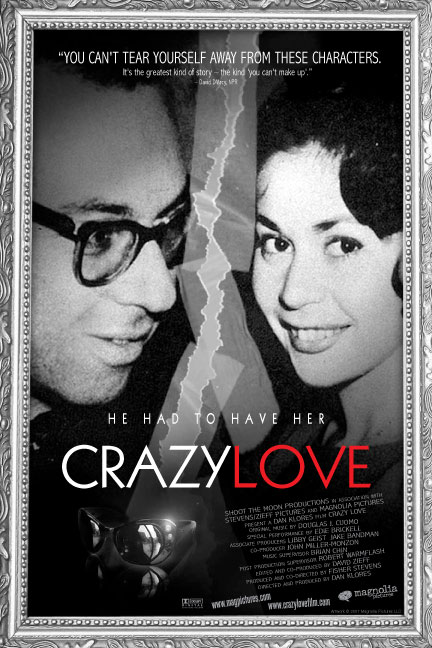

CRAZY LOVE (2007, directed by Dan Klores & Fisher Stevens, 92 minutes, U.S.)

CRAZY LOVE (2007, directed by Dan Klores & Fisher Stevens, 92 minutes, U.S.)

BRAND UPON THE BRAIN! (2006, directed by Guy Maddin, 95 minutes, U.S./Canada)

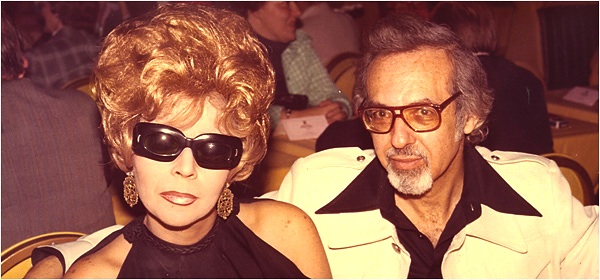

When it comes to telling a melodramatic story through weathered old imagery, few recent films have done it better the new documentary Crazy Love. Rescuing a 50-year-old tale from ancient tabloids, this expensively-mounted doc tells the tumultuous saga of Burt and Linda, a Bronx couple whose romance crashed to a halt in 1957 when the jealous Burt hired men to throw lye into her face, after she dumped him to accept an engagement to another man. Crazy Love interviews each of them separately, hiding until well into the film the the fact after 14 years of incarceration, Burt left prison and won Linda back. This is unimaginably magnanimous of Linda, considering she had been left blind and bald from the attack.

It’s a masterfully mounted documentary which has received only guarded praise from critics, who seemingly want to restrain their acclaim for a film whose details could fit nicely into a bad A&E true crime show. Like Capturing the Friedmans, Tarnation or last year’s The Devil and Daniel Johnston, Crazy Love achieves a startling intimacy with its unlikely lovers, whose twisted narrative takes on the air of myth by benefit of the enduring mystique of 1950s New York City. Burt was a lawyer, rich from his questionable practice, and lived a lifestyle that seemed modeled on Hugh Hefner’s Playboy philosophy. He produced B-movies, drove a powder blue Caddy and owned a nightclub, the clubhouse which the nerdy and bespeckled Burt used to seduce women. Through stock footage, home movies and some stunning amateur photography co-directors Dan Klores (yes, the agent) and Fisher Stevens (yes, the actor and Hollywood Squares regular) re-animate this lost world with the spark of a lost sub-plot from Goodfellas.

Hollywood Squares regular) re-animate this lost world with the spark of a lost sub-plot from Goodfellas.

A collection of fascinatingly grizzled women and men from the couple’s inner circle aren’t too shy to talk about the mixture of loneliness, vulnerability and nostalgia for that lost New York moment that would make Linda return to the pathologically dishonest Burt. After gazing into those half-century old photos of the striking young Linda’s baby blues, we never see her again without her dark Jackie O. sunglasses; we may not be able to look into her eyes but Crazy Love shows real insight by taking seemingly mad acts and letting us see them as comprehensible.

In 1988, as the midnight movie craze was grinding to a halt, I went to see Guy Maddin’s debut feature Tales from the Gimli Hospital in Philly’s tiny Roxy Theater. Looking like a decaying film of the 1920s or ’30s, Gimli told a tale of plagues, retribution and fish oil in a transparently fake antique style that was like nothing I had ever seen before.

Nearly two decades later, I can now say I’ve seen many films like Gimli, although they’re sprung from the same place, the mind of the early cinema-obsessed Canadian Maddin. With his eighth feature, Brand Upon the Brain, Maddin’s critical cache may be larger than ever, but as someone who has been on this ride since the beginning, Maddin’s kit box of repressed emotion, German expressionism and scratchy film stock is starting to seem as predictable as the type font to be used in the credits of Woody Allen’s next film (that’s “Windsor-EF Elongated”, as most type freaks know).

For those unfamiliar with Maddin’s work, the synopsis may sound insane. But trust me, this is business as usual for the single-minded Maddin. A character named Guy Maddin (played not by the director but an actor named Erik Steffan Maahs) returns to the lighthouse in which he was raised with his overbearing mother, workaholic scientist dad and similarly lonely and pining sister. He flashes back to his youth, where his family runs a very strict orphanage.  When the children begin appearing with carefully drilled holes in their heads, a harp-playing teen detective named Wendy Hale pops up to investigate. Changing clothes so she can pass herself off as her twin brother, Wendy toys with the hearts of Guy and her sister while investigating Guy’s increasingly suspicious parents.

When the children begin appearing with carefully drilled holes in their heads, a harp-playing teen detective named Wendy Hale pops up to investigate. Changing clothes so she can pass herself off as her twin brother, Wendy toys with the hearts of Guy and her sister while investigating Guy’s increasingly suspicious parents.

Making all this silliness palatable is Maddin’s trademark style, where the story unfolds through a blur of inter-titles, montages and print damage, and the acting is straight from the silent school of large dramatic gestures. This bold conception has made Maddin one of the few experimental filmmakers to regularly receive distribution in the U.S., but has anyone noticed how little experimentation he has done in recent years? A decade ago, Maddin had a famously troubled production called Twilight of the Ice Nymphs, a film of firsts for his work: A name cast, shot in color and with a somewhat more conventional script. It received almost no distribution in the U.S. and Maddin’s career seemed to be sunk until 2000 when his brilliant short The Heart of the World found unlikely success and re-energized interest in his work.

Since then, Maddin has delivered exactly the scratchy tics and quirks audiences have expected of his films. Nobody goes to a Maddin film expecting the unexpected — that’s one way of looking at it, anyway. That his ideas have calcified into stasis and repetition is another.