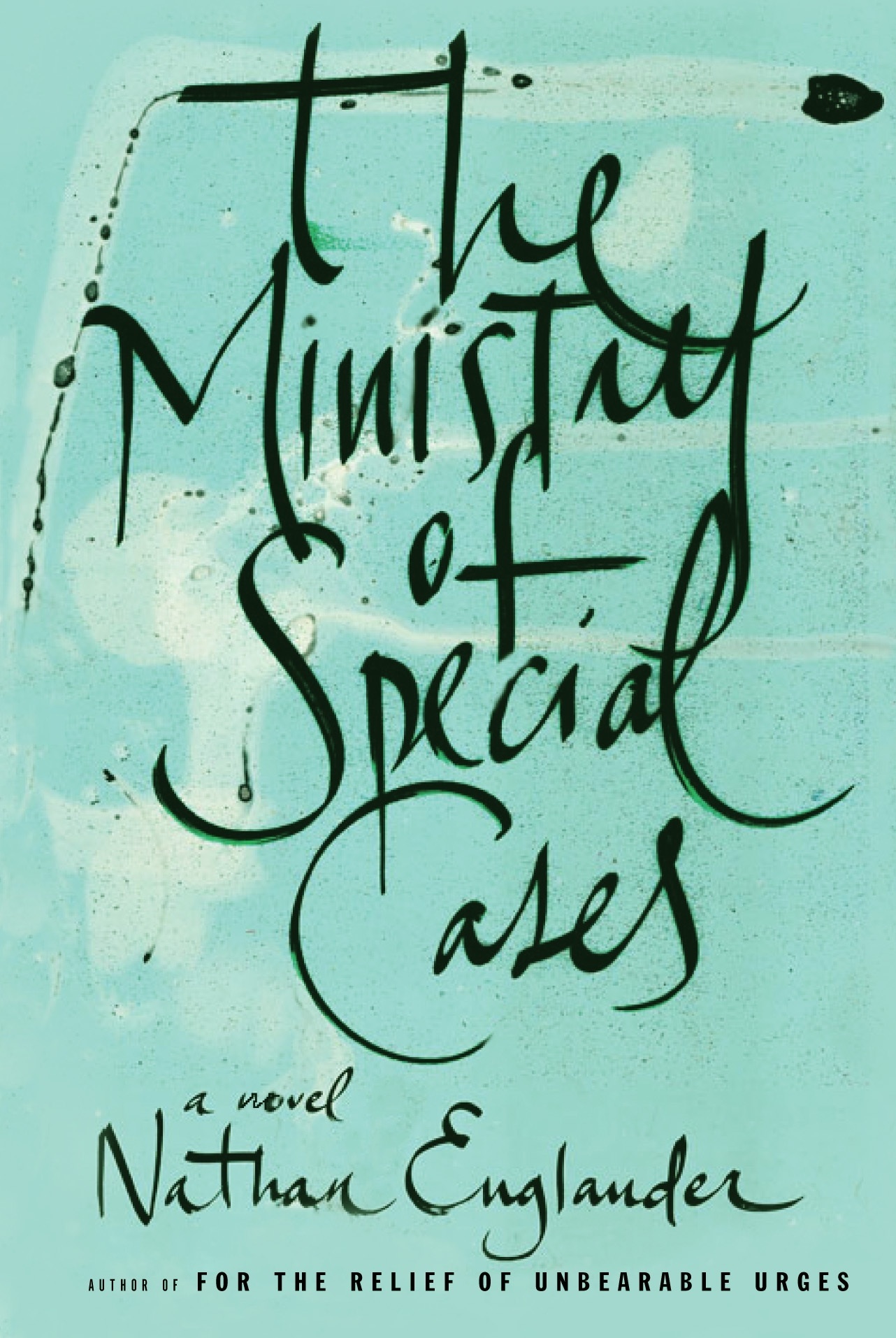

BY MAVIS LINNEMANN BOOK CRITIC Eight years after the critically-acclaimed short story collection The Relief of Unbearable Urges, Nathan Englander’s first novel, The Ministry of Special Cases, finally hit bookstores on May 1. This harrowing novel takes place during Argentina’s Dirty War (1976-1983), during which the junta government “disappeared” somewhere between 9,000 and 30,000 suspected dissidents and subversives, mostly students and liberals. Kaddish Poznan, hijo de puta (son of a whore) and outcast in the Jewish community, makes his living by erasing the names of wanton Jewish ancestors (pimps, whores and gangsters) from their gravestones on requests from more respectable family members who want to disassociate themselves from their licentious dead. His son, Pato, wants nothing to do with the family business, but Kaddish insists on keeping him involved. Kaddish’s wife, Lillian, works a stable job at an insurance company. Things start going bad when Kaddish accepts two nose jobs in exchange for cash, and manages to chop off part of Pato’s finger during a late-night name removal. When Pato is “disappeared,” Lillian and Kaddish embark on the daunting task of retrieving their son, each through their own means. Kaddish takes the seedy, underground path, while Lillian chooses to make daily visits to the absurd, Orwellian labyrinth of the Ministry of Special Cases. What ensues is a heart-wrenching story about fathers and sons, memory and loss, shame and heritage, and most of all, hope and hopelessness.

BY MAVIS LINNEMANN BOOK CRITIC Eight years after the critically-acclaimed short story collection The Relief of Unbearable Urges, Nathan Englander’s first novel, The Ministry of Special Cases, finally hit bookstores on May 1. This harrowing novel takes place during Argentina’s Dirty War (1976-1983), during which the junta government “disappeared” somewhere between 9,000 and 30,000 suspected dissidents and subversives, mostly students and liberals. Kaddish Poznan, hijo de puta (son of a whore) and outcast in the Jewish community, makes his living by erasing the names of wanton Jewish ancestors (pimps, whores and gangsters) from their gravestones on requests from more respectable family members who want to disassociate themselves from their licentious dead. His son, Pato, wants nothing to do with the family business, but Kaddish insists on keeping him involved. Kaddish’s wife, Lillian, works a stable job at an insurance company. Things start going bad when Kaddish accepts two nose jobs in exchange for cash, and manages to chop off part of Pato’s finger during a late-night name removal. When Pato is “disappeared,” Lillian and Kaddish embark on the daunting task of retrieving their son, each through their own means. Kaddish takes the seedy, underground path, while Lillian chooses to make daily visits to the absurd, Orwellian labyrinth of the Ministry of Special Cases. What ensues is a heart-wrenching story about fathers and sons, memory and loss, shame and heritage, and most of all, hope and hopelessness.

***

***

Phawker: Why did you decide to set the novel in Argentina during the Dirty War?

NE: It’s very strange to communicate this to you. It’s weird the things that are just so internal. It’s sort of like asking me, “How does your head work?” in that sense, there’s just endless themes that I was interested in, whether it was community, or just identity, or the time and space continuum, how things link through space, names, religion, all these things, and then injustice, and governments gone awry, and the life of the individual in an urban center, and again, a really overriding obsession with bones and burial.

I was living in Jerusalem at the time and I guess, I’d had these Argentine friends from back in the ’80s and I saw these guys really shaped by politics. I guess as all this stuff just comes together for me, and I’d been to Argentina in 1991. When the ideas of this novel started to grow, it was just really clear to me that Argentina was the perfect place on which to set this story. I like a pressurized novel. I like a pressurized story. And it’s just such a complicated place and it was such a terrible, dark time. I feel like, and again, even though they maybe were dark ideas, I felt like that was the place where they would flower, in this setting. In many ways, you write a book in the world. So in many ways, living in Jerusalem started to affect how I saw things and it became a Jerusalem metaphor in a way, and it’s very strange for me. I was writing about a metaphor in the book — habeas corpus — and what was later a metaphor ended up with a political position in America only due to the insanity of the current state of affairs. In that way, it’s interesting to me that people keep referring to this as a political book; it sort of ended up being more political. The point is how do those things feed into my head. I change as I’m writing this, and the book changes. I’m so thankful that I chose that as the place. I became obsessed with that time and that place . . . If I didn’t bump into these Argentine guys, if I hadn’t made these friends, I might not have ever heard of these, and that’s kind of shocking to me now.

many ways, you write a book in the world. So in many ways, living in Jerusalem started to affect how I saw things and it became a Jerusalem metaphor in a way, and it’s very strange for me. I was writing about a metaphor in the book — habeas corpus — and what was later a metaphor ended up with a political position in America only due to the insanity of the current state of affairs. In that way, it’s interesting to me that people keep referring to this as a political book; it sort of ended up being more political. The point is how do those things feed into my head. I change as I’m writing this, and the book changes. I’m so thankful that I chose that as the place. I became obsessed with that time and that place . . . If I didn’t bump into these Argentine guys, if I hadn’t made these friends, I might not have ever heard of these, and that’s kind of shocking to me now.

Phawker: How much of this novel is taken from actual events that took place during the Dirty War?

NE: Everything that would seem made up is true, and everything that would seem true is made up. People say to me, “Well they didn’t really grab innocent college students off the street and drug them and torture them and strip them naked and then drop them alive from helicopters, or drop them from C1-40 planes into the river. Of course, you made that part up.” No, that’s the historical record . . . I feel like the craziest parts of the novel I had to tone down because they were true, but that doesn’t matter. You have to make them fit into that world. It’s just too insane what happened.

Phawker: When did you decide to switch from writing short stories to writing novels?

Nathan Englander: It was always something I wanted to do, basically. People always wonder, “Oh did the publisher make you [switch]” There’s this idea that everybody likes to beat up on the short story. I absolutely love the short story form. As I reader I love it, and I really believe in it, again as form. But after that I really did want to try and find my way around the novel. I kind of compare it, as if you had a successful gallery of show of paintings and then became an industrial sculptor. It’s just an absolutely new form. I always wanted to tackle it. It was a full-on education and now I really love novels, as well. It was a completely different experience. My head is brimming for both; I can’t wait to write stories again. I’ve got the next novel lined up too.

Phawker: So you’re going to write another novel?

NE: Who knows? I’m very thankful that I get time to write, because that’s what most writers are after. I’m never not thankful for it. So, it’s this book launch time where you’re pulled away from your desk, where it’s nice to have that yearning again, where I’m just dying for the time to sit down and write this one story or to dig into the next book. I don’t know which way my head will go, but it’s kind of brimming right now. It’s a fun time when everything is in a raw-idea form.

Phawker: Did you have to change your mindset in order to write the novel?

NE: No, everything in the world is confusing to me; it’s just odd that craft is very clear. It’s just finding a rule, like building an asthetic and understanding how the world of the novel works. So, maybe it is changing a mindset — but it’s more seeing what novel needs that is different from the stories.

Phawker: What’s that?

NE: It’s a sense of gravity, the balance of things. I feel like a story itself can carry a short story through. There are perfect stories that exist in the world that are wholly story-based and that’s enough to carry it. I feel like in a novel, the character plays a different role. It’s the character that carries the novel through, even if it’s plot-driven. I really feel like it’s of the character in a very different way, having that time to stay with someone — I really see it in terms of weights and measures, like shifting senses of gravity, and that was a big lesson for me. When you build a short story, you build a whole complete world, finish it and then start the next one. It’s rebuilding that whole universe again, which is why I find them so amazing. What they should be, these perfect little worlds, but each time building it from nothing. It’s very strange to remember. I guess I haven’t thought about this in a long time, but it’s like getting to a new chapter in the novel, and being like, “You mean I get to keep this guy? I don’t have to rebuild the living room again? I don’t have to move the couch?” It was sort of shocking. It made its own demands that took me a decade. Everything is overwhelming to me; it takes me a long time and demands endless attention from me, that’s how I am.

Phawker: I read somewhere that the manuscript was actually really humongous?

NE: Well, I don’t believe in block. I don’t believe in stage fright or in writer’s block, because it’s just too crippling. So I skipped those two things, everything else I’m afraid of. I just fill endless, endless pages. I wrote a year and threw that out. And then I wrote another year and threw that out too. I handed in to my agent around 600 pages — with all the footnotes and stuff, it had to weigh in almost a 1000 pages. I’m just crazy. There’s just annotations on the annotations.

Phawker: What have you been doing for the past eight years, besides writing The Ministry of Special Cases?

NE: Well, I’m a big coffeehouse writer, otherwise I’d go mad. I’m a social being who has an isolating job so I like the white noise. I like the people being around. I’m also good at hobbies; whatever I touch ends up being an obsession. I was like, writing? Oh, I need to be a writer, that’s it. But when I picked up a camera, I ending up losing a year, a great year. But I was suddenly managing a studio in Chelsea and working as a professional. I start running a little and then suddenly I’m running distance. I became obsessed with running and then switched that to yoga, but now I mix them up.

Phawker: The main character in this book, Kaddish, is an outsider in the Jewish community. Did any of your own experiences influence this character?

NE: The first book, the stories for me were really about being on the outside. The first book was really about the balance, the secular and the religious and finding this place between two worlds. As I got older and I was really about living in Jerusalem and finding my own place, do I identify as Jewish or American? Like feeling Jewish in America and then getting to Israel and feeling American. The outsider thing; I just became fascinated with the idea of community and the role of the outsider within it. I almost think, the longer you identify, this book I’ve been writing for a long time now, basically since I was 24, 13 years already where I live a writer’s life. You start to recognize your role on the inside and the outside.

I also got obsessed with this idea, the way in communities everyone loves to claim this person is embarrassing us or this person is the outsider, that role Kaddish plays and I wanted to explore this idea that a community actually needs its pariahs . . . it’s the people on the outside within the community that the community needs to see itself. And that’s the idea I got really interested in with Kaddish. This idea where he’s on the outside, and they kept him on the outside, and this terrible shame. Almost like if you said, would they be better off without him? No, they wouldn’t exist without him. Communities need these people to say, “That’s our line and you’ve crossed it. We’re going to punish you.” I feel like communities really relish around this structure . . .I really got interested in these ideas of what a community owes its members and where these lines are. I feel like loyalty should be a very deep thing, almost unbreachable, if you’re truly loyal.

Phawker: Both Kaddish’s work in the cemetery and his rhinoplasty bring up the idea of erasing “shameful” heritage and history. Did you find this theme came up a lot when you were doing research?

NE: I discovered that theme living inside my head. It’s a Jewish guilt thing, and a shame thing. My whole life is just guilt and shame; it’s exploration of that and where that comes from, and why that’s so big for me, this apology for existing, in a sense, that can permeate everything.

Phawker: Why did you decide to focus so much on nose jobs?

NE: Argentina is a country that is obsessed with plastic surgery. [They] might even outdo us in America here. I just got more interested in this idea in all these ways, back to linking through time and identity and what we are bequeathed and who we become. Plastic surgery is a physical way to break those links. As much as this book is [about] how we identify ourselves, as much as we are tied to the name, aren’t we even more tied to our faces? . . . The idea [of] what you’re trying to change on the inside when you change the outside, and if its changeable. If a mother and father both change their faces and have a baby, the kid’s going to look like these people that they’ve chosen to erase — their own selves. It’s interesting to look in the mirror and have to ask your parents, why don’t I look like you? Because we decided that those looks needed to be altered, but you’re cute.

Phawker: My parents are actually funeral directors, so I thought the whole theme of bones and burials was really interesting.

NE: You know that’s funny; I never would have remembered this. The year that I was managing that photography studio . . .this guy, he was an art director, he was older and I guess he was a hippie, and his parents were funeral directors and they owned a graveyard . . . he told me he was digging a grave while tripping and the dirt was coming down in clouds around him. And that went into my head and who knows? That’s point number 764 towards how this became a book.

Phawker: There’s a lot of focus on building the future by erasing the past. Why this theme, do you think this is something we’re doing in America now?

NE: I can’t believe that I ended up with a political novel on accident. So many of the reviews that have hit so far have not let up on that . . . I’m very shy about giving positions until I feel more versed. . . . What exactly are writers expert in? Nothing. . . . I was telling this story. The fact now that the story that I told actually ended up echoing [current events]. I was using my habeas corpus metaphor, then actually America chose, during my writing about this, to suspend habeas corpus. I sort of inherited a very obvious political position that I don’t know what to do with. It’s a very silly political position. Here’s my fierce political position: I think in a democracy, if someone is arrested by the government they should be entered into the legal system. It’s crazy. It’s 1,000 years old. . . . It was always my worst nightmare, to be wrongly accused. You really want to know that if you’re arrested and haven’t done anything that you will be able to talk to someone. It’s really just basic human rights. I was telling this story and exploring this world. If anything, it was this Dirty War story, whether in the community element, to explore the idea of identity, but also this idea of what it is, the idea of the disappeared but through this one family. It was not actively political in that way.

Phawker: Will you move back to Jerusalem anytime soon?

NE: No, I went back in May [2006] . . . [but] I’m not going anywhere. I’m turning into Woody Allen. Just the idea of touring. The idea of Brooklyn gives me a nosebleed. Just the idea of having to go on tour is shocking to me [right now].

Phawker: Anything in the works?

NE: Me? Dr. Speedy? Speedy McWriter? I know the next book, and I know the stories. I owe someone a play that I’m really excited about. There’s all kinds of stuff to do. Yes, I have endless, endless tons in the works and I can’t wait to work on it, but I’m also very excited after all these eight long years to go out and meet readers. Just seeing the books in stacks is shocking to me, considering I’ve carried around the only copy on my back for so long.

[Photo by ELENA SEIBERT]