EDITOR’S NOTE: This interview originally posted on November 17th 2011, upon the publication of Adam Gopnik’s book The Table Comes First: Family, France & The Meaning Of Food.

BY JONATHAN VALANIA Longtime New Yorker staff writer, author, essayist, children’s novelist and Philly homeboy Adam Gopnik will be delivering the keynote lecture of the Philadelphia Museum Of Art’s Object Lessons: New Thinking about Still Life symposium at 6:30 pm tonight — his talk is called Things that Mean Things: Objects and Inventory in American Art. Back in 2011, we got Gopnik on the horn and we discussed writing, food, crime and punishment, the necessity of factory farming, the slow dissolve of print into the digital ether, the uncertain future of the New Yorker, the secret world of children’s literature, the enduring power of Tolkien, seeing Hendrix and the Incredible String Band at the Electric Factory, doing avant garde theater on South Street in the late 60s and why the HoJos on City Line Avenue will forever hold a sacred place in his heart of hearts.

BY JONATHAN VALANIA Longtime New Yorker staff writer, author, essayist, children’s novelist and Philly homeboy Adam Gopnik will be delivering the keynote lecture of the Philadelphia Museum Of Art’s Object Lessons: New Thinking about Still Life symposium at 6:30 pm tonight — his talk is called Things that Mean Things: Objects and Inventory in American Art. Back in 2011, we got Gopnik on the horn and we discussed writing, food, crime and punishment, the necessity of factory farming, the slow dissolve of print into the digital ether, the uncertain future of the New Yorker, the secret world of children’s literature, the enduring power of Tolkien, seeing Hendrix and the Incredible String Band at the Electric Factory, doing avant garde theater on South Street in the late 60s and why the HoJos on City Line Avenue will forever hold a sacred place in his heart of hearts.

PHAWKER: You grew up in Philadelphia. How long did you live here?

ADAM GOPNIK: I was born in the Lankenau Hospital and I lived in Philadelphia until I was 12, went to the H.C. Lea school on 47th and Locust, I think it’s still there. I lived on 41st and Locust until my parents – my parents were graduate students at Penn, my dad taught at Rutgers, then they both got jobs at McGill, then we moved to Montreal.

PHAWKER: Any distinctive memories from that time?

ADAM GOPNIK: Oh my God, my whole childhood is there, I don’t know where to begin.

PHAWKER: Generally positive or generally negative?

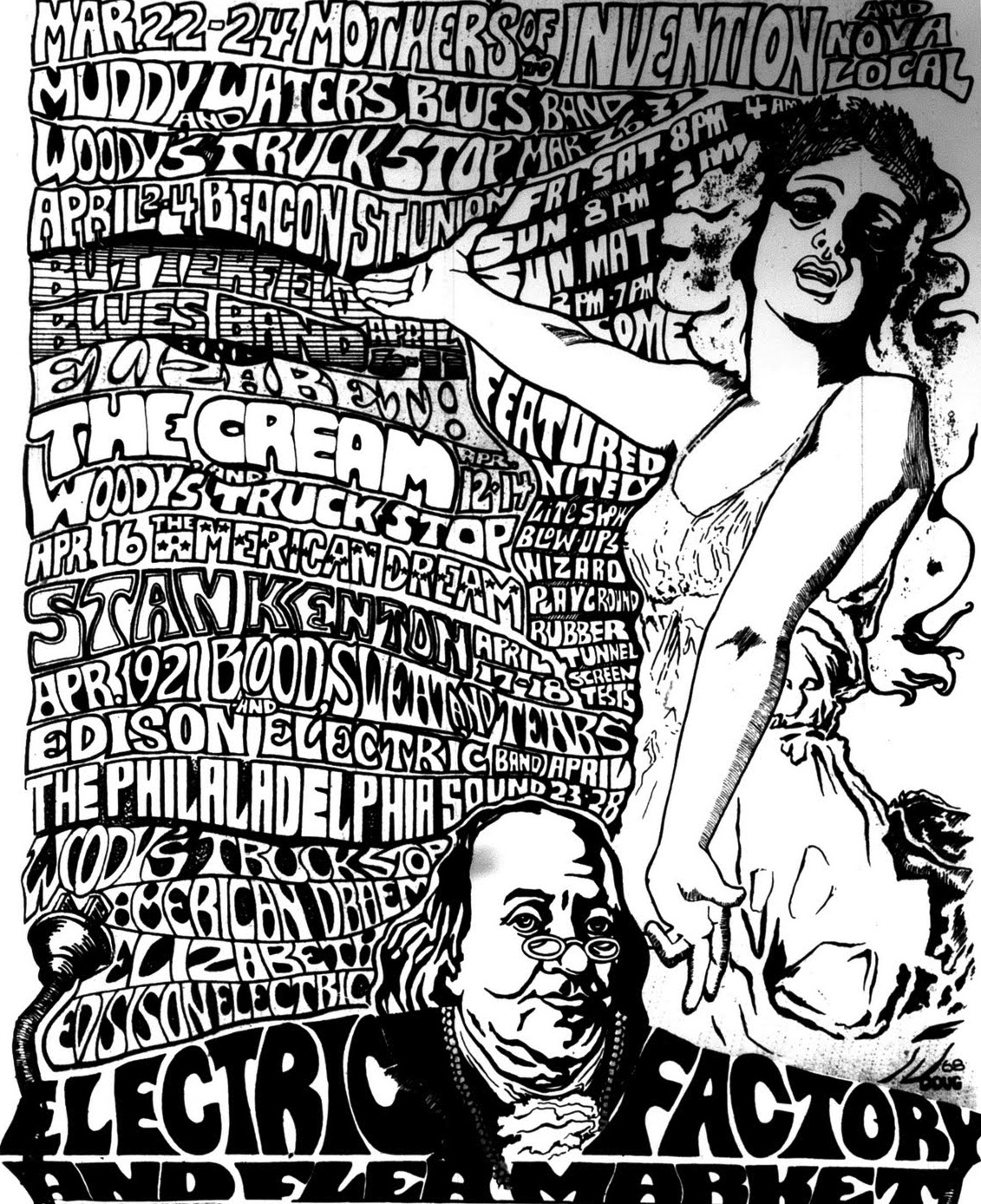

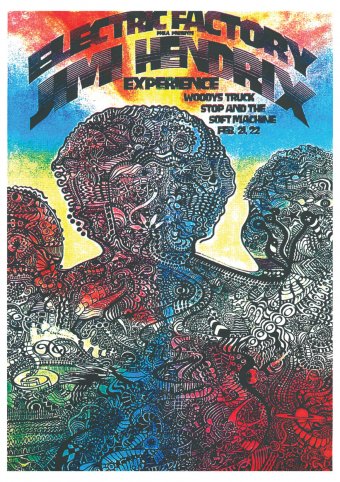

ADAM GOPNIK: Oh, generally positive, are you kidding? Listen, I was blessed with happy and enchanted childhood. When I go back and I walk the streets  of West Philadelphia were I grew up, as everyone does, the difference between the scale and enchantment between my memory and the reality of course is always there. But no, I loved it, I loved the streets of West Philadelphia, I loved the campus at Penn, I was a Phillies fan back in the old Shibe Park, as my dad calls it, Connie Mack Stadium as it was already. My grandfather ran a little grocery store up near Spring Garden and that was one of my key memories because I would go and work there, supposedly, every Saturday, you know, put on a white apron and work the cash register up there. He was a wonderful man who had started off as a wholesaler and his father had a wholesale business down in the wholesale market and a butcher at Penn Fruit, you probably don’t remember what Penn Fruit was but it was a chain of supermarkets. Then he had his own little store for about 30 years. So yeah, I remember when I got a little bit older we would sneak into the Electric Factory, you probably don’t recall but it was a great rock club that was down there, and I got to hear Jimi Hendrix and the Incredible String Band and God knows who else. Then I was also acting at that time, for a brief and very productive period Andre Gregory, the director, head of the theater down on South Street called Theatre of the Living Arts, which is no longer a stage theater, but for about five years he ran that and I was sort of the kid actor in the company. So I did a lot of avant garde theater and I also did some TV commercials in Philadelphia. We had Big Brothers of America, do you remember Big Brothers of America?

of West Philadelphia were I grew up, as everyone does, the difference between the scale and enchantment between my memory and the reality of course is always there. But no, I loved it, I loved the streets of West Philadelphia, I loved the campus at Penn, I was a Phillies fan back in the old Shibe Park, as my dad calls it, Connie Mack Stadium as it was already. My grandfather ran a little grocery store up near Spring Garden and that was one of my key memories because I would go and work there, supposedly, every Saturday, you know, put on a white apron and work the cash register up there. He was a wonderful man who had started off as a wholesaler and his father had a wholesale business down in the wholesale market and a butcher at Penn Fruit, you probably don’t remember what Penn Fruit was but it was a chain of supermarkets. Then he had his own little store for about 30 years. So yeah, I remember when I got a little bit older we would sneak into the Electric Factory, you probably don’t recall but it was a great rock club that was down there, and I got to hear Jimi Hendrix and the Incredible String Band and God knows who else. Then I was also acting at that time, for a brief and very productive period Andre Gregory, the director, head of the theater down on South Street called Theatre of the Living Arts, which is no longer a stage theater, but for about five years he ran that and I was sort of the kid actor in the company. So I did a lot of avant garde theater and I also did some TV commercials in Philadelphia. We had Big Brothers of America, do you remember Big Brothers of America?

PHAWKER: Oh, sure. I had one.

ADAM GOPNIK: Did you really? I don’t know if they still exist in this pedophile paranoid world. Even though I had five brothers and sisters and an extremely present father, I was the TV boy for Big Brothers of America. If anybody remembers back that far I used to do a commercial on Philadelphia television where I would say, “Won’t you be a big brother to someone like me, please?”

PHAWKER: I remember those commercials growing up, what year would that have been?

ADAM GOPNIK: That would have been from ’65 til ’68.

PHAWKER: Yeah, I was born in ’66, I guess they continued that commercial with other young boys.

ADAM GOPNIK: Other fatherless or other pseudo-fatherless boys. Philadelphia Magazine asked me to write something about remembering Philadelphia and the heart at Franklin Institute, which we used to be terrified of, along with the Franklin Institute generally.

PHAWKER: That’s fascinating that you were part of TLA, I’m well-acquainted with that actually. I did a very lengthy oral history of the origins of South Street and obviously that was the very beginnings of what became modern day South Street.

ADAM GOPNIK: I can remember as a kid being on South Street and it was still pretty slummy as we used to call it, there was a combination, there was some old kind of Jewish cafeteria down there but that was about it. When I go down there now, I don’t recognize the place.

PHAWKER: Yeah, it’s sort of more Haight-Ashbury. It was a Jewish retail district, that was one of the disembarking points for a lot of people coming over. It was also oddly enough the wedding dress district as well.

PHAWKER: Yeah, it’s sort of more Haight-Ashbury. It was a Jewish retail district, that was one of the disembarking points for a lot of people coming over. It was also oddly enough the wedding dress district as well.

ADAM GOPNIK: Huh, that escaped my juvenile eye, but I remember the Jewish cafeteria very well. You know, my father’s family, I don’t know how deep in the weeds you wanna get, were actually in – my father’s mother’s family were actually all in the garment business and they had a store down there as well, but that was already gone by the time I was a kid.

PHAWKER: And yes, I do know about the old school Electric Factory, any shows you can remember off the top of your head? You said you saw Hendrix?

ADAM GOPNIK: I remember seeing Hendrix. Double check this, but apparently he played in April of ’69, when I would have been down visiting a friend, we’d already moved but I would come down to my grandparents’ place. I saw the Incredible String Band, who nobody now remembers, who were actually very good. Do you remember the Incredible String Band?

PHAWKER: Well, I don’t remember them but I know who they are.

ADAM GOPNIK: It’s funny, I always tease my son by saying that my friend Jan, who is still in Philadelphia and was my best friend then, and I would go to the Electric Factory and sneak in, and we thought Hendrix was great but we also thought the Incredible String Band was great. He says, “the Incredible String Band, what was that, dad?” Well I looked them up online and they have a whole cult following.

PHAWKER: Oh very much so, Brit psych-folk. Hangman’s Beautiful Daughter. They definitely have been an influence on a certain strain of indie rockers.

ADAM GOPNIK: I remember it like it was yesterday, I looked it up and he was at the Electric Factory, as you know those Hendrix sites where they basically know and trace where he was everyday, which Strat he was playing, and so on. So yeah, I saw him there as well. And there used to be a wonderful little club – man, you’re pulling all this stuff out – called Second Fret.

PHAWKER: Sure, I know about the Second Fret.

ADAM GOPNIK: There was a local band called Elizabeth who we used to see all the time. There was another local band called Sweet Stavin’ and Chain. And another local band called Woody’s Truck Stop, I think they went on to become The Nazz, do you remember The Nazz?

PHAWKER: Of course, Todd Rundgren’s band, from Upper Darby.

ADAM GOPNIK: And I think Todd Rundgren might have been in Woody’s Truck Stop, but I’m not sure about that [He did, indeed.–The Ed.]. In any case, those were the places we went and hung out.

PHAWKER: At what point did you realize that writing was your calling?

ADAM GOPNIK: In Philadelphia when I was a kid, I’ve told this story before but it’s a true one. When I was about 10 years old, I wanted very much to go  see a Man From U.N.C.L.E. movie. I remember it was playing at the Stanton Theater downtown, and I asked my parents and they said, “Yes, absolutely you can go see it.” But then something came up between Monday and Friday, and they said, “No, we’re all going to see something else on Saturday so you can’t do it.” I was so indignant about it that I sat down and wrote them a 10 page letter, diagnosing the injustice of this last minute decision, how much I hated school and how I’d been looking forward to this all week long, it was the only thing I was looking forward to it and they were denying me. I slipped it under their door and then went to bed. The next morning my father said, “Hey, I read your very good letter. That really persuaded me, I had no idea you felt so strongly about this, of course you can go.” And they took me and dropped me off at the Stanton Theater. [That’s when I realized that] if you organize your emotions in sentences, you can have an effect on people that you could never have if you just express your emotions in words and talk. That was a kind of key moment for me. I realized that was both what I was interested in and what I was good at.

see a Man From U.N.C.L.E. movie. I remember it was playing at the Stanton Theater downtown, and I asked my parents and they said, “Yes, absolutely you can go see it.” But then something came up between Monday and Friday, and they said, “No, we’re all going to see something else on Saturday so you can’t do it.” I was so indignant about it that I sat down and wrote them a 10 page letter, diagnosing the injustice of this last minute decision, how much I hated school and how I’d been looking forward to this all week long, it was the only thing I was looking forward to it and they were denying me. I slipped it under their door and then went to bed. The next morning my father said, “Hey, I read your very good letter. That really persuaded me, I had no idea you felt so strongly about this, of course you can go.” And they took me and dropped me off at the Stanton Theater. [That’s when I realized that] if you organize your emotions in sentences, you can have an effect on people that you could never have if you just express your emotions in words and talk. That was a kind of key moment for me. I realized that was both what I was interested in and what I was good at.

PHAWKER: You realized you could become the author of your fate. What’s the typical workday in the life of Adam Gopnik?

ADAM GOPNIK: It’s boring beyond belief. We get up early to get the kids to school, I have extremely strong coffee that my wife, who is of Icelandic stock, makes and drinks all day. Extremely powerful. Two cups. Then I start writing at about 8:30 or 9:00, then I keep writing until 3:30 or 4:00 and I break for a bowl of soup sometime in the middle. I listen to my Pandora, Rolling Stones edition. Three times a week I’ll go into the magazine at my office at the New Yorker if I’m closing a piece or to fact check. Then I’ll go shopping for dinner afterwards around 6:00, open a bottle of wine, we all have dinner together, then we try to corral the kids into their homework, eventually to bed, and then the whole thing starts over again. That’s my rhythm.

PHAWKER: How much do you actually labor over your prose? Are you first thought best thought, or do you do a lot of rewriting?

ADAM GOPNIK: Endless amounts of rewriting, we usually go through 10 or 11 proofs per piece typically at the magazine. I have a funny way of working, I always need to know what my first sentence is and what my last sentence is in order to be working. Then I try and knit the two things together from the other end, then when I’m finally sort of set up I’ll hand it in to my editor and we’ll work on it together. And then I have a wonderful copy editor — copy editor is not a noble enough term for what she does — and we’ll go over it sentence by sentence if I say, we’ll revise it four or five times at least. So I’m a perpetually dissatisfied writer and I tend to feel that you never really finish a piece, you just abandon it.

ADAM GOPNIK: Endless amounts of rewriting, we usually go through 10 or 11 proofs per piece typically at the magazine. I have a funny way of working, I always need to know what my first sentence is and what my last sentence is in order to be working. Then I try and knit the two things together from the other end, then when I’m finally sort of set up I’ll hand it in to my editor and we’ll work on it together. And then I have a wonderful copy editor — copy editor is not a noble enough term for what she does — and we’ll go over it sentence by sentence if I say, we’ll revise it four or five times at least. So I’m a perpetually dissatisfied writer and I tend to feel that you never really finish a piece, you just abandon it.

PHAWKER: That’s what Keith Richards said about writing songs, you don’t really finish them, you just stop.

ADAM GOPNIK: Exactly.

PHAWKER: Moving forward to your 2009 book, Angels & Ages: A Short Book About Darwin, Lincoln, and Modern Life. What is the connection between Lincoln and Darwin?

ADAM GOPNIK: The factual connection is they were both born on the same day: February 12th, 1809. The subject of the book is really the creation of the language of modern liberalism in the 19th century, both in science in Darwin’s work, not just his discoveries but his entire way of writing and expressing himself, and then the politics of Lincoln, through Lincoln’s greatness not just as a leader but as a writer. So it’s about how you write the mind of liberalism in the broad political sense, not in the local kind of Western sense, but in the larger historical sense. It’s about the language of liberalism and it takes advantage of this remarkable coincidence that Darwin and Lincoln were born on the same day to do it.

PHAWKER: In 2000 you gave an interview to the literary website Identity Theory upon having just returned from a five year stay in Paris, I wanna quote this at length if you’ll indulge me here because I think it bears repeating and then I would like you to respond to it: “To some degree – I don’t want to make too much of this – I got radicalized in Paris even though we had a very beautiful existence and that was the essence of it. Things that I had always taken for granted in America, forgive me if this sounds like the same fairly weary stuff – violence, incarceration, capital punishment, free-for-all medical care – you may deplore them, curse them, but they seem to you to be part of the normal realm of existence in America. Well, they are not. They’re the exception. They are the very strange exception to the general role of prosperous societies at the end of the twentieth century, the beginning of the third millennium.” That was 2000, 11 years on, what do you make of those remarks?

ADAM GOPNIK: I would redouble them like when you redouble a bid. I would redouble them both from the point of view of having lived in Europe and also from a Canadian point of view, we’re right now going through difficulties, my wife’s mother is aging and has difficulties that very old people, she’s in her 90s, have in Canada, in Alberta. And though a lot of it is painful and difficult, none of it costs anything. All of it is paid for and that’s true right through everybody’s life, Canadian medical care has its flaws but it genuinely works and the idea that something like Obamacare, which is the most partial, tentative attempt to bring American medical care up to grade, that this should be controversial I think is not just crazy, but even depressing that anyone should find something so commonplace in prosperous societies to be controversial at all. So yes, I feel that that’s more true than ever. I’m in the middle of writing a long piece about epidemic of incarceration for the magazine, which I hope will be out in four or five weeks, and there again we’re talking about we currently have more men in prison than Stalin did in The Gulag Archipelago, they’re in somewhat better conditions but the numbers are greater. Those things are things that Americans that take for granted as just a feature of the landscape and, no, they’re not.

PHAWKER: Are you tackling the private prison industry in this piece?

ADAM GOPNIK: Yes, exactly. We have a kind of political interest group who want to see more men in prison. It’s profoundly, not only inhumane, but not democratic, not that prison should be a means of last resort for the people who cannot be helped or prevented in any other way, but that we wanna grow prisons because there are people who want to make profits from them. It’s obscene.

PHAWKER: It is obscene. It’s immoral.

ADAM GOPNIK: I feel that way more passionately than ever, I’ve tried to do what little a writer can do with art, I’ve done hearings and debates with my friend Malcolm Gladwell about national healthcare, and we tried to fight the good fight.

PHAWKER: I’m sorry, did you say that Gladwell is opposed to reform?

ADAM GOPNIK: Gladwell was [opposed to reform]. Ten years ago we did a debate for Washington Monthly Magazine, and at that point he was, he was more of a libertarian, he has totally come around now to the other side and has written very eloquently about the need for Canadian-style system in the States.

PHAWKER: Just to finish up on the prison thing for a second, when there is a profit motive for keeping people in prison, the incentive is to put as many people in prison as possible for as long as possible.

ADAM GOPNIK: That’s the way it works, it’s not dissimilar in medical care problems, the free market is a wonderful thing that brings enormous prosperity in many ways, but it’s not an all purpose solvent, there are things like medical care and imprisonment that cannot be solved with a market model. The reason why we have such insanely high costs for medical care in the United States is because we’re driven by a profit motive, it’s not a good way to try and organize medical care when it’s something that everybody will need and nobody can really price shop for, one of the options is I’ll do without it. Yes, the  idea of injecting market values into non-market precincts of life is an American illness. That’s not to say that the market values are bad, they just aren’t appropriate in many parts of life.

idea of injecting market values into non-market precincts of life is an American illness. That’s not to say that the market values are bad, they just aren’t appropriate in many parts of life.

PHAWKER: Agreed. Moving on, your new book The Table Comes First, is in part a meditation on the evolution of the modern day palate, is that a fair assessment?

ADAM GOPNIK: Yes, absolutely.

PHAWKER: Which you trace all the way back to France in the 18th century, can you elaborate on that?

ADAM GOPNIK: Obviously one of the paradoxes of writing about food is that everybody on the planet, if they’re lucky, eats every day. In that way it’s closer to breathing, or contemplating or copulating than it is to writing poetry or composing music, it’s a natural activity. And yet, it has a very specific cultural style in the way we do it and that’s what I’m trying to trace in this book. The first two chapters in the book are about the pillars of modern eating, we either go out to eat at a restaurant or cafe, or we stay home and cook. If we’re going out to eat we go to a restaurant, where did the restaurant come from? Is this an institution that has always been there or does it have a particular character because of history? And similarly what I wanted to find out about recipes, is the recipe book something that’s always been there or does it have a particular character that comes out of its history? So those are the first two chapters. What captured me about the history of the restaurant is that it’s such a relatively modern invention, there’s a lot of debate about what exact moment it appears, but everybody agrees that it appears for the first time in Paris just before the French Revolution. All of the kind of rituals we take part in every week or every night, depending on how often you go out, were made – the menu, the hidden kitchen, the idea of a restaurant as a place for courtship, all of those things were part of it. As I explained in the book, my own first memorable experience of a restaurant was the old Howard Johnsons on City Line Avenue that my parents took me to on my 10th birthday. What astonishes me is that everything I loved about it, this simple HoJos, was continuous with the very first appearance of the restaurant in Paris 200 years ago. It’s one of those institutions that’s sort of transparent to us, we’re not aware that it has any particular history or any particular special texture, but it does. It’s this whole empire of dining that goes around the world, and I’m very interested in that. More generally what I’m trying to do in this book is, well, many things, but more than anything else to try instead of thinking about food and eating from the ground up alone, that is from a question of agriculture and sustainability, all which are terrifically important, but trying to think about eating sort of from the mind down, in terms of a much broader humane horizon that it affects the way we eat, what we eat, how we eat, and what we think is good to eat.

PHAWKER: Is the rise of the restaurant, is that when eating goes from mere subsistence to pleasure and social interaction?

ADAM GOPNIK: I wouldn’t put it quite that simply because of course before then people were – every nation and every tribe has eating rituals. One of the fascinating things is you can’t find any people who don’t have dietary rules, dietary restrictions, forms of eating, what you eat first, what you eat later, so far as anybody knows from the very first appearance of wine and alcohol, they always had a ritual purpose. It’s not unique to modern times that we invoke so much meaning. But there are particular types of meaning that we’ve been giving food since modern times began. The idea, for instance as I said a moment ago, the natural place to conduct a courtship is over a restaurant table, it’s a safe place where unattached men and unattached women can meet and court, that’s a modern idea that is now almost universalized. The habit, as I say in the book, at a kind of simple level, of having a meal that begins with wine and proceeds to coffee – that’s something, again, that we take for granted but is a feature of the French restaurant and its first appearance. Selling coffee and spirits in the same space was heretofore unheard of.

PHAWKER: What is your take on factory farming? Presumably you’re not a fan, to say the least, and not that you’re an expert on this, but is it possible to feed the world otherwise in your estimation?

ADAM GOPNIK: I think this is a big question, and what I try to do in the book – I’m not an expert on this and I don’t pretend to be – what I do try and do is be a little bit skeptical of a too easy assertion that factory farming is utterly evil and they should get rid of it and return to old fashioned ways of sustainable farming. I think that terribly underestimates the reality of the past, the history of food in the past is largely the history of famine, to overlook that is I think very foolish and non-historical. So obviously all of the things we deplore about factory farming are linked to the relative abundance of American and European life right now. Should we amend it, should we change it? Absolutely, of course, but I think we should never become sentimental about some sort of lost medieval agricultural paradise that didn’t exist.

PHAWKER: Most of your waking hours were spent procuring food.

ADAM GOPNIK: The agricultural revolution, as many people have pointed out, was a catastrophe to human beings, it turned them from free foragers into slaves of the earth, nothing to be nostalgic about because of life or what traditional agriculture meant. I think we need to reform contemporary agriculture, I don’t think there’s any question. I think there are people doing wonderful inventive work but we need to do it in the clear right away and not be sentimental about an imaginary past.

ADAM GOPNIK: The agricultural revolution, as many people have pointed out, was a catastrophe to human beings, it turned them from free foragers into slaves of the earth, nothing to be nostalgic about because of life or what traditional agriculture meant. I think we need to reform contemporary agriculture, I don’t think there’s any question. I think there are people doing wonderful inventive work but we need to do it in the clear right away and not be sentimental about an imaginary past.

PHAWKER: You’ve written a pair of children’s books, what was the motivation to pursue that form?

ADAM GOPNIK: The truthful and sort of modest thing to say is that I have two kids and I was telling stories to them and those stories turned into books, but at another level I love the form, I just love fantasy adventures. I’m writing a piece right now, after we hang up, about Tolkien and Tolkien’s influence, and I read Tolkien for the first time in Philadelphia when I was 11 and it changed my life. I read along with P.H. White and the Mary Poppins books and so on. I love the form, love reading them, and I realized at a certain point I felt obliged to write a novel, I would sooner write a fantasy novel, sooner write a children’s novel than write a proper grown up novel and so I did.

PHAWKER: How do you get into the mind of your reader? How do you discern between what will connect with them and what won’t, especially when you aren’t that age anymore?

ADAM GOPNIK: One way is you read to them. I read those books to the kids they were dedicated to, and with the second one, Steps Across The Water the book I wrote with my daughter in mind, I actually took it to her second and third grade class and read it out loud, the teachers were very generous for letting me do that, and you watch their faces, you see what they respond to and what they don’t respond to. In Steps Across The Water for example, there was a minor character who was a tiny dog, a dog no bigger than your thumbnail, and the kids lit up, and so that dog became more important in the book. It’s like any other kind of writing, in a sense you write for yourself, you write for the child you once were, you try and imagine, try to remember what it was that served you as a reader then. And to be truthful, it’s like any other kind of writing, there are some who care for it and some who don’t. The nicest thing that can happen, that does happen to me on the long road I go out on promoting books, is there was a kid who was really stirred by those books. And it doesn’t happen every day, I’m not J.K. Rowling, but when it does happen it’s probably the most gratifying thing that does happen.

PHAWKER: Another quote I wanted to read back to you from that Identity Theory interview, again indulge me because I just think this is so beautifully put and I would like to enter it into the record: “Essayists generally – and certainly me particularly – tend to be more like performers than novelists. Novelists are like architects or builders. They are willing to sit in a room for five or six years and build something and they at some level don’t give a damn what the public thinks. They want to make a cathedral for themselves to live in and then they open the doors. If you come in to worship that’s fine. And if you don’t that’s fine, too. Essayists aren’t like that. At least this one isn’t. You have to have a bit of the ham in you. You like to do the thing and feel that the people are reacting.” First of all, great, second of all is the novel still relevant a decade into the 21st century?

ADAM GOPNIK: Some novels clearly are, Jon Franzen’s books obviously reached an enormous public, terrifically well done, they reached enormous public and the cover of Time Magazine and so on. I guess you could extend that to Michael Chabon and other wonderful writers who are around. I sometimes feel that the novel proper, the big novel, it’s a little bit like the first tragedy in the 18th century, everybody feels obliged to write it and we all give an enormous ethical credit for writing them but we don’t always read them.

PHAWKER: What are your thoughts on the slow dissolve of print into the digital ether?

ADAM GOPNIK: Oh God…you know, I’m like everybody, I did a long piece in the magazine about Internet culture about six or seven months ago and I identified the three schools of commentators on the Internet and its effect on writing. There’s the never-betters, the people who believe that this new digital technology is just unleashing this huge democratic wave of information and creativity; the better-nevers, who people who believe that the whole thing  should have never happened, like Nicholas Carr, for example, who think it is eliminating ruminative long-range and long-form thoughts from the world. And then the last group, the ever-wanters, the people who believe that at every moment in history there is a new technology that seems to be actively devastating every value we held in every form we love, that this is always the case – it was true about printing in the 16th century and it was true about television and radio in the middle of the 20th century. Nobody remembers how destructive television was supposed to be to literature, now we look back on television fondly as this wonderful communal activity. So how do I feel about it? When I wake up in the morning and I have my coffee and I read all the blogs and I check what we’re doing in the New Yorker online I’m a real never-better, about the middle of the day when I’m working on the book and I realize that books are a dying form I’m a better-never, the rest of the time I’m an ever-wanter and I oscillate between those stages every day.

should have never happened, like Nicholas Carr, for example, who think it is eliminating ruminative long-range and long-form thoughts from the world. And then the last group, the ever-wanters, the people who believe that at every moment in history there is a new technology that seems to be actively devastating every value we held in every form we love, that this is always the case – it was true about printing in the 16th century and it was true about television and radio in the middle of the 20th century. Nobody remembers how destructive television was supposed to be to literature, now we look back on television fondly as this wonderful communal activity. So how do I feel about it? When I wake up in the morning and I have my coffee and I read all the blogs and I check what we’re doing in the New Yorker online I’m a real never-better, about the middle of the day when I’m working on the book and I realize that books are a dying form I’m a better-never, the rest of the time I’m an ever-wanter and I oscillate between those stages every day.

PHAWKER: That’s a good place to be. Will the New Yorker continue to thrive as a digital-only product and I don’t mean that just in the economic sense, that’s a whole other discussion, I’m referring to the thisness of the New Yorker. Is a magazine still a magazine when it’s no longer words on a page, it’s words on a screen?

ADAM GOPNIK: It’s another question in my life and I guess in a broader sense the life of everybody who cares about the magazine. So far so good. I say that cautiously but I say it affirmatively. We’ve now made the transition to the iPad and having an iPad app and that has gone extremely well. And when you have the iPad it’s potentially a magazine, it’s on a screen rather than on paper but it’s recognizably the New Yorker. You read it the way you read the magazine. My hope is that eventually we’ll get to a kind of model where we can deliver the magazine to you on any platform – on paper, on the iPad, online. The one thing all of us who labor in that shop find encouraging, length of pieces doesn’t seem to be a barrier to people’s attachment to them. When you look at what is the most looked at thing on the website, often it is very long pieces. Malcolm Gladwell on Steve Jobs. I did a long piece, 15,000 words on the historical Jesus about a year ago, and for weeks that was the most clicked on thing we had. The good news is length itself doesn’t seem to be a barrier to people wanting to read online.

PHAWKER: What advice would you offer to anybody aspiring to write for a living in this day and age?

ADAM GOPNIK: It’s very much harder now, I’m sure, than when I was starting out. The first job I had was as a fashion copy editor with GQ magazine. Those jobs are rarer now than they were then. So it’s harder. But being a writer has always been hard. When Samuel Johnson came to London in the 1750s, he was caught between two models of paying for literature. In the past there were the rich who paid authors directly and in the future would be a big middle class audience that would subscribe to things and he was caught between the two — you had an enormous industry for literature and an appetite for literature and no way to monetize literature. This has happened and again, I largely believe it will right itself. There may be many a storm before all the boats get righted, but they will sooner or later. Finally, I don’t think anybody, for a hundred years at least, has chosen writing as a vocation because they believe it’s going to pay. We were talking about Tolkien, that was the most successful book probably ever written, and the last thing in the world that Tolkien was thinking as he wrote it was this is a commercial proposition. So we all write out of necessity and not out of commercial speculation, so I suspect as long as that urge burns inside of people they’ll go on writing.

PHAWKER: Do you think that more people read now than ever before or was there some other golden era where more people read or more people read seriously?

ADAM GOPNIK: I think more people read now than have ever read, I think that’s true in hard numbers because there are more people now. The novel was the great Victorian popular genre. On the other hand there were people who were literate enough and had the leisure time to read. Malcolm Gladwell said, and he’s a very wise guy, ‘We’ve got a million subscribers to the New Yorker, round it off to about two million readers. That’s as many as you could possibly hope for, five times as many or more than that as Shakespeare ever had, twice as many as Charles Dickens ever had, it’s all the readers you need.’ I don’t think it’s a problem with a disappearing audience for writing, I think it’s a problem with connecting that audience to writers that provides a way for the writers to make a living.