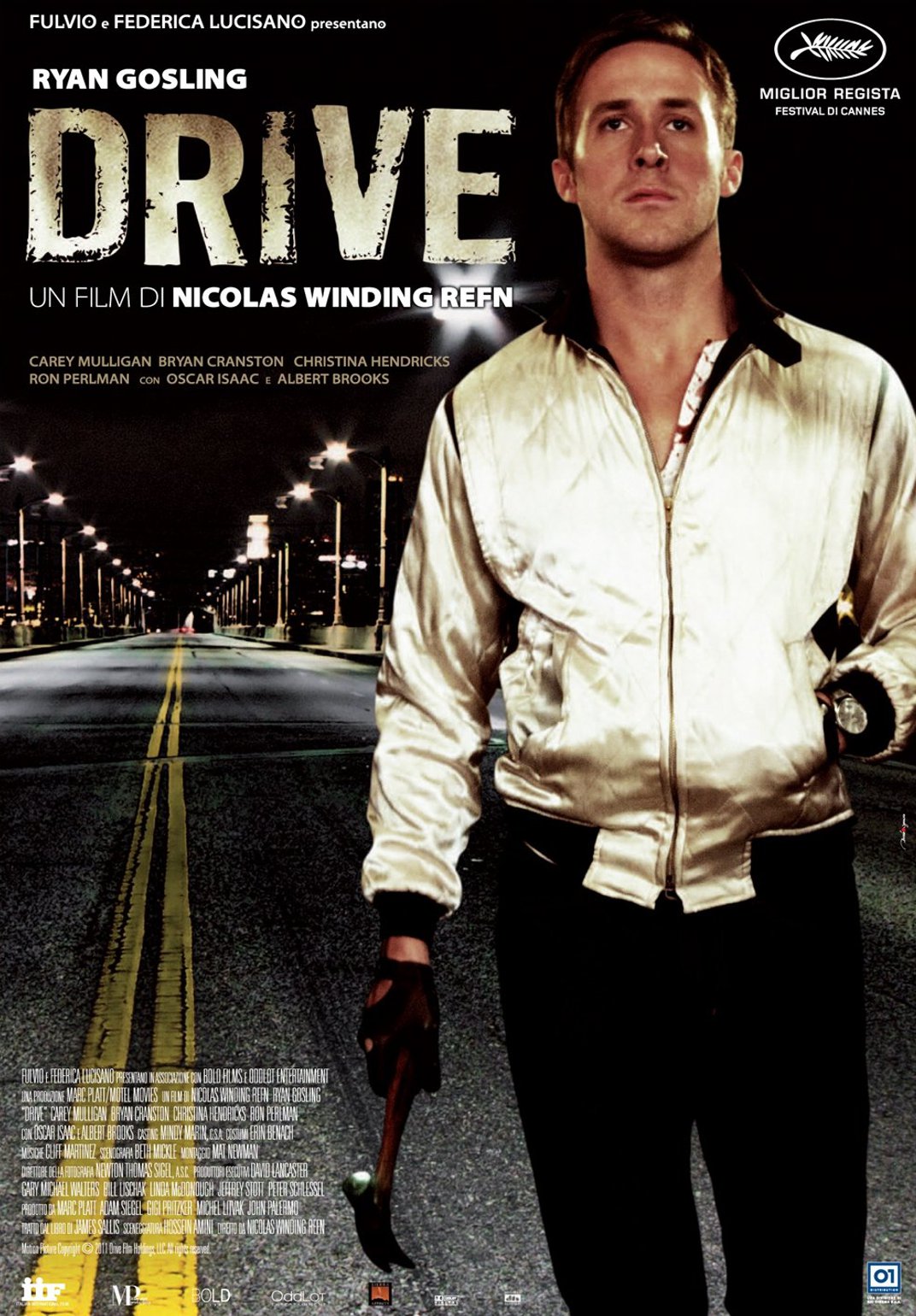

DRIVE (2011, directed by Nicolas Winding Refn, 100 minutes, U.S.)

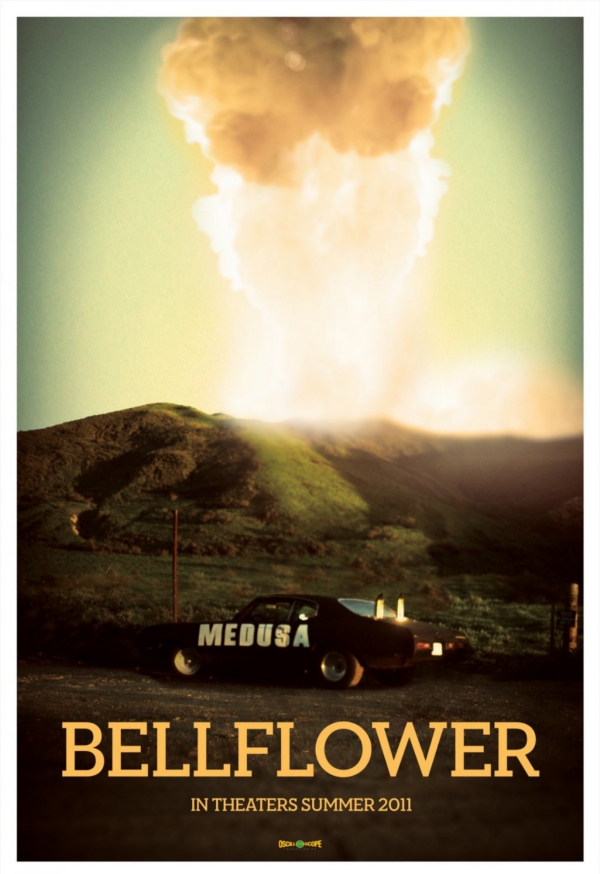

BELLFLOWER (2011, directed by Evan Glodell, 106 minutes, U.S.)

BY DAN BUSKIRK FILM CRITIC After the breathtaking car chase that kicks off director Nicolas Winding Refn’s Drive, the soundtrack plays some very 80s retro synth pop as the opening credits glide by in hot pink. The shade of pink brings to mind cotton candy as the summer fades, and like the fluorescent, feathery confection, Drive hits the sweet spot with a sugary rush, a dazzling mask disguising the fact that its nutritional value is near zero.

But what kind of buzz-killer complains about the negative nutritional value of cotton candy? (Only you, Dan. — The Ed.) Without a doubt Drive is a breathtaking spin through the noir-ish underground of modern L.A. with Ryan Gosling starring as the nameless “Driver.” He lives a life of monk-like austerity, working as a mechanic and stunt driver by day and selling his skills as a getaway wheel man by night. There’s a sort of Zen balance to The Driver’s life, until he falls for single mom Irene (An Education‘s Carey Mulligan), the woman who lives just down the hall in his worn old apartment building. When Irene’s husband Standard (the excellent Oscar Isaac) is released from prison, The Driver is drawn into a poorly-planned heist in order to protect Irene and her kid.

It’s such a generic crime film set up you could imagine anyone from Robert Mitchum to Jason Stratham in the lead, but the film’s familiarity is part of its design. Danish director Refn has taken this story and stripped it like a hot car in a chop shop, showing how much hallucinatory verve he can get out of a mere chassis of a story. By giving The Driver just the bare minimum of characterization, his malleable persona lulls you into merging with him and the film becomes a kind of virtual reality illusion as you are steered through each twist and turn by Refn’s mesmerizing images (it’s not for nothing the film won the director’s prize at Cannes).

Still, all fancy direction wouldn’t gloss over the film’s thin screenplay if it wasn’t for the string of memorable performances Refn gets from his cast. The wild card is comedian Albert Brooks, who gives his most dramatic performance yet as Bernie, a weary mobster who is called upon to bankroll a racing team with The Driver behind the wheel. We expect that Brooks will deliver some out-of-character violence before the film’s end, but his quiet way of calming his dying victim adds an intriguing layer of empathy to this jaded, seen-it-all killer. Carey Mulligan easily exudes Iris’ innocent girlishness and Mad Men’s Christina Hendricks has an effective turn as a dead-eyed accomplice in a heist gone wrong.

But it is Gosling’s performance at the center that helps elevate the film, He has only about 20 lines over the course of the film, his silence bringing to mind the steely reserve Steve McQueen displayed in Bullitt. In fact, a number of film memories are summoned by the film, including Alain Delon’s disciplined hitman in Le Samurai, the lean action films of director Walter Hill (particularly his 1978 film, The Driver) and the foreboding L.A. dreamscape of David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive. Yet for a film that is so deeply pleasurable to watch, something hard-to-define nagged at me after the credits rolled. Something about the way the film so effortlessly conjured the juvenile, sexless fantasies of being an ultra-cool man of few words, racing on the streets and rescuing distressed damsels, that left the film feeling overly calculated and ultimately shallow. Perhaps the film’s 80s veneer reminded me of that old critics complaint from the 80s that MTV has created a aesthetic that champions images over content. Drive recalls classic cinema with its spare narrative but its beautiful sterility also feels kind of empty at its core.

– – – – – – – – –

Maybe Drive‘s one-dimensional male fantasy came off as disappointingly shallow because later the same day I  caught up with Evan Glodell’s highly lauded Sundance hit, Bellflower. Glodell wrote, directed, and stars in this ingeniously crafted drama; heck, he even invented the camera captured its gorgeous sunburned images. At its heart, Bellflower tells the tale of two friends. Woodrow (Glodell) and Aiden (Tyler Dawson) are a couple of tool-wielding twenty-something guys who have moved to a desert town on the outskirts of L.A., where they plan to build a “Apocalypse Car” based on the hot rods seen in the classic action fantasy Mad Max. The pair are peas in pod, joyfully blowing up stuff in the desert with their hand-crafted gadgets when Woodrow meets a woman who comes between the two. Her name is Milly (Jessie Dawson in a tough and believable performance) and Woodrow falls hard after losing to her in a bar’s cricket-eating contest. The sexy and mercurial Milly tells Woodrow right off the bat that she’s going to hurt him, but on their first date the impulsive couple take an unplanned road trip to Texas. Woodrow’s car has a whiskey dispenser jerry-rigged in its dash and the couple drains its reservoir three times as they head down the highway towards the unknown.

caught up with Evan Glodell’s highly lauded Sundance hit, Bellflower. Glodell wrote, directed, and stars in this ingeniously crafted drama; heck, he even invented the camera captured its gorgeous sunburned images. At its heart, Bellflower tells the tale of two friends. Woodrow (Glodell) and Aiden (Tyler Dawson) are a couple of tool-wielding twenty-something guys who have moved to a desert town on the outskirts of L.A., where they plan to build a “Apocalypse Car” based on the hot rods seen in the classic action fantasy Mad Max. The pair are peas in pod, joyfully blowing up stuff in the desert with their hand-crafted gadgets when Woodrow meets a woman who comes between the two. Her name is Milly (Jessie Dawson in a tough and believable performance) and Woodrow falls hard after losing to her in a bar’s cricket-eating contest. The sexy and mercurial Milly tells Woodrow right off the bat that she’s going to hurt him, but on their first date the impulsive couple take an unplanned road trip to Texas. Woodrow’s car has a whiskey dispenser jerry-rigged in its dash and the couple drains its reservoir three times as they head down the highway towards the unknown.

The film enjoys the jovial camaraderie between its overgrown and reckless characters so much it is somewhat surprising when it digs into the aimless ennui beneath their muscle car fantasia. And when Woodrow suffers a head injury, the entire film seems smacked silly as the world spins out from beneath its characters. Glodell is fairly brilliant in visually depicting Woodrow’s mental state and the film’s street-level direction reveals some thoughtful insight into the anger and desperation that goes unmentioned between these closer-than-close pals. Woodrow may dream about blowing up and dragging the world down with him, just as Mad Max does in the climax of his film, but even detonation seems like too much a commitment. Instead, like Dennis Wilson and James Taylor at the end of Monte Hellman’s Two-Lane Blacktop, these similarly lost souls don’t seem capable of doing anything but drifting into oblivion. Like Drive, Bellflower‘s beautiful stylishness could be it own reward, but it dares to ride further and shake its viewers by the shoulders asking, “what are you escaping from anyway?”