![]()

NPR: Widely regarded as America’s greatest living songwriter, Bob Dylan has written and recorded some of the most influential and acclaimed music of the past century. With countless studio albums, compilations and live discs to his name in his nearly 50-year career, Dylan continues to produce new music that’s as vital as his earliest recordings, and still performs more than 100 concerts every year in what’s been called the “never-ending tour.” For the legions of fans who still can’t get enough, Dylan’s longtime label (Columbia Records) has been releasing a series of “bootleg” CDs from the singer — a vast collection of rare recordings and outtakes spanning five decades. The series began in 1991 with the first three bootleg volumes, covering the first 30 years of Dylan’s career. Now, 17 years later, Columbia is about to release the eighth volume. Tell Tale Signs covers Dylan’s past 20 years, a period that produced the albums Time Out of Mind, Love and Theft, Modern Times and Oh Mercy. Tell Tale Signs offers a rare glimpse into Dylan’s creative process, with alternate takes that show the evolution of his work, as his songs take shape lyrically and musically. Columbia recently gave listeners an early taste of Tell Tale Signs by offering the track “Dreamin’ of You” as a free download from Dylan’s Web site. You can also hear the song on the latest episode of All Songs Considered. Here, NPR Music offers a sneak preview of the entire two-disc set as a free stream. The album will be officially released in stores and online on Oct. 7. MORE

BOOK REVIEW: Maximum Bob

BY JONATHAN VALANIA Bob Dylan once sang that “Even the president of the United States sometimes must have to stand naked.” Physician, heal thyself. After 67 years on Earth, Dylan’s legend has been stripped to the bone and X-rayed ad nauseum by biographers and pundits probing the anatomy of his myth for distinguishing characteristics. There he is standing onstage at the Newport Folk Festival in 1965, the ghost of electricity howling in the bones of his face. There he is in a New York hotel room turning the Beatles on to grass, planting the seeds of Sgt. Pepper. There he is crucified at the Royal Albert Hall by an angry mob of ticket-holders calling him “Judas.” There he is on his motorcycle speeding into backbreaking oblivion, from which he would never quite return.

BY JONATHAN VALANIA Bob Dylan once sang that “Even the president of the United States sometimes must have to stand naked.” Physician, heal thyself. After 67 years on Earth, Dylan’s legend has been stripped to the bone and X-rayed ad nauseum by biographers and pundits probing the anatomy of his myth for distinguishing characteristics. There he is standing onstage at the Newport Folk Festival in 1965, the ghost of electricity howling in the bones of his face. There he is in a New York hotel room turning the Beatles on to grass, planting the seeds of Sgt. Pepper. There he is crucified at the Royal Albert Hall by an angry mob of ticket-holders calling him “Judas.” There he is on his motorcycle speeding into backbreaking oblivion, from which he would never quite return.

Anyone under 30 probably wonders what all the fuss is about. But there was a time when Dylan was the all-seeing  eye atop the pyramid of rock, a razor-thin, wild-haired visionary speaking in stoned parables and meth- riddles about the nature of transcendental consciousness from behind impenetrable black shades. His every utterance was scrutinized for prophetic import. His status as generational oracle was earned by a triumvirate of hallucinatory folk-rock albums — 1965’s Bringing It All Back Home and Highway 61 Revisited and 1966’s Blonde On Blonde — that he would spend the rest of his career simultaneously trying to live up to and live down, never quite succeeding on either count.

eye atop the pyramid of rock, a razor-thin, wild-haired visionary speaking in stoned parables and meth- riddles about the nature of transcendental consciousness from behind impenetrable black shades. His every utterance was scrutinized for prophetic import. His status as generational oracle was earned by a triumvirate of hallucinatory folk-rock albums — 1965’s Bringing It All Back Home and Highway 61 Revisited and 1966’s Blonde On Blonde — that he would spend the rest of his career simultaneously trying to live up to and live down, never quite succeeding on either count.

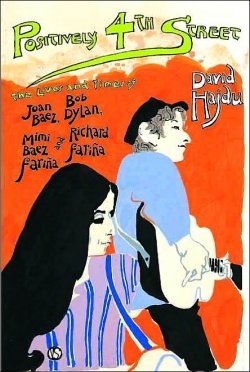

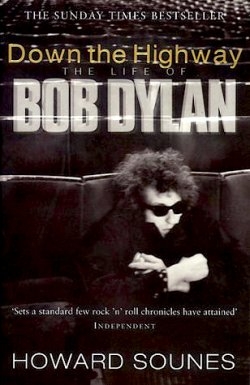

In the library of rock biography, Dylan has his own wing. Entire mountainsides have been deforested by countless authors attempting to decode the Mystery Tramp and the language he used — Amazon lists some 186 Dylan-related titles. Add to the pile Howard Sounes’ Down The Highway: The Life of Bob Dylan and David Hajdu’s Positively 4th Street. Sounes’ book is notable for its exhaustively researched dirt-digging — the boozing, the infidelity, the secret marriages, the bastard children. It is a detailed portrait of an artist becoming an old man, gracelessly weathering the indignity of outliving his own legend. But for all his fact-finding — searching court records, looking up deeds and land deals, tracking down cast aside mistresses and fired sidemen — Sounes never really discovers the Rosebud in Dylan’s attic. We learn all the mundane facts of Dylan’s amphetamine-fueled trajectory from Hibbing, Minn., to the center of the pop universe to the not-so-great beyond, but by the end of the book we don’t really understand the man any better.

On top of that, Sounes’ writing is at best passable and often embarrassingly inarticulate. Take for example this addled account of Rolling Stone critic Ralph Gleason showing Dylan around San Francisco: “Gleason met Bob and drove him around San Francisco, smoking pot during the tour. Suddenly it occurred to Gleason that he might have a wreck, while stoned, and kill the genius, and he quit using marijuana immediately.” Syntax police, arrest this man. Far more literate is Positively 4th Street, David Hajdu’s compelling account of the early ’60s folk boom as mirrored in the lives and times of Dylan, Joan Baez, her sister Mimi Baez and Mimi’s husband, author/Dylan wannabe Richard Fariña. Before he went electric, Dylan was the King of Folk and Baez was his queen.

According to Hajdu, Dylan ascended the throne on the back of Baez, who was already a national figure when she met the boyish, round-faced Woody Guthrie impersonator at Gerde’s Folk City in 1961. Richard Fariña — who would go on to write the proto-’60s novel Been Down so Long It Looks Like up to Me, still required reading for all aspiring college campus bohemians — reportedly told Dylan: “Man, what you need to do, man, is hook up with Joan Baez. She is so square, she isn’t in this century. She needs you to bring her into the 20th Century, and you need somebody like her to do your songs. She’s your ticket, man. All you need to do, man, is start screwing Joan Baez.”

According to Hajdu, Dylan ascended the throne on the back of Baez, who was already a national figure when she met the boyish, round-faced Woody Guthrie impersonator at Gerde’s Folk City in 1961. Richard Fariña — who would go on to write the proto-’60s novel Been Down so Long It Looks Like up to Me, still required reading for all aspiring college campus bohemians — reportedly told Dylan: “Man, what you need to do, man, is hook up with Joan Baez. She is so square, she isn’t in this century. She needs you to bring her into the 20th Century, and you need somebody like her to do your songs. She’s your ticket, man. All you need to do, man, is start screwing Joan Baez.”

Dylan would follow this advice literally and figuratively, glomming onto Baez’s audience and casting her aside when his own starpower began to outshine her as he morphed from topical folkie to electrified psychedelic riddler. In the spring of 1966, Fariña died in a motorcycle accident after celebrating the publication of Been Down so Long. A few months later Dylan, too, would crash his motorcycle. Although he survived the accident — and his legend would only grow larger during his lengthy self-imposed exile/rustic convalescence in Woodstock — something in Dylan died that day. He used to give a damn, but things had changed.

[This review first appeared in the June 13 2001 issue of Philadelphia Weekly]