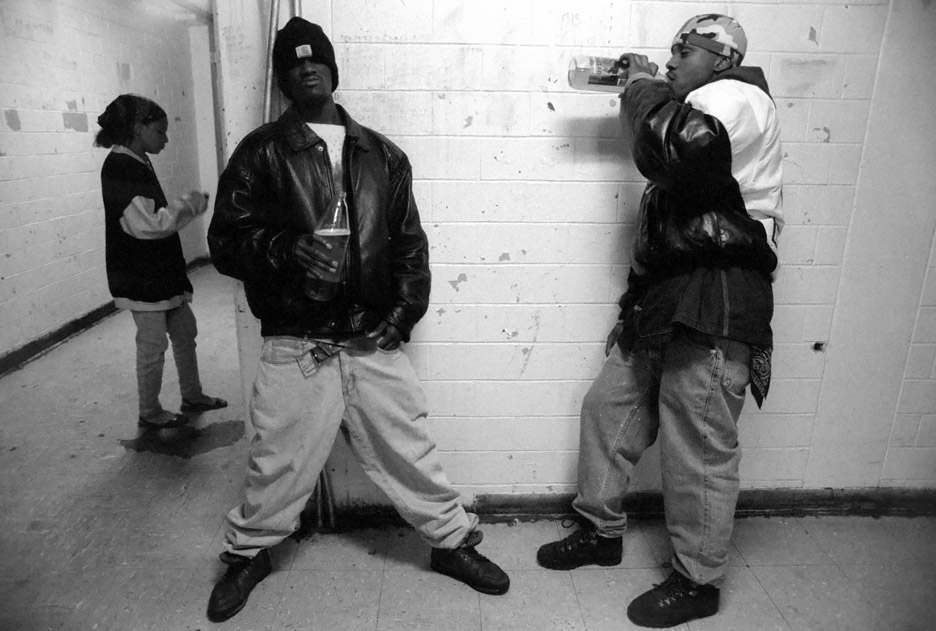

BY JEFF DEENEY TODAY I SAW new black magic marker tags scrawled on the sidewalk outside Mantua Hall. “Tre Six Gangstas,” read one, “36th Street Mafia” read another. There’s a ledge outside the front doors to the housing project tall enough to sit on, and there were seven or eight Tre Six boys kicking back on the ledge and mobbed on the steps leading to the front door. It was early Friday evening, so I assumed they were getting ready to serve the payday party crowd that would start rolling through at any minute. One of the boys had shoulder length dreads, an oversized black Dickies outfit and was playing with his Sidekick, flipping the top open and shut. On the third time that he flicked the swivel screen shut he spun the gadget 360 degrees in the palm of his hand. When I mounted the steps my foot landed right next to where he sat; he stopped playing with his Sidekick and looked up at me.

BY JEFF DEENEY TODAY I SAW new black magic marker tags scrawled on the sidewalk outside Mantua Hall. “Tre Six Gangstas,” read one, “36th Street Mafia” read another. There’s a ledge outside the front doors to the housing project tall enough to sit on, and there were seven or eight Tre Six boys kicking back on the ledge and mobbed on the steps leading to the front door. It was early Friday evening, so I assumed they were getting ready to serve the payday party crowd that would start rolling through at any minute. One of the boys had shoulder length dreads, an oversized black Dickies outfit and was playing with his Sidekick, flipping the top open and shut. On the third time that he flicked the swivel screen shut he spun the gadget 360 degrees in the palm of his hand. When I mounted the steps my foot landed right next to where he sat; he stopped playing with his Sidekick and looked up at me.

This is how you walk through a crowd of project boys: keep your back straight and your pace brisk. Don’t look tired, even if you are. Keep your eyes in front of you, unless someone is trying to make eye contact; if someone tries to make eye contact, return it and hold it. When you get taunted, ignore it or laugh it off. Never look wounded or threatened. If you are greeted, even in jest, return the greeting. Shout it back — don’t let your voice falter. Use uncertainty to your advantage, they think you’re probably not a cop. But you might be. As long as you come across as fearless, they won’t know for sure. A good gangster will err on the side of caution, eyeing you warily but letting you pass without harassment.

The man at the front desk in a white tee and busted-up teeth asks more questions than usual. It’s Friday  evening; a white guy isn’t going to just stroll into a high-rise without getting grilled. Through the bulletproof Plexiglas I can barely hear him. Who you here to see? What apartment? How long you gonna be? Let me see your identification.

evening; a white guy isn’t going to just stroll into a high-rise without getting grilled. Through the bulletproof Plexiglas I can barely hear him. Who you here to see? What apartment? How long you gonna be? Let me see your identification.

The lobby is filled with blunt smoke so thick it makes my eyes water. There’s another crew of Tre Six boys in an alcove by the laundry room. These are young teenagers; wild, feral children. Their narrowed, reddened eyes peer out from under sweatshirt hoods. Their loud banter and grab-ass games stop dead when they see me; they retreat silently into darkened corners where light bulbs have been smashed to provide cover. Two mothers and their screaming children flank me, waiting for the elevator. I can feel the Tre Six boys still watching me, though I can’t see them and don’t want to turn my head in their direction to verify that they are. It’s never wise to invite trouble.

Sometimes it takes 15 minutes for the elevator to arrive. I cross my fingers and hope that tonight it comes quick.

When the elevator opens, a tall and slender woman wearing Muslim garb emerges. She’s covered from head to toe, only her eyes showing from under the fabric wrapping her face. The front door opens behind us and a gust of wind fills the folds of her abaya, making her look like a bilious black ghost as she floats through the room’s haze.

Upstairs I’m greeted by the still-shrieking smoke alarm. The sound hits me like an open-handed blow when I step off the elevator. A minute later, it shrieks again, just like it shrieked when I was here two weeks ago. It’s going on six weeks now that the alarm has been sounding, around the clock. It gives the impression that Mantua Hall is a place frozen in time and totally forgotten, where nothing changes except to decay.

Its impending implosion can’t come soon enough.

AFTERWORD: The high rise public housing project is arguably the greatest failure of modern urban planning. It became an American icon, if a totally shameful one, as the misery of living in poverty in cities around the country was defined by the almost mythic horror stories emanating from housing projects in the ’80s and ’90s. In the early ’90s I was a young drug addict mostly failing out of the University of Chicago. On a couple occasions I went with a neighborhood oldhead to cop dope at the Robert Taylor Homes, possibly the most notorious housing project in the country at that time. The near total chaos that raged there was one of my first encounters with desperate urban poverty and the powerful impression it left on me would later become a driver for my involvement in the social justice movement. The Robert Taylor Homes are no longer there; they were thankfully torn down, as was Mantua Hall not long after this narrative was written. The families living in Mantua Hall were relocated to scatter-site housing in communities of their choice; from what I understand the relocation effort went smoothly and most families are very happy with their new homes.

I am often asked when I tell people about my job, how do you manage to work somewhere like Mantua Hall without getting hurt? Sometimes there is a more general follow up question about how to safely navigate bad (black?) neighborhoods (as a white yuppie). I feel like this is a loaded line of questioning that makes a lot of assumptions about poor neighborhoods. There have been some rare moments in my work like this time at Mantua Hall where I felt putting up a hard façade was necessary. The reason for this was that a social worker at the agency I worked for had just been assaulted there and another had been so threatened she fled without making contact with the client. We were told to be on guard when doing home visits at Mantua Hall, and the situation I walked into that evening was setting off danger alerts in my street senses. But the bottom line is that the hard façade was a bluff, and if one of the Tre Six kids had stepped to me and called it I would have been completely fucked.

What is the best way to navigate a bad neighborhood? Make friends there. It’s amazing how less threatening even the most notorious blocks becomes when you are able to put names to faces and know peoples’ stories. My experience is that even on the city’s most dangerous blocks there are honest, hard working families who don’t want anything to do with the nonsense, and most of them are totally cool with somebody like me working on their block. The best way for a social worker to do their job is to build alliances with the people living in the neighborhood who are willing to work in partnership with them towards a common goal of improving their community.