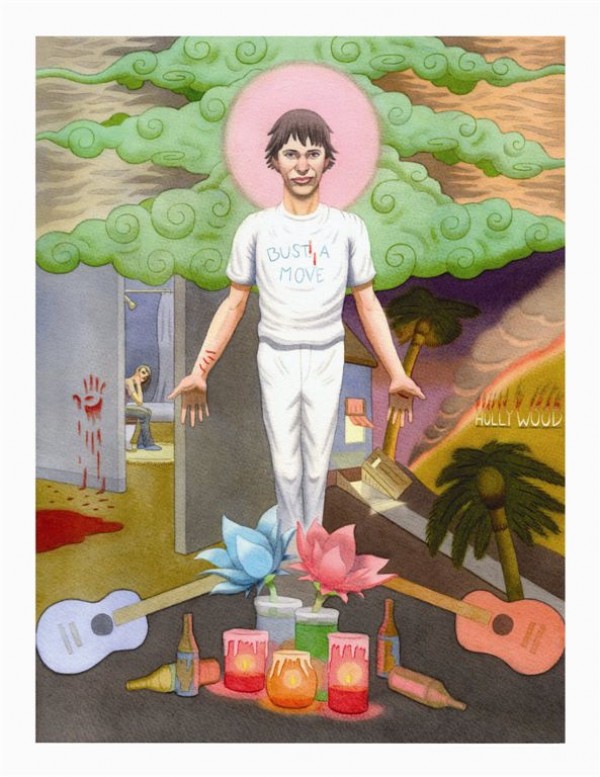

He played me a new song he’d just recorded. In retrospect, the irony of the title is tragic bordering on the grotesque. It was called “A Dying Man in a Living Room.” So much of his art–bits of lyrics, album cover imagery–was a muted blare of distress.

The cover of his second album, simply titled Elliott Smith, featured two people jumping off the roof of a building. Elliot Smith was a very damaged soul. His childhood was rough, a fact underscored by his unwillingness to talk about it.

“There’s not much I could say about that time that I would like to see in print,” he said when I asked him about growing up. “I wouldn’t want to remind any of the people involved of that time.”

By his early 20s, during the flannel glory days of the early ’90s Pacific Northwest, he was playing guitar in a Portland grunge outfit called Heatmiser. After three albums he quit the band, because, he told an interviewer, when you grow up around a lot of yelling and screaming, the last thing you want to do is be in a band where everyone’s yelling and screaming.

He struck out on his own, making music that was the polar opposite of grunge: delicately acoustic, painfully introspective, full of flickering-candle reverie and blurred visions of personal disintegration. With each album, his audience grew–swelling with legions of crushed romantics, the desperately lonely and the clinically sad. Some listened to remember, some listened to forget.

By the time Gus Van Sant showed up, Smith had been crowned indie’s sun king of rainy mood-pop. And yet even as his profile rose, he was collapsing inside. He seesawed up and down between heroin and alcoholism, full-blown depression and tenuous recovery.

“Shoot me up/ It’s my life,” he sang with brutal honesty. Friends staged interventions. There were hospitalizations. At some point, he told me, aided by Paxil, he simply willed himself back into the light with this personal mantra: Things are going to work out and I am never going to stop insisting that things are going to work out. On the last day I spent with Smith, we sat outside his bungalow, tucked away in a leafy section of Silver Lake. I asked him a lot of pretentious big-picture questions about love and death and God. At one point, I asked him if he thought suicide was courageous or cowardly.

“It’s ugly and cruel and I really need my friends to stick around, but dying people should have that right,” he said. “I was hospitalized for a while and I didn’t have that option and it made me feel even crazier.

But I prefer not to appear as some sort of disturbed person. I think a lot of people try to get a lot of mileage out of it, like, ‘I’m a tortured artist’ or something. I’m not a tortured artist, and there’s nothing really wrong with me. I just had a bad time for a while.”

Even then, I could tell he didn’t really believe that. It sounded like whistling past the graveyard.

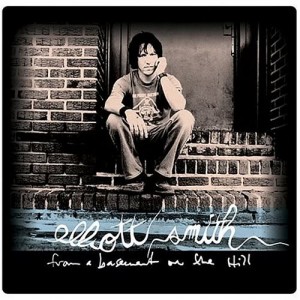

In the two years since I spent time with Smith, I’d heard discouraging things: that he had fallen off the wagon–hard. That his manager–widely seen as one of the pillars of his sobriety–had given up on him and moved on. That his record company passed on his new album, supposedly titled From a Basement on the Hill. His people still loved him, though. He sold out the Trocadero back in June without having released an album in three years. A few weeks ago he released a limited-edition 7-inch on the Seattle-based Suicide Squeeze label which contained two songs: “Pretty (Ugly Before)” and – again, in retrospect, this is about as subtle as writing “redrum” on the mirror in lipstick – “A Distorted Reality Is Now a Necessity to Be Free.” That’s a long way from “things are going to work out and I am never going to stop insisting that they are going to work out.”

Last week things did not work out. I don’t know if he stopped insisting that they would, or he stopped believing what he was saying. Either way, 34 years was all he could stand and he couldn’t take any more. We have to respect that. After all, he made it clear from the very beginning: Sooner or later the world will break your heart. MORE

JONATHAN VALANIA FOR MAGNET: Something terrible happened on the night of Oct. 21, 2003, in the cozy, box-like bungalow at 1857 1/2 Lemoyne Street in the Echo Park section of Los Angeles where Elliott Smith lived with girlfriend Jennifer Chiba. In Chiba’s version of events, the couple had an argument that grew so heated she locked herself in the bathroom. At some point, she heard Smith scream and unlocked the door to see him standing with his back to her. When he turned around, there was a knife sticking out of his chest and he was gasping for breath. Panicked, Chiba pulled the knife out of him, and Smith turned and took a few steps before collapsing. Chiba called 911, and an operator talked her through CPR until the paramedics arrived. Smith was rushed to a nearby hospital, where emergency surgery to repair the two stab wounds to the heart couldn’t save his life.

Back at the house, police found a note written on a Post-It:

I’m so sorry.

Love, Elliott

God forgive me.

When the coroner’s report was finally issued in January 2004, the nature of Smith’s death was maddeningly ambiguous. While the circumstances of the case had most of the hallmarks of a suicide, certain factors also pointed to the possibility of a homicide: the absence of hesitation wounds (the nicks and cuts that come from tentative initial attempts to stab yourself), the fact that Smith didn’t remove his shirt before stabbing himself, a pair of cuts on his hand and arm that could’ve been defensive wounds incurred while fighting off an attacker. There’s also Chiba’s removal of the knife and what police characterize as her refusal to cooperate with investigators, all of which leaves the precise nature of Smith’s death in limbo. Chiba has since refuted police reports that she didn’t cooperate, but the case remains officially open and under investigation.

I don’t pretend to have known Elliott Smith, but I spent about a week with him on the road and at his home when I was profiling him for a MAGNET cover story four years ago. At the tail end of a tour in support of 2000’s Figure 8, he looked tired and thin. His long hair, unwashed for days, framed his ravaged face. I wrote that he looked like Christ after three days on the cross. A bit dramatic, perhaps, but no less accurate. He played me a new song he’d just recorded. The irony of the title is tragic bordering on the grotesque. He told me it was called “A Dying Man In A Living Room,” but it would eventually turn up on 2004’s posthumous From A Basement On The Hill (Anti-) with the title “A Fond Farewell.” […]

From A Basement On The Hill isn’t the last will and testament of Elliott Smith. Alas, that is unknowable, hidden behind a protective wall of silence erected by his family and friends. To try and scale it is a fool’s errand; take it from someone who was fool enough to care and crass enough to try. The true facts of his life are beyond our privilege, beyond our right to know, perhaps correctly so. Maybe that will be one of Smith’s legacies: that the integrity with which he created his art and the decency with which he treated those around him will forever guard the purity of his memory. […] The basement referenced in the title of Smith’s album is located at the bottom of a pricey, split-level house perched on a hill in Malibu that overlooks the glittering blue Pacific. It’s the home of Satellite Park studio, to which a friend directed Smith after his falling out with Brion. The studio is run by David McConnell, a lean and pale 29-year-old songwriter and engineer best known for recording L.A. pop band Goldenboy. McConnell lives at Satellite Park with girlfriend Josie Cotton, who had a new-wave novelty hit in the early ‘80s with “Johnny Are You Queer?”

McConnell hasn’t gone out of his way to court media attention, but if you go out to Malibu and make your way up the steep, winding canyons and knock on the door, he might invite you in for lunch and answer your questions. The house is immaculate, bathed in the white light of Southern California sun and charmingly appointed with tiki-culture totems and a matching leopard-skin rug and couch where Smith would sleep when he was recording here, when he bothered to sleep at all. McConnell remembers Smith and Chiba showing up at Satellite Park in the middle of the night in April 2001, several hours after Smith and McConnell had agreed to meet. Smith took a look around and apparently liked what he saw.

“Can we get started?” Smith asked.

“Right now?” McConnell responded wearily. “Yeah, I guess so.”

That night, Smith and McConnell began a sometimes stormy two-year creative partnership that blossomed into a tight friendship. The recording sessions were alternately stoked and slowed by a cornucopia of cocaine, crack, speed and heroin—always snorted, never injected, according to McConnell—not to mention the dozen or so prescription meds Smith took regularly. The two established a gonzo pace of working on songs until they were completed, often staying up for four or five days in a row. Smith rarely ate anything other than the hundreds of dollars’ worth of ice cream he kept in the freezer.

“I remember one drunken night, we posed for a picture in front of this pyramid he made out of all his prescription bottles,” says McConnell. “Elliott had all these medical manuals, and he loved studying and discussing his meds: Klonopin, Adderall, antidepressants, anti-psychotics. It was crazy. One drug would cancel out the other … Some mornings he would tell me he tried to OD the night before but it didn’t work somehow. He tried to kill himself that way at least 10 times, but it didn’t work. Or at least that’s what he wanted me to believe.” MORE

RELATED: ‘Tis the season, so let’s end with a bit of blasphemy: The loss of Elliott Smith is far more significant than the loss of Kurt Cobain. There. I said it. Both were immensely talented, deeply troubled souls not long for this world. Profoundly bruised on the inside, both earned the right to spend their time on earth doing the backstroke in the deep wells of self-pity. The crucial difference is that Smith’s fall-back position was beauty, no matter how ugly he felt on the inside, and that will lend his songbook a far lengthier shelf life. Cobain’s fall-back position was always ugliness–I hate myself and I want to die, and this is what that sounds like–and maybe one day all his angry noise will mellow into fine whine, like, say, White Light/White Heat-era Velvets. But 10 years A.D., a lot of it just seems to be rusting out in the weeds alongside unsold copies of the last Love Battery album. Quoting Neil Young in his suicide note, Cobain noted that it’s better to burn out than fade away. And while that may be true, Neil also pointed out that rust never sleeps. Elliott Smith never slept much, and he too wrote a suicide note, but he set his to pretty music, and it more or less became From a Basement on the Hill. Despite my misgivings that what I’m about to say might be misinterpreted as glorifying suicide, Basement is my hands-down choice for album of the year. Nothing I heard all year came close to matching its unflinching emotional courage, brutal honesty, druggy swoon and, most important, breathtaking beauty. Smith dubbed the sound he was going for in the last years of his life “California frown,” a post-Prozac update of the orange-sunshine whimsy of Wilsonian West Coast pop–sunbeam harmony, hymnal organ, infinite echo and good vibrations–crossed with Plastic Ono Band junkie confessionals that make William Burroughs’ Naked Lunch look like Breakfast at Tiffany’s. Yes, he was trying to break your heart, but the beautiful difference between life and art is that in art, Elliott Smith doesn’t die in the end. MORE