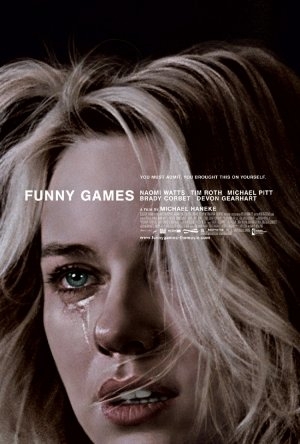

FUNNY GAMES (2007, directed by Michael Haneke, 107 minutes, U.S.)

FUNNY GAMES (2007, directed by Michael Haneke, 107 minutes, U.S.)

BY DAN BUSKIRK FILM CRITIC

“People have criticized me for making films just to provoke, That was never the case. But in this film yes. It made me happy to give an awakening kind of slap”. That’s Austrian director Michael Haneke being interviewed on the DVD of his breakthrough film, 1997’s Funny Games. Funny Games was a rigorous study of a viewer’s complicity with on-screen violence that invited the audience to watch helplessly (or not, which may be the film’s point) as a nondescript upper-class family are tortured to death in their home at the hands of two bratty young lads in sparkling white tennis gear. Since making that film a decade ago Haneke has become an art house fixture as a Cannes-approved scold of modern man’s failures. His last film, 2005’s Cache, merged his provocations with a more conventional thriller framework and moved his work into a potentially exciting nexus between an artful ambiguity and Hitchcock-style populism. Where would he go next?

The idea that his next film was an American remake of Funny Games was so perverse as to intrigue: what twist was he going to add? The surprising secret I’d never guessed was that he has absolutely nothing up his sleeve: the English language remake has arrived and apparently Haneke has no new reflections to add to his grim study in sadism. It nearly seems like a stunt meant to play one last mean trick on his audience, the cold leftovers of last night stomach-churning meal.

This “new” Funny Games is a just a few hairs shy of being a shot-by-shot, line-by-line re-creation of his 1997 version, as if none of the recent violent bobbings and weavings of the mass media have penetrated the skull of Mr. Haneke. We have the same slowly building passive-aggressive give and take, the same the sudden jolts of violence and the same endless shots of his camera staring blankly while characters struggle or lay dead in the corner. The two torturers still wear white and call each other Beavis and Butthead and the family still pleads and expires at all the same moments. It goes as far as to use the same music and it even has the same bold typeface in its credits.

Perhaps the strength of the basic premise will still work for viewers unfamiliar with the original, yet somehow it feels as forced as if you asked a lover to make love to you the exact same way they did last night. The meticulously-plotted film hits all the same notes but none of his new cast finds a way to breathe life to the characters on Haneke’s chessboard. The familiar faces of Naomi Watts and Tim Roth go through the same paces but their movie star histories (she was on Kong’s paw, fer chrissakes ) also brings a level of artifice to the story that undermines its wormy details from getting in one’s head. In the original, it was easy to place yourself in the shoes of its cast of unknowns; to see Naomi Watts in the same position presents the opportunity to ponder career moves and Oscar speeches.

To witness one of the current cinema’s most vigorous thinkers mucking around with his own predigested ideas is a sad sight, whether the decision to remake his own work is artistic wheel-spinning or a cynical business decision. Either way, Haneke’s film is either left superfluous for the director’s fans or out-of-step with modern events for those unfamiliar. I mean really, crossing the ocean to teach American’s about torture? Heck, we’ve spent the decade writing a whole new volume on the subject.