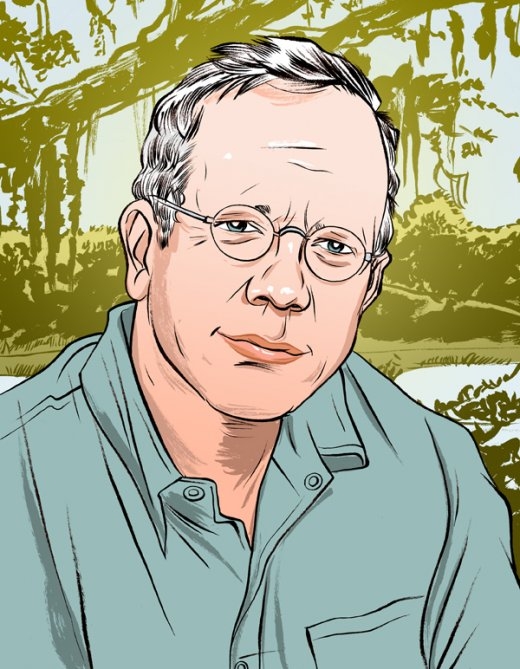

[Illustration by ALEX FINE]

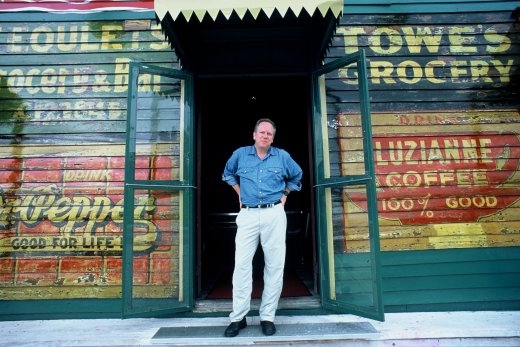

![]() BY JONATHAN VALANIA Nick Spitzer is a folkorist, ethnographer, professor of American Studies at Tulane University and host of the altogether wonderful American Routes — which can be heard locally on WHYY from 2-4 PM on Saturdays and 4-6 PM on Sundays — a heady Creole gumbo of blues, folk, soul, rock and Cajun stylings. Each week Nick scours the highways and the byways, the juke joints and roadhouses, the coffeehouses and corner bars, of these United States to map the crazy quilt patchwork of regional flavors, customs and musics to, in effect, create an audio flowchart that tells us where we were and how we got here. Think of him as a doctor pressing a stethoscope to the nation’s breadbasket to measure the heart beat of the American dream boogie, and every week he asks you to take a listen and give a second opinion. Spitzer currently resides in New Orleans, but he has local connections: he studied anthropology at Penn in the late 60s and DJed at WMMR in the wild and wooly dawn of FM in the early ’70s. We talked about all of this, as well as the evolution of the show, his career arc as an American roots explorer and life in the Big Easy post-Katrina. (His full bio can be viewed HERE)

BY JONATHAN VALANIA Nick Spitzer is a folkorist, ethnographer, professor of American Studies at Tulane University and host of the altogether wonderful American Routes — which can be heard locally on WHYY from 2-4 PM on Saturdays and 4-6 PM on Sundays — a heady Creole gumbo of blues, folk, soul, rock and Cajun stylings. Each week Nick scours the highways and the byways, the juke joints and roadhouses, the coffeehouses and corner bars, of these United States to map the crazy quilt patchwork of regional flavors, customs and musics to, in effect, create an audio flowchart that tells us where we were and how we got here. Think of him as a doctor pressing a stethoscope to the nation’s breadbasket to measure the heart beat of the American dream boogie, and every week he asks you to take a listen and give a second opinion. Spitzer currently resides in New Orleans, but he has local connections: he studied anthropology at Penn in the late 60s and DJed at WMMR in the wild and wooly dawn of FM in the early ’70s. We talked about all of this, as well as the evolution of the show, his career arc as an American roots explorer and life in the Big Easy post-Katrina. (His full bio can be viewed HERE)

PHAWKER: What brought you to Penn back in the late ’60s?

NICK SPITZER: My father wanted me to go to Columbia until he saw it burning down in 1968. Penn wasn’t burning yet — though it did soon after — and my mother wanted me to go to Yale, but I thought that was too close and I was fed up with WASPY Connecticut and dour Yalies. I applied to Penn because I was interested in economics. I came to Philly and I was just very impressed with the campus, the scene, Philadelphia. My parents wanted me to be in the Wharton School, but by the time I arrived I was no longer doing everything they thought I ought to be doing. After I spent half a year at the Wharton school I was looking to transfer into anthropology,  which was a rather big change in terms of what they all thought I’d be doing. It was good because Penn has a really great Anthropology department and had a lot of programs related to American studies and folklore — things that were important to me… to be they don’t really do them now.

which was a rather big change in terms of what they all thought I’d be doing. It was good because Penn has a really great Anthropology department and had a lot of programs related to American studies and folklore — things that were important to me… to be they don’t really do them now.

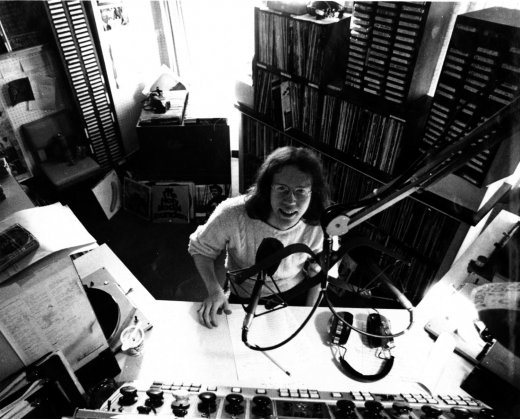

After I had been at Penn for a semester I discovered WXPN, which at the time was a student-run radio station, and I think had a tremendous legacy as that. The record collection at WXPN became as important to me as the world culture archives in the anthropology department. I also became a pretty dedicated local culture person. I mean I didn’t just stay on campus: I went to the Italian market — which wasn’t too cool if you had long hair — and South Street, which as Orlon’s song goes was where “All the hippies meet.” It was still a struggling African-American street scene where you could hear people singing on the sidewalks, go to Harry’s Occult Shop, hear some music in the little jazz clubs. I just got more involved in Philly in general. By the time I graduated I had done fieldwork around Philly — you know they don’t give you a job as an anthropologist with a BA in anthropology — but I had worked at XPN and my girlfriend at the time, Carol Miller, was on MMR and I knew Michael Tearson pretty well because he had been on MMR and a student at Penn. I went down to MMR to give my tape, and after splitting Philly somewhat dejectedly — like oh god, I’ve been living in Philly my whole new-consciousness life, what am I gonna do, the draft board is coming after me — and the MMR station program director called me up and said we want you to come down here and host the morning show as an audition. So I came down and did it and I also was their production director for a while, and that got me involved in Philly several more years after college. (I also managed to not get drafted…but that’s another story) So Penn, XPN and MMR had kind of cemented my relationship to the city. I’ve come back a lot for everything from Penn reunions to academic conferences to radio events. So I stay in touch and I really like Philly—it’s one of my favorite cities.

PHAWKER: As a folklorist or an ethnographer is there something whenever you come back to Philly you sort of do as a sort of ritual, like a restaurant you go to, a neighborhood you visit?

NICK SPITZER: I go down to the steak places. Pat’s is what I always started with back then so I still go back to Pat’s. I really dig just going around South Philly and seeing all the mom and pop restaurants and shops; and I’ve  always loved the window décor in south Philly, all the home altars and the family displays. I like going to the Penn campus. There’s something fascinating about what students are like today and what students were like then… I try not to be a crusty old alumnus, but XPN is not what it was when I was there; it’s much more of a commercial format with few students really involved except as worker bees. Still, I have a lot of friends around Philly from those days. Heath Allen plays piano and composes, a friend from college. Last time I was there I went down to Bob and Barbara’s. They had a really great old-school organ trio [the late Nate Wiley & The Crowd Pleasers], which reminded me of some the little black jazz clubs in the ’70s. Clubs I used to go to, like the Aqua Lounge and Grendel’s Lair and the Bijou. I used to go to a club called Just Jazz downtown; I saw Earl Hines there, and McCoy Tyner played The Aqua Lounge, and all the old Coltrane band people. I look for these things. I’ve got a lot of friends who take me places. I have to say when I was just in Philly the last time, I was at this event at Penn that the urban studies people put together and sat with Mayor Nutter at dinner. I found out he used to be a disco DJ when he was in college, so we had a good time talking abut discoing and DJ-ing. I always find something; Philly is a city of deep and wide vernacular culture, and I think it is a city that a lot of Americans still forget exists. They think of it historically as far as the Continental Congress and Ben Franklin and all colonial era landscape, but they forget this is a major East Coast city filled with fascinating neighborhoods… and the Third World is there, but so is sort of the Old World and old Philly. It’s much more intimate to me than New York and much more warm and friendly than Washington. I really like Philly. I also like Baltimore, but I know Philly better, so when I come back I’m always exploring and learning what’s happening now and it’s a pleasure.

always loved the window décor in south Philly, all the home altars and the family displays. I like going to the Penn campus. There’s something fascinating about what students are like today and what students were like then… I try not to be a crusty old alumnus, but XPN is not what it was when I was there; it’s much more of a commercial format with few students really involved except as worker bees. Still, I have a lot of friends around Philly from those days. Heath Allen plays piano and composes, a friend from college. Last time I was there I went down to Bob and Barbara’s. They had a really great old-school organ trio [the late Nate Wiley & The Crowd Pleasers], which reminded me of some the little black jazz clubs in the ’70s. Clubs I used to go to, like the Aqua Lounge and Grendel’s Lair and the Bijou. I used to go to a club called Just Jazz downtown; I saw Earl Hines there, and McCoy Tyner played The Aqua Lounge, and all the old Coltrane band people. I look for these things. I’ve got a lot of friends who take me places. I have to say when I was just in Philly the last time, I was at this event at Penn that the urban studies people put together and sat with Mayor Nutter at dinner. I found out he used to be a disco DJ when he was in college, so we had a good time talking abut discoing and DJ-ing. I always find something; Philly is a city of deep and wide vernacular culture, and I think it is a city that a lot of Americans still forget exists. They think of it historically as far as the Continental Congress and Ben Franklin and all colonial era landscape, but they forget this is a major East Coast city filled with fascinating neighborhoods… and the Third World is there, but so is sort of the Old World and old Philly. It’s much more intimate to me than New York and much more warm and friendly than Washington. I really like Philly. I also like Baltimore, but I know Philly better, so when I come back I’m always exploring and learning what’s happening now and it’s a pleasure.

PHAWKER: Just to clarify, what was the time frame of your tenure in Philly? You came in ‘68, correct?

NICK SPITZER: I was a freshman in college in ’68. I started hosting shows on XPN in the spring of ‘69. In the summer of ‘70, a bunch of other students and myself raised the money from our listeners and got XPN away from being a student activity and on the air all summer full time. By the time I graduated I think XPN had become more widely known in the city because we were a real station. I started at MMR in the summer of ‘72, I did MMR for 2 years, reaching just the beginning of ‘74. Then I took off on my big Jack Kerouac–meets Woody Guthrie trip across America for about eight months, traveling to visit where Doc Watson lived and where Native American music was — Cajun, jazz, cowboy music — traveled all across the country looking for music and local scenes, hanging out before I went to anthropology grad school. I went to grad school in Austin in the ’70s when alt-country was starting to build up, it was called “cosmic cowboy” music, “redneck rock” or “hippie country.” I worked on KOKE-FM (of all names) which was the station for the beginning of the Austin scene. It was mix of roots, rock, barrelhouse blues, Western swing, straight country, “crooked” country and Tejano music… all during the time of the return of Willie Nelson and Waylon Jennings from Nashville. A lot of people came out of it: Marcia Ball, Joe Ely, Butch Hancock… and even Janis Joplin had spent time in Austin earlier—all that was part of the Austin scene. I did that from ‘74-’78 then I moved to Louisiana where I had been doing field work in Louisiana Afro-French Creole zydeco worlds, and I finished a dissertation on zydeco. I started working for the state of Louisiana as a folklorist; I did that for a bunch of years before I split in ‘85 and went to Washington, worked at the Smithsonian for 10 years and I came back to Louisiana in ‘97 to be based in New Orleans and started Routes. If I had started the program right after college (which I wanted to do) instead of going to MMR, it would have been called American “Roots.” In other words, I had more of a deep roots, old-school, perhaps nostalgic vision of tradition, cultures and music at that time. Twenty-five years later I had been out being a folklorist and a public servant and then working at the Smithsonian, and I went to NPR for a while, did a bunch of features in the ’90s for All Things Considered. I think I came to the conclusion that deep roots music was also Routes: people from the Delta went to Chicago to make city blues and electrify; and people from Ferriday, Louisiana, like Jerry Lee Lewis, went up to Memphis to make rock and roll; people in America were and are in motion. Ray Charles had grown up with the blues and jazz and gospel music, and he loved country music too, but then he invented soul. So I just felt like the transformation of culture in people and their migrations in music were as important as what was preserved from the past. A lot of these transformations were kind of a preservation in that they had a kind of continuity built in to the changes of style and identification. So I really couldn’t do this show as being about the change as much as the continuities–as Routes–until I myself traveled back and resettled in New Orleans and started putting it together, and we’re now in our 11th year. I think the fact that WHYY is one of the most important stations to us, not only because Philly is a large market, but they’re essentially doing news and information and they’re treating our stuff as equally valuable–and hopefully enjoyable – for listeners. And it’s also Philly… which I think has a wonderful, eclectic, fairly high-consciousness about music. It’s like Boston. I think these are better music cities–especially for the radio–that people are generally more aware of music than in New York and Washington in certain ways, where the media is all slammed into categories. It might not be the ’70s that I revered the most, but there’s a lot of good things happening. I feel like my XPN and MMR experiences in life really shaped what Routes is. It has the journey of underground radio… it has the eclecticism of what college radio was when I was there in the sense of finding out something new… and often what is new could be old. It could be R&B, it could be bluegrass, it could be great jazz, it could be rock and roll. But Philly is a really good place for that, but I wouldn’t say it’s in my nature – but it is in my nurture.

PHAWKER: WMMR back in those days, was it really that free-form as a DJ? Were you really able to pick what records you played on the air?

NICK SPITZER: Well, it wasn’t as free-form as XPN, but it had 20 times the audience at the time. It was pretty free-form; I was doing afternoon drive and playing everything from Sly and the Family Stone segued to Ornette Coleman. We were playing Tammy Wynette doing country, she had killer jazzy version of “Ode to Billy Joe,” segued to Ray Charles singing “You are My Sunshine” as a soul song.

PHAWKER: This is on MMR? You’re blowing my mind with this playlist.

NICK SPITZER: MMR then had an influence on how Routes is done today. In the afternoon drive time you played boogie for all those commuters headed home. For me that meant the Chicago blues of Howlin’ Wolf or the Rolling Stones from the rock side of blues influence, rather than the British hair bands like Foghat and the ELOs and the more synthetic Yes. The MMR management wanted my program to be more up-tempo, with current pop rock, and less country and “nostalgia music” as they called it. But my numbers were really good at MMR. These increasingly mainstream underground stations were on frequencies with the new FM stereo signals that had been inhabited by easy listening or classical. And those formats were less and less where the energy and money was at that time. So that’s why all the then-young hippies were able to get on the radio and have community-based programs or educational radio. When these new progressive rock-underground stations got more popular the advertising moved from head shops, book stores or places that sold waterbeds, and started to become ads for Miller Beer and pimple cream. Suddenly we were showing up on the marketing charts. Then the pressure started from the record companies — the day someone walked in the door and told me I had to play “A Horse with No Name” by America was the day I knew I probably wouldn’t stay at MMR for the rest of my life — or even six more months. We were getting pressure from local concert promoters and the record companies. It was getting depressing and discouraging but no one really came after me in a big way until finally my boss said he was re-assigning me to production and putting me on the all night shift; which if you’ve been doing drive time, that’s like being sent to Siberia. Right out of college doing the all-night show I would have been happy as a clam, but two years down the road this pissed me off. The memories are fun though. I went to a lot of promotional parties that were like that scene in Spinal Tap, and I have fond recollections of a lot of this stuff. And don’t get me wrong, I liked a lot of the people in the Philly music biz of the era. But in the end it was clear the freedom we had on the air at MMR was ending.

PHAWKER: Roughly what year was this that it went from what it was to what it’s become now?

NICK SPITZER: It was happening in late ’73, and then they codified it throughout the later ’70s. They really started picking people to host that would playing records off the playlists. You were getting artists on the air that were more part of commercial record deals, or because they were playing the Spectrum and what have you. Some were good, but the question was who is backing these bands? I was particularly sensitive to it. Let’s face it, I was an XPN guy and a former Penn student that was interested in American culture records. I didn’t see myself inside the music industry world; I saw myself as someone who played music on the radio from my artistic perspective, not someone who played tracks chosen by somebody else. That’s what led me to leave and go out to the honky tonks and the bars, the churches and streets of America searching for music and community… and that led me eventually to Louisiana. It was a year after Philly, 1975, that I started working my way through grad school by hosting at KOKE-FM. It was a much smaller operation than MMR in terms of listenership, and had no commercial pressure at all. It was great, exactly what I wanted to do. Later I did NPR cultural features scripted and post-produced for the news. But when I left Austin, I kind of abandoned personally hosting radio from roughly ‘78 until I started American Routes in ‘98. So that gives you about 20 lost years of not hosting a show. I did documentaries at Radio Smithsonian, and I did those NPR features, and I did a live concert stage radio program at Carnegie Hall called Folk Masters. The live on NPR Fourth of July shows during the Clinton administration happened on the mall. But as far as hosting a mixed, eclectic Americanist radio program, that didn’t happen again really until 1998 when I started Routes. No XPN, no MMR, no KOKE FM…no American Routes. I couldn’t have gone back to something like radio hosting and music mixing without knowing how to craft a set list that people would enjoy. It could be sonically great, but it also had to be semantically engaging. A part of this is that you have to entertain and I’m totally for that. You can’t just give them information; you have to have a beat, a flow, a melody, a message, a symbolic mood. It has to be interesting and engaging. People are taken to a different level with the history of genres and artists, and the American issue around pluralism and shared music styles are things we try to address with the mix. I love that, that’s my heart. But in the end I also like the body and soul side of making a music mix for people that want to tap their feet, wanna live in that music world, whether they are driving their car or at home doing chores or eating dinner. I want to entertain, and I first learned how to do that at XPN and MMR really.

NICK SPITZER: It was happening in late ’73, and then they codified it throughout the later ’70s. They really started picking people to host that would playing records off the playlists. You were getting artists on the air that were more part of commercial record deals, or because they were playing the Spectrum and what have you. Some were good, but the question was who is backing these bands? I was particularly sensitive to it. Let’s face it, I was an XPN guy and a former Penn student that was interested in American culture records. I didn’t see myself inside the music industry world; I saw myself as someone who played music on the radio from my artistic perspective, not someone who played tracks chosen by somebody else. That’s what led me to leave and go out to the honky tonks and the bars, the churches and streets of America searching for music and community… and that led me eventually to Louisiana. It was a year after Philly, 1975, that I started working my way through grad school by hosting at KOKE-FM. It was a much smaller operation than MMR in terms of listenership, and had no commercial pressure at all. It was great, exactly what I wanted to do. Later I did NPR cultural features scripted and post-produced for the news. But when I left Austin, I kind of abandoned personally hosting radio from roughly ‘78 until I started American Routes in ‘98. So that gives you about 20 lost years of not hosting a show. I did documentaries at Radio Smithsonian, and I did those NPR features, and I did a live concert stage radio program at Carnegie Hall called Folk Masters. The live on NPR Fourth of July shows during the Clinton administration happened on the mall. But as far as hosting a mixed, eclectic Americanist radio program, that didn’t happen again really until 1998 when I started Routes. No XPN, no MMR, no KOKE FM…no American Routes. I couldn’t have gone back to something like radio hosting and music mixing without knowing how to craft a set list that people would enjoy. It could be sonically great, but it also had to be semantically engaging. A part of this is that you have to entertain and I’m totally for that. You can’t just give them information; you have to have a beat, a flow, a melody, a message, a symbolic mood. It has to be interesting and engaging. People are taken to a different level with the history of genres and artists, and the American issue around pluralism and shared music styles are things we try to address with the mix. I love that, that’s my heart. But in the end I also like the body and soul side of making a music mix for people that want to tap their feet, wanna live in that music world, whether they are driving their car or at home doing chores or eating dinner. I want to entertain, and I first learned how to do that at XPN and MMR really.

PHAWKER: Where did the impetus come from to be a folklorist? Did it precede your college days or was post-college?

NICK SPITZER: I think it did precede my college days in the sense that I had older parents — both only children — who were very nostalgic for their personal pasts. My father came of age in early Weimar Germany. My mother was from an old First Family of Virginia–an abolitionist wing I should add. They both lamented the loss of grand civilizations in their formative lives, and I grew up with the sense of that loss, but also with an Americanist vision of peoples and possibilities of many cultures. I asked myself, “Where are the country music people?” “Where is the blues played?” “What happened to the Native Americans and their communities?” “What holds our eclectic country together?” I channeled that quest for the pluribus and the unum through the energy of the ’60s and ’70s, and wondered: “How do we recover some of these people, these voices, this music from the recent and deeper past?” I didn’t grow up loving Elvis Presley — that wasn’t cool when I listened to rock and roll — but you know I began listening back to all that R&B and rockabilly and saying, shit this is great stuff. And you know there’s certain artists that connect you back to those things, to certain rock, pop and folk artists. Dylan connects you to Woody Guthrie, and the Rolling Stones connect you back to Muddy Waters, and the Beach Boys connect you back to Chuck Berry and others. So I was a curious person. I always followed the line back, and followed those iconic players deeper into country, blues, and soul, and gospel, and jazz, and other universes. In school I realized didn’t want to be an accountant or a finance person at Wharton; I got into anthropology and I also realized I wasn’t going to study the trade routes of Melanesia. I wasn’t going to Africa to study the cattle wealth of the Nuer. I wanted to know more about America — the cultures here in a society where tradition and modernity were in constant and complex contact. It was both my culture and not my culture that made me feel like an American, and that just kept building for me. A radio station like XPN allowed one access to a really great record collection inclusive of these unities and diversities, and gave me the creative space to develop the ability to reach out and broadcast tall these aesthetics sounds into a stream of resonant segues. Later after WMMR, when I finally went out on the road, my impetus was to find the places in America I only knew from books or records: the upland South Appalachian region, the Mississippi Delta and French Louisiana, out to the West of cowboys, Native American sacred spots, all to find what that music and culture was. I’ve circled back a few times since then and it’s a lifelong impulse to try and engage other cultures and feel that it’s partly both your own and somebody else’s. It’s the American story that we share things and the way we distinguish ourselves as a people ethnically, regionally, musically, religiously, linguistically. So I’m still a folklorist and some of the same impulses animate me today. I’m just excited to be able to do this show and bring it back to many more people in a new way.

PHAWKER: There are some that would say that this country was founded on genocide and is essentially built on the bones of Native Americans. Do you think there’s any credence to that point of view, or is that really just part of the general turning over and churning of cultures and ethnicities — as has happened in Europe and all over the world’

NICK SPITZER: It’s a lot easier in retrospect with current values and ethics and the position we are in, removed  from some of the harder edges in life in colonial times to look back and see that and say “Ain’t that a shame!” Because there’s a deep sorrow, not just the genocide of the Native American peoples but the enslavement of African-Americans and indentured servants from Europe and every other exploitative thing. There’s no question that much in our history is reprehensible in current terms. But we live in the present and hope for a better future. I think it’s important to recognize the problems that have been created by the forces of history and culture and class and race and the damaging use of the landscape and the use of other people as resources. At the same time we can marvel at the fact that Thomas Jefferson himself was an amateur ethnographer in documenting Indian languages. There were roughly 400 Indian languages that he counted before he became president. We marvel at people who had larger visions of things like that — though we know he was a slaveholder. In the current moment, it is important to recognize the pains, but also recognize how people have grown together to create music like jazz, blues, country, soul, and rock and roll. You can tell the hard truths about American life, but you can do some of it through beauty, some of it through how people have created newness out of old parts, even those that have pain associated with them. Here in New Orleans, we can dwell about how bad our levee system was and how we have to fix it. We can also focus on the fact that culture is now at the center of our recovery. Neighborhood groups, the same social aide and pleasure clubs that helped African-Americans survive through the beginnings of Jim Crow and throughout the 20th century, and the social setting for the beginning of jazz. The most repressive period in New Orleans created some of the greatest music and cultural expression. So I start with the fact that we’re here and it’s now, and we’ve got a future ahead of us. What are we gonna do, more than only dwelling on every pain of any particular past? That said, I think people must go through some of those things — particular groups with particular pasts — and we all should be aware of them, but I feel like our job is to deal with the present and the future more than focus on how some music arrived because of self-deprivation. I think we have to see the human spirit creating and moving forward and trying to transcend those things, so we have some hope ourselves for the future.

from some of the harder edges in life in colonial times to look back and see that and say “Ain’t that a shame!” Because there’s a deep sorrow, not just the genocide of the Native American peoples but the enslavement of African-Americans and indentured servants from Europe and every other exploitative thing. There’s no question that much in our history is reprehensible in current terms. But we live in the present and hope for a better future. I think it’s important to recognize the problems that have been created by the forces of history and culture and class and race and the damaging use of the landscape and the use of other people as resources. At the same time we can marvel at the fact that Thomas Jefferson himself was an amateur ethnographer in documenting Indian languages. There were roughly 400 Indian languages that he counted before he became president. We marvel at people who had larger visions of things like that — though we know he was a slaveholder. In the current moment, it is important to recognize the pains, but also recognize how people have grown together to create music like jazz, blues, country, soul, and rock and roll. You can tell the hard truths about American life, but you can do some of it through beauty, some of it through how people have created newness out of old parts, even those that have pain associated with them. Here in New Orleans, we can dwell about how bad our levee system was and how we have to fix it. We can also focus on the fact that culture is now at the center of our recovery. Neighborhood groups, the same social aide and pleasure clubs that helped African-Americans survive through the beginnings of Jim Crow and throughout the 20th century, and the social setting for the beginning of jazz. The most repressive period in New Orleans created some of the greatest music and cultural expression. So I start with the fact that we’re here and it’s now, and we’ve got a future ahead of us. What are we gonna do, more than only dwelling on every pain of any particular past? That said, I think people must go through some of those things — particular groups with particular pasts — and we all should be aware of them, but I feel like our job is to deal with the present and the future more than focus on how some music arrived because of self-deprivation. I think we have to see the human spirit creating and moving forward and trying to transcend those things, so we have some hope ourselves for the future.

PHAWKER: As you may or may not know, Harry Shearer has been using his radio shows as an occasional forum for getting the word out that a lot of the fault for Katrina lies with the Army Corps of Engineers, and I think the general perception of most Americans is that the flooding of New Orleans is the fault of New Orleans but it’s simply not true. I’m wondering what your thoughts are on that.

NICK SPITZER: A lot of people said, “Well, New Orleans’ antiquity is rickety and it’s not the best location for a city,” but you know, what is the best location for a city? The place is meaningful, the past is meaningful, and we’re not going to move New Orleans. Are there legacies in New Orleans that are not so strong? Sure, if we’re talking in historic racism and provincialism, if we’re talking weak public governments and institutions — I don’t think you’ll find a majority of citizens here that endorse those things. But they have emerged from colonial history and the battle of the frontier that produced this place, but the flipside of the cultural history is it being the place where jazz began. It’s a place where the cuisine has the whole world interested in tasting; and it’s the place where the building arts are phenomenal throughout the city. It wasn’t New Orleans’ antiquity in terms of music and food that did it in. The older footprint of the city built on the natural high ground didn’t flood. The flooding occurred in areas that were developed through modernity, pushed in part by developers creating newly drained landscapes and building suburban brick houses on concrete slabs. Wood homes in low ground more often rose on piers. So I say it was our bad modernity rather than our well-adapted antiquity that did us in. I do believe that the Army Corps of Engineers has a lot of responsibility here. There’s no question that the history of the place, because of its divisions between African and European and classes, did not have the same sense of public good that you have in Philly. By comparison Philadelphia is a more progressive city with a lot of major civic institutions. What did New Orleans produce? Not industry or science, or democracy. It produced jazz. I think that’s a pretty important civic institution for the whole world. So we might not have succeeded in some of the standard notions of democracy and infrastructure, but we have added a major lesson in cultural mingling as presented through an art-style. So I don’t think you can blame individuals or even people necessarily as a group for all those things. The Federal presence was supposed to be the presence of progress and modernity for the very infrastructure that failed us. It was that system more than anything that broke down. It was levees built to poor plans — often not even built to spec within those poor plans — that were never supposed to give way. Well, they gave way to high water that never topped them. So, I feel like a lot it does go back to the Corps. As for location, why do people live in L.A. with earthquakes? Why do people live in Venice with its occasional floods and daily water? Why does anybody stay anywhere? We do it partly because we care about our communities and our cultures. I think that’s a very profound attachment anywhere, but it’s particularly strong here. Think of us as a vernacular Venice of jazz and R & B.

NICK SPITZER: A lot of people said, “Well, New Orleans’ antiquity is rickety and it’s not the best location for a city,” but you know, what is the best location for a city? The place is meaningful, the past is meaningful, and we’re not going to move New Orleans. Are there legacies in New Orleans that are not so strong? Sure, if we’re talking in historic racism and provincialism, if we’re talking weak public governments and institutions — I don’t think you’ll find a majority of citizens here that endorse those things. But they have emerged from colonial history and the battle of the frontier that produced this place, but the flipside of the cultural history is it being the place where jazz began. It’s a place where the cuisine has the whole world interested in tasting; and it’s the place where the building arts are phenomenal throughout the city. It wasn’t New Orleans’ antiquity in terms of music and food that did it in. The older footprint of the city built on the natural high ground didn’t flood. The flooding occurred in areas that were developed through modernity, pushed in part by developers creating newly drained landscapes and building suburban brick houses on concrete slabs. Wood homes in low ground more often rose on piers. So I say it was our bad modernity rather than our well-adapted antiquity that did us in. I do believe that the Army Corps of Engineers has a lot of responsibility here. There’s no question that the history of the place, because of its divisions between African and European and classes, did not have the same sense of public good that you have in Philly. By comparison Philadelphia is a more progressive city with a lot of major civic institutions. What did New Orleans produce? Not industry or science, or democracy. It produced jazz. I think that’s a pretty important civic institution for the whole world. So we might not have succeeded in some of the standard notions of democracy and infrastructure, but we have added a major lesson in cultural mingling as presented through an art-style. So I don’t think you can blame individuals or even people necessarily as a group for all those things. The Federal presence was supposed to be the presence of progress and modernity for the very infrastructure that failed us. It was that system more than anything that broke down. It was levees built to poor plans — often not even built to spec within those poor plans — that were never supposed to give way. Well, they gave way to high water that never topped them. So, I feel like a lot it does go back to the Corps. As for location, why do people live in L.A. with earthquakes? Why do people live in Venice with its occasional floods and daily water? Why does anybody stay anywhere? We do it partly because we care about our communities and our cultures. I think that’s a very profound attachment anywhere, but it’s particularly strong here. Think of us as a vernacular Venice of jazz and R & B.

PHAWKER: Where is New Orleans in terms of a recovery on a scale of 0 to 100 percent?

NICK SPITZER: If I put it on a scale I’d say we’re probably at 75, 80 percent. It’s becoming a different city. It’s getting smaller, there’s a huge influx of intelligentsia, artists, environmentalists, writers and students. What we have is this giant brain gain. People that are here, the former locals, the natives, and new arrivees all want to be here. So there’s an energy in the city that I think it did not have prior to Katrina that is driving the recovery. That said, there are still long-term political and economic issues here that hold back the recovery. Though, as you may know, New Orleans actually has an unemployment rate about 2 ½ points better than the national average, partly because the recovery is so much about recovery employment and the rebuild. And a lot of people are coming here from the building trades and all these other things that I mentioned. There are areas of the city, particularly in the 9th Ward and New Orleans East, that are hard to see recovering any time soon. On the other side of it there are high ground areas that renovations have been occurring in, that housing and new interesting stores and businesses have been filling in the landscape. As Dickens said, this the best of times and the worst of times. I think some of the best we’re seeing is stuff nobody really imagined happening here — better schools, better playgrounds, more civic responsibility, and a more engaged citizenry. As for the worst of times: the continuing empty areas, the weed-covered lots, broken and molded houses that will not be brought back from the vastness of the destruction, or make it through the red tape of FEMA. But, as an accentuater of the positive, I am hopeful we are making substantial progress. It’s just not always obvious on a daily basis.

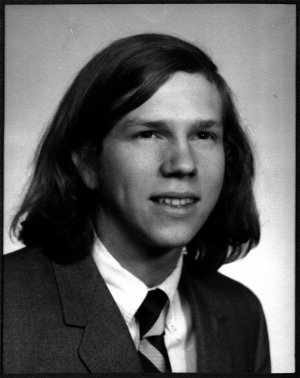

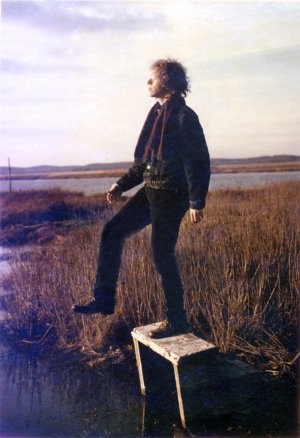

EDITOR’S NOTE: This was intended as an artsy amalgam of Young Nick and Current Nick, but the end result seemed to raise more questions than it answered. Hence its location at the bottom of the page. Just wanted to clear the air because some readers have inquired why we ran an illustration of Nick tooling around with an inappropriately young girlfriend or why is Nick taking a road trip with Nick Drake. Hope this answers your questions.