MOON (2009, directed by Duncan Jones, 93 minutes, U.K.)

MOON (2009, directed by Duncan Jones, 93 minutes, U.K.)

THE HURT LOCKER (2008, directed by Kathryn Bigelow, 131 minutes, U.S.)

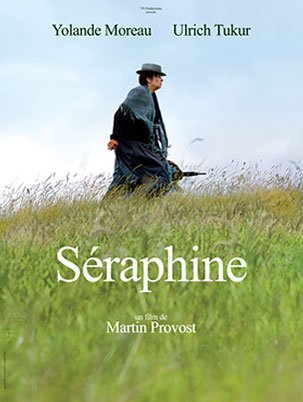

SERAPHINE (2008, directed by Martin Provost, 121 minutes, France)

BY DAN BUSKIRK FILM CRITIC

I was trying to recommend an off-the-beaten-track sci-fi film from the last few years for a friend and I was coming up blank. It struck me that nearly all sci-fi films are built to be blockbusters these days, there is no small budget sci-fi just as there is no low budget super hero films, the genre is completely given over to spectacle. This makes Moon, the debut of director Zowie Bowie (okay, David’s son does go by the name Duncan Jones these days) a real anomaly, a space story built on ideas rather than effects.

Lonely spacemen being somewhat a theme in this family (I had to Google to discover that numerous reviewers had already beaten me in quoting the lyric “Planet Earth is Blue and There’s Nothing I Can Do”), director Jones presents Sam Rockwell as astronaut Sam Bell, a lone spaceman employed to harvest helium on the far side of the moon. With only a computer named GERTIE (with Kevin Spacey’s HAL-like voice) to keep him company, Sam sleepwalks through his work day, yearning to return to his wife and young daughter on Earth. He’s on the verge of losing his marbles when, just weeks away from finishing his tour of duty, he finds another human on the moon’s surface, a battered version of himself.

If you’re going to be stuck viewing a movie with one actor you could do worse than Sam Rockwell, he’s unusually amiable yet his character’s genial nature often hide something is not quite balanced at their core. With a second Sam wandering around the moonbase, the film starts to lose track of which Sam’s story is being told and later begins to ponder the nature of humanity as well.

Underneath all its futuristic setting what ultimately unnerves director Jones is the way jobs dehumanize us. Sam may know he being screwed by the company that sent him to the dark side of the moon but he’s powerless to lash back at them, they’re as distant and untouchable as GERTIE’s monotone voice. The film’s ending is not vague although it presents the possibility of many destinies for Sam, none of which would keep the company from extending his cruel fate to another guy, a guy just like him.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Another sad and alienated soul is at the center of The Hurt Locker, the most successful and least openly political  of the string of films made about the war in Iraq. Staff Sergeant William James (JeremyRenner) is the new defusing expert in an army bomb squad with two right hand men, the cautious Sanborn (Anthony Mackie) and the frazzled Eldridge (Brian Geraghty ). You would probably want your bomb defusing specialist to be unshakable, but Sgt. James demeanor begs the line between “cool” and “reckless” as he doggedly tries to figure out the secret behind each bomb while his team sweats bullets watching the crowds grow larger and more ominous. It’s just one month before the squadron gets to rotate home, and James’ cavalier cockiness slowly wins over the soldiers at the same time that his psyche begins to spin loose from its bearings.

of the string of films made about the war in Iraq. Staff Sergeant William James (JeremyRenner) is the new defusing expert in an army bomb squad with two right hand men, the cautious Sanborn (Anthony Mackie) and the frazzled Eldridge (Brian Geraghty ). You would probably want your bomb defusing specialist to be unshakable, but Sgt. James demeanor begs the line between “cool” and “reckless” as he doggedly tries to figure out the secret behind each bomb while his team sweats bullets watching the crowds grow larger and more ominous. It’s just one month before the squadron gets to rotate home, and James’ cavalier cockiness slowly wins over the soldiers at the same time that his psyche begins to spin loose from its bearings.

Director Kathryn Bigelow hasn’t scored like this in over a decade, reminding us how much we thrilled to her vampire western Near Dark and the surf robber goofball classic Point Break. The Hurt Locker is her most adult and concise work yet, keeping its focus on the lonely adrenaline addict James as he drags his partners closer and closer to the flames. It’s a film that rarely lets up; even though I might have shortened its length a bit (Bigelow’s plots are never as tightly spun as her action sequences) Hurt Locker’s tension rarely ebbs as it spends much of its running time in various countdowns to disaster. You know James’ luck can’t hold out forever but you won’t be able to guess which way the shrapnel is going to fly.

Jeremy Renner, whose toughness, pug nose and fireplug physique resemble the young James Cagney, has mostly been on the periphery in films since playing serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer is the ghoulish film Dahmer. As in Dahmer, he almost passes as a normal guy, if only his eyes weren’t so cold. He wears that ready-to-die iciness as a defense, where it reveals itself as both a blessing and curse. The Hurt Locker’s sad portrait shows that of all the things that war steals from men, the biggest loss is that it keeps them from feeling whole anywhere but on the battlefield.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Looking at the lumpen image of Yolande Moreau on the posters for the new French artist biopic Seraphine I found myself reacting much like her clueless contemporaries: did I really care to pay attention to this dowdy cleaning woman turned painter? The film’s disdainful art buyers may never wise up to the artists’s ravenous plants and flowers but it would be equally as foolish to write off this unvarnished look at the French naïve painter of the early twentieth century. This Best Picture winner at the 2009 Cesar Awards (often called the French Oscar) Seraphine is the most thoughtful film on painting made this decade. In a bravely raw performance, Yolande Moreau’s takes her Seraphine on quite a trip, at first melting into the woodwork in the presence of others and slowly emerging into a bit of a wounded monster, unable to deal with the acclaim, judgment and power that emanates from her painting. The much-covered recent meltdown of Britain’s Got Talent contestant Susan Boyle gives you an idea of the scenario, to go from the mousey shadows to the spotlight can be as treacherous as it is triumphant.

Looking at the lumpen image of Yolande Moreau on the posters for the new French artist biopic Seraphine I found myself reacting much like her clueless contemporaries: did I really care to pay attention to this dowdy cleaning woman turned painter? The film’s disdainful art buyers may never wise up to the artists’s ravenous plants and flowers but it would be equally as foolish to write off this unvarnished look at the French naïve painter of the early twentieth century. This Best Picture winner at the 2009 Cesar Awards (often called the French Oscar) Seraphine is the most thoughtful film on painting made this decade. In a bravely raw performance, Yolande Moreau’s takes her Seraphine on quite a trip, at first melting into the woodwork in the presence of others and slowly emerging into a bit of a wounded monster, unable to deal with the acclaim, judgment and power that emanates from her painting. The much-covered recent meltdown of Britain’s Got Talent contestant Susan Boyle gives you an idea of the scenario, to go from the mousey shadows to the spotlight can be as treacherous as it is triumphant.

Born Seraphine Louis in 1864, her mother died when she was one year old and her father died by the time she was seven. From there she was under her eldest sister’s care and later worked as a shepherdess, a domestic worker at a convent and as a housekeeper in a middle class household. The film begins there, just before she’s discovered by a German art dealer Wilhelm Uhde (Ulrich Tukur from Tom Cruise’s Valkerie and Soderbergh’s Solaris remake) in 1919 when Seraphine was fifty-three. By then she has already partially submerged into a world of her own creation, finding comfort in the nature and solitude around her and believing that her painting was guided by the hand of a guardian angel.

She paints with the same intensity in which she scrubs floors, grinding her own secret colors from plants she picks and singing ancient church hymns as she works. The paintings, in real life and in the recreations seen here, are awe-inspiring large canvases of surging, gasping, screaming blossoms that recall Van Gogh’s sunflowers in the way they leap off the flat canvases. We see her meet with potential buyers, holding these two-meter tall masterpieces in front of herself while her eyes peer nervously over the top. Ahead of her time, her clients don’t quite get it. One woman comments that the flowers are unnerving in their resemblance to teeming insects, “Oh yes, they frighten me too”Seraphine confides.

In the end, her imagination is too powerful for her to control, the power of her art opening opportunities that her fragile personality can’t navigate. She turns egotistical, needy, and delusional and finally collapses under the weight of her own talent. It’s a familiar arc for the artist biopic but Seraphine‘s lack of sentimentality and cheap spiritual uplift, not to mention Yolande Moreau’s unglamorous performance, bring the artist Seraphine to urgent life. It ends with a beautiful slow-building moment of acceptance that generously awards her tormented soul a moment of peace that tempers the mood of tragedy.