Talk is cheap on the Internet, but at Phawker it’s totally free, baby — at least for you, dear reader. Trolling through the vast and dusty Phawker archives, we have dug up fat sack of conversations worth re-visiting: the always prickish-but-worth-it Will Oldham on authenticity, Americana and his testicles; the inimitable Black Francis susses out Doolittle for us; graphic artiste extraordinaire Charles Burns on the darkness within; author Hampton Sides discusses the banality of Martin Luther King assassin James Earle Ray’s evil; Dave Bielanko discusses Marah’s last chance power try; folk/rock legend Richard Thompson discusses Fairport Convention and reuniting with ex-wife/musical foil Linda Thompson; stained glass sorceress Judith Schaechter discusses sex, lead and divine light; porn star Hollywood crossover Sasha Grey discusses sex and ear candy; Lord of the Trash John Waters discusses Manson, LSD and how Elvis convinced him he was gay; Feelies mainman Glenn Mercer on Alduous Huxley, Peter Buck and whatever happened to the Paisley Underground; and photographer E.C. Adams on Robert Frank, Larry Clark and knowing Mark Ibold. Enjoy.

*

BOOKS: Q&A With John Waters, Lord Of The Trash

[Illustration by ALEX FINE]

We talk about LSD, outsider porn, fuzzy sweaters, uptight gay bars, Charlie Manson, Johnny Mathis, censorship, why the Chipmunks are far superior to the Beatles, why he hasn’t made a film in years and, of course, his new book Role Models, which brings him to the Free Library on Tuesday. [As told to JONATHAN VALANIA]

***

PHAWKER: Before we get started, I want to enter this little fanboy anecdote into the record: My first real girlfriend and I went on our first date to see Pink Flamingos at the midnight movies. We were all of 16. We were appalled and possibly somewhat aroused.

JOHN WATERS: Oh, that’s good! Well, the scary part is that you were aroused.

PHAWKER: Not sure it was the movie per se. I mean, we were 16, you’re kind of permanently aroused at that age, as I recall.

JOHN WATERS: [Laughs]

PHAWKER: But wait, it gets better. Three years later, you came to Allentown, my hometown, to shoot scenes for Hairspray at Dorney Park, and she wound up as one of the featured dancers in the movie! That was big doings in Allentown. We didn’t get a lot of John Waters movies coming through town.

JOHN WATERS: Oh, I love that story.

PHAWKER: The first thing I wanted to ask you about is, in the book, you say you started taking LSD in 1964, which is pretty early on the acid-eater timeline, not quite Cary Grant early, but still. Please explain.

JOHN WATERS: People I knew stole it from Shepherd Hospital, where they were using it to treat alcoholism. It was Sandoz acid. I didn’t really know anything about acid and we took it and it was incredibly pure and strong and I guess it changed me. If I had children and they told me they were on acid I would be very nervous about it. I never had a bad experience, but many of the people I tripped with every week have died. I think it all depends on the person. I realized on LSD that I could do what I dreamed of doing. As I say in the book, my mother always tells me not to tell people that. If somebody gave me acid today I would be horrified. But now they have salvia and meow meow and all these new ones which they say are even more intense. I try to keep up with all the new drugs without actually doing them. The last drug I took in my history of drug-taking was cocaine, but I didn’t like that. And I never took Esctacy because the idea of loving everybody was repugnant.

PHAWKER: How very John Watersian. You also mention in the book, and I thought this was hilarious and deeply cynical, you and your posse sent away for a UNICEF kit and went door to door taking collections that you used to buy acid.

JOHN WATERS: I am embarrassed to admit we did do that. But we were underprivileged ourselves, we didn’t even have enough money for LSD. In hindsight, I give to a lot of charities these days, so I think I made up for my bad karma. Actually, I don’t believe in karma because a lot of good people that I know are dying of cancer and most of the assholes I know don’t.

PHAWKER: You say in the book that you ‘came out’ when you were 17.

JOHN WATERS: I never ‘came out,’ I never said that. That phrase is so corny. I never ‘came out,’ I just was. People were way more afraid that I was something worse than gay. No ever brought it up because they were too afraid to find out. I never fit in with any minority world, and I never fit in with the gay world. Even when I lived in Provincetown, half my friends were straight and the other half was gay. I always ran with mixed crowds. We all fled what we came from to find some new sexual confusion. I still like sexual confusion. If I would go to a gay bar, the person I would like wouldn’t hang out in gay bars either. They would be one of the four lunatics in a hipster bar.

JOHN WATERS: I never ‘came out,’ I never said that. That phrase is so corny. I never ‘came out,’ I just was. People were way more afraid that I was something worse than gay. No ever brought it up because they were too afraid to find out. I never fit in with any minority world, and I never fit in with the gay world. Even when I lived in Provincetown, half my friends were straight and the other half was gay. I always ran with mixed crowds. We all fled what we came from to find some new sexual confusion. I still like sexual confusion. If I would go to a gay bar, the person I would like wouldn’t hang out in gay bars either. They would be one of the four lunatics in a hipster bar.

PHAWKER: If this isn’t too personal a question, what was your a-ha moment when you realized you were gay.

JOHN WATERS: When I saw Elvis twitching, I don’t even think I knew what sex was then but I knew that something was wrong, because nobody else in my class was responding with the same enthusiasm. I fell for Elvis’ pelvis.

PHAWKER: You write about your first trip to a gay bar in Washington, DC when you 17…MORE

***

I HEAR A DARKNESS: Q&A With Will Oldham

[Photo by JEFF RUTHERFORD]

[As Told To JONATHAN VALANIA]

PHAWKER: Okay we’re rolling. Can you just identify yourself for the tape?

WILL OLDHAM: You can do that.

PHAWKER: This is an interview with Will Oldham. And you guys have pulled off to the side of the road; can you tell me where you’re calling me  from?

from?

WILL OLDHAM: Washington, Pennsylvania.

PHAWKER: You tour quite constantly, you’ve released hundreds of songs, more than a hundred singles, or compilation appearances, and yet somehow you’re able to maintain this aura of rarity and fleeting-ness, something like “get on this before it disappears.” I’m wondering how you are able to maintain that with such a prolific output.

WILL OLDHAM: Hmm, I’m not sure. That’s an observation, I guess, from the outside, so I wouldn’t know how that happened.

PHAWKER: OK, let me rephrase that. Do you ever feel like you’re ‘flooding the market’ so to speak, that you’re creating too much Will Oldham out there and that each succeeding release is going to conflict with the one before it? Most bands put out an album every three years, you put out a new one every three months.

WILL OLDHAM: Not really, I mean the makeup of each release unique, the people who are involved, the themes that are addressed, and I feel like most of the things that come out aren’t going to appeal to the same people. There are not a lot of completists out there and I wouldn’t recommend that anyway.

PHAWKER: Do you have favorite albums or favorite songs from your back catalog or are you just kind of always in the moment on this stuff, that what you’re most passionate about is what you’re working on in the moment.

WILL OLDHAM: Again, since they all serve different purposes and work for different reasons. I might have an affection for a particular song or recording session or particular or a particular show that occurred and then it will pass and I’d be on to something else.

PHAWKER: How about this: If the Martians came down today and you had to give them one song or one album to explain Will Oldham’s place on Earth what would you pick?

WILL OLDHAM: I’d just give them one of my testicles, probably. MORE

***

Q&A: Meet The Real Mr. Burns

[As Told To JONATHAN VALANIA]

1. Though born and bred in the high rainyland of the Pacific Northwest, Charles Burns has resided in Philadelphia — Northern Liberties, to be exact — for the past 23 years. “Well, the view out my studio window has changed a bit,” he says, when asked how the ‘hood has evolved over the years. “It used to be homeless guys pushing shopping carts, now it’s mothers pushing strollers.”

shopping carts, now it’s mothers pushing strollers.”

2. Mr. Burns is probably the most important graphic novelist of his time. He we would never agree to this, so don’t bring it up if you see him.

3. The monster-fying sex plague afflicting the horndog stoner teens — half-remembered, half-made-up stand-ins for the friends and exploits of his gloriously misspent youth circa mid-70s Seattle — that people the dark core of Black Hole is not really a metaphor for AIDS. But you would be forgiven for thinking so. “I suppose you can’t write a story about a sexually-transmitted disease without somebody asking you that, but really I just put that in to add to the sense of alienation and the desperation of these circumstances. If it’s a metaphor for anything it’s my tormented adolescence.”

4. Mr. Burns thinks women with tails are sexy. And he will make you think so, too. One of the characters in Black Hole is a beautiful and mysterious artist with more than just the usual junk in the trunk. “I think there is something alluring about it,” he says. “From time to time I do get women coming up to me and telling me how they had a tail when they were born.” Fascinating, captain.

5. Mr. Burns is married to Susan Moore, a painter and fine arts professor at Tyler School of Art. She does not have a tail. Together they have two daughters, aged 18 and 21. “Um, yeah, I guess they are grown-ups,” he says when asked for confirmation. “I am still trying to get used to that idea. It just kinda happened.”

6. Mr. Burns has TERRIBLE handwriting — “Even when I try really hard,” he says with mild exasperation — which is odd for one so adept at drawing clean and exacting lines with pen and ink. But as such, it falls to his wife to do all the lettering in his comics. “I had been sweating over a page for hours, trying to get the lettering to look good, and my wife looked at it and said ‘that looks REALLY terrible’, and I said something to the effect of ‘if you think you can do better…’ and she’s been doing it ever since.”

7. It takes a LONG time to make Black Hole. Serialized through the 90s in 32-page comic book installments once or twice a year, Black Hole has since been published in complete book form. It took Mr. Burns the better part of a year to finish each 32-page installment. “But that wasn’t working on it all day, every day,” he clarifies. “You see, the comics aren’t really my day job. My day job is being an illustrator.” He is referring to the mesmerizingly weird, yet high-profile illustration work he does for the likes of Time, Coca Cola, The New Yorker, Altoids, The New York Times and The Believer. An admitted insomniac with a fairly tireless work ethic, Mr. Burns often begins his work day at three in the morning.

my day job. My day job is being an illustrator.” He is referring to the mesmerizingly weird, yet high-profile illustration work he does for the likes of Time, Coca Cola, The New Yorker, Altoids, The New York Times and The Believer. An admitted insomniac with a fairly tireless work ethic, Mr. Burns often begins his work day at three in the morning.

8. Mr. Burns is very stingy selective with his seal of approval. He is too nice to mention all the bands he declined to draw album covers for, but Iggy Pop is not one of them. “Virgin didn’t have to ask me twice,” says Mr. Burns, an avowed Stooges fan, when asked how he wound up drawing the cover to Iggy’s Brick By Brick. “So basically they were like ‘Do a cover, show it to Iggy and if he likes it we’re done.’ So they give me the address and I go up to New York. Iggy was very nice and normal and it just so happened that Allen Ginsberg was visiting when I showed up. So we all sat around and looked at the cover. Iggy just laughed. I took that as a yes.”

9. He recently finished work on an animated feature-length film called Peur(s) Du Noir (Fears Of The Dark). Mr. Burns is one of six artists (and one of only two Americans) invited by a French production company to write, direct, and shoot a segment of the highly expressionistic film. Peur Du Nour premiered at Sundance back in 2008.

9. He recently finished work on an animated feature-length film called Peur(s) Du Noir (Fears Of The Dark). Mr. Burns is one of six artists (and one of only two Americans) invited by a French production company to write, direct, and shoot a segment of the highly expressionistic film. Peur Du Nour premiered at Sundance back in 2008.

10. In closing, Mr. Burns has never killed anyone, has never voted Republican, and does not believe in God. He does recycle, is well-liked by animals and small children, and he went to college with Matt Groening . He is curiously cagey about whether or not the character of Charles Montgomery Burns is in fact named after him. “You’d have to ask Matt,” says Mr. Burns. “But I will say this, one time I was at some public event [with Groening] and somebody in the audience asked that very question. Matt said, ‘You have to ask my lawyer.’”

does recycle, is well-liked by animals and small children, and he went to college with Matt Groening . He is curiously cagey about whether or not the character of Charles Montgomery Burns is in fact named after him. “You’d have to ask Matt,” says Mr. Burns. “But I will say this, one time I was at some public event [with Groening] and somebody in the audience asked that very question. Matt said, ‘You have to ask my lawyer.’”

***

RAWK TAWK: Dissecting Doolittle With Black Francis

[Illustration by JAY BEVENOUR]

BY JONATHAN VALANIA A word of warning: This is gonna be one of those pieces where I go on and on about my little monkey shines with famous alt-rock personalities. Millions of people love it when I do that, but others seem to get very, very angry about it, stomp their feet and write mean letters that hurt my feelings. If that sounds like you, stop reading right now. I’m serious. I don’t want to even see you in the second paragraph.

BY JONATHAN VALANIA A word of warning: This is gonna be one of those pieces where I go on and on about my little monkey shines with famous alt-rock personalities. Millions of people love it when I do that, but others seem to get very, very angry about it, stomp their feet and write mean letters that hurt my feelings. If that sounds like you, stop reading right now. I’m serious. I don’t want to even see you in the second paragraph.

Set the Wayback Machine to 1988. I’m a college DJ stranded in the middle of Pennsyltucky. Entranced by the naked boob on the cover of Surfer Rosa, I slap it on the turntable and…they had me by the first 20 seconds of “Where Is My Mind?” and never really let go. Shortly thereafter I got a gig working for a Pennsyltucky daily. They asked me one day if I wanted to interview some guy named Black Francis from the Pixies. Would I? Man, this was a dream come true! I could finally learn the WTF of lyrics like, “He bought me a soda, he bought me a soda/ And he tried to molest me in the parking lot.”

When I got him on the phone, he was no doubt bone-tired from endless touring and weary of answering stupid  fanboy questions. He insisted I call him Charles and pretty much refused to give me a straight answer to any question. “Who cares?” he’d say. “We just try to make cool rock music.” I remember thinking: what a dick.

fanboy questions. He insisted I call him Charles and pretty much refused to give me a straight answer to any question. “Who cares?” he’d say. “We just try to make cool rock music.” I remember thinking: what a dick.

The next Pixie I met was Kim Deal, around 1994. The Breeders had just broken huge, and somebody had given Kim’s sister Kelley a copy of my band the Psyclone Rangers‘ debut album. Kelley listed one of the songs as one of her 10 favorites that year in Rolling Stone’s end-of-the-year wrap-up.

So I get her on the phone and we hit it off, and she invites me and the band to come hang out backstage at the Philly stop of Lollapalooza. I don’t remember much except it was hot and muddy and famous back there. The Psyclone Rangers were about to record our next album down in Memphis. We had a song we wanted that patented Deal-sister vocal on, and Kelley quickly agreed to sing on it. The night before she was supposed to fly down she called to say she was too sick to leave town. She sounded pretty out of it. Boy, were we bummed. Was it something we said or did? A few days later, when she got busted for receiving a FedEx envelope full of heroin, we put two and two together.

Fast-forward a year. The Psyclone Rangers are in L.A. playing a special pre-album-release club show for all the music-biz poohbahs. The kid who ran our label always bragged he was friends with Pixies guitarist Joey Santiago and drummer Dave Lovering. Yeah, right! Prove it, we’d always say. That night he did. Apres-gig we’re sitting backstage, and who walks in but the guitar player and the drummer from the Pixies, all smiles and compliments. The Pixies had long since split by then, and Santiago had formed a then-trendy cocktail act called the Martinis. To be honest, it was kind of a letdown: The guys from the Pixies don’t have anything better to do than hang out with chumps like us?

Fast forward a decade. Following Nirvana’s sincerest form of flattery and inspired theft, an entire generation of commercial alt-rock hits built on the Pixies patented song-writing template of lulling verses and volcanic choruses are already in the Where Are They Now? file. Black Francis has become Frank Black, releasing a steady string of increasingly irrelevant solo albums. The Breeders career went up the nose and in the arm of the Deal sisters. The Pixies guitarist went MIA into domesticity and the drummer gave up music to become…wait for it…a magician.

Fast forward a decade. Following Nirvana’s sincerest form of flattery and inspired theft, an entire generation of commercial alt-rock hits built on the Pixies patented song-writing template of lulling verses and volcanic choruses are already in the Where Are They Now? file. Black Francis has become Frank Black, releasing a steady string of increasingly irrelevant solo albums. The Breeders career went up the nose and in the arm of the Deal sisters. The Pixies guitarist went MIA into domesticity and the drummer gave up music to become…wait for it…a magician.

All of which is painstakingly detailed in Fool The World (St.Martin’s Griffin), the just-out he said/she said Pixies bio. Told George Plimpton-style, all in quotes, it reads like a 300-page Spin article and will answer every stupid fanboy question Black Francis stopped answering in 1988. Even more compelling is the 2006 documentary called quietLoudquiet, which sort of turns the reunion tour into reality show. The camera follows them everywhere, including the bathroom. Old dramas like the Kim Deal/Black Francis rivalry seem like ancient history, replaced by more current and pressing concerns, like Deal’s struggle with sobriety and the drummer’s mid-tour meltdown in the wake of his father’s sudden death by cancer.

A coupla years ago, my roommate from college calls me up one day to say the Pixies are getting back together. “Just when I stopped caring,” I said. That wasn’t entirely true. I giddily went to reunion show and contrary to what people who weren’t there the first time around said, they were as good as they ever were. The classic songs seem immune to the ravages of age, and besides the Pixies’ strange allure was never based on the hormones and hair of youth — unlike, say, a band like the Strokes who already seem a bit past it. These days they are all fatter and balder, but, having settled or set aside the irreconcilable differences of the past, and worked through the addiction-rehab-divorce craziness of middle age, they are also wiser.

Something else happened while they were away. This cult band with its weird, noisy songs about UFOs, incest and  bone machines became more famous in death than they ever were in life. They’ve become part of the great collective alt-rock unconscious — like the Cure or the first Violent Femmes record. Surfer Rosa is on every punky bar jukebox. Jocks crank “Wave of Mutilation” as they race by in Daddy’s car, flipping-off the nerds. And every chick bass player worth her salt has played “Gigantic” until her tits practically fell off. When I saw the Pixies reunion, 20,000 people sang along with every word of “Where Is My Mind?” Judging by the median age of the crowd, most were still in short pants when the song first came out. It would seem that the Pixies have become, dare I say it, folk music.

bone machines became more famous in death than they ever were in life. They’ve become part of the great collective alt-rock unconscious — like the Cure or the first Violent Femmes record. Surfer Rosa is on every punky bar jukebox. Jocks crank “Wave of Mutilation” as they race by in Daddy’s car, flipping-off the nerds. And every chick bass player worth her salt has played “Gigantic” until her tits practically fell off. When I saw the Pixies reunion, 20,000 people sang along with every word of “Where Is My Mind?” Judging by the median age of the crowd, most were still in short pants when the song first came out. It would seem that the Pixies have become, dare I say it, folk music.

I suppose we all learned something along the way: Kim can’t be around alcohol; Black Francis needs to lay off the buffets; the guitarist looks a lot cooler with no hair and the drummer needs to finalize his divorce from Vicadin. For me, it’s that Black Francis was right all along. All that soap opera jive? What does it really matter in the end? Especially when the only thing worth remembering is this: If man is five, then the Devil is six and God is seven. Or to put it another way, the Pixies were just four kids from Boston trying to make cool rock music whose monkey died and went to heaven.

In honor of the Pixies kicking off their Doolittle tour at the Tower next Tuesday, I got Black Francis/Frank Black/Charles Kittredge Thompson III on the horn to break down the 21-year-old classic for us track by track. MORE

***

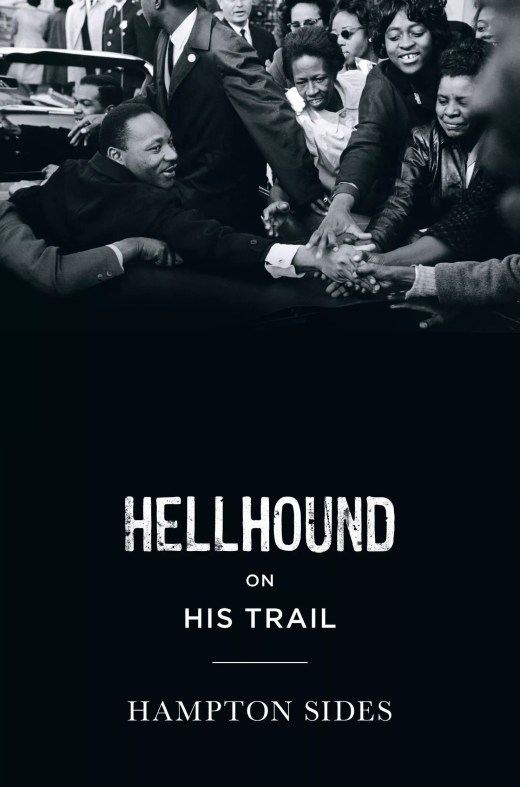

Q&A: With Hampton Sides Author Of Hellhound On His Trail: The Stalking of Martin Luther King, Jr., and the International Hunt for His Assassin

Hampton Sides is an acclaimed bestselling author and a National Magazine Award nominated journalist. He won the PEN USA Award for nonfiction and the 2002 Discover Award from Barnes and Noble for Ghost Soldiers, a historical narrative following the rescue of WWII Bataan Death March survivors that was later adapted into the Miramax feature film The Great Raid. His next book, Blood and Thunder, was adapted into an episode of the Public Broadcasting Service’s American Experience series. Hellhound On His Trail, is a taut and thrilling account of the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., and the 65-day manhunt for his killer, the longest in American history.

PHAWKER: The book is called Hellhound On His Trail, which is a variation on the title of an old Robert Johnson song. Why did you choose that for the title?

HAMPTON SIDES: Memphis plays such a huge role in the book and in the life of Martin Luther King — it was were he came to recruit for his Poor People’s Campaign and it was where he was assassinated. And Memphis is Robert Johnson country, it’s blues country. The song is all about being pursued, either by fate or history or death, depending on how you read the song. It’s all about looking over your shoulder. The book is really about how the FBI is chasing King, and then Ray is chasing King, and then the book changes emotional valence when the FBI is chasing Ray. It’s meant to work on multiple levels.

PHAWKER: In broad strokes, can you explain James Earl Ray’s worldview, specifically as it applies to race.

HAMPTON SIDES: Well, he was a racist. He talked while he was in prison about how killing King would be his retirement plan. He called him Martin Luther Coon. He was contemplating moving to Rhodesia [after killing King], which was a racist/segregationist breakaway state that didn’t have an extradition treaty with the US. He was doing volunteer work for the George Wallace campaign in 1968. None of this necessarily explains why he would pick up a gun and stalk King and try to shoot him. There is some mental illness there, aggravated by long term use of amphetamines. And the idea that he had that he was going to be the ambitious one in his family, I think he did view this as a business proposition, because there were various bounties on King’s head, and I think he hoped that eventually he would collect one of them.

PHAWKER: But he was not a join-the-KKK kind of a racist…

HAMPTON SIDES: No, but he wasn’t a joiner period and he spent a good portion of his adult life behind bars anyway, so it would be hard for him to go to meetings of the local Klan. Also, once he was out he was a fugitive so he was reluctant to get too familiar with any group. And the volunteer work he did for the George Wallace campaign was done under an alias.

PHAWKER: For the benefit of our younger readers, could you explain the George Wallace phenomenon?

HAMPTON SIDES: George Wallace was the former governor of Alabama, who was quite articulate, in his redneck way, at articulating the frustrations of the white underclass. So when he ran for President in 1968 as an independent candidate he enjoyed an initial surge in popularity. It was the most successful independent campaign since Teddy Roosevelt’s Bull Moose party. Wallace was a stone cold racist, he was the guy who stood in the doorway at the University of Alabama to prevent integration. He was governor of the state where Martin Luther King enjoyed most of his Civil Rights victories —  Birmingham Alabama, Selma, Alabama — so there was a sense that MLK and Wallace sort of played off each other and I think that this was a duality that was going on in Ray’s mind.

Birmingham Alabama, Selma, Alabama — so there was a sense that MLK and Wallace sort of played off each other and I think that this was a duality that was going on in Ray’s mind.

PHAWKER: How would you compare the mindset of the average George Wallace supporter with the virulent anti-Obama sentiment of the Tea Party?

HAMPTON SIDES: The culture of hate is still alive and well. Only now it’s armed with technology, specifically the Internet, which has become sort of an echo chamber of hate. These people are out there. There is a lot of chatter, oose talk about taking on politicians and police men. People packing heat at political meetings. Talk about taking the country back, violently if necessary. It’s scary. So I think there is a lot of similarity. I guess Mark Twain was right when he said that history does not necessarily repeat itself, but sometimes it rhymes. And it’s rhyming right now in a lot of stark ways. Demagogues like George Wallace don’t always understand the effect that the poison they are putting out into the world effects certain people. Especially lost souls like James Earl Ray who will take the message literally and pick up a gun and change history. MORE

***

RAWK TAWK: Q&A With Marah’s Dave Bielanko

![]() BY JONATHAN VALANIA All you youngin’s are probably too new here to remember all this, but there was a time back around the turn of the century when Marah — a scrappy little roots-y, beer-lovin’ band of street-urchins from South Philly-by-way-of-Conshohocken — was being groomed to be the second coming of Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band circa The Young, The Innocent & The E-Street Shuffle. Marah was always essentially the brothers Bielanko — Dave, the rakish, boozy street poet with the soulful rasp and the uncanny capacity to channel the heart of the common man and Serge, the oft-bearded six-string straight-shooter with the Cheshire grin who came up with power chords that made his brother’s words ring true — backed by an ever-revolving cast of sidemen.

BY JONATHAN VALANIA All you youngin’s are probably too new here to remember all this, but there was a time back around the turn of the century when Marah — a scrappy little roots-y, beer-lovin’ band of street-urchins from South Philly-by-way-of-Conshohocken — was being groomed to be the second coming of Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band circa The Young, The Innocent & The E-Street Shuffle. Marah was always essentially the brothers Bielanko — Dave, the rakish, boozy street poet with the soulful rasp and the uncanny capacity to channel the heart of the common man and Serge, the oft-bearded six-string straight-shooter with the Cheshire grin who came up with power chords that made his brother’s words ring true — backed by an ever-revolving cast of sidemen.

First came 1998’s Let’s Cut The Crap And Hook Up Later Tonight, a lo-fi home-made compendium of rock-ain’t-dead chants, beer-fueled  breakdowns and alt-country waltzes that put the band in the buzz bin. Then Steve Earle came calling and his now-defunct E-Squared label underwrote 2000’s The Kids In Philly, wherein the band trolled the mean streets of South Philly in search of its inner-Mummer and the huzzahs only grew louder. There were live gig walk-ons with the Boss, and Nick Hornby raved, all of which attracted a small army of discerning rock snobs who demand nothing less than the real deal. Then disaster struck. In a bid for the brass ring, Marah went to England and recorded 2002’s Float Away With The Friday Night Gods with Oasis producer Owen Morris who airbrushed the songs to a slick, radio-friendly sheen. Despite a title track cameo from The Boss, the album failed to connect with a new audience and alienated Marah’s core constituency.

breakdowns and alt-country waltzes that put the band in the buzz bin. Then Steve Earle came calling and his now-defunct E-Squared label underwrote 2000’s The Kids In Philly, wherein the band trolled the mean streets of South Philly in search of its inner-Mummer and the huzzahs only grew louder. There were live gig walk-ons with the Boss, and Nick Hornby raved, all of which attracted a small army of discerning rock snobs who demand nothing less than the real deal. Then disaster struck. In a bid for the brass ring, Marah went to England and recorded 2002’s Float Away With The Friday Night Gods with Oasis producer Owen Morris who airbrushed the songs to a slick, radio-friendly sheen. Despite a title track cameo from The Boss, the album failed to connect with a new audience and alienated Marah’s core constituency.

The band got back to where they once belonged with 2004’s 20,000 Streets Under The Sky and 2005’s If You Didn’t Laugh You’d Cry,  touring extensively and slowly but surely rebuilding their good name. Stephen King took up the cause, telling anyone that would listen that Marah was “the best rock band in America that nobody knows.” Somewhere in there the Bielanko brothers abandoned Philly for Brooklyn. Then in 2008, disaster struck again. On the eve of an extensive tour for the just-about-to-be-released Angels Of Destruction there was a mutiny and the backing band up and quit, effectively scrapping the tour and killing the album. This was the final straw for Serge, who left the band to raise a family. Dave and keyboard player Christine Smith tried to pick up the pieces and moved to a farmhouse out in the middle of Pennsyltucky and set about recording the aptly-titled Life Is A Problem with yet another cast of sidemen. The results are fairly stunning, especially considering the hardships out of which it was created. Life Is A Problem is a lo-fi home-made compendium of we-ain’t-dead chants, beer-fueled breakdowns and alt-country waltzes and as such it completes the circle started with Let’s Cut The Crap And Hook Up Tonight a dozen years ago. Currently on the road to support Life, the reconstituted Marah plays Johnny Brendas tonight. Last week, we got Dave on the horn to discuss this latest Marah meltdown and his Rocky-esque bid to rise once again from the ashes.

touring extensively and slowly but surely rebuilding their good name. Stephen King took up the cause, telling anyone that would listen that Marah was “the best rock band in America that nobody knows.” Somewhere in there the Bielanko brothers abandoned Philly for Brooklyn. Then in 2008, disaster struck again. On the eve of an extensive tour for the just-about-to-be-released Angels Of Destruction there was a mutiny and the backing band up and quit, effectively scrapping the tour and killing the album. This was the final straw for Serge, who left the band to raise a family. Dave and keyboard player Christine Smith tried to pick up the pieces and moved to a farmhouse out in the middle of Pennsyltucky and set about recording the aptly-titled Life Is A Problem with yet another cast of sidemen. The results are fairly stunning, especially considering the hardships out of which it was created. Life Is A Problem is a lo-fi home-made compendium of we-ain’t-dead chants, beer-fueled breakdowns and alt-country waltzes and as such it completes the circle started with Let’s Cut The Crap And Hook Up Tonight a dozen years ago. Currently on the road to support Life, the reconstituted Marah plays Johnny Brendas tonight. Last week, we got Dave on the horn to discuss this latest Marah meltdown and his Rocky-esque bid to rise once again from the ashes.

PHAWKER: Okay we’re rolling; can you please identify yourself?

DAVE BIELANKO: This is David Bielanko from Marah and you are Jonathan Valania. This is an interview with Phawker. I checked it out last night and saw the Richard Thompson thing. That was cool.

PHAWKER: Thanks. So, first off man, I really like the new record. I like the vibe, I like the lo-fi-ness and it’s just a really fucking hot Marah record, I think. But backing up here, where are you right now? 615… are you in Tennessee?

DAVE BIELANKO: No, I borrowed Marty the drummer’s cell phone — he’s from Nashville. We’re at a Red Roof Inn in Jersey across the river from New York.

PHAWKER: Oh, ok. Where are you living these days, out in Amish country last I heard?

DAVE BIELANKO: When things exploded after Angels Of Destruction, I had to move out of that beautiful loft down in South Philly, which was painful, and I needed a place to go, you know, and I wound up out there. One thing led to another and that place sort of personified the music we started making.

DAVE BIELANKO: When things exploded after Angels Of Destruction, I had to move out of that beautiful loft down in South Philly, which was painful, and I needed a place to go, you know, and I wound up out there. One thing led to another and that place sort of personified the music we started making.

PHAWKER: Not to stir up painful memories, but there was a split that happened after the last record, and your brother is no longer actively in the band, is that correct?

DAVE BIELANKO: Yeah, it’s pretty correct. He’s having a baby, or babies to be more accurate. Things just hit the wall. Rock n’ roll bands are houses of cards and the drummer and the bass player tried to stir things up. I was told that I was supposed to fire Christine [Smith, keyboard player] and I wasn’t going to do it. It’s our band, our music and it was our life. I’m not going to have a drummer tell me what to do. You draw a line in the sand and things like pride and egos collided. They decided to pick a fight in the one moment when I couldn’t fight back: there were a thousand dates already booked, the record was about to come out. People tried to get their own way, I don’t know if it was money… whatever, I’ve been through it before, you fall away and go on to great things or whatever.

PHAWKER: So, just to clarify, on the verge of the tour, basically the guitarist the drummer and the bass player split, and kind of left you guys holding the bag?

DAVE BIELANKO: I lost everything that day, including my brother. He just couldn’t fucking deal with it. I lost my manager, my girlfriend, my apartment… everything. Christine put put it back together again. I was just happy to sit around and feel bad for myself slowly but surely she put the pieces back in place and said “hey, it’s therapy of wanna do it.” And I decided I do want to do it. And I’m very, very proud of the record we made. We couldn’t have afforded to do another indie Yep Roc record, just because you don’t see a return on it. MORE

***

RAWK TAWK: Q&A With Richard Thompson

BY ARTHUR SHKOLNIK Quintessential Englishman Richard Thompson has been pushing the boundaries of finger-style guitar since the mid-sixties, when he founded Fairport Convention as a teenager. Five decades and over 40 albums later, Thompson has proven himself a force not to be folked and he is consistently ranked as one of the top five living guitarists and one of the greatest songwriters in recent memory. His newest album, Dream Attic, is a collection of 13 new tracks recorded in real time during a series of West Coast shows. The music continues to emulate life through introspective lyrics and incandescent guitar solos that sherpa the listener through a series of emotional peaks and valleys. The dynamic performances spill over into multiple genres, capturing the high energy of the stage without compromising the accuracy of the studio, which is a testimony to his band’s elevated level of musicianship. Thompson will be playing a solo acoustic set on Sunday at the 49th annual Philadelphia Folk Festival. Recently we got him on the horn to discuss Fairport Convention, his new album, his surprise onstage reunion with Linda Thompson his long estranged ex-wife and former musical partner and his long, proud association with the Philadelphia Folk Fest.

BY ARTHUR SHKOLNIK Quintessential Englishman Richard Thompson has been pushing the boundaries of finger-style guitar since the mid-sixties, when he founded Fairport Convention as a teenager. Five decades and over 40 albums later, Thompson has proven himself a force not to be folked and he is consistently ranked as one of the top five living guitarists and one of the greatest songwriters in recent memory. His newest album, Dream Attic, is a collection of 13 new tracks recorded in real time during a series of West Coast shows. The music continues to emulate life through introspective lyrics and incandescent guitar solos that sherpa the listener through a series of emotional peaks and valleys. The dynamic performances spill over into multiple genres, capturing the high energy of the stage without compromising the accuracy of the studio, which is a testimony to his band’s elevated level of musicianship. Thompson will be playing a solo acoustic set on Sunday at the 49th annual Philadelphia Folk Festival. Recently we got him on the horn to discuss Fairport Convention, his new album, his surprise onstage reunion with Linda Thompson his long estranged ex-wife and former musical partner and his long, proud association with the Philadelphia Folk Fest.

PHAWKER: Okay, please identify yourself…

RICHARD THOMPSON: This is Richard Thompson, speaking to you on behalf of the entire people of Britain.

PHAWKER: (laughs) Very good. You’ve been making music for five decades with 40 or so albums and several hundred songs under your belt. I know it’s a lot of ground to cover, but I was hoping you could try and briefly summarize the narrative arc of your biography.

RICHARD THOMPSON: (laughs) Briefly. I was in Fairport Convention pretty much when I left school at 18. Fairport was a folk punk band and we played the sort of music that was a mixture between traditional music and rock music. I left that band in 1971. Went for about 10 years with my ex-wife Linda, and after that ended I’ve been playing pretty much solid ever since. How’s that? (laughs)

PHAWKER: You were a teenager when you founded and led Fairport Convention?

RICHARD THOMPSON: Correct, yeah.

PHAWKER: Do you miss anything about those days, and are there any parts that maybe you’re glad to have behind you at this point?

RICHARD THOMPSON: (laughs) I miss being young; that was quite exciting. That’s definitely changed. I think there’s a kind of freshness and an originality about the first time that you come to something, you know, the first time you come to music, the first time you come to new ideas.And I think the rest of your life is trying to keep that ability to be naive, to see things for the first time, but when you are young it just happens to you naturally, so I miss that. And I miss the music scene in the 60’s, which I think was very exciting. At the time we thought it was normal, but as decades passed it does seem to have been an exceptional time; a very open-minded time musically, where you had a huge range of styles, and audiences or record buyers seemed to be very open-minded about the kind of music they’d listen to.

PHAWKER: And you mentioned your ex-wife slash musical partner Linda Thompson.

RICHARD THOMPSON: Yep.

PHAWKER: You had recently performed together for the first time in 30 years; can you tell me a little bit about that experience and how it came about in the first place?

RICHARD THOMPSON: Yeah, it came about because we were both performing on a tribute show to Kate McGarrigle, who died this year, and there were many many artists on the bill, and there was a song that Linda was singing on her own, so it started because she needed a guitar accompaniment and I was happy to do that. So, I mean, I could see it as “this is a big reunion,” and it really couldn’t go anywhere else. It was a one night thing and I was sort of the designated guitar player, and it was fine and the audience seemed to like it. MORE

***

REMAIN IN THE LIGHT: A Q&A With Post-Punk Stained Glass Sorceress Judith Schaechter

[”You Are Here” by JUDITH SCHAECHTER]

![]() BY JONATHAN VALANIA Judith Schaechter is a world renowned stained glass artist who has resided here in Philadelphia since graduating from Rhode Island School Of Design in 1983. (It was there that she met acclaimed novelist Rick Moody, then a student at nearby Brown, and the two attempted to be boyfriend/girlfriend, but eventually settled into a friendship that has lasted all these years.) Her work retrieves the lost art of stained glass-making from the dustbin of the Middle Ages — where it largely served as a decorative form pressed into the service of replicating religious iconography — and pushes it through a post-punk filter shot through with sex and death and romance and violence to create something deeply personal, inscrutably modern, and ineffably beautiful. If David Lynch was medieval monk prone to ecstatic visions, presumably after days of fasting and self-flagellation (which were the psychedelic drugs of their day) — well, it would all look a lot like Schaechter’s art. Small wonder her works sell for upwards of $80,000 in the New York gallery scene, and have found a permanent home in The Metropolitan Museum Of Art in New York, the Smithsonian, the Philadelphia Art Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

BY JONATHAN VALANIA Judith Schaechter is a world renowned stained glass artist who has resided here in Philadelphia since graduating from Rhode Island School Of Design in 1983. (It was there that she met acclaimed novelist Rick Moody, then a student at nearby Brown, and the two attempted to be boyfriend/girlfriend, but eventually settled into a friendship that has lasted all these years.) Her work retrieves the lost art of stained glass-making from the dustbin of the Middle Ages — where it largely served as a decorative form pressed into the service of replicating religious iconography — and pushes it through a post-punk filter shot through with sex and death and romance and violence to create something deeply personal, inscrutably modern, and ineffably beautiful. If David Lynch was medieval monk prone to ecstatic visions, presumably after days of fasting and self-flagellation (which were the psychedelic drugs of their day) — well, it would all look a lot like Schaechter’s art. Small wonder her works sell for upwards of $80,000 in the New York gallery scene, and have found a permanent home in The Metropolitan Museum Of Art in New York, the Smithsonian, the Philadelphia Art Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

If the acknowldgement of your peers is a measure of your cred, Schaechter tips the scales. She has received Guggenheim Fellowship, two National  Endowment for the Arts Fellowships in Crafts, The Louis Comfort Tiffany Award, The Joan Mitchell Award, two Pennsylvania Council on the Arts awards, The Pew Fellowship in the Arts and a Leeway Foundation grant. She has taught at The Pilchuck Glass School in Seattle, The Penland School of Crafts, the Toyama Institute of Glass in Japan, The Pennsylvania Academy, the New York Academy of Art, The University of the Arts. and her old alma mater Rhode Island School of Design. Schaechter was included in the 2002 Whitney Biennial and she was a 2008 USA Artists Rockefeller Fellow.

Endowment for the Arts Fellowships in Crafts, The Louis Comfort Tiffany Award, The Joan Mitchell Award, two Pennsylvania Council on the Arts awards, The Pew Fellowship in the Arts and a Leeway Foundation grant. She has taught at The Pilchuck Glass School in Seattle, The Penland School of Crafts, the Toyama Institute of Glass in Japan, The Pennsylvania Academy, the New York Academy of Art, The University of the Arts. and her old alma mater Rhode Island School of Design. Schaechter was included in the 2002 Whitney Biennial and she was a 2008 USA Artists Rockefeller Fellow.

On the heels of a recent exhibition at the Claire Oliver Gallery in Manhattan, Phawker got Schaechter on the horn for a career retrospective. We discuss the ironies of an atheist working in a religious art form, the mind-bending valuations of the current art market, the dangers of working with lead and what it’s like to have singer of the Stone Temple Pilots as your most famous patron. The short answer is that you get to hang out back stage with the Meat Puppets.

PHAWKER: Let’s start at the beginning, how did you decide to do what you do?

JUDITH SCHAECHTER: Ah, well I went to art school — because I was a nerd, and that’s what nerds do. I had taken a lot of painting classes. But I remember that when I was really young my parents used to take me to this art center, and the only materials they had there were for making collage — and I loved it because I really wanted all those materials for my dollhouse. So I put them all together in a collage and took it home and ripped it apart and put it all in my dollhouse. But back to the future, I didn’t get into stained glass until after college, where I was a painting major. At school the painting studio was right next to the glass studio and I used to wonder in there. Almost everyone who walks into a glass studio falls in love with the glass-blowing process because it’s very balletic and theatrical and quite seductive. But for whatever reason I was really turned on by the stained glass glass and I tried very hard to get into but it was already full. My intention was just to make a doo-dad for my window, but almost immediately, weeks at the most, I knew this was what I wanted to do for the rest of my life. In hindsight I have to ask myself: Is there something in me that makes me predisposed to liking this medium so much? And all can think of is that I was very fond of Lite Brite, I mean really fond of Lite Brite. I remember they used to have these patterns that you could follow to create pictures, but I would always make my own. And I also always liked those bake-in-the-oven suncatchers and stuff.

PHAWKER: It’s a very rare form, correct? Not many people are working in this medium these days, correct?

JUDITH SCHAECHTER: That’s a nice way of spinning it. Another way would be to say it’s a dead medium. It came and it went, basically. There are people who do stained glass and I know them all. It’s a very small field, it’s not taught in art school. The industry, if you want to call it that, survives on artisans and family studios that have been passed down from generation to generation. It is certainly not taught as an artistic discipline with any degree of seriousness. MORE

***

Q&A: Who Is Sasha Grey

BY PAUL J. MAHER JR. Sasha Grey brings to mind the character of the wicked Cathy Ames in John Steinbeck’s 1952 novel, East of Eden, a psychological and physical likeness so eerie that it bears detailing.

BY PAUL J. MAHER JR. Sasha Grey brings to mind the character of the wicked Cathy Ames in John Steinbeck’s 1952 novel, East of Eden, a psychological and physical likeness so eerie that it bears detailing.

Steinbeck writes:

“It is my belief that Cathy Ames was born with the tendencies, or lack of them, which drove and forced her all of her life. Some balance wheel was misweighted, some gear out of ratio. She was not like other people, never was from birth. And just as a cripple may learn to utilize his lack so that he becomes more effective in a limited field than the uncrippled, so did Cathy, using her difference, make a painful and bewildering stir in the world.”

Cathy’s physiognomy, apart from hair and eye color, suggests Grey as well: “As though nature concealed a trap, Cathy had from the first a face of innocence. Her hair was gold and lovely; wide-set hazel eyes with upper lids that drooped made her look mysteriously sleepy.” Grey often looks stoned, though she is not, she exudes lucidity and passion about any subject lobbed at her. However, it is the mindset Steinbeck describes, that eerily pins her down, as if the master novelist had also written her off the pages. She is an “inner monster,” not malformed without legs or arms, but malformed within: “To a man born without conscience, a soul-stricken man must seem ridiculous. To a criminal, honest is foolish. You must not forget that a monster is only a variation, and that to a monster the norm is monstrous.”

When Sasha Grey is interviewed, she reveals the same smugness that she relies upon in her acting roles, whether it’s a film by Steven Soderbergh or  Erik Everhard. It was one of the characteristics most Girlfriend Experience critics puzzled over; is she acting, being herself, or a little of both? Chelsea’s cold demeanor allowed no passage of emotion to enter or leave. Instead, she must be what men pay her to be. We can only guess that her private dynamics with fiancé Ian Cinnamon but we could safely surmise that that too probably follows the same pattern she follows with onscreen fiancé Chris. Each must suffer the indignity of knowing that the main woman in each of their lives offers themselves to other men for a fee.

Erik Everhard. It was one of the characteristics most Girlfriend Experience critics puzzled over; is she acting, being herself, or a little of both? Chelsea’s cold demeanor allowed no passage of emotion to enter or leave. Instead, she must be what men pay her to be. We can only guess that her private dynamics with fiancé Ian Cinnamon but we could safely surmise that that too probably follows the same pattern she follows with onscreen fiancé Chris. Each must suffer the indignity of knowing that the main woman in each of their lives offers themselves to other men for a fee.

Grey often employs a wry half-smile, a sort of crooked leer, like a teenaged girl caught in the act of lying, ashamed, with no recourse but to laugh it off. During her sex scenes, she is less of a performer than she appears to be the sacrificial offering of the lamb to the tigers. This is no performance art; it’s actually less performance than art. It’s certainly no Cirque de Soleil. Her sex scenes are robotic, like a duck to water, with the only variation on a theme being the spurious lines of dialogue she spouts as a means of turning on her viewers and even then she resorts to time-worn clichés. Her performance is commonplace, another cog in the greased wheel of a multi-million dollar enterprise chewing up and spitting out the lost, lonely and left-out young females of our nation. There are no victims, she claims, and to that we must agree to disagree. MORE

***

RAWK TAWK: Q&A With Glenn Mercer Of The Feelies

![]() BY JONATHAN VALANIA The Feelies are one of those inscrutable but beloved band’s bands whose influence far exceeds their royalty statements and, as a consequence, the period on the last sentence in their bio keeps turning into a comma. Borne of the suburban garages of North Haledon, New Jersey, they released Crazy Rhythms in 1980 to massive acclaim and minimal sales and then promptly split off into a myriad of minor side projects, only to resurface again in 1986 with the altogether wonderful The Good Earth, produced by Peter Buck, guitarist for REM, whose early sound is deeply indebted to the inviting ambiguities and pretty persuasions of the Feelies’ aesthetic. Two major label releases would follow — 1988’s Only Life and 1991’s Time For A Witness — and that was pretty much all she wrote. Although a funny thing happened on the way to the cut-out bin in that The Feelies pretty much forged the template for much of the indie rock that would follow: A dense web of jangling guitars and zooming raga-like drones, percussion-heavy rhthyms played at double latte tempos, incantatory lead vocals mixed as understatement of the year. Fast forward to 2008, when the reactivated Feelies once again turned the period at the end of their bio into a comma. Last March at Johnny Brendas the band was living proof that not much has really changed all these years later. They still dress like grad studies professors, with dual frontmen/guitarists Bill Million and Glenn Mercer rocking matching pleated khakis. They still love turning a good classic rock cover sideways (”She Said, She Said” and “Paint It Black), crazy-tempoed rave-ups like “Slipping (Into Something)” have lost none of their amphetamine pep, and the Feelies’ brand of indie-rock raga can still make a sold out club audience wiggle wildly like worms on a hook despite the preponderance of graybeards and thinning pates in the crowd. With a set list that drew liberally from their glorious middle period, the Feelies recreated once-upon-a-time college radio staples such as “The High Road” and “Deep Fascination” with impeccable precision, warmth and clarity, not to mention that sense of mystery at the center of their music that always suggested they knew much more than they let on.

BY JONATHAN VALANIA The Feelies are one of those inscrutable but beloved band’s bands whose influence far exceeds their royalty statements and, as a consequence, the period on the last sentence in their bio keeps turning into a comma. Borne of the suburban garages of North Haledon, New Jersey, they released Crazy Rhythms in 1980 to massive acclaim and minimal sales and then promptly split off into a myriad of minor side projects, only to resurface again in 1986 with the altogether wonderful The Good Earth, produced by Peter Buck, guitarist for REM, whose early sound is deeply indebted to the inviting ambiguities and pretty persuasions of the Feelies’ aesthetic. Two major label releases would follow — 1988’s Only Life and 1991’s Time For A Witness — and that was pretty much all she wrote. Although a funny thing happened on the way to the cut-out bin in that The Feelies pretty much forged the template for much of the indie rock that would follow: A dense web of jangling guitars and zooming raga-like drones, percussion-heavy rhthyms played at double latte tempos, incantatory lead vocals mixed as understatement of the year. Fast forward to 2008, when the reactivated Feelies once again turned the period at the end of their bio into a comma. Last March at Johnny Brendas the band was living proof that not much has really changed all these years later. They still dress like grad studies professors, with dual frontmen/guitarists Bill Million and Glenn Mercer rocking matching pleated khakis. They still love turning a good classic rock cover sideways (”She Said, She Said” and “Paint It Black), crazy-tempoed rave-ups like “Slipping (Into Something)” have lost none of their amphetamine pep, and the Feelies’ brand of indie-rock raga can still make a sold out club audience wiggle wildly like worms on a hook despite the preponderance of graybeards and thinning pates in the crowd. With a set list that drew liberally from their glorious middle period, the Feelies recreated once-upon-a-time college radio staples such as “The High Road” and “Deep Fascination” with impeccable precision, warmth and clarity, not to mention that sense of mystery at the center of their music that always suggested they knew much more than they let on.

PHAWKER: Where an I reaching you? Where are you based these days?

GLENN MERCER: North Haledon, New Jersey.

PHAWKER: Going back to the origin of the band name, it’s based on Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, correct?

GLENN MERCER: Yes

PHAWKER: Now, for the benefit of those who haven’t read the book, including myself…

GLENN MERCER: I haven’t read it either. Were you going to ask if it made a reference to the book?

PHAWKER: I was going to ask if you had read the book and what impact it had on you.

GLENN MERCER: I think it’s like movies of the future. Kind of a virtual reality type situation.

PHAWKER: So who came up with the band name?

GLENN MERCER: Bill [Million] did.

PHAWKER: So I guess I’d have to ask him that. So you guys are famous for this very distinctive guitar sound that you came up with over the years, and I’m curious how you guys arrived at that.

GLENN MERCER: Well mostly from the kinds of bands we liked and listened to. I guess when you’re first starting out, you don’t have big aspirations. You definitely shy away from the flashy guitar solo kind of thing. You gravitate more toward people like Pete Townsend and more simple rhythmic folks really. Ron Ashton and The Stooges were a big influence. Guys in the Velvet Underground, Alice Cooper; a lot of those guys had two guitars. The play between the guitars was crucial to the sound.

PHAWKER: When did you first encounter the Velvet Underground?

GLENN MERCER: That would be ‘67 I think.

PHAWKER: What were you doing? Did you see them live?

GLENN MERCER: No, but a friend of mine was at their very first show. They played at a high school in New Jersey. For me though, it was just hearing  the record. I had two older brothers who were avid record collectors and they would go out and buy stuff. They would read about bands in underground newspapers and stuff, so they weren’t that obscure at first.

the record. I had two older brothers who were avid record collectors and they would go out and buy stuff. They would read about bands in underground newspapers and stuff, so they weren’t that obscure at first.

PHAWKER: How old were you in ‘67?

GLENN MERCER: Thirteen.

PHAWKER: What about The Stooges, did you encounter them roughly the same time as well?

GLENN MERCER: Yeah, I think their first record was ‘69.

PHAWKER: But in the 60’s, did you encounter them in real time?

GLENN MERCER: Oh, well I was into rock and roll even before then. The Beatles and British Invasion music. I didn’t own a guitar at that point, but that kind of inspired me to play. Then going back from The Beatles to Buddy Holly and that era was another influence. I listened to a large amount of stuff.

PHAWKER: Why was there such a long gap between the first album and The Good Earth, which is, by the way, one of my all time favorite albums from the 80’s.

GLENN MERCER: Well, we basically broke up and reformed. Got involved in a lot of offshoot bands. We just kind of laid low for a little while.

PHAWKER: You had kind of a disillusioning experience with Stiff, who put out the first record?

GLENN MERCER: Well, it was a lot of different things. I think one big obstacle was that [original drummer] Anton [Fier] preferred to play quite often, really. More than we’d like to. Back then, you couldn’t do kind of a national low budget tour. College radio really wasn’t that strong at that point. It wasn’t until R.E.M. and the 80’s when you could do a low budget tour and go across the country. Back around the time of Crazy Rhythms, the big cities like Boston, Chicago, L.A., we didn’t have much tour support, so we really couldn’t do that. We didn’t really play that often. Anton got frustrated and joined a side band. That was another element, as well as the fact that we were evolving as songwriters and Stiff wasn’t really too happy with the demos we made then. It was really a combination of things. Anton quitting was really the breakup though.

PHAWKER: This new direction that you were heading, was that more akin to the vibe of The Good Earth?

GLENN MERCER: Actually, it was more like what we did on The Willies.

PHAWKER: For the benefit of people who may not know, what are you referring to? How would you categorize that?

GLENN MERCER: It was my band that was a little more low key, more like instrumental passages. The closest I could come to describing it is something less commercial sounding with more drumming and more percussion.

PHAWKER: There seems to be a distinctly different vibe to the band between the first and second record. It feels less angular and herky-jerky, if you will. I’m guessing the new rhythm section had an impact on that?

GLENN MERCER: Yes, that was definitely a factor. It was sort of an evolution, kind of not wanting to stay in one place too long. A lot of it had to do with environment, and the time they were made. The angular sound you mentioned was popular at the time. Bands like R.E.M. and the whole college scene sort of had an effect on The Good Earth. We could do the cross country thing, and we were able to cross paths with bands like the Minutemen, Rain Parade, Green on Red. Just a whole different sort of atmosphere. MORE

***

Q&A: With Philly-Based Photographer E.C. Adams

PHAWKER: Let’s start with some basic bio info: where are you from, where did you go to school, how did you wind up in Philly, and what was the aha moment that made you want to become a photographer?

E.C. ADAMS: I was born in Louisville, Kentucky. My parents died (at different times) when I was a small child; I then moved in with relatives in Lancaster, PA. I attended a small private school in Lancaster. After that, several ”prodigal son” episodes were intermingled with stints at a few different universities, the last being Temple, where I was a French major. But the main reason I moved to Philly was because I’d gotten a job as a black-and-white darkroom printer in 1988.

There was no real “aha” moment. When I was about 20 years old, a roommate of mine had a small darkroom, and he also sold me an old Nikon F; he showed me how to use both of them, probably in a couple of hours. Apart from that, I have no “formal” training in photography.

PHAWKER: How would you describe your visual style? What photographers — or for that matter any other visual artists – had a deep impact on your  aesthetic?

aesthetic?

E.C. ADAMS: Some people have said my work looks a little bit like Robert Frank — but mine is more mood-driven and autobiographical/personal rather than documentary, particularly in the last few years. And some of my pictures are flat-out meaningless art photography, albeit taken in real-life situations – for example, one hobby of mine is finding “as-is” still lifes in situ. I guess the photographer who influenced me the most was Larry Clark, who inspired me because he made a career of taking pictures about his life and of his drug-addled friends, rather than specifically going out on a photographic mission — for the most part, anyway.

PHAWKER: Let’s talk about gear. What do you shoot with? Are you entirely digital now?

E.C. ADAMS: I shoot mostly with Leica and Nikon 35mm film cameras. I feel more connected to their primitive analog functionality, and also feel reassured by the tried-and-true archival durability of B&W film — as in, “Do you know where your JPEGS will be 50 years from now?” I also like film because you often don’t see your results for days or weeks after you’ve shot the photographs, thereby psychologically distancing yourself from the subject matter. On a practical level, I’ve also re-discovered shots I took when I was much younger that I didn’t appreciate at the time; had I been shooting digital back then, those images would have undoubtedly been deleted. That said, I also have several digital cameras, which of course are necessary for any kind of paid work, as well as any other project where instant results or large quantities of material are needed. Plus they’re fun to use sometimes, and the little digicams are convenient.

PHAWKER: Please explain the circumstances behind the Ed Rendell photo that first brought you to our attention. He looks like a man off his meds in that pic.

E.C. ADAMS: I took that picture at the Memorial Day parade in Mayfair a few years ago. Ed was marching in the parade, I think alongside the vintage Corvette brigade. To be perfectly honest, I don’t even remember taking that specific picture, and I have NO idea why his hands are in the air (as if he’s paying tribute to Helios, God of the Sun). As to whether or not he’s off his meds, well, you’ll have to ask his physician.

PHAWKER: We noticed Mark Ibold’s name mentioned in our CV, please elaborate.

E.C. ADAMS: It’s funny that I still have that music stuff on my resume! I was trying to pad it out some years ago, I guess before I’d, well, padded out the photography part. Anyway, I grew up with Ibold (Pavement, Sonic Youth) in Lancaster; I’ve known him since 4th grade. We had a short-lived so-called “band” in Lancaster in 1982 called The Adonis Brothers (if you fish around the “Music and Noise” section of my website you’ll find some MP3’s of music I did myself or was involved in with other people). That was probably the first recording of him playing bass — one note over-and-over again – and/or vocalizing. But in reality, it was merely an excuse for underage drunkenness and noise-making. Tim Finefrock — another Lancaster dude, later of East Village country/metal band Raging Slab — was the drummer. MORE