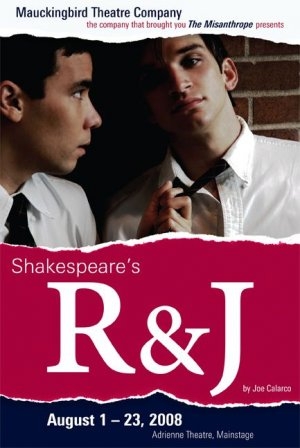

BY AARON STELLA As enjoyable as modern reproductions of Shakespeare’s “Romeo and Juliet” can be — especially those flush with glamorous nuances, such as Leonardo DiCaprio dueling in the streets of Verona with pistols instead of rapiers— these reproductions often evoke but a fleeting fondness. By comparison, Shakespeare’s R&J — which closed out an auspicious four-week run at the Adrienne Theater last night — is the stuff of true love, a remake unlike all the rest. Shakespeare’s R&J, prepared under the thespian expertise of Peter Reynolds, Director of the Mauckingbird Theater Company and of Temple University’s new musical theater program, is a radical revamp performed by a mere four actors cast as catholic school boys enduring the repressiveness of closed-minded society. At the same time, indirectly, the production, as per Joe Calarco’s adaptation, attempts to make sense of being gay in today’s world. I specify that the gay aspect conveyed “indirectly” because this variation of R&J isn’t your run-of-the-mill, in-your-face gay theater—hardly. “The first thing many reporters ask me is, ‘Is this political?’ or, ‘Is this about gay rights?’ and I just say ‘no’,” Reynolds says. “I am but a gay man…[who wants] universal themes to be present in the art that I make.”

BY AARON STELLA As enjoyable as modern reproductions of Shakespeare’s “Romeo and Juliet” can be — especially those flush with glamorous nuances, such as Leonardo DiCaprio dueling in the streets of Verona with pistols instead of rapiers— these reproductions often evoke but a fleeting fondness. By comparison, Shakespeare’s R&J — which closed out an auspicious four-week run at the Adrienne Theater last night — is the stuff of true love, a remake unlike all the rest. Shakespeare’s R&J, prepared under the thespian expertise of Peter Reynolds, Director of the Mauckingbird Theater Company and of Temple University’s new musical theater program, is a radical revamp performed by a mere four actors cast as catholic school boys enduring the repressiveness of closed-minded society. At the same time, indirectly, the production, as per Joe Calarco’s adaptation, attempts to make sense of being gay in today’s world. I specify that the gay aspect conveyed “indirectly” because this variation of R&J isn’t your run-of-the-mill, in-your-face gay theater—hardly. “The first thing many reporters ask me is, ‘Is this political?’ or, ‘Is this about gay rights?’ and I just say ‘no’,” Reynolds says. “I am but a gay man…[who wants] universal themes to be present in the art that I make.”

The script is practically identical to Shakespeare’s original, save a few abbreviated scenes substituted with some Shakespearean sonnets and stanzas from “A Mid-Summer Night’s Dream.” And the telling of the play itself is unique, specifically in its minimalism. Two boxes and a large chest are the only set pieces on the ground level stage, and the only significant prop utilized throughout the performance is a long silken-red strip of fabric. The actual telling of the play is done in the style one would expect tyrannized catholic high school boys would tell it: in lampoons and mockeries, sporadically sprinkled with bouts of horseplay; and in a highly unorthodox fashion, the players countenance intermittent laughter and sometimes momentarily step out of character, which engages the audience even more directly.

As for the characters themselves, the portrayal is all teenage variety : Romeo is impetuous, lustful, and a little cocky, while Juliet is bashful, goofy, and compulsively histrionic. Scene transitions are purposefully clumsy and noisily announced by the boys as they quickly rearrange the boxes. Whenever a looming patriarchal figure “enters” the scene, such as Lord Capulet or the Prince of Verona, two or more of the boys will join hands on the red cloth and begin firing off lines in a intimidating tenor to symbolize the oppressive tactics patriarchs have used to scare society into submission since god knows when. The one scene that stands out the most is the secret wedding of Romeo and Juliet. As Romeo and Juliet try to recite their vows, the other two boys try to cover Romeo and Juliet’s ears and try to pull the two lovers away from one another. A little violence eventually ensues, as the life on the stage fades to soft whimpers. At that point, the players discard their ties and blazers and untuck their shirts one by one — just as they are casting off the shackles of gender expectations and society’s pieties. All told, the play left a lasting impression and brought me to muse on its parts as I walked in silence that afternoon through Center City.