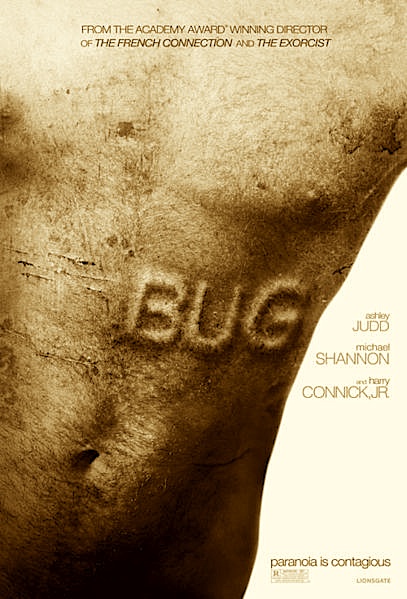

BUG (2006, directed by William Friedkin, 102 minutes, U.S.)

BUG (2006, directed by William Friedkin, 102 minutes, U.S.)

BY DAN BUSKIRK FILM CRITIC

With monster sequels from blockbuster franchises gobbling up the majority of megaplex screens at the kick-off of the summer season, Lionsgate is doing some crazy counter-programming by attempting to pass off William Friedkin’s adaption of the Tracy Lett’s stage hit Bug as a Saw-like horror film for the blood-drunk masses. While this slow-building, claustrophobic psychological thriller ultimately ascends to a climax as gruesomely horrific as Requiem For A Dream’s, Bug would have likely found a more accepting audience in the art-house circuit rather than being booked across the hall from Gothic horrors like Disturbia. Even with Ashley Judd trading in on her success in a number of “Babe in Danger” crime films, the Riverview’s crowd wasn’t buying it; I heard two different audiences loudly moan at the script’s Sam Shepard-style angst, and they didn’t seem like they would appreciate anything wimpier than a slow-motion scene of a drawing-and-quartering. I tell ya, these American movie audiences are getting tougher every year.

Judd doesn’t hide the lines on her face as Agnes, a woman whose life consists of serving drinks, freebasing in her motel room residence and dreading the return of her abusive ex-husband Jerry (Harry Connick Jr.) from the house of corrections. A friend of Agnes’ brings a welcome distraction by to party one night, the polite but insular Peter, whose guarded manner hides a slowly unraveling psyche. Set almost entirely in an isolated Oklahoma motel (the camera helicopters across the early evening nothingness in the opening shot, finally descending on this little spot of Hell), Bug brings these two lovers together under a palpable atmosphere of unease as what begins as an annoying chirping cricket multiplies until our tweeking couple are itching and scratching at an invisible infestation of aphids crawling all over their bleeding bodies.

When Michael Shannon originated the role on the New York stage, the New York Times reviewer Ben Brantley had deep praise for the performance, stating “I’ve seldom seen a young actor turn up the volume of a performance so slowly and skillfully.” Peter’s transformation from cautious and straight-spoken Gulf War vet to fire-spouting preacher of conspiracy theology is the sort of meaty role that invites no-holds-barred scenery chewing. Shannon carefully modulates Pete’s evolution into unrestrained batshit craziness so that the performance that never loses its credibility, always maintaining a strained sympathy as he desperately tries to convince Agnes of delusions he knows are true. Judd has spent most her career being better than the material she’s given, and the challenge of meeting Shannon’s virtuoso performance inspires some of the best work of her career.

The direction is razor-sharp and unsentimental, and if you had to guess you’d say its the work of a hungry and promising new talent on the scene, but no; it’s the handiwork of 1970s bad boy genius William Friedkin. With The Exorcist and The French Connection to his name, Friedkin has directed two of the seminal works of American film and enjoyed the same respect guys like Coppola did in the 70s. While Friedkin has directed mostly pedestrian crap since his flashy and nihilistic 1985 crime drama To Live and Die In L.A., even with junk he still regularly shows flashes of kinetic brilliance. Shot independently for a reported $4 million, people have been hailing Bug as a triumphant return to lean and mean genius for the 71-year-old director. It is his best film in years, yet despite the film’s effectiveness it all seems a bit slight for a director of Friedkin’s experience and stature. Maybe Bug’s downbeat aura has sunk into my soul but I find my joy at Friedkin’s changing fortunes tempered by the fact that the industry hasn’t found a more fitting assignment for a talent as undeniable as the still potent whirlwind they once called Hurricane Billy.