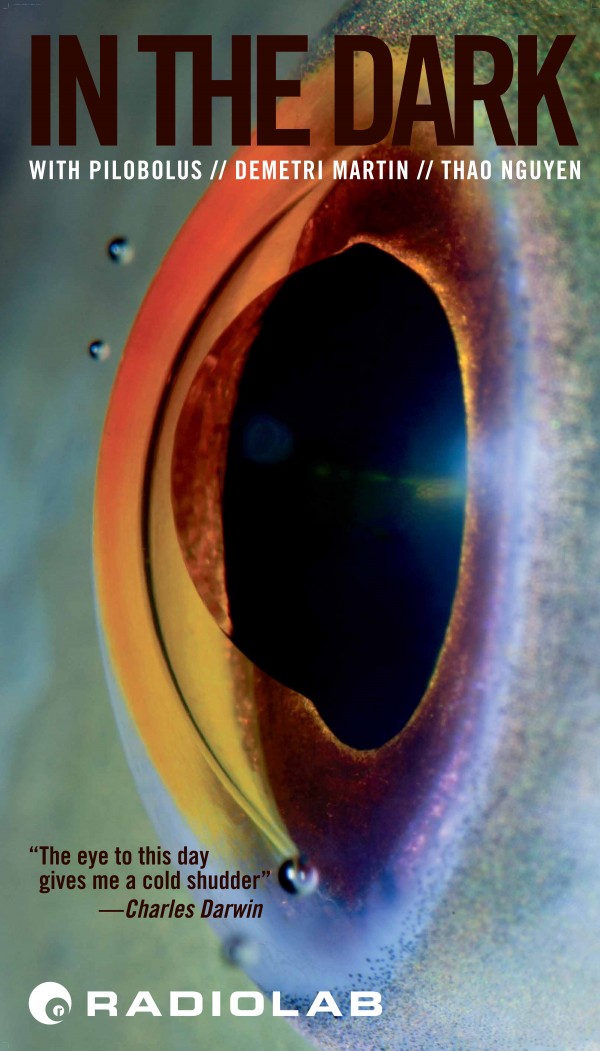

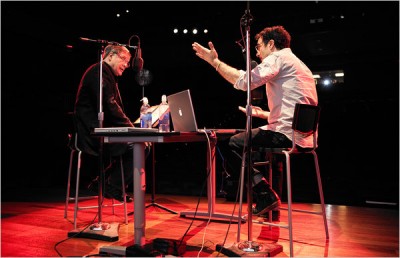

![]() BY JONATHAN VALANIA If you are not already down with the broadcast brilliance that is WNYC’s Radiolab you are doing your life wrong. Every week co-hosts Jad Abumrad [pictured, below left] and Robert Krulwich [pictured, below right] create cinema between your ears. Each episode explores a big-picture topic — time, space, sleep, identity — and comes at it from four or five different angles, co-mingling seemingly disconnected sub-narratives into a lattice of cognition, uncannily mirroring the through lines of consciousness itself. It’s a show about understanding, that, when it works, and it pretty much always does, triggers understanding. Which is a pretty neat trick when you think about it. Radiolab mixes together audio with the precise randomness of Jackson Pollock painting. Up close it may seem chaotic and random, but step back and the method of their madness becomes readily apparent. The resulting episodes — heard by more than a million people each week (and downloaded in podcast form by another 1.8 million) — are cinematic and trippy, deeply intellectual and yet profoundly emotional. There was an episode about sperm where a young woman searches in vain to find the sperm donor fathered her that had me in tears. I suspect I’m not alone. That’s a pretty neat trick, too. Radio that makes you learn something and sometimes makes you cry may not sound like fun, but 2.8 million of us say otherwise. In advance of their appearance at the Academy of Music June 29th — with special guests Demetri Martin, the Pilobolus dance troupe, and musician Thao Nguyen — we got co-host Jad Abumrad on the horn to talk shop.

BY JONATHAN VALANIA If you are not already down with the broadcast brilliance that is WNYC’s Radiolab you are doing your life wrong. Every week co-hosts Jad Abumrad [pictured, below left] and Robert Krulwich [pictured, below right] create cinema between your ears. Each episode explores a big-picture topic — time, space, sleep, identity — and comes at it from four or five different angles, co-mingling seemingly disconnected sub-narratives into a lattice of cognition, uncannily mirroring the through lines of consciousness itself. It’s a show about understanding, that, when it works, and it pretty much always does, triggers understanding. Which is a pretty neat trick when you think about it. Radiolab mixes together audio with the precise randomness of Jackson Pollock painting. Up close it may seem chaotic and random, but step back and the method of their madness becomes readily apparent. The resulting episodes — heard by more than a million people each week (and downloaded in podcast form by another 1.8 million) — are cinematic and trippy, deeply intellectual and yet profoundly emotional. There was an episode about sperm where a young woman searches in vain to find the sperm donor fathered her that had me in tears. I suspect I’m not alone. That’s a pretty neat trick, too. Radio that makes you learn something and sometimes makes you cry may not sound like fun, but 2.8 million of us say otherwise. In advance of their appearance at the Academy of Music June 29th — with special guests Demetri Martin, the Pilobolus dance troupe, and musician Thao Nguyen — we got co-host Jad Abumrad on the horn to talk shop.

PHAWKER: Before we get started I would be remiss if I didn’t point out that your name is like the title of some great lost Captain Beefheart album title…

JAD ABUMRAD: (laughs) That’s good! You know that will make one of our producers here, Tim Howard, very happy. He’s a huge Captain Beefheart fan. I don’t know Captain Beefheart that well, but my name does have a weird, you know, if you say it a certain way it does rhyme. It lends itself to all kinds of different band names and song titles.

PHAWKER: You’re of Lebanese decent. Is that correct?

JAD ABUMRAD: Correct, yes.

PHAWKER: Speaking of music, you went to school and studied composition. That was your plan originally?

JAD ABUMRAD: Yeah. I studied at Oberlin College. I was there for creative writing and music composition. But really writing was something I added later. I went into Oberlin and, pretty much since I was five, I had decided that I was going to be a composer and write music for films specifically. I didn’t quite know what that meant but that was sort of the idea that I had gotten lodged in my head from forever ago.

PHAWKER: You did actually pursue that for a bit before kind of giving up on it. Is that correct?

JAD ABUMRAD: Yeah, I mean I kind of half-assed it away. Ok, so I moved to Tennessee, and this was Tennessee during the [first] Gulf War, so for Lebanese kid it was a little bit of a weird place. I stayed home a lot and I had a four  track cassette recorder and I would basically write strange kind of montage-y, weird surrealistic compositions that were kind of soundtracks for imaginary films. When I went off to school, I pretty much thought I would work toward doing soundtracks for real films. I don’t know, school was sort of an up and down experience but I did come out and work on a bunch of student films, and one feature and a bunch of dance pieces and theatrical things. You know I really enjoyed it. It was great actually but I sort of encountered two problems; one of which was it was really hard to make any money doing that and also you get into a sort of mode that’s almost like a graphic designer where somebody asks you to solve a problem with music, and at that point you’re not really writing music, you’re basically making widgets that fit a certain need. Actually I appreciated it. It’s a really good skill but I found out I just couldn’t do it. I would always write music that was interesting but it just kind of always became the same. It was never really the right style to meet the demands of the people I was working for. So I just wasn’t very good, to put it simply. I somehow couldn’t work in that mode at that time. At the same time I went to school for writing and I was always trying to be a writer, you know, freelancing some essays and journalistic pieces here and there. And that wasn’t really going to well either. At a certain point I quit my day job, which was sort of an internet thing at that point and, I remember having this conversation with my then-girlfriend, now-wife, and she was like, ‘well what do you want to do? What’s the intersection of these two things that you like to do?’ It occurred to both of us that radio is kind of both. I didn’t really listen to the radio but, it seemed like this abstract place where the two meet so I went off to volunteer for a radio station and, I don’t know how many years into the future, I’m now in this weird place that is actually kind of like a scoring film but somehow in disguise. You know, it’s like I’m a journalist first but quietly still a musician, still a film scorer. It’s somehow come back around for me, which has been interesting.

track cassette recorder and I would basically write strange kind of montage-y, weird surrealistic compositions that were kind of soundtracks for imaginary films. When I went off to school, I pretty much thought I would work toward doing soundtracks for real films. I don’t know, school was sort of an up and down experience but I did come out and work on a bunch of student films, and one feature and a bunch of dance pieces and theatrical things. You know I really enjoyed it. It was great actually but I sort of encountered two problems; one of which was it was really hard to make any money doing that and also you get into a sort of mode that’s almost like a graphic designer where somebody asks you to solve a problem with music, and at that point you’re not really writing music, you’re basically making widgets that fit a certain need. Actually I appreciated it. It’s a really good skill but I found out I just couldn’t do it. I would always write music that was interesting but it just kind of always became the same. It was never really the right style to meet the demands of the people I was working for. So I just wasn’t very good, to put it simply. I somehow couldn’t work in that mode at that time. At the same time I went to school for writing and I was always trying to be a writer, you know, freelancing some essays and journalistic pieces here and there. And that wasn’t really going to well either. At a certain point I quit my day job, which was sort of an internet thing at that point and, I remember having this conversation with my then-girlfriend, now-wife, and she was like, ‘well what do you want to do? What’s the intersection of these two things that you like to do?’ It occurred to both of us that radio is kind of both. I didn’t really listen to the radio but, it seemed like this abstract place where the two meet so I went off to volunteer for a radio station and, I don’t know how many years into the future, I’m now in this weird place that is actually kind of like a scoring film but somehow in disguise. You know, it’s like I’m a journalist first but quietly still a musician, still a film scorer. It’s somehow come back around for me, which has been interesting.

PHAWKER: Did you have some sort of special relationship with the radio when you were growing up? Like staying up all night listening to Wolfman Jack on border radio on a little transistor radio tucked under your pillow so your parents don’t hear it, kind of a thing?

JAD ABUMRAD: No. I did not. I think I kind of had this clichéd thing of listening to NPR in the back of the car on the way to school and kind of hating it like a lot of kids, I think. The voices are so modulated and snoozy. But then I do remember actually driving off to Oberlin and we were driving through some dark, open part of Ohio that was just flat and unpopulated and I remember this. Do you remember that radio series Lost & Found Sound?

PHAWKER: Yes.

JAD ABUMRAD: I think one of their stories came on about Tennessee Williams. I could be completely wrong about this but this is how I remember it. This story about Tennessee Williams and this penny arcade. I think Tennessee Williams had been at this penny arcade and made a vinyl pressing? I guess you could do this like a hundred years ago or however long ago, and you could record something direct to vinyl and take it, and somebody found in their basement this old vinyl pressing of Tennessee Williams saying something. The whole piece was kind of built around this lost voice and the way it was edited there were four for five voices talking at once. They were all kind of like intercut in this counterpoint and you heard this beautiful, lost, ghostly audio and there was music and the whole thing kind of felt like music. It kind of moved almost like 16th century counterpoint, the way everything bobbed and weaved and first one voice would lead and then you would hear four or five voices together. I loved it. It was kind of like an on the way to school thing like, I didn’t know you could do that on the radio and in that moment I my idea of what was possible on public radio, or radio at all, was totally transformed. When I was sitting on the bed with my girlfriend, my wife, and having that conversation I thought back to that moment in the car and said maybe I could do stories like that.

PHAWKER: It sounds like a radio show I might have heard on public radio as of late. So out of the blue you just volunteer at WBAI? I’m not familiar with it is so I’m guessing it’s a tiny AM radio station in New York? Is that correct?

JAD ABUMRAD: It’s FM actually. I think 99.5 is the frequency. If you ask people of [Radiolab co-host] Robert [Krulwich]’s generation about WBAI they’ll tell you that was MTV of their generation. It was like a hugely influential very well-listened-to radio station. But when I got there it was way past its heyday and it was a bunch of dysfunctional lefties openly fighting on air. The news department was a shambles. There were these two completely overworked news directors. One of them promptly left and had a sex change the moment I got there. It was like this ragtag motley crew and they were so in need of people to help that I basically walked in and I think I was on the air that day. And I didn’t know shit! I knew nothing! I barely knew how to use the equipment. I had no concept of what it meant to be a journalist or a reporter or anything, but I just happened to walk in at a time when mic access was easy. They were like, ‘You! Please help us! Go cover this protest!’ So I would go out and do these obscenely long, unlistenable twelve minute pieces about whatever the protest of the moment was. I did that for about a year and started to freelance for NPR here and there, and I did a bunch of shows here at WNYC’s On The Media and ultimately Studio 360, I did something for them and I just kind of began to sort of be around a lot. I was working enough where I was just kind of in the building and one day in 2002, I can’t really remember the exact date, I happened to be with the program director at the time who basically had this idea to make a thing called Radio lab and to put it on really late Sunday night. I had no idea how a host was supposed to sound at that point and I had this experience again of just being thrown in way over your head, and for a couple of years filling three hours a week by myself. I was begging people for their old documentaries and various things and in the gaps between the documentaries maybe I’d do a short little piece with some sound design but it was really just me ad hoc for a long time.

JAD ABUMRAD: It’s FM actually. I think 99.5 is the frequency. If you ask people of [Radiolab co-host] Robert [Krulwich]’s generation about WBAI they’ll tell you that was MTV of their generation. It was like a hugely influential very well-listened-to radio station. But when I got there it was way past its heyday and it was a bunch of dysfunctional lefties openly fighting on air. The news department was a shambles. There were these two completely overworked news directors. One of them promptly left and had a sex change the moment I got there. It was like this ragtag motley crew and they were so in need of people to help that I basically walked in and I think I was on the air that day. And I didn’t know shit! I knew nothing! I barely knew how to use the equipment. I had no concept of what it meant to be a journalist or a reporter or anything, but I just happened to walk in at a time when mic access was easy. They were like, ‘You! Please help us! Go cover this protest!’ So I would go out and do these obscenely long, unlistenable twelve minute pieces about whatever the protest of the moment was. I did that for about a year and started to freelance for NPR here and there, and I did a bunch of shows here at WNYC’s On The Media and ultimately Studio 360, I did something for them and I just kind of began to sort of be around a lot. I was working enough where I was just kind of in the building and one day in 2002, I can’t really remember the exact date, I happened to be with the program director at the time who basically had this idea to make a thing called Radio lab and to put it on really late Sunday night. I had no idea how a host was supposed to sound at that point and I had this experience again of just being thrown in way over your head, and for a couple of years filling three hours a week by myself. I was begging people for their old documentaries and various things and in the gaps between the documentaries maybe I’d do a short little piece with some sound design but it was really just me ad hoc for a long time.

PHAWKER: So, somewhere along the way you become interested in sound design and how to apply that to radio. Can we talk a little bit about that? I know you’ve expressed your admiration for Walter Murch and other people that work with film. Can you talk a little bit about that?

JAD ABUMRAD: I remember reading Walter Murch and he had this way of thinking about the relationship between story and sound, between picture and sound, that for the first time gave me a sense of how to explain what I was doing and how to think about it in one kind of rigorous way. He has beautiful schematics about that weird mystery space between words and music and the different kinds of sounds that can operate in a movie. It had never occurred to me that sound exists on this spectrum and that sound design is in some sense not separate to the story. So in a sense, he just provided a way of thinking about it that was holistic. I picked up four of his books and just read them in like one sitting trying to learn how to apply this thing. People would hear it and they would either really like what I was doing or they would find it just aggravating.

PHAWKER: I was going to ask you that. Initially, did a lot of radio veterans tell you that you can’t do that on the radio, you are going to freak people out?

JAD ABUMRAD: Oh yes, I got tons of that. I mean, yes and no. I mean no because no one was listening. I mean nobody was listening to that early stuff. But the people that did really just, I don’t know. It was really hard for me to know initially what made something good and what made something gratuitous. You know, that’s essentially one of the key questions that I figured out over the last how many years, and Walter Murch was part of that. He was like, ‘this is how sound works in a story and this is how visual it is, and this is when you apply it and this is when you don’t.’

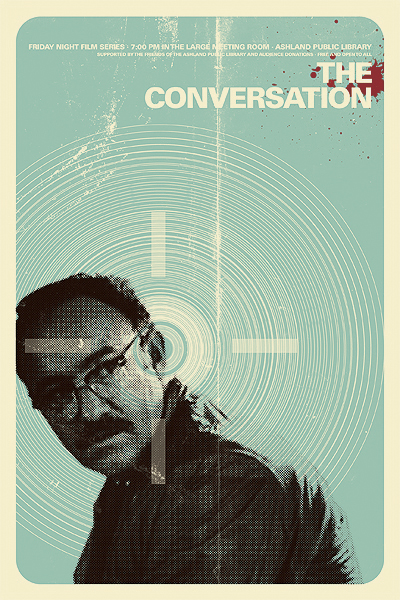

PHAWKER: And Walter Murch, for the benefit of our readers who might not be aware, is the guy who’s done sound design on a number of legendary films starting with The Conversation?

JAD ABUMRAD: The Conversation, the Godfather films…

PHAWKER: Apocalypse Now, which has incredible sound — even all these years later it still sounds pretty mind blowing. Especially that scene where they’re by the bridge that’s blown up and they’re in the trenches and Lance is on acid and there’s all this screaming and gunfire and Hendrix playing on a little cassette player. I don’t know when was the last time you saw [Francis Ford Coppola’s] The Conversation. I saw it again recently and it’s still a mind blowing film audio wise. It still holds up.

JAD ABUMRAD: It’s amazing. He tells a really amazing story about how one of the real discoveries in The Conversation was, you know, how the plot pivots on that last bit of audio. I forget what the phrase is. Do you remember what the phrase is?

PHAWKER: I think it was: “He’d kill us if he had the chance”

JAD ABUMRAD: Right. You hear it early in the film and you don’t know what I means and later in the film they realize that if you change the emphasis of that one word a completely different meaning comes out, and that was the identity of the killer, or something. I don’t quite remember the exact plot, but that was a discovery he made in mid-editing and it’s all about sound. In fact, the movie was all about sound. But it’s just a beautiful movie. It has a sense of dread that creeps over that movie the entire time.

PHAWKER: You guys did an early piece for This American Life that they thought was so awful they refused to broadcast it. Is that true?

JAD ABUMRAD: Yes. I had had this little piece of tape from an old picture book, is that the right word? One of those books that have sound and you’d hear a little beep every time you were supposed to turn the page from the 1950s  and it was about how to properly salute the flag on Flag Day. It was just kind of one of these hilarious kitschy pieces of tape so we kind of, well, he started improvising around it and it ended up being this crazy, weird, nonsensical four minute piece where Robert [Krulwich] played like fourteen different characters and dramatized every little page of this flip book. It’s just weird. It has no reason for being. I don’t know why we made it but we just thought it was hilarious. We sent it to This American Life and they were just like, flummoxed by it. Apparently they had many meetings about how much they hated it. So it was an early failure. Robert thought it was hilarious, he’s like, ‘they just don’t know what they’re talking about.’ But I was so new at that point and This American Life was the pinnacle of what you could do on the radio so I was mortified.

and it was about how to properly salute the flag on Flag Day. It was just kind of one of these hilarious kitschy pieces of tape so we kind of, well, he started improvising around it and it ended up being this crazy, weird, nonsensical four minute piece where Robert [Krulwich] played like fourteen different characters and dramatized every little page of this flip book. It’s just weird. It has no reason for being. I don’t know why we made it but we just thought it was hilarious. We sent it to This American Life and they were just like, flummoxed by it. Apparently they had many meetings about how much they hated it. So it was an early failure. Robert thought it was hilarious, he’s like, ‘they just don’t know what they’re talking about.’ But I was so new at that point and This American Life was the pinnacle of what you could do on the radio so I was mortified.

PHAWKER: I wanted to ask you about a pretty extraordinary episode called ‘Lost and Found.’ If you could summarize this quickly for the readers, I know it’s kind of complicated, and I just wanted to ask you where you came across the story and how it wound up on the air. So let’s just start at the beginning. Explain the premise of it.

JAD ABUMRAD: The show grew out of a basic question of, like, when a body moves through space, like when you go to your friend’s house and you ask him where the bathroom is, and you walk to the bathroom and then you leave the bathroom and then you somehow are able to find yourself back in the living room, in a place you’ve never been before. If you think about what your brain is doing right there it’s basically creating a geographic mental map and then locating it from different points of view and guiding you through it in various ways. It’s kind of an amazing magic trick. So the initial question that got us onto that show was like, how does that work in terms of knowing where you are. Actually physically where you are at any moment. How does the brain do that? What kinds of stories can we tell that can explore that question. About midway through making that show, we had some really interesting stories, it all clustered around that sort of specific mundane question of just orientation — geographic orientation. But one of the silent little keys in that show was about being lost, you know, which is not a fun feeling. It’s about the darkness of not knowing where you are which is a very emotional kind of orientation rather than just a physical one.

So we asked ourselves, what kind of stories can we tell that get at that different way of talking about being unrooted and lost. And mysteriously, right at that moment, a friend of Robert’s had a neighbor who was going through some pretty crazy shit and it was like, hey, you need to check this out, this couple that I know next door to me. This girl just got into a really serious accident. She got hit by a truck while she was on her bike and she’s in a coma and, I think she was about to come out or she had just emerged from the coma at that point and he sort let us in on it. You know, it’s just one of those weird moments of serendipity that happens once every 10 years in this job. We went to interview the guy, the boyfriend, who was in the middle of this traumatic experience with his girlfriend who he had just met nine months ago and fallen deeply, madly in love with in this fairy tale, love-at-first-sight kind of way, but still it was only nine months old. Suddenly, she’s hit by a truck. Basically it looks like she’s going to die or be a vegetable, and he’s sitting there talking to us and we were just somehow stunned by his quiet fierceness. So Robert and I were like, wow, this kid is like 20 years old and I’ve never seen somebody so together in the face of such a terrible, terrible thing. I guess she had just woken up [from a coma] at this point. And then he proceeds to tell us ‘hey, by the way, that moment she woke up, I recorded it on my cell phone.’ So he hands us this cell phone that basically has this series of audio files of him doing the kind of Helen Keller thing where he spells words on her hand and she responds, and for the first time he knows she’s in there. I get chills even thinking about it now. It’s just some of the most spooky, beautiful pieces of tape you’ve ever heard. And that’s the kind of thing that’s never going to happen again for us.

PHAWKER: That’s amazing.

JAD ABUMRAD: Yeah. It was just a fluke. We had been looking high and low. We had gone through maybe twenty different stories and killed them and we just couldn’t find the right match and then that one wandered in in the most fluky sort of way and with characters that are heartbreakingly strong. We stayed in touch with that family because they’re amazing. They’re just such fine people.

PHAWKER: They’re still together, correct?

JAD ABUMRAD: Oh yeah. We just talked to Alan about two weeks ago. Emilie had been in rehab and then she graduated from that, and had gone through a program where she learned to walk again and ride horses even. She’s still blind, and can’t really hear but she just graduated and both she and Alan gave the commencement speech. He’s very protective of her. He doesn’t want the story to overshadow the things she will do. We’ve got a lot of requests from movie people to make this into a movie but he’s always like, ‘no, nope. I don’t want her to have to live in the shadow of the story.’ He’s an extraordinary guy and her recovery is pretty amazing.

JAD ABUMRAD: Oh yeah. We just talked to Alan about two weeks ago. Emilie had been in rehab and then she graduated from that, and had gone through a program where she learned to walk again and ride horses even. She’s still blind, and can’t really hear but she just graduated and both she and Alan gave the commencement speech. He’s very protective of her. He doesn’t want the story to overshadow the things she will do. We’ve got a lot of requests from movie people to make this into a movie but he’s always like, ‘no, nope. I don’t want her to have to live in the shadow of the story.’ He’s an extraordinary guy and her recovery is pretty amazing.

PHAWKER: Well, that’s about as happy an ending from that situation as you could ask for. She’s still compromised physically in some ways, yes?

JAD ABUMRAD: The last I saw her, which was six months ago she had some pretty heavy braces on her legs but she was walking and they were dancing. She can’t really hear or see. She can hear a tiny bit but she’s pretty much completely blind. But I think mentally she’s all there.

PHAWKER: Wow. I’m really looking forward to the live show! Keep up the good work and thank you very much for taking the time to do this.

JAD ABUMRAD: Thanks Jon. This was a very fun conversation. Come and see us after the show.