BY ELIZABETH FIEND LIVING EDITOR Not just one, but TWO different strains of fungi and a submarine are named after him. He was a man of great spirituality and faith, but subscribed to no specific church. He was recruited by Booker T. (though the MG’s weren’t around yet) and started out growing green onions. Aids to both Gandhi and Stalin asked for his advice. There are rumors that in an unimaginable act of racially-motivated violence he may have been castrated, and other rumors that his disinterest in female companionship simply implied that he was gay. Either way, he was doing it even before there was a word for it.

BY ELIZABETH FIEND LIVING EDITOR Not just one, but TWO different strains of fungi and a submarine are named after him. He was a man of great spirituality and faith, but subscribed to no specific church. He was recruited by Booker T. (though the MG’s weren’t around yet) and started out growing green onions. Aids to both Gandhi and Stalin asked for his advice. There are rumors that in an unimaginable act of racially-motivated violence he may have been castrated, and other rumors that his disinterest in female companionship simply implied that he was gay. Either way, he was doing it even before there was a word for it.

But he did not invent peanut butter.

That’s Dr. Booker T. Washington, the founder of Alabama’s Tuskegee Institute. The it is ‘chemurgy.’ And the man I speak of is George Washington Carver, whom I absolutely adore.

George Washington Carver knew the importance of the small family farm and of community service; he believed that we should look to nature for advice instead of trying to tame it to our will; he knew that eating healthy, nutritionally sound home cooking was vital to good health and that wastefulness is a bad thing.

that we should look to nature for advice instead of trying to tame it to our will; he knew that eating healthy, nutritionally sound home cooking was vital to good health and that wastefulness is a bad thing.

Although his contributions were born of economic necessity, his ideas are my ideals.

Here is a man whose work exemplifies so much of what we’re trying to get back to today. If he was alive he’d be a guru to the sustainable movement, the slow food movement, the holistic movement, the recycling, conservation and environmental movements. He understood the interconnectedness of things, and that ignoring this would have disastrous results.

He also would have brought something key that is missing in these movements: He would have brought poor people into the fray. Much of today’s progressive movements center around with the middle class and wealthy white people because, unfortunately, they’re the only ones who can afford the “luxuries” of healthy food, clean energy and organic cotton.

But Carver saw that the poor are the ones most affected by bad food options, high energy prices and lack of education. He believed that the poor would benefit most from a less wasteful world. He was a naturalist at heart and observed that nature did not waste anything, and he tried to do and teach the same.

George Washington Carver, a dynamic man, was born at one of the most dynamic times in American history, 1864 — the final year of the Civil War. Born a slave but emancipated by his first birthday, he struggled, as all blacks did, to find and define his place as a free man in an environment forced to change yet woefully unprepared for the challenge.

At first, things were going well but with the assassination of Abraham Lincoln coupled with the subsequent death of his Reconstruction Acts, and the rise again to power of the upper middle class white supremacist, this time called the Redeemers, what little gains given to the former slaves were lost and decades of unrest and attempts at acclimation into the mainstream followed. Even today.

But the world was a stimulating place for a man like Carver. He grew into adulthood at the same time exciting new fields and ideas were opening up at home and abroad. Darwin was doing his thing. Agriculture was just beginning to emerge as an actual scientific discipline. Mendel founded the science of genetics.

However, the future was not that bright for the poor, minorities and the uneducated. Two things happened at once. The plantations that had previously relied on the cheap source of slave labor now had to develop new ways to turn a profit. And, industrial capitalism was born. Along with these, social fragmentation.

America had seemed like a vast track of unspoiled, unlimited natural resources and natural splendor just a few years prior. But out west land was already turning to dust bowls and in the south, fields were depleted because of an over-reliance on cotton.

America had seemed like a vast track of unspoiled, unlimited natural resources and natural splendor just a few years prior. But out west land was already turning to dust bowls and in the south, fields were depleted because of an over-reliance on cotton.

While most agricultural researchers were headed towards industrialization of farming, Carver cared most for the people who were so low that industry didn’t even touch them. He devoted himself to the man farthest down.

In his work Carver concentrated on ways to help save the family farm, to preserve soil quality, to eat better, to discover more ways to reuse or recycle natural materials so less money had to be spent. He was into organics because fertilizers were too expensive for the poor to purchase. He developed farming methods that didn’t rely on heavy machinery.

In fact, he was exploring exactly what we’re coming to learn today is wrong with our agribusiness and farming methods; our attitudes towards wastefulness and careless abuse of the environment; our diet.

He floated the idea to use acorns — plentiful, free and a nuisance — as animal feed. He experimented with ways to make faux marble from green wood shavings and rope from cornstalk fibers. He developed paints, stains and color washes from clay and minerals in local soil and from native plants. All done with this in mind: cut down on costs, promote new local industry and small business, waste nothing.

And he taught people how to do all these things. Through his post at Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute he not only experimented and conducted classes but wrote and distributed newsletters. But he didn’t stop there. He also came up with the idea of a mobile education center which he called the Jessup Wagon, so that he could bring training straight to the farmers who needed it most.

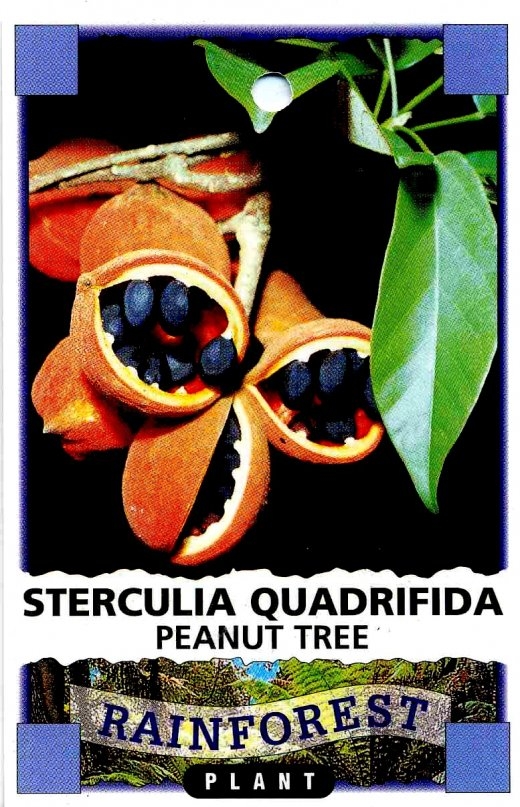

He urged crop rotation, switch out from tobacco and cotton to soil-healing, nitrogen-fixing plants like peanuts and sweet potatoes. Then he worked out ways that farmers could have added value from these new crops. By 1939 peanuts, which had never been grown much in the South, were a $200 million industry.

peanuts, which had never been grown much in the South, were a $200 million industry.

He developed recipes like sweet potato chips and wrote the pamphlet “How to Grow the Peanut and 105 Ways of Preparing it for Human Consumption.” He even led cooking classes to help and educate farmers’ wives.

He understood nutrition and the need for a balanced, varied diet. He devised ways to preserve food by drying it so people with meager means could obtain and maintain a hearty diet. He saw value in the homemade. He was into local plants, wild foods and the medicinal value of plants. He was into self sufficiency.

Carver called his work stovetop chemistry. It wasn’t until the 1930s that a real word was designated defining the division of applied chemistry that was concerned with cooking-up industrial uses from organic substances, chemurgy. Henry Ford just loved him for this and they would occasionally pal around.

During his life his fame, went up and down with the economy. During the world wars and the Depression his ideas were in vogue. Save, save, save. Reuse everything. Make something out of nothing. Here he was in his realm.

But when the economy was in an upswing, people doubted his contributions. Some even wondered if he was a scientist at all.

He was a smart guy, maybe a genius. But because of the color of his skin he had to struggle to educate himself; he had to sit at the back of the bus and had to stay in the servant’s quarters in fancy hotels even though he was the key-note speaker. He never received adequate funding or payment for his work. Today he’s trotted out in 5th grade classes as a great African American. But I think he should be regarded as an inspiration to us all and as a great man, period.

PEANUT COOKIES

by George Washington Carver

3 cups flour

1/2 cup butter

2 eggs

1 cup sweet milk

1 cup sugar

1 teaspoon baking powder

1 1/2 cups ground peanuts

Cream butter and sugar; add eggs well beaten; now add the milk and flour; flavor to taste with vanilla; and the peanuts last; drop one spoonful to the cookie in well greased pans; bake quickly.

On George Washington Carver’s tombstone: “He could have added fortune to fame, but caring for neither, he found happiness and honor in being helpful to the world.”

Sources and For More Information:

About George Washington Carver:

http://inventors.about.com/library/weekly/aa041897.htm

http://lib.iastate.edu:9060/gwc/bio.html

http://www.ideafinder.com/history/inventors/carver.htm

http://www.suntimes.com/food/765230,013108carver.stng#

George Washington Carver, Scientist and Symbol by Linda O. McMurry [book]

You can see more of George Washington Carver’s recipes in this 2005 cookbook The African-American Heritage Cookbook: Traditional Recipes and Fond Remembrances From Alabama’s Renowned Tuskegee Institute by Carolyn Quick Tillery.

About Tuskegee University:

http://www.tuskegee.edu/Global/category.asp?C=34069&nav=menu200_1

About the Civil War:

http://us.history.wisc.edu/hist102/weblect/lec02/02_preamble.htm

ABOUT THIS COLUMN: At no time in recorded history have we possessed so much knowledge about health and nutrition, or had such vast and effective means for disseminating that knowledge. Yet for all that, we essentially live in a high-tech Dark Age, with most of the global population ignorant or confused about the basic facts of their own biology. How did this happen? Well, that alone is a whole six-part miniseries, and this ain’t the Discovery Channel. Suffice to say that the bottom line of many a multi-national corporation depends on that ignorance, and vast sums of money are expended to keep us fat, dumb and happy. But mostly fat. There was a time when newspapers saw it as their duty to truth squad the debates over health, science and the environment, but that’s a luxury most papers can no longer afford — not when there are gossip columnists to be hired! To help remedy this violation of the public’s right to know, Phawker publishes the JUNK SCIENCE column by Elizabeth Fiend, beloved host of the BiG TeA PaRtY. Every week, Miss Fiend connects the dots to reveal a constellation of scientific facts that have been hiding in plain sight, scattered across the cold, vast reaches of the Internet. With a background in punk rock and underground comics, and a long career as a library researcher, Miss Fiend doesn’t pretend to be a scientist or an expert. She does, however, know how scientific facts become diluted by corporate-sponsored non-facts, and every week she separates the smoke from the mirrors. Why? Because she loves you.