WATER FOR ELEPHANTS (2011, directed by Francis Lawrence, 122 minutes, U.S.)

WATER FOR ELEPHANTS (2011, directed by Francis Lawrence, 122 minutes, U.S.)

BY DAN BUSKIRK FILM CRITIC

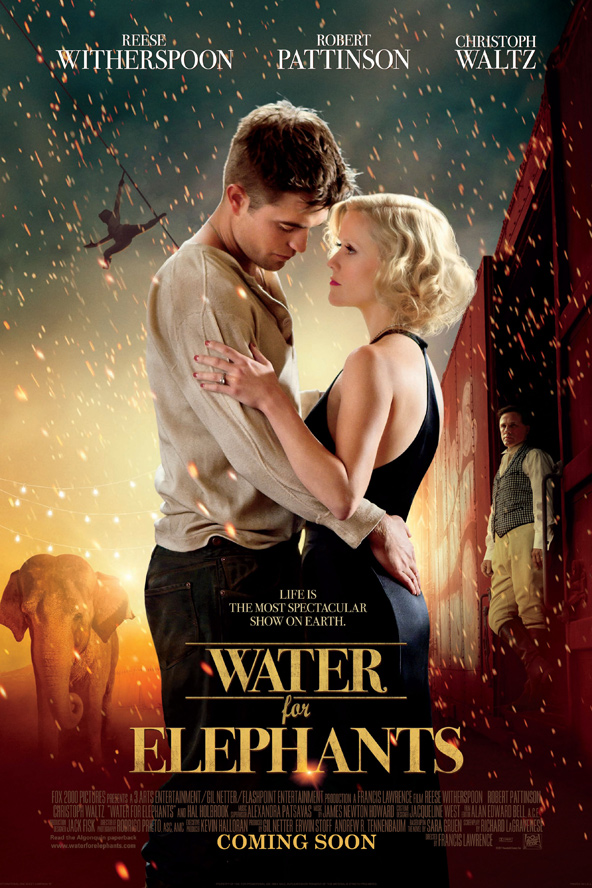

If you thought a seen-it-all big city film critic was too cynical to enjoy a film adaptation of Sara Gruen ‘s Depression-era circus romance Water For Elephants, you would be mistaken. A romantic triangle between a circus owner, his star attraction wife, and an Ivy-League-drop-out turned roustabout is just the sort of old-fashioned hokum that Hollywood once did best. There was every reason to believe that movie stars Reese Witherspoon and Edward the Vampire from Twilight could bring their sizable star power to make Water For Elephants into the type of big-budget throwback that would remind us of Hollywood’s Golden Years. Sadly, it was a foolish optimism, Water For Elephants doesn’t live up to its juicy promise, falling flat in ways that are particularly contemporary: it’s a big top show lacking in authentic spectacle.

Robert Pattinson plays Jacob, a well-off young man who must drop out of his veterinary studies when his parents die in a car wreck. It turns out they hid their debt from Jacob, and without a cent to his name, he is forced to ride the rails looking for work during the depths of the Great Depression. He hooks up with the struggling Benzini Brothers Circus, run by the Machiavellian August (Christoph Waltz, who won the Oscar for his show-stealing portrayal of SS Colonel Landa in Inglourious Basterds), whose trick-riding wife Marlena (Reese Witherspoon) is the show’s star attraction. When Marlena’s lead horse dies, she trades in her horse act for a temperamental elephant. It is Jacob’s job to help Marlena prepare the elephant for the main event and what woman wouldn’t fall for a man who can put a pachyderm through its paces?

Reese Witherspoon is a sight to behold with her dazzling platinum blonde hair and her skimpy circus costumes and Robert Pattinson gives a livelier performance than he has in anything previous but there is a reason that critics have singled out Francis Lawrence’s direction as being particularly inert. If you pay close attention you’ll notice that there is rarely a shot in the film in which two characters engage in a conversation together. Instead, Lawrence keeps his actors isolated from each other in one-shots, cutting away at the end of every line reading to show the other character’s reactions. That way, conversations are completely controlled by the editing, never allowing the actors a chance to establish a rapport, and giving the sensation that the stars might have spent the afternoon in their trailers while their co-stars delivered their lines in solitude to the camera. Which certainly doesn’t add anything to the tepid romantic chemistry between Witherspoon and Pattinson. It’s a sadly common directing style in contemporary American films, and even if audiences don’t recognize it, it is a distance that is felt in the final product.

And if this bit of trickery isn’t enough, there is the distancing effect of watching a circus in which most of the animals and their stunts are helped along with the “magic” of computer-assisted effects. It’s computers that often paste Ms. Witherspoon on the back of that elephant and at the climactic finale, the escaped circus animals look like cartoons as they run amok among the panicking crowd. And when August takes Jacob to ride atop the circus’ boxcars, the actors are not truly showing their sure-footedness, in fact the whole train was created in some programmer’s cubicle. This fakery seems especially egregious because a circus’ stock in trade is honest-to-goodness spectacle, yet here the high-wire is always a mere inch from the ground.

Ultimately it is the novel’s basic narrative drive that keeps Water For Elephants from being unwatchable, along with Christoph Waltz’s performance as the damaged ringmaster/owner August. Waltz’s performance, with his Austrian accent and cool sadism, doesn’t show us much more than we saw in Inglourious Basterds, yet he easily shows a depth that absent in the other characters, making August’s tragedy reverberate deeper than the hero’s triumph. Awash in a sea of false moments, Waltz’s talent quenches our thirst for something, anything, that is truly “real.”