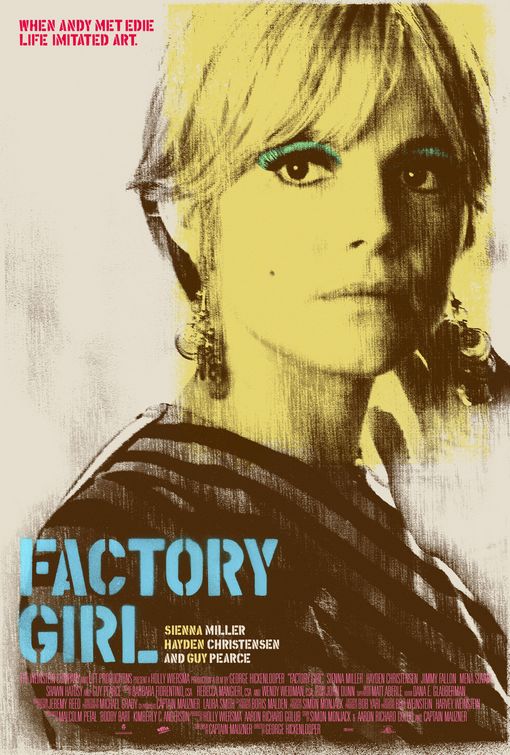

(2007, dir. by George Hickenlooper 90 minutes, U.S.)

(2007, dir. by George Hickenlooper 90 minutes, U.S.)

BY DAN BUSKIRK FILM CRITIC When you’re sent to review a film, you must have the patience of a priest and the endurance of a superhero, and refuse to pass judgment until the final credits finish rolling, no matter how badly your Spidey senses are tingling. Sad to say, it only took a few minutes of Factory Girl to sorely test my priestly patience. Director George Hickenlooper’s game plan — take this radical culture star and shoe-horn her life into the staid biopic formula — was apparent right out of the gate. By the time Warhol arrives, like a wacky sitcom neighbor, my heart knew that Factory Girl was going to drain any mojo that might be left in the legend of the tragic 60s icon. Still, I’m nothing if not a pious believer, and my faith returned once I gave up any ideas about the importance of “quality” and relaxed, enjoying how much fun a badly mounted drama set in Warhol’s Factory could still be.

To enjoy Factory Girl, it’s best to ignore Sierra Miller as Edie Sedgwick. Miller may be giving it her all as the old- money debutante turned Warhol Superstar, but when she reaches for the script, co-written by Captain Mauser (who did that awful John Holmes flick a few years back), it’s an anvil, not a life preserver. Hickenlooper is happy to have her lounge around naked and bemoan her past, but he never successfully breathes life into the legend. Truth is, I’m not sure there was much more to Edie than Hickenlooper fills in, but what separates her from, say, Anna Nicole Smith is the kind of company she kept.

In a word: Warhol.

David Bowie made him a regal nebbish in Basquiat, Crispin Glover made him a insecure pile of goo in The Doors and I suspect it is the power of Warhol’s genius itself that makes it hard for an actor not to be entertaining playing the Prince of Pop Art. Guy Pearce takes a crack at it here and he’s the liveliest thing in Factory Girl, full of youthful energy as he chomps his gum and woos Edie with a pick-up line he borrows from his elderly Slavic mother, “You’re the Boss, Applesauce”.

But Andy’s the only Boss in this Factory, and once Edie falls for another icon (an unnamed character listed in the credits as “Musician” but CLEARY intended to be Bob Dylan) Andy turns into a vindictive vampire queen, another cruel Daddy figure heartlessly driving our wispy waif to an early grave.

About that “Musician”: Once Bob Dylan threatened to sue over their wildly conjecture-driven script, the film erased all mention of the singer’s name. This is the first film I can remember to cast an actor as Dylan and who better for the task than Hayden Christensen, so famously bad as the future Darth Vader in the second Star Wars Trilogy. Christensen’s dead eyes suggest a hollow center where emotions are supposed to reside; he couldn’t summon the blackheartedness of the Lord Vader, nor can he exhibit the wit and heavy-osity of a young Dylan, turning him into some hectoring old prig too uptight to enjoy the silver-lined good times at the Factory.

The idea of pitting Dylan’s old world wisdom against Warhol’s commercial deification in a battle for Edie’s soul is a titillating one, but Hickenlooper can’t make much out of it as he continues directing the overly-literal script as if it was a Lifetime TV movie.

While Factory Girl suffers from a lack of success on nearly all artistic fronts, oddly, this doesn’t stop it from remaining stupidly entertaining throughout. Hickenlooper?s camera never lingers, but the scenes that flash by continually amuse in their attempt to boil down these complex artists into a few simple gestures. Look! There’s Andy on the set of his film giving some passerby the camera! Hey! Isn’t that Weezer droning along as the Velvet Underground?! There’s Dylan dressed as a sheepherder, wearing shades and driving his cycle! Keep your eyes on the road and your hands upon the wheel, Mr. Dylan!

It reminded me more than a little of that fictionalized biopic of Carole King from 1996, Grace of My Heart. Grace played even looser with the facts, having the Carole King character marrying Matt Dillon playing a suicidal fake Brian Wilson. That movie stunk to high heaven too, but there is such potent residual power in these 20th century icons you can’t help worshiping them a little even if — and just possibly because –their lives are rendered as velvet paintings.