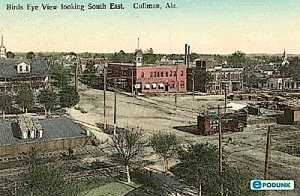

![]() BY AARON STELLA GAYDAR EDITOR Welcome friends to a very special edition of GAYDAR. I’ve just returned from visiting my family headquarters in the dirty, dirty south: Cullman, Alabama, to be exact. At the behest of the bossman, I will tell you all about it. If you have never been below the Mason Dixon, you would be well-advised to disabuse yourself of any romantic notions you might have about the South.

BY AARON STELLA GAYDAR EDITOR Welcome friends to a very special edition of GAYDAR. I’ve just returned from visiting my family headquarters in the dirty, dirty south: Cullman, Alabama, to be exact. At the behest of the bossman, I will tell you all about it. If you have never been below the Mason Dixon, you would be well-advised to disabuse yourself of any romantic notions you might have about the South.

Things have changed since Faulkner’s day, when the Land of Dixie was ripe with bucolic charm: rustic little hamlets scattered through field and vale, forests flourishing with pine and dogwood and the sweet scent of cornbread and pecan pie taking wing on humid breeze. It ain’t like that any more. Corporate America has had a field day down here: what used to be miles of rolling farmland has been replaced with strip-malls, fast food conglomerates, and lots and lots of mega-churches. (In fact, Cullman is in the Guinness world book of records for having the most churches contained within a county, numbering 365 churches altogether.) In short, much of non-urban Alabama is indistinguishable from the suburban blight of the North.

However, change has come to the South, even to Cullman, which has never been very hospitable to the idea. They now have their fair share of Internet café s in the heart of the city (pop. 18,000). But the change I am talking about is more significant than wedding the Internet to caffeine. For as long as I can recall, Cullman existed as a de facto whites-only zone for Alabamians. There is a major Ku Klux Klan presence in town. Back when I was still a boy, I remember driving home one summer night with my father behind the wheel. Up ahead, out of the darkness, came three figures brandishing torches by the side of the road. As we drew closer, we could make out their starch white coverings and the telltale steeples of their hoods. They were hailing cars down into a small clearing along side the road that bordered a dense grove of pine trees. As we passed the field I saw phalanxes of torch-bearing acolytes clothed in their ghostly garb.

have their fair share of Internet café s in the heart of the city (pop. 18,000). But the change I am talking about is more significant than wedding the Internet to caffeine. For as long as I can recall, Cullman existed as a de facto whites-only zone for Alabamians. There is a major Ku Klux Klan presence in town. Back when I was still a boy, I remember driving home one summer night with my father behind the wheel. Up ahead, out of the darkness, came three figures brandishing torches by the side of the road. As we drew closer, we could make out their starch white coverings and the telltale steeples of their hoods. They were hailing cars down into a small clearing along side the road that bordered a dense grove of pine trees. As we passed the field I saw phalanxes of torch-bearing acolytes clothed in their ghostly garb.

In some ways it’s hard to square that memory with the way things are in Cullman these days: The Mexican population has grown significantly over the last four years, as evidenced by the myriad of Mexican restaurants that have sprung up recently, and whereas in the past you would NEVER see a person of color behind the counter or cash registers of local businesses, today even the Verizon employs a multi-racial staff. Hell, the manager was black. Trust me, this is major progress for Cullman.

On the other hand, some things haven’t changed. Cullman is still situated in a dry county, and, ironically, has one of the highest rates of alcoholism in the state. And then there’s that pesky meth problem. I’m sure I don’t have to tell you that this is McCain-Palin country down here. For the most part, my family and I occupy separate camps on most issues. While I am definitely the ideological black sheep, we refuse to let animosity of any kind linger or to bear grudges. Call it peaceful disagreement. Despite our differences, we respect each other. They do differently than many Christians do when dealing with homosexuality: they love first, and check their judgments at the door. And I love them back with all my heart.

Being that I am the eldest sibling, and male, the onus still falls on me to set a good example. I was always expected to turn the other cheek whenever my sisters and I would verbally skirmish. And we skirmished all the time. Because my sister Clare was the youngest and most like me out of my two sisters, she knew exactly how to get my dander up. It deeply irked me that I couldn’t right hook my sisters whenever they got on my nerves. I think brothers are better able to deal with mounting aggressions by way of gut-punches and crotch-shots — whereas I had sisters. So I had to develop other means by which I could fight back. And so, I became a master practitioner of the dark art of scathing insult, able to trigger copious tears with a well-placed combination of unkind words.

Being that I am the eldest sibling, and male, the onus still falls on me to set a good example. I was always expected to turn the other cheek whenever my sisters and I would verbally skirmish. And we skirmished all the time. Because my sister Clare was the youngest and most like me out of my two sisters, she knew exactly how to get my dander up. It deeply irked me that I couldn’t right hook my sisters whenever they got on my nerves. I think brothers are better able to deal with mounting aggressions by way of gut-punches and crotch-shots — whereas I had sisters. So I had to develop other means by which I could fight back. And so, I became a master practitioner of the dark art of scathing insult, able to trigger copious tears with a well-placed combination of unkind words.

My sister Clare was the epitome of the conniving baby of the family: a master of manipulative tactics and heartstring tugging. These days, she has shifted her gift for gaining the upper hand toward achieving academic heights, and has, in my mind, become a sassy, sultry, however thoughtful young lady that will give any man a run for his money. My sister Miriam is the middle child and even though she is three years my junior, I look up to her as if she were the eldest. From an early age, she became somewhat of a sidekick to my mom, faithfully attending to her in every way. She wasn’t a suck-up; I don’t think mom could stand a suck-up anyway. I think a simpatico naturally developed. As she matured, Miriam seemed guided by a dauntless work ethic: She attends college, volunteers at a homeless shelter, runs triathlons, and still finds time to call periodically and tell me she loves me. After my mother divorced my father, she got right back on her feet, took a job working 50-60 hours a week to provide for the girls when my father did not. I cannot even begin to express the respect and admiration and love I feel for my mother, only, that I look to her as a well-spring of power and wisdom, and I am strong because of her.

Aside from our disagreements, the largeness of my family’s love trumps everything else. We say that we love each other before we get off the phone, and remind each other of it constantly when we’re together. You know, the nice thing about family is that you can get into heated discussions, let fly cruel invective, dig up family history that should never be unearthed and then weep together, and then everything just goes back to normal. There is a unique beauty in that you have to admit — catharsis and forgiveness. Jesus would be so proud. Still, being insufferably outspoken, and often taking for granted my family’s patience, I make a habit of quibbling at a whim; but a little tension’s healthy, right? How else is one to maintain that exquisite near-pain happiness we’ve all come to know and love.