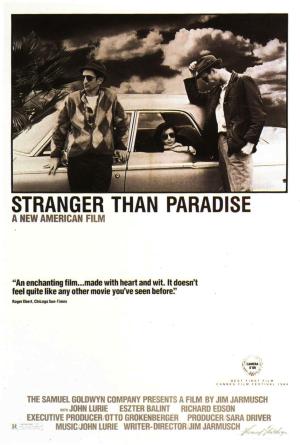

EDITOR’S NOTE: This interview with Stranger Than Paradise star Eszter Balint originally published back in 2015. We are reprising here today for two reasons, three actually: 1. It’s interesting, if you’re into, like, interesting things 2. It’s almost certainly the most in-depth, comprehensive and exhaustive Eszter Balint career overview ever published (hey, somebody had to do it) 3. She has a supporting role in the Jim Jarmusch zombie comedy (zom-com?) The Dead Don’t Die, which opens Friday.

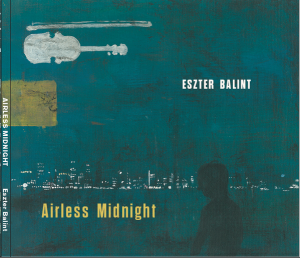

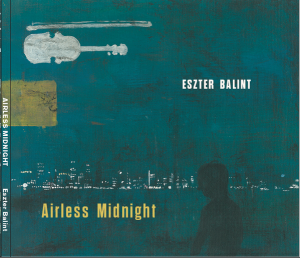

BY JONATHAN VALANIA Eszter Balint, best known as the then-16-year-old star of Jim Jarmusch’s career-making, tide-changing, genre-defining 1984 indie flick Stranger Than Paradise, has lot of balls in the air right now. Her acting career was revived recently when Louis CK cast her as his non-English speaking Hungarian love interest for six episodes of Louie. In addition to a lengthy filmography and an impressive cast of co-stars, Balint is a classically-trained singer/violinist and a darkly elegant songwriter, in the Leonard Cohen/Lou Reed meaning of the word, who writes these inscrutable noirish tone poems telegraphing the anguished midnight of the soul. Such is the case with her new album, Airless Midnight, a dusky, sad-eyed album-long meditation on magic and loss, written in the wake of the death of her father, the noted experimental playwright Stephan Balint. To mark the release of Airless Midnight, Phawker conducted a comprehensive five-hour interview with Balint. By her admission, it’s the most in-depth and revealing interview she’s ever done. Balint has done a lot of living in her 49 years.

BY JONATHAN VALANIA Eszter Balint, best known as the then-16-year-old star of Jim Jarmusch’s career-making, tide-changing, genre-defining 1984 indie flick Stranger Than Paradise, has lot of balls in the air right now. Her acting career was revived recently when Louis CK cast her as his non-English speaking Hungarian love interest for six episodes of Louie. In addition to a lengthy filmography and an impressive cast of co-stars, Balint is a classically-trained singer/violinist and a darkly elegant songwriter, in the Leonard Cohen/Lou Reed meaning of the word, who writes these inscrutable noirish tone poems telegraphing the anguished midnight of the soul. Such is the case with her new album, Airless Midnight, a dusky, sad-eyed album-long meditation on magic and loss, written in the wake of the death of her father, the noted experimental playwright Stephan Balint. To mark the release of Airless Midnight, Phawker conducted a comprehensive five-hour interview with Balint. By her admission, it’s the most in-depth and revealing interview she’s ever done. Balint has done a lot of living in her 49 years.

Back in the 1970’s, Stephan Balint was a high profile dissident in Hungary who fled to New York in 1977 with his family — including 10 year old Eszter — when his work ran afoul of the Communist authorities and set up an off-off-Broadway theater in Chelsea that became a gathering  place for many soon-to-be-famous denizens of the NYC underground art and music scenes: Susan Sontag, Jonathan Demme, Sun Ra, John Lurie, Jim Jarmusch and Screaming Jay Hawkins, to name but a few. These are the people Eszter Balint rubbed elbows with when she was a teenager. She was very good friends with Jean Michel Basquiat and played, at his behest, on “Beat Bop,” the little-known hip-hop single he recorded before his death. Rubbed elbows with Julian Schnabel and Rainer Werner Fassbinder After Stranger Than Paradise became an underground hit she was cast in Woody Allen’s Shadows & Fog where she worked with Mia Farrow and John Malkovich, as well as Steve Buscemi’s Trees Lounge and starred opposite David Bowie in The Linguini Incident. From there she transitioned into music, writing, recording and releasing two well-received albums in the early aughts, appeared on the second album by Marc Ribot’s legendary Los Cubanos Postizos and was a touring member of Cerarmic Dog, as well as playing on Swans and Angels Of Light albums at the behest of Michael Gira, who does not suffer fools gladly. Neither does Eszter Balint.

place for many soon-to-be-famous denizens of the NYC underground art and music scenes: Susan Sontag, Jonathan Demme, Sun Ra, John Lurie, Jim Jarmusch and Screaming Jay Hawkins, to name but a few. These are the people Eszter Balint rubbed elbows with when she was a teenager. She was very good friends with Jean Michel Basquiat and played, at his behest, on “Beat Bop,” the little-known hip-hop single he recorded before his death. Rubbed elbows with Julian Schnabel and Rainer Werner Fassbinder After Stranger Than Paradise became an underground hit she was cast in Woody Allen’s Shadows & Fog where she worked with Mia Farrow and John Malkovich, as well as Steve Buscemi’s Trees Lounge and starred opposite David Bowie in The Linguini Incident. From there she transitioned into music, writing, recording and releasing two well-received albums in the early aughts, appeared on the second album by Marc Ribot’s legendary Los Cubanos Postizos and was a touring member of Cerarmic Dog, as well as playing on Swans and Angels Of Light albums at the behest of Michael Gira, who does not suffer fools gladly. Neither does Eszter Balint.

PHAWKER: So let’s go back to the beginning here. Your father Stephan Balint [pictured, below right] was a purveyor of experimental theater, a writer, an actor, producer, harassed by the communist authorities, banned from performing in public theater in Hungary had to put on plays in people’s apartments and houses, things like that. Is that all correct?

ESZTER BALINT: Yeah you’ve done your fact checking.. Very good!

PHAWKER: And so he flees to America in pursuit of freedom like many, and brings you along with your mother, and you have a brother too, right?

ESZTER BALINT: We actually went to France first, as part of a group; it was an ensemble situation, and he was one of the several founders of what became later known as Squat Theater. So we were a collective, 4 children and 6 adults originally, when we left Budapest. We lived in France for a year and a half, travelling a lot, then moved to the States in ‘77. I have a much younger half brother living in Europe – but he came way later.

PHAWKER: Right. And they set up shop, where on 23rd street?

ESZTER BALINT: Yeah in the Chelsea Hotel initially for about six months.

PHAWKER: You lived in the Chelsea Hotel?

ESZTER BALINT: I did.

PHAWKER: What do you remember about that?

ESZTER BALINT: It was crazy, but you know my whole life was pretty crazy so I felt at home. I remember one woman, resident of the hotel befriended us. The first time I saw her she seemed like a perfectly nice girl, she was cute, young, had short brown hair I remember., And the second time I saw her she entered the room we all shared stark naked, and I realized she was stark naked mad, like many who lived at the Chelsea.. I also remember sitting in the lobby during the huge ‘77 blackout. Everybody congregated down there, people played their acoustic guitars, and it was a very communal spirit of freaks. I was a kid, it was fun for me, an adventure. What more could a kid ask for?

PHAWKER: Were you living there when Sid Vicious stabbed Nancy Spungen to death?

ESZTER BALINT: It was around the same time but I wasn’t living there anymore, I believe by that time we had settled in the storefront that became our home, down the street. However, this is a total side anecdote but much later. In the mid-80’s my father put on a little play that was part of one of the early site specific projects, I believe by En Garde, to whi ch he/ Squat was invited to participate. And the whole series took place at the Chelsea Hotel. My father’s piece was a demented adaptation of Little House on the Prairie, performed in one of the rooms, with a goat as one of the sisters. This was similar in some ways to the apartment theater the company was doing in Hungary, when they were banned by the authorities from any public venues – with the audience set up inside the room. So it was familiar terrain for my father. Anyway, I distinctly remember one of the events, which I think followed my father’s piece, was a supremely funny wonderful piece by Penny Arcade about the Sid Vicious, Nancy Spungen thing. It was powerful seeing it in one of the rooms at the Chelsea. I remember being pretty floored by that performance.

ch he/ Squat was invited to participate. And the whole series took place at the Chelsea Hotel. My father’s piece was a demented adaptation of Little House on the Prairie, performed in one of the rooms, with a goat as one of the sisters. This was similar in some ways to the apartment theater the company was doing in Hungary, when they were banned by the authorities from any public venues – with the audience set up inside the room. So it was familiar terrain for my father. Anyway, I distinctly remember one of the events, which I think followed my father’s piece, was a supremely funny wonderful piece by Penny Arcade about the Sid Vicious, Nancy Spungen thing. It was powerful seeing it in one of the rooms at the Chelsea. I remember being pretty floored by that performance.

PHAWKER: They acted out the murder?

ESZTER BALINT: Yeah. they acted out the murder but it was a very sort of dark comedic take on it. I remember there was a pizza delivery boy who somehow took on a pivotal role in the story.

PHAWKER: And then you lived at the Squat Theater, which was sort of a communal living space and performance space on 23rd street is that right?

ESZTER BALINT: Yes, there was a storefront theater that was at ground level and then there was a living room communal space where we – or the adults I should say – hashed out the play. Which consisted of a lot of hair pulling and pacing and yelling. And then there were large bedrooms spread out all over various floors in the building.

PHAWKER: Jonathan Demme was an audience member or regular hanger-on is that right?

ESZTER BALINT:He was an audience member, yes – where did you get that? I’m just curious.

PHAWKER: This might have been in your father’s New York Times obit. He tells a story about a play where two men pull up in a jeep outside and kidnap somebody from the play and drive off with them and you never see them again.

ESZTER BALINT: Yeah so Jonathan Demme was one of the people who came around and saw one or two of the plays and really liked them and had made some very generous public comments about them. But — not to drop names — but there were a few admirers.

PHAWKER: Drop some names, tell me who.

ESZTER BALINT: Well, Susan Sontag . So was Fassbinder – though he didn’t see us in New York, he filmed several of the plays at a theater festival in Germany. The director Peter Sellars. So some not too shabby creative peple.

PHAWKER: Yeah, I’ll say. And when plays were not going on this was a performance space? I’m getting this out of nowhere maybe Wikipedia. People like Defunkt and DNA and Sun Ra would perform or just hang out there?

ESZTER BALINT: Both. It was considered an important music venue at the time. So yes for a few years when we didn’t use the space to perform the plays, it would be transformed into a club with live concerts.

PHAWKER: Also around this time you played violin on a rap track by Basquiat. What do you remember about that experience?

ESZTER BALINT: It was a little intimidating.

PHAWKER: Because?

ESZTER BALINT: It wasn’t so much intimidating because of Basquiat, maybe a little as I had a lot of admiration for him, but we had been friends. I was very happy he asked me to be a part of it. But Rammellzee, who raps on the song, brought in some of his crew, and having them in the studio was definitely intimidating for me, I admired that early hip hop scene a lot as well, and I was this 15 or 16 year old girl who had studied classical violin, and I remember them sort of yelling in the studio during my take: “Funk it up, Funk it up!” That made me a little anxious. It’s hard to funk it up on the violin on the best of days. Not the world’s funkiest instrument.

PHAWKER: How did you become friends with Basquiat?

ESZTER BALINT: Well I think we met basically the same way I met all the people I knew at that time. He passed through Squat Theater, quite a few times, so that was one thing. And I also crossed paths with him at the other clubs I went to. It was really a scene – if you were in it, and I was, it was hard not to know the other people in it. I remember the first time I saw him, at Squat, but I don’t remember the exact time we actually met. I was in that movie Downtonwn 81- but we were friends by that time

PHAWKER: So this is 1980? He wasn’t a big art star at that point, was he? He was kind of not really discovered.

ESZTER BALINT: Well the record might have happened in ‘81 or 82. I can’t really remember the exact year. Things were just starting to really heat up in a big way for him around that time. But I had known him prior his break. Although he was always making art,and funnily he also had a very, “famous” vibe before being famous. I think maybe he badly want ed to be famous, and he had a lot of charisma.

ed to be famous, and he had a lot of charisma.

PHAWKER: Did you see the Basquiat biopic that Julian Schnabel made?

ESZTER BALINT: I did.

PHAWKER: Did it feel authentic to you?

ESZTER BALINT: It’s very hard to say. It was a difficult movie for me to watch. I think it has some wonderful things about it, Jeffrey Wright [the actor who portrayed Basquiat] was brilliant. But for me it felt odd, like watching a fictionalized part of my own life in some ways.. Not that it was my life, I’m not appropriating that. But I knew so many of the characters in the film; I was present at some of the events depicted,; it was a little too close to home. I couldn’t find my own comfortable place as a viewer.. So I can’t really objectively say how I feel about the film. Which I think is normal in this situation.

PHAWKER: Somewhere at this point is where you run into Jim Jarmusch, right? He was a Squat Theater regular?

ESZTER BALINT: Yeah I think that his early band may have played there, but he certainly came by and we had run into each other at other places where people were hanging out. I was good friends with John Lurie who was good friends with Jim. It all sounds very exotic now because it’s not really like that anymore anywhere but it was a big community of artists so it was normal to meet each other and do things together.

PHAWKER: Yeah it sounds pretty amazing. You’re right it’s not like that anymore, certainly not in New York. Now I’m curious, it doesn’t sound like any of these artistic adventures were profitable. I’m wondering how you were able to get by?

ESZTER BALINT: That’s a good question. ‘Barely’ is one answer. The other thing is that living in New York was a very different story back then. You didn’t need that much. People had all kinds of scams and schemes with incredible rent-stabilized apartments, where they paid anywhere from $100-200 for rent. We had great difficulty paying the rent, and were usually broke. just to put it bluntly. We got some grants, we traveled, performing our plays in Europe and occasionally in the States, and that brought in a little bit of cash, but certainly not enough to support everyone in the theater year round. The music venue may have started out as a business venture, it was actually spearheaded by somebody outside the theater who was a friend, but in the end I’m sure we lost more money on it than we made. Nobody at the theater had any business plan or business smarts. But we as a theater got a lot of help from supporters, including, for a time, the landlord. Then, at some point, the jig was up.

PHAWKER: So you’re a very young teenager at this point and typically an American teenager is sullen and rebellious and doesn’t like their parents. But it doesn’t sound like that was your experience.

ESZTER BALINT: It’s interesting. It was a little twisted around for me but everybody goes through their own thing. I kind of skipped the teenagehood stage all together, which may not have been a good thing. I cultivated friends when I was a teenager who were much older than me, I didn’t have teenager friends. I had young adult friends and considered myself an adult and tried to pass myself as being older than I was. I guess that was my version of rebellion; going out on my own, to the clubs, cultivating my own relationship with the people on the scene.

PHAWKER: When did you learn to speak English?

ESZTER BALINT: Very quickly after arriving here. In fact when we were living in France I was already learning English and by the time I came here I had some basics. You know how kids are they absorb like sponges. So I went to school and very quickly picked up the language.

PHAWKER: So how did you wind up starring in Stranger Than Paradise?

ESZTER BALINT: Jim asked me to do it and I’m not sure if it was his idea or John’s but I definitely had a closer, more established friendship with John at the time.. We’re really getting into the nitty-gritty of the life story here!

PHAWKER: Well, these are the kind of interviews we do. You’ve led a very very interesting life so I wanted to talk about this stuff. We’ll get to your new album too by the way. I’m not just pumping you for Stranger Than Paradise stories. But while we’re on the subject, I’m curious about the evolution of this. Is it right that you were 16 when it actually started production?

ESZTER BALINT: Yes, I believe I was 15 or 16 and Jim had a little bit of money for a short half hour film. He had a basic sketch of an idea, we kind of fleshed it out just a bit more during rehearsals in his apt. The short version was well-received and I think it played at some festivals. I think it turned out better than anyone expected. But then nothing happened for a long time, as he had no money to turn int into a feature, until he got some leftover film stock from Wim Wenders to finish the film. I believe it was leftover stock from The State of Things. I just recently learned that, which is personally funny to me because I love that film and also one of my dearest oldest friends who I’m still very close to is in it.

PHAWKER: So the finished film that I’ve seen included footage from that original short version of the film?

ESZTER BALINT: Yeah the short version was the first third, the New York segment. That was not touched after the original shoot. Just shot the other two segments, Cleveland and Florida.

PHAWKER: And you had one of the best lines that I still repeat to this day. Your character was obsessed with “I Put A Spell On You” by Screamin’ Jay Hawkins. At one point John Lurie’s character complains about you playing it all the time in the apartment and you go, with a heavy Hungarian accent, “Screamin’ Jay Hawkins is a wild man, so bug off!”

ESZTER BALINT: What was the question?

PHAWKER: There wasn’t one I just like saying that. Tell me about that song. Was that the first you’d been exposed to that, did you even know about Screamin Jay Hawkins before the movie?

ESZTER BALINT: I’m not sure I was familiar with it. Maybe. But putting that song in was 100% JIm, and building so much around it. He probably had the idea for the song even before the movie. He was very attached to it and Jim has very strong musical ideas for his films.

PHAWKER: I can see why. The movie featuring that song sort of reignited Screamin Jay’s career – or interest in him anyway.

ESZTER BALINT: I remember meeting Screaming Jay after that, he came to Squat Theater, and he was, indeed, a wild man.

PHAWKER: Did he see the film?

ESZTER BALINT: I believe he did. I remember him sitting in the living room telling crazy stories and being very sort of flamboyant.

PHAWKER: It’s a long time ago but you don’t remember any of these stories he told?

ESZTER BALINT: I do remember one story but I actually don’t love it because I think this was around the time that Marvin Gaye was shot and as I remember he was telling unsavory tales about Marvin Gaye’s family. He was in the know but it was a little too much disturbing info for me right when I was very upset about the death of Marvin Gaye. But there were other much better stories he told as well, I just can’t quite remember.

PHAWKER: So any recollections about making the film? It was made with almost no money right?

ESZTER BALINT: Which was difficult.

PHAWKER: Tell me about the crew, was there basically a guy holding the camera and a guy holding a light?

ESZTER BALINT: Well it was a stripped down, very lean crew of great people who went on to have pretty great careers. Tom DeCillo who was the cinematographer, and he did awesome work, he is one of the reasons I think the movie is what it is. But Jim has an amazing eye too and was an experienced cinematographer himself, so having Tom on board was his vision and he worked closely with Tom. The soundman Drew is someone who I think Jim has worked with many many times since. Sara Driver, Jim’s partner, was a producer and all around helper in every department imaginable. And Melody London was the editor. All very talented people.

PHAWKER: Are there any stories that would illustrate just how low budget it was. For instance, were you guys basically wearing your street clothes in the movie or were there costumes?

ESZTER BALINT: I think we maybe talked a little bit about costumes. But we were wearing our own clothes.

PHAWKER: The tone of the film, especially at the time, was very unusual. Very deadpan, a very spare, minimalist film and it owes a certain debt to French New Wave cinema – at least the look of things. I’m wondering, were all those things talked about or did you guys just find a sort of chemistry so that all of those things occurred naturally, or were they spoken about and rehearsed?

ESZTER BALINT: Absolutely the latter. Not talked about at all, to my recollection. Very natural organic situation.. I think that’s one of the things that makes the movie great – it was a vibe, not a stated agenda. Obviously Jim is influenced by that stuff you mention, so I’m sure was referencing it in some way, but it wasn’t discussed.

PHAWKER: You said you were good friends with John Lurie. He was kind of a dick in that movie and kind of not very nice to you, at least initially. As per the script. I’m wondering about that when you guys were bickering at each other and stuff like that and in between takes would you guys just be lighthearted or laughing or cracking jokes or did you stay in your characters even when the camera wasn’t rolling?

ESZTER BALINT: We got along. In fact he was the person I’d known the longest of everyone involved. He had hung out at Squat a lot, even pre -Lounge Lizards, and played there a bunch with the Lizards. So he was my oldest friend there.

PHAWKER: Did you guys maintain a friendship through the years or have you lost touch?

ESZTER BALINT: Very recently we’ve lost touch a bit sadly. I’ve known him so long… I will always think of him as a friend no matter where we are at.

PHAWKER: Did you happen to read that New Yorker story about his stalker?

ESZTER BALINT: Yes, I did.

PHAWKER: What is your take on that? It’s somewhat ambiguous as to where the truth actually lies in all that.

ESZTER BALINT: Yeah, isn’t that interesting. I have to be very careful talking about that. I will say that the stalker is a stalker. I feel like the whole piece might have been a big mistake. The way it was presented, giving the same amount of real estate to a disturbed someone who stalks people and hasnt’ really contributed anything significant to this world, in terms of his creations, and to John Lurie who has contributed a lot, regardless of any other details of the story, and who is not a stalker, regardless of any other character flaws he may have. It was a mistake to do the story in the first place, probably , and a mistake to present them as equals in this struggle I think.

PHAWKER:Let me just say that I think that he’s a fantastic painter. Out of all the art forms he has worked in — music and acting and painting — I think he’s a natural as a painter. I think he has to work a little harder at the other two.

ESZTER BALINT: I think he’s just one of those minds that will probably be really fantastic at anything he tries. For sure music and the painting because there he really gets to explore his talent without too much self-consciousness, tap into his greater powers, that special whimsy and humor and brilliance he has that’s even bigger than his need to be admired. He’s a great creative force. I love his paintings.

PHAWKER: So the film is a big hit, a big underground independent film hit. What was your experience of that moment of glory and what not? How did that change your life?

ESZTER BALINT: Wow that was a big moment and it was really educational. It kind of knocked me off my feet; I never experienced anything like that. We had a lot of glamorous people pass  through Squat Theater and all that, but it wasn’t on that level. Suddenly I was being recognized on the street. I was being asked for autographs when I was taking my laundry down to the nearest laundromat and things like that. I was 17 maybe 18. While it was a high, I don’t necessarily recommend that to anyone at that age. It’s tough because it’s going to feel great for a minute, and then you want more, it has an addictive quality, and then when the more does not come or doesn’t quite come in the same way you expect or imagine, it really is painful. And 18 is a bit young to process and sort that out. But it was great for me in the long run because that made me get down to business and figure out “What is it really that I want to do?” and take action that would deal with that sorrow and let-down. But it’s a really young age to experience that high and that low. It’s pretty hard.

through Squat Theater and all that, but it wasn’t on that level. Suddenly I was being recognized on the street. I was being asked for autographs when I was taking my laundry down to the nearest laundromat and things like that. I was 17 maybe 18. While it was a high, I don’t necessarily recommend that to anyone at that age. It’s tough because it’s going to feel great for a minute, and then you want more, it has an addictive quality, and then when the more does not come or doesn’t quite come in the same way you expect or imagine, it really is painful. And 18 is a bit young to process and sort that out. But it was great for me in the long run because that made me get down to business and figure out “What is it really that I want to do?” and take action that would deal with that sorrow and let-down. But it’s a really young age to experience that high and that low. It’s pretty hard.

PHAWKER: Did you want to continue on acting after that? Were there opportunities for that or did opportunities not come?

ESZTER BALINT: Yeah it was a mix. Just enough opportunities almost came to make me feel like, ‘Well, I’m about to be an adult, and I need to make money, this acting racket is a good way to do that, right?’ Guess what: I couldn’t really make money from it. Not enough to survive. It was very humbling. There weren’t enough opportunities. I also may have been a little bit of a snob I had come from a very –

PHAWKER: Bohemian background.

ESZTER BALINT: Yeah and I wasn’t about to beg for the next grade C sitcom that I could play the East European housekeeper in, just to pay the rent. Which maybe I should have and I’m not saying that was smart or wise of me, but again, I was very young, had an artistically priviiged background, but that’s where I was at, and so it was really hard.

PHAWKER: Those were the opportunities that were afforded to you though?

ESZTER BALINT: A few of those, yes, which was upsetting to me. And I didn’t really hustle that hard, and I may have turned my nose up at some things that did come my way and then also, the truth is not all that many things came my way. So it was a combination. Some things did happen, but not nearly as much as one would naturally expect after all that attention.

PHAWKER: And let me ask you what did you earn making that film?

ESZTER BALINT: I think a thousand dollars.

PHAWKER: For the whole thing?

ESZTER BALINT: Yep. I believe so and probably not up front . I think maybe nothing for the first part and then a thousand dollars when we did the rest. It was so long ago, can’t remember. But I have a small share of the film. There were some problems collecting on that for a while but in the end it worked out. Though I should say, I really never made much money on that film. Ever.

PHAWKER: You did participate in profit sharing?

ESZTER BALINT: I did but unfortunately somehow that didn’t actually translate into anything super substantial.

PHAWKER: Do you have any sort of relationship with Jim Jarmusch?

ESZTER BALINT: I do and we’re very friendly. I don’t see him that often but when I do it’s lovely.

PHAWKER: So any lingering resentment you might have about how things turned out financially or how things went down – this is not something that you blame Jim Jarmusch for.

ESZTER BALINT: You don’t let anything slide, you’re a real journalist. You’re good. If I wanted to go there I probably could, but I really don’t want to. I was mad at one point, and things weren’t run that well by the office, but they did made a very clear change on that at some point many years back now. I don’t know exactly what happened, and by the way I wasn’t an angel either, sometimes during the shoot I was a little snot, I remember well. As far as financial confusion especially during the early years after its release, I was not happy and there was some tension. But things got much more orderly later, and I’d really prefer to keep it in the “I don’t know” category applicable to a no longer relevant past. It was eons ago and I like Jim, we get along.

PHAWKER: You want to leave it that way

ESZTER BALINT: I want to leave it that way.

PHAWKER: That’s fine so let’s move forward. You are in a film called Bail Jumper.

ESZTER BALINT: Yep.

PHAWKER: I don’t know anything about this, tell me.

ESZTER BALINT: Well it never made any splash. It was another little indie and it was kind of an interesting project that was made for absolutely no money which seems to be most of the  projects that come my way. It was sort of a torturous process, making it, we had to continually stop shooting, while the fimmakers tried to collect more financing. So it dragged on for far too long and I think this intermittent way of making it may not have helped the momentum and the outcome. So it didn’t turn into not a spectacular film, but it had some cool ideas in it, and had some heart.

projects that come my way. It was sort of a torturous process, making it, we had to continually stop shooting, while the fimmakers tried to collect more financing. So it dragged on for far too long and I think this intermittent way of making it may not have helped the momentum and the outcome. So it didn’t turn into not a spectacular film, but it had some cool ideas in it, and had some heart.

PHAWKER: Bail Jumper came out seven years after Stranger Than Paradise. So in between what was going on? Were you continuing to do theater?

ESZTER BALINT: Yes, I did some theater. Well the theater company splintered, but under my father’s direction there were a few more plays we did, at The KItchen, The Kennedy Center, at BAM, among quite a few other places and out of the country as well, after we left the original 23rd stree locations. Which by the way was fairly traumatic for me, it was sort of the “divorce” that I never quite got over, ha. So I did quite a bit of work, having even bigger roles in the later plays, working as musical director as well, being more involved creatively and we did a bit of traveling. I also did a Miami Vice episode. And I was in Chantal Akerman film as well. Something about her passing hit me very hard. She was cool!

PHAWKER: What? You were you in the Miami Vice episode? Were you a Hungarian housekeeper? Were you the exotic Eastern European Other.

ESZTER BALINT: No I wasn’t, thankfully. I was a mother, with I think a kidnapped baby. But I do remember making that was a weird experience, I felt extremely out of place in Miami and I didn’t connect with nearly any of the other actors. It was a lonely experience.

PHAWKER: Speaking of Florida, I meant to ask you this about Stranger Than Paradise – did you guys shoot everything in New York or did you actually go to Florida or to Cleveland?

ESZTER BALINT: Absolutely yeah when you were asking about examples of the difficulty of shooting on a shoestring budget definitely the first thing that popped in my mind was the Cleveland scene by the lake. It was frigid in a way I’ve never experienced before or since, and probably on any real budget you’d have the chance to escape to a warmed up car at least between takes, or some other place. That didn’t happen. It was brutal. I think I was probably very unpleasant on the shoot at that point – but the scene is clearly one of the highlights of the film.

PHAWKER: You mean the scene where the three of you check out Lake Erie, but it’s all whited out with snow, all you can see is this big white nothing. Is that what you’re referring to?

ESZTER BALINT: Yes.

PHAWKER: Which is funny because so much of the film is about the characters confronting the Big Nothing of post-modern living. So then you were in a film called The Linguini Incident which I also don’t know anything about that. Tell me about that.

ESZTER BALINT: That’s okay. Not that much to know. That was a year or two after Bail Jumper. In fact I think it was a screening of Bail Jumper that brought me out to live in LA. I was actually nominated for an Independent Spirit award for that movie.

PHAWKER: Congratulations. So you moved to Los Angeles for a time?

ESZTER BALINT: Yes I lived in LA for seven years and that’s when I ended up doing The Linguini Incident.

PHAWKER: Why are you sort of wincing about The Linguini Incident?

ESZTER BALINT: I think I wince about everything I’ve done. But I think that one might be pretty silly, or maybe I’m just not thrilled about the job I did myself. But one very cool thing was I got to meet David Bowie and work with him.

PHAWKER: Is he in it?

ESZTER BALINT: Yes.

PHAWKER: Tell me about that. I love David Bowie.

ESZTER BALINT: He would probably not remember me now. But we actually worked together pretty closely because we had some scenes together and on movies there’s a lot of down time. And I loved him. He was smart, fun, a great hang. I was so happy to get to know him a little. And I should say all the people involved in that film were great. I have only fond memories of the director, writer, producers, and all the actors and the crew involved.

PHAWKER: Were you a David Bowie fan?

ESZTER BALINT: I was. And he was just a huge influential presence in my life, growing up. I had seen David Bowie Ziggy Stardust period posters at my dad’s friends’ houses. And around 13 or so, I was a rabid fan of Lodger when it came out. Which I should say means I had good taste early. That’s still a great record. So yeah, meeting him knocked me off my feet, it was hard to keep my cool at first – though I was always pretty good at that. But he was easygoing, breeze to get along with, in my experience.

PHAWKER: And then you were in Shadows and Fog, which is a cool Woody Allen movie that I don’t remember much about because I saw it in the theater when it came out but tell me about that experience. How did that come about?

ESZTER BALINT: It was one of those traditional audition scenarios. I was called in to audition or to meet Woody Allen. Which consisted of me waiting for him in the lobby of a dark hotel uptown, and him coming in with his casting director and shaking my hand and saying “hello, nice to meet you” and me getting a call from my manager hours later saying he absolutely loved me.

PHAWKER: You didn’t even do a scene or read the script?

ESZTER BALINT: Oh no, he doesn’t let anyone read the script he’s very secretive about that.

PHAWKER: So he just wanted to meet you and size you up and say ‘Yeah she’s right for the role’?

ESZTER BALINT: Yeah but it wasn’t even like, ‘How are you? Tell me a little about yourself’ – nothing like that. It was ‘Hi, nice to meet you. Okay bye bye.’ It was the easiest quickest good impression I had ever made on anyone. I did one scene with Mia Farrow and I think John Malkovich, but didn’t really have much interaction with anyone on the set.

PHAWKER: And then you also had a role in Trees Lounge tell me how that came about. Were you friends with Steve Buscemi?

ESZTER BALINT: I was. I knew him from the early ‘80s performance days In New York and he knew about Squat Theater. I think he had seen shows there and we were friends later. And he had me in mind for something in that script I think for a while. Have you seen the movie?

PHAWKER: Yes, but again I saw it in the theater when it came out and I haven’t seen it since I don’t remember that much about it. He’s driving an ice cream truck around and getting stoned with teenage girls is that right?

ESZTER BALINT: Yeah that’s correct.

PHAWKER: Are you one of them?

ESZTER BALINT: No, I’m the wife of this construction guy that he becomes friendly with but things go south. I actually caught it recently on cable, totally by accident. It stands up really well, today. That movie is dear to my heart, I think it is great. There’s something about the dialogue, and the characters that I love.

PHAWKER: And then in ‘99 you made your first album, Flicker. Tell me about that. I was only able to dig up one track on Youtube. I like the track I heard, it sounded a bit more electronic than the two albums that came after which sound a little bit more organic rock.

ESZTER BALINT: I would probably say that’s true. So the writing of that record came about during the time I was living in LA and actually I traveled back to New York to shoot Trees Lounge but I was still living in LA. I had at that point decided that the whole acting thing wasn’t for me anymore. It just was too toxic living in LA. My mood just soured on that as a way of life.

PHAWKER: Well being an actor is like 99% rejection right?

ESZTER BALINT: Yeah the rejection, the lack of control and also just the quality of the material and the quality of the people and the goals everyone pursues. There is somethign that I found toxic for me about it. It’s also a very lonely town. It just became apparent that it wasn’t my world and I need to do something else. The music thing happened very organically for me because I’d been dabbling with music my whole life one way or another almost continuously. I studied classical violin when I was a kid, then I DJ’d, then I was a music director for many of the Squat plays and sang in some of them, then I studied classical singing for a while. It was a really good time for music, it was the ‘90s I was living in a LA there were a lot of good bands and songs on the radio, and I was friends with many musicians: I felt inspired. I started working with this guitarist out there, Pascal Humbert, it sort of clicked that this is what I need to do. Music was something I’ve always done very very privately but I was ready to make it more of a career. Flicker came out of that transition.

PHAWKER: What I heard reminded me of — do you remember that group Soul Coughing?

ESZTER BALINT: Yes, sure, and I worked with one of the member of Soul Coughing for a long time.

PHAWKER: Which one?

ESZTER BALINT: Sebastian Steinberg. He played with me for a few years, we even toured together.

PHAWKER: Somewhere in there you play on an Angels Of Light album?

ESZTER BALINT: Around the time I made my second album, Mud, Michael Gira called to ask me to play on Everything Is Good Here, Please Come Home.

PHAWKER: What are you doing on that? Singing or playing violin?

ESZTER BALINT: Playing violin.

PHAWKER: And you played on more than one?

ESZTER BALINT: Yeah then he called me back for another Angels of Light record, We Are Him, which I love. Actually I love both of them but that one is really great. “

PHAWKER: Backing up to Flicker, what happened with Flicker?

ESZTER BALINT: It was critically well received but it was a small little indie record. I didn’t have any sort of touring money behind me so it was tricky. But I did a little touring in France.. One cut from the album was in the film “Lovely and Amazing.”Having come from the acting world, in the public eye, , I felt the burden to prove that I was doing this music thing for real, it wasn’t a vanity project, and on that front I had very good reception.

PHAWKER: And somewhere along the way you connected with Marc Ribot?

ESZTER BALINT: I actually knew Marc for a long time. He was somewhat on the scene too , and he was the guitar player in one of the versions of the Lounge Lizards.

PHAWKER: Well, I love him and you played with him on a Cubanos Postizos record, which I love. You were later a member of Ceramic Dog?

ESZTER BALINT: Yeah I was a guest member of his band Ceramic Dog for about a year, back in 2010. Also Marc and I did a track together for a Serge Gainsbourg tribute album called Great Jewish Music: Serge Gainsbourg. It was released on John Zorn’s label, Tzadik Records.

PHAWKER: Is John Zorn a friend as well?

ESZTER BALINT: Well I know John but we don’t hang out. I don’t see him around. But we have that history of being from that same tribe, in the early days, so in that sense sure, I think of us  as friends.

as friends.

PHAWKER: Both Mud and Flicker were produced by J.D. Foster. He’s not on my radar. What’s his story?

ESZTER BALINT: He’s a bass player, he’s played with a lot of people including Dwight Yoakam for a time, but he’s also a producer, and he actually produced the Cubanos Postizos records that you like and he’s produced a couple of other things for Marc, and he’s also produced some other lovely records. I went to him to do Flicker because we met while I was shooting Trees Lounge (he was married to Lisa Rinzler the cinematographer) and he’d done a record I really liked that I was listening to a lot at the time I was writing Flicker. It was this record by Richard Buckner called Devotion and Doubt,. He also produced a few other Buckner records.

PHAWKER: And what happened with Mud? How was it received?

ESZTER BALINT: So with MudI had this label, Bar None, with me and I think I actually got a little more press with Mud. Everything seemed a bit more organized. . It was again modest but well received. I had a wonderful interview on NPR, and there’s a really good reviews in some magazines which seem to no longer seem to review smaller records like mine. (Paste comes to mind, but quite a few things along that line) But it was nothing immense. It got good reviews and that NPR interview was fantastic but I think this was right on the eve of the big change. So I think the reason I’m saying that and why it’s significant is because in another time that it of press, NPR play, etc, would have translated in a different way for me. I think things started shifting in a huge way just around that time, in the record industry, with the whole digital craziness so none of that really translated into that much on the ground level.

PHAWKER: You mean downloading and people not buying albums anymore?

ESZTER BALINT: Yeah. I feel like when Mud came out it definitely took a hit from the beginning of that change which was kicking in big time then.

PHAWKER: So then what happened between Mud and now?

ESZTER BALINT: Well a lot of life and not that much making records. But I had a child

PHAWKER: Congratulations!

ESZTER BALINT: Thank you. Actually my child was born just before Mud came out but the first year is like a piece of cake compared to what comes after. Then I also dealt with a lot of personal things. My father was sick. It was a sort of prolonged long distance situation so that was very difficult to navigate. Simultaneous I was raising a young child so it was somewhat consuming; I was a very hands on mother, with him a lot. Anyway a lot of other personal things I won’t get into now but mainly child rearing. But I did do those couple of Angels records, and a Swans record and worked with Ceramic Dog and did some local NY gigs between those two records – and did all the writing for Airless Midnight as well. So it wasn’t an artistically completely dry period by any stretch.

PHAWKER: The first Swans record, after he reactivated the band, The Seer?

ESZTER BALINT: Yep, The Seer.

PHAWKER: Which is a great record.

ESZTER BALINT: Yeah, I’m very very proud to be included on that.

PHAWKER: Now Michael Gira has a reputation of being a pretty stern taskmaster.

ESZTER BALINT: I’ve not worked super closely with Michael so I haven’t been on tour with him or anything like that, but I’ve only had good experiences with him, and I’ve recorded I think four different times with him, including a project he called me in on which he produced.

PHAWKER: He didn’t yell at you? Hurt your feelings?

ESZTER BALINT: Never. He’s been extraordinarily polite, gracious, very thankful. Now it’s been in small spurts but we’ve worked together.

PHAWKER: OK, because if he was mean to you then Michael Gira and I were gonna have problems, and I was gonna have to go straighten shit out.

ESZTER BALINT: Very nice of you to say.

PHAWKER: I would beat him up for you, Eszter. You say the words and I’ll beat him up,

ESZTER BALINT: I have heard he has a reputation but honestly no need to beat him up on my account. I’ve not experienced any of that. He’s always been fantastic with me.

PHAWKER: So now are you living in New York this whole time?

ESZTER BALINT: Yeah so I moved back – we skipped over that part but I lived in LA seven years, hated it by the end, despised  it, the day I drove back to New York I can pretty much unequivocally say was the happiest day of my entire life. And that was in ‘97 and I’ve lived here since.

it, the day I drove back to New York I can pretty much unequivocally say was the happiest day of my entire life. And that was in ‘97 and I’ve lived here since.

PHAWKER: So what have you been doing for income? How have you managed to live in New York?

ESZTER BALINT: It’s really hard. I have a kind of flukey housing situation which I’m hanging on to by a thread. It’s always a little bit of a source of stress

PHAWKER: Is it a rent-controlled place?

ESZTER BALINT: It’s a very long boring story, but it’s a good arrangement in that it’s affordable, but it’s bad in that it’s stressful and hanging on by a thread. I do little things like collect ASCAP money, I have done some teaching of music, I got paid for Louie, a few other small acting gigs since, I made some money touring with Ceramic Dog, etc. and I’m continually figuring out the money things. I’ve had a lot of non glamourous jobs through the years too. Oh wait we didn’t talk about that – do you know that I did Louie?

PHAWKER: Oh I know about that. I love Louie. The minute you came onscreen I turned to my girlfriend and said, ‘I think that’s the woman from Stranger Than Paradise!’

ESZTER BALINT: Good! Good call!

PHAWKER: And then I was like that is the woman from Stranger Than Paradise, and this is some sort of a homage to it, I think.

ESZTER BALINT: Well I don’t know if it’s an out and out tribute but –

PHAWKER: Well not a tribute but Louis knew that movie.

ESZTER BALINT: It’s a nod. I think by casting me and making my character Hungarian it’s probably a bit of a nod. But that is just conjecture..

PHAWKER: Because he saw that film, he knows that film right?

ESZTER BALINT: I’m very sure he does. We never discussed it.

PHAWKER: You never talked about it?

ESZTER BALINT: Not really.

PHAWKER: Let’s talk about the Louie thing.. How did that come about? You were great in that, by the way.

ESZTER BALINT: Oh, thank you very much. I enjoyed doing it and I hadn’t done any acting for a long time. I mean since I sort of officially divorced my acting career in Los Angeles, I pretty much haven’t done any acting.

PHAWKER: So how did he find you then?

ESZTER BALINT: Louis was a parent at the same school where I was a parent. We had some mutual friends. And like you suspect, I suspect he knew me from Stranger Than Paradise.

PHAWKER: But he never said anything to you about it? He wasn’t like ‘I loved you in Stranger Than Paradise’ or ‘I love that movie.’

ESZTER BALINT: No. He said hello to me and knew I did music. He came to see me at my gig too. He came to see a show of mine.

PHAWKER: Of you playing music?

ESZTER BALINT: Yeah. He made some quick reference to the movie I think at some point in our conversation. but we didn’t really get into that. I didn’t want to put him on the spot like ‘Hey is this a nod to the film or are you just casting me because of that?’ At the end of the day that was an unnecessary conversation to have, and I thought it might put things in my head that I didn’t need in my head right before going in to do that job.

PHAWKER: And you got to work with Ellen Burstyn who is amazing.

ESZTER BALINT: Yeah she’s fantastic, really a delight working with her.

PHAWKER: Please tell me she’s a nice person.

ESZTER BALINT: Very.

PHAWKER: Because I would beat her up, too, if she was mean to you, Eszter. Ordinarily, I would never hit a woman. There are no limits to where I would go for you.

ESZTER BALINT: [laughs]

PHAWKER: Did Louis ask you personally to take the part?

ESZTER BALINT: Yes he did. So I already knew him a bit but he came to a gig and then he approached me after, said that he’d been writing this part and wants me to read for it. No that’s not the word he used I think he said he had me in mind for it and that would I read it, and meet with him and then we went from there.

PHAWKER: You were in six episodes all together. How long did that take to film?

ESZTER BALINT: I think we worked on it for two or three weeks. I think I had like twelve days of shooting and it wasn’t all continuous because there was a Thanksgiving break.

PHAWKER: Six episodes were shot in twelve days?

ESZTER BALINT: They’re very efficient. It’s a low budget production. To be clear, my scenes were shot in twelve days, not all six episodes were shot in twelve days.

PHAWKER: Now Louis is the director? He’s the showrunner?

ESZTER BALINT: Everything.

PHAWKER: So he’s standing outside and giving directions to everyone and explaining things, he says roll and just walks into the camera shot and you guys start acting, is that how it goes?

ESZTER BALINT: Yeah, then he says ‘cut’ and and he looks at the footage right after. He’s also incredibly knowledgeable about cinematography, so he’s super involved in the shooting and lenses used and all that. I think he used to shoot his own little films, so yeah he does everything. He writes of course,, and he edits too. But as far as giving directions, he’s very intuitive, so there wasn’t actually a ton of directorial instruction going on.

PHAWKER: You speak in Hungarian the whole time. Somewhere I saw somewhere on the internet they translated what you were actually saying.

ESZTER BALINT: Yeah which I never talked to him about but I bet he wasn’t that pleased about that.

PHAWKER: Why is that?

ESZTER BALINT: Because it wasn’t the point. The whole point was that you the viewer –

PHAWKER: Doesn’t know what you’re saying.

ESZTER BALINT: RIght. I think that’s what he was going for. But it’s a minor issue.

PHAWKER: Did you do the translating for what is said?

ESZTER BALINT: Well it would be sort of an ad lib situation based on ideas he sketched out in the script. I’m trying to remember but in the script a lot of times it was left blank because the point was he didn’t understand what’s going on and sometimes he would put in little signifiers as to what she might be saying but the dialogue was never written out in English because the point was you don’t understand. So there was a lot of ad lib on my part just taking the situation and going with it. So if I were him I would have been a little frustrated by that whole translation business.. but whatever, you can’t get away from that this day in age.

PHAWKER: That had been a long time since you had acted, was it easy to transition back into that or did you have to build your acting muscles back up?

ESZTER BALINT: Yeah I was really nervous about the acting muscles. At first I almost wanted to talk him out of hiring me. I remember telling him, ‘I don’t know if you realize but I haven’t done this in a long time,’ and I told him to take his time and think about it and he said ‘You know I’m feeling pretty good about this and I usually just go with my instincts.’ I had recently, coincidentally, just felt a tiny itch to try acting again, so the timing was very right; I think that’s what got me through honestly, the desire to do it. And I’d been performing a lot on stages over the years, doing my music so there’s something about that muscle which connects to the acting  muscle. We are telling stories in songs as singer/performers, which relates to the task of an actor. I think I tapped into that performance experience and it helped me reconnect with acting. It felt good to flex that muscle again.

muscle. We are telling stories in songs as singer/performers, which relates to the task of an actor. I think I tapped into that performance experience and it helped me reconnect with acting. It felt good to flex that muscle again.

PHAWKER: And so when did you actually see the finished product? When it was actually on TV?

ESZTER BALINT: Yeah.

PHAWKER: And? Was it hard to watch?

ESZTER BALINT: Really hard.

PHAWKER: I’m a recovering musician and I know it’s hard to listen to your own album, all you can hear is the mistakes or things you wish you’d done differently. Are you super self-critical?

ESZTER BALINT: I tend to be super self-critical and yeah for me to listen back to recordings, it’s really tough. Watching myself on TV was surreal because it was out there for the world to see but I was alone watching it on this box, and I had no idea how it was coming across. No sense of feedback at all at first just my own completely subjective sense. It wasn’t anything like performing in a room live in front of an audience where you can kind of gauge the temperature a bit. It was pretty horrifying and upsetting to tell you the truth, at first.

PHAWKER: Really? Upsetting?

ESZTER BALINT: For a minute yes. Because I hadn’t done this in a long time, and I felt extremely vulnerable and exposed. And then that minute passed and I realized that it was okay, I started getting the sense that it read okay, it read pretty well. The responses started coming in and it seemed like things were fine. So I felt like: ‘Calm down, breathe, it’s alright you will live another day.’

PHAWKER: And would you consider taking any other roles if they came your way if you liked the material?

ESZTER BALINT: Absolutely I really got into it and actually did do a couple acting things after that . but I don’t want to talk about that because they’re minor roles and you never know what’s going to happen with those projects or my part.

PHAWKER: Are they films?

ESZTER BALINT: Yeah they’re, indie film projects.

PHAWKER: Is there anybody involved in these projects that I would know or would have heard of?

ESZTER BALINT: Might be but right now I want to keep it under wraps because like I said you never know what’s going happen with the project or if you end up on the cutting room floor. But to answer your question, I would definitely be into it now.

PHAWKER: You’re not talking about Star Wars, are you? You’re not in Star Wars are you?!?

ESZTER BALINT: Yeah I’m gonna do like a Beyonce, I’m gonna drop it as a surprise, no pre-publicity.

PHAWKER: That’s the way to go, put it all up on social media.

ESZTER BALINT: It seems to work for her.

PHAWKER: So let’s talk about the new album which I like a lot. That’s why we’re talking today.

ESZTER BALINT: Oh thank you. What kind of musician are you by the way? Can I ask you?

PHAWKER: I’m a retired rock star. I was a rock star in my own mind, largely.

ESZTER BALINT: I love that. Retired rock star.

PHAWKER: Semi-retired I call myself because I could still go back in the game. I’m kind of like Jay-Z, I might come back. I said I was retired. I was in a band in the 90s that was signed to Capitol Records during the sort of the height of the Nirvana era. I suppose we sounded a little like them.

ESZTER BALINT: Which band?

PHAWKER: We were called the Psyclone Rangers. You can look us up on All Music Guide where there’s an entry there. We kind of had a very similar experience to your career. We had some nice press. We got to tour a lot which I really love – traveling across the US with your buddies, kind of like your pirates, and at the end of every day you get to the place you’re going to and there’s a free case of beer waiting for you. Pretty awesome.

ESZTER BALINT: Yeah it’s pretty awesome. A lot people have a hard time letting go of that life.

PHAWKER: Now i’m happy to be a writer. Rock ‘n’ Roll is a young man’s game. To answer your question I was a singer.

ESZTER BALINT: You were a singer, okay.

PHAWKER: By singing I mean more in the Lou Reed sense of the word and less in the Pavarotti sense of the word.

ESZTER BALINT: Okay well that’s great. Did you ever hear Lou and Pavarotti sing together?

PHAWKER: I did not did they do one?

ESZTER BALINT: You have to check that out.

PHAWKER: That’s a weird combo. That’s weird that I pulled those two I thought I was bringing up two completely unconnected things that’s weird.

ESZTER BALINT: Perfect Day.

PHAWKER: Just to wrap up with the Louie thing, Louis is a nice guy right?

ESZTER BALINT: Louis is a nice guy yeah.

PHAWKER: No need for me to get physical.

ESZTER BALINT: You’re looking for the angle to bash everybody! No need to go beat him up, no no no but i’ll think of someone for you to go beat up now that you’ve volunteered.

PHAWKER: I’ll be your muscle. But don’t pick anyone too big or too tough. I don’t want to get my ass kicked in the process.

ESZTER BALINT: I’ll go easy on you. Maybe it’ll be a girl.

PHAWKER: A girl or Woody Allen. I’m pretty sure I could take Woody Allen .

ESZTER BALINT: Well the press has been kicking him enough.

PHAWKER: Yes they have. Let me ask you about that since you had an experience with him. How do you process all of that controversy? I know that it was a very small role and a long time ago but you are part of the Woody Allen legacy or Woody Allen’s legacy like it or not. What do you make of all that?

ESZTER BALINT: Oh it’s so complex. I mean first of all that controversy wasn’t out it didn’t really exist when I did it, so I didn’t concern myself with that then but if you’re asking how I would approach it now… yikes. Can I have like a lifetime to think about it and give you the right answer?

PHAWKER: In a larger context and just Woody Allen can you separate the artist from the art? Could you appreciate Hitler’s paintings separate from his crimes against humanity?

ESZTER BALINT: Well he was an awful painter.

PHAWKER: Maybe not a good example.

ESZTER BALINT: And no I don’t think you can go that far but I think there is humanity in nearly everyone, and I think a lot of very neurotic troubled people, who go astray in life- art is maybe where they shine because it’s therapeutic in a way, and real life is not necessarily where they shine. So one side of this coin is that some of the people who behave terribly in real life, would behave even worse, if they didn’t do their art. I do believe it’s in part an attempt at working troubling things out, and it may bring out their best selves. But I think there is a point where it is appropriate to take some sort of stand, and not support someone financially or with publicity and accolades who is doing great harm to others. So I’m uneasy joining the camp of ‘that’s just his personal life leave that out of it. and I’m also uneasy in certain cases to jump in the camp of completely vilifying someone’s work and boycotting it because of some of real life misdeeds, especially when we are not 100% sure of what went down. I think if the admiration of the work becomes a collective whitewashing of any real life wrongdoing, that is problematic for me. It really depends on the case. But I do think it’s too complex an issue and too long of a conversation. I do feel as a woman that there is a lot more permission in the world for public male figures to do impermissible things in private and still be glorified for other things, having their deeds swept under the carpet, than it is for a woman. This inequality is real, and not so cool I think.

PHAWKER: Good answer very diplomatic.

ESZTER BALINT: Is it?

PHAWKER: I think so. So moving on to your new album, you crowdfunded the recording, correct?

ESZTER BALINT: Yes, through Pledge Music which is similar to Kickstarter but it’s geared strictly towards music and is a slightly different format.

PHAWKER: And you raised the necessary money I think and then some right?

ESZTER BALINT: Well yes that’s a little bit of can of worms because one of the problems with these fundraiser things is that they often steer you to set up a very modest goal because they want you to meet your goal. And you want to meet your goal. But to the outside world it looks like, “oh you met your goal and then some.” when in reality you’re still barely able to eek out a record from the money you actually raised.

PHAWKER: What was your goal? $5000?

ESZTER BALINT: Suprisingly I only aimed for $7000 which hardly covered the cost of Airless Midnight. I ended up raising about $13,000 total. Pledge takes a cut, PayPal takes a cut. I also had to hire a publicist  and have some other costs involved in the post-release that that money doesn’t really cover. But I’m not complaining. It’s the way to go. I had no other choice really, and so I’m immensely grateful for the money I was able to raise and for the wonderful people who pledged. But it was mixed experience. Not easy. There are a lot of hours that end up being devoted to fundraising and promoting, and I don’t know if i can do that again. That’s wearing too many hats for an artist. For me that aspect of it was too difficult. If I do this fundraising thing again I’ll have to have someone helping me and take over that part because it was too much; posting updates, promoting my product and asking for funds while trying to finish writing songs and gathering musicians and booking studio time and thinking about the overall mood of the album.

and have some other costs involved in the post-release that that money doesn’t really cover. But I’m not complaining. It’s the way to go. I had no other choice really, and so I’m immensely grateful for the money I was able to raise and for the wonderful people who pledged. But it was mixed experience. Not easy. There are a lot of hours that end up being devoted to fundraising and promoting, and I don’t know if i can do that again. That’s wearing too many hats for an artist. For me that aspect of it was too difficult. If I do this fundraising thing again I’ll have to have someone helping me and take over that part because it was too much; posting updates, promoting my product and asking for funds while trying to finish writing songs and gathering musicians and booking studio time and thinking about the overall mood of the album.

PHAWKER: How do you write songs?

ESZTER BALINT: I work with words first usually. Sometimes I get inspired by listening to a groove in my head and like the feel of the sounds of certain words on that groove so I’ll build around that.. But I’d say at leastt 80% of the time it is really just pen to paper, much like a poem or short story. It’s words first.

PHAWKER: For most songwriters the words are sort of an afterthought. The melody comes first with the chord changes. Do you play other instruments other than the violin?

ESZTER BALINT: Yeah I play the guitar and I write mostly on tthat. I don’t really consider myself a guitar player but I just play rudimentary guitar and weird little licks my own way. But I write on that instrument more than any other.

PHAWKER: And how long were you writing these songs? Do some of these songs go back a long time ago?

ESZTER BALINT: Yeah some of them started germinating when my son was pretty small. Soon after Mud I’d say. Some were more recent.. It’s such a nonlinear process. I rarely just down on Monday and start to write a song and then Wednesday it’s finished and I move on to the next song. It’s not like that for me. Maybe for other songwriters it is.

PHAWKER: Do you want to go through this track by track I’ll just throw out the title and you can tell me whatever comes to mind if there’s some story behind what inspired it or some story about making it or whatever you want to say. Do you want to do that?

ESZTER BALINT: Well let’s try it if I have anything interesting to say.

PHAWKER: If you’re boring we’ll edit it out but you haven’t been boring so far you’ve been pretty interesting so far.

ESZTER BALINT: Oh good thank you.

PHAWKER: First of all it’s called Airless Midnight, why?

ESZTER BALINT: I have no idea why. All I know is i’ve never struggled this much with an album title befor. I had everything ready to go but couldn’t sign off on the title and felt very stuck. Finally I started narrowing in on something to do with night and air and looked at different phrases from different songs and then let it rest because the harer I tried to pin it down the less it came – which is a very interesting phenomenon in writing or creating in general. was almost I would say getting into a funk about it, searching for the title became an obsession, just killing my joy. So I put it aside. Then in a totally subconscious way this phrase just came to me , I have no idea from where, but I woke up with it on my mind and lips. It felt so familiar that thought I had read it somewhere or heard it somewhere so I quickly googled it to see where I was plagiarizing it from. I was relieved not to see it anywhere and thought, that sounds good. That has a good ring to it.

PHAWKER: It’s evocative of noir I think. Do you think that’s a fair characterization of your music or your sensibility as a creative artist that there’s a noirish sensibility to it?

ESZTER BALINT: You know what, it’s interesting that word has popped up quite a bit. Yeah I don’t think I set that out as an agenda but actually I’d be interested to flip the question a little bit. Why? Because a lot of people have used that word not just you. I’m not the one listening to this stuff objectively. Why does it sounds noirish?

PHAWKER: I don’t know just everything – what I’ve seen of your work as an actress and what I’ve seen and what I’ve listened to of your music, it all sounds like things that would happen after midnight. It all sounds like things that are in the realm of light and shadows and nocturnal things when the whole world is quiet and you are solitary.

ESZTER BALINT: Yes, good. All that resonates. Again none of this is ever planned and I think it would be really bad if it were. but definitely when you say those things it resonates as authentic to to where I live creatively.

PHAWKER: I’m guessing, are you a night person? Do you stay up late?

ESZTER BALINT: Forever struggling to turn myself into an early morning person.

PHAWKER: I am just like you. I don’t think it’s gonna happen. I’m your age.

ESZTER BALINT: Have you already given up? Because I’m still not giving up but its not working.

PHAWKER: Well having said that I do love the mornings though. I love the light in the morning it just seems like anything’s possible in the morning.

ESZTER BALINT: Like really early morning is nice and people always say you get a lot of creative work done in the really early hours. Not to mention I have a son who goes to school. So it would be good for me to turn into a really early morning person. But it’s an eternal struggle.

PHAWKER: Well that would make sense then that noir thing that we’re talking about that after midnight vibe.

ESZTER BALINT: I read a lot of Raymond Chandler when I was young.

PHAWKER: So we’re going to talk about your album and kind of go song by song . I just listened to it very closely and enjoyed it quite a bit.

ESZTER BALINT: Oh good i’m glad.

PHAWKER: I think the lyrics are really good. I think you are a poet. I don’t say that lightly.

ESZTER BALINT: I really appreciate that, as I work pretty hard on my lyrics.

PHAWKER: The first song is “The Mother,” which was inspired by that news report that you read about the Beslan school siege right in Russia.

ESZTER BALINT: Yes. But it’s important to me that people hear the record before reading my own intentions with the lyrics, because they can have their own stories about the songs which are just as valuable. They are entitled and encouraged to relating to the words in their own way.

PHAWKER: I like the line, ‘violence, the color of her hair’ does that mean she’s a redhead?

ESZTER BALINT: I actually pictured it as black – it’s up to interpretation.

PHAWKER: Black could be the color of violence too right.

ESZTER BALINT: It’s a specific hue.

PHAWKER: This line about threatening to pull the eyes out of the head of the person responsible is that actually a quote from the story is that from one of the mothers said something like that?

ESZTER BALINT: Yes that is a quote, and I would say that’s the line that – well i mean the whole story had me in fetal position pretty much for a week – but that line, there’s something so visceral and the contagiousness of violence but also being able to understand that violence. Yes that’s a direct quote from the NY Times article on that incident. And I wanted to write the words like reportage but also have some poetry in it.

PHAWKER: Do you think that you could connect to that sentiment if you weren’t a mother?

ESZTER BALINT: I think so.

PHAWKER: “Let’s Tonight It,” I like the wordplay of using tonight as a verb which it’s not technically speaking. It kind of has its sort of you know ‘Come on baby let’s get lost’ Chet Baker kind of vibe lyrically speaking but it’s an invitation to this seemingly seductive but probably illicit romance.

ESZTER BALINT: Yes there’s definitely that layer to it but I think I wanted to leave that a little ambiguous. But the thing that is strong there is throwing caution to the wind kind of energy and going with that force of the moment and not taking that pause and there are going to be consequences. But it’s not coming from a preachy point of view, it’s more exploring that idea. This is where it can get a little stupid trying to explain lyrics.

PHAWKER: Which is generally associated with younger people. I think you and I are roughly the same age, do you still feel that you can keep to impetuousness and whim and just follow the moment?

ESZTER BALINT: I don’t know if it was necessarily strictly autobiographical but I think we all have that tendency, the potential in us, whether we act on it or not.

PHAWKER: Are the songs strictly autobiographical or strictly personal or somewhere in between? Is there a clean line between the two is is a mixture do they go back and forth?

ESZTER BALINT: A mixture. There’s more and more in my writing lately where I get inside other stories and other characters, but try to do it in a very empathic way, putting myself in their shoes. Then vice versa if I”m exploring something that is a little more directly autobiographical, I deliberately try to detach a little bit from my own personal subjective “feelings’ and write it in a sort of reportage style. . So I definitely don’t think they are diaristic type of writings.

PHAWKER: I really like your singing. Did you tell me did you take lessons or are you self taught or did you have any formal schooling?

ESZTER BALINT: I do have some formal schooling. For a little while, ages ago I was studying to be a classical singer but a lot of that actually got in my way initially when I started doing this songwriting things. So I had to sort of unlearn that but I feel like I’ve kind of crossed that bridge. I really can’t stand my singing in earlier recordings and I know this is what I struggled with.

PHAWKER: I’m curious about that explain to me how does that sort of formal training get in the way of you expressing yourself and is that like akin to say a formally trained painter who basically paints in a primitive way?

ESZTER BALINT: It’s not that I think formal training is the enemy of singing well. I was referring specifically to classical singing and that it is a misconception that it needs to be the basis of all other singing.

PHAWKER: What’s the difference between a classical singing and I don’t know how would you characterize what you do?

ESZTER BALINT: Well do you listen to much classical singing? I’m not trying to be cheeky.

PHAWKER: I’m not sure what you mean.

ESZTER BALINT: Like opera.

PHAWKER: Almost none.

ESZTER BALINT: Well it’s a very different style. There are certain things in that school of singing that are great foundational principles that got passed down, which can still be valuable for modern singers, a few of the great principles of bel canto style singing for example. But there’s a lot of other crap that also gets passed down to singers as the be all end all, which is not at all applicable to a more conversational intimate soulful style of singing. So at first I found that transition really hard. Also when you take all the technical challenge aspects and focus away, which is built into classical training, singing feels a lot more raw and vulnerable and scary . So at first it was like “Whoa, feeling a little naked here.”

PHAWKER: In classical singing there’s a lot more vibrato?

ESZTER BALINT: Yeah they use more vibrato. And the agenda is different. The primary focus originally was on booming over an orchestra, acoustically so you can be heard. So there’s a lot about volume which doesn’t really apply once you bring in amplification – and you can get a lot more intimate.

PHAWKER: Before amplification.

ESZTER BALINT: Before amplification correct. So therefore it has to employ a different technique for that agenda and that agenda doesn’t apply. Thankfully I’ve had lessons with some very smart professors who know this and are debunking that myth that classical singing is good for all singing.

PHAWKER: Okay “Departure Song” sounds to me like a person leaving a long distance lover that he or she has visited, driving to the airport, getting on the plane.

ESZTER BALINT: Well actually it wasn’t a lover but it’s so interesting where people’s minds go.

PHAWKER: Well I heard it as you go to visit this person and this is your thought that you’re leaving to return back home but I’m guessing if it’s not a lover it’s a loved one right?

ESZTER BALINT: It’s definitely a loved one yes.

PHAWKER: And you already told me that a lot of these songs are inspired by your father’s passing and the later years of your life and your relationship with him so I’m assuming that was sort of the basis for this, the emotional framework.

ESZTER BALINT: Yes, but there’s a little extra bite. It’s not just another departure song about leaving someone to go to some other far away place. to a far away place. It is also about leaving somebody who you will never see again – because in this case they were sick and dying. Stepping on that plane and flying away and the finality of leaving that person, who is still alive but fading. There’s no return.

PHAWKER: And this is drawn from a personal experience. There was a point where you knew you were going back home and you would not see your father again, that he would probably pass.

ESZTER BALINT: Yes, that one was definitely drawn from personal experiences. But again I tried to write it with a voice of slight detachment. Not detachment from emotion altogether, just detachment from the very subjective “feelings.”

PHAWKER: It’s inexact enough that it has a certain universality which is obviously desirable in art.

ESZTER BALINT: Precisely. That was some of the hardest few steps I ever took in my life: that taxi and getting on that plane, and I thought that shit is poweful, there is a story there, a song there. The way the song was recorded it has this sort of funeral procession vibe musically. That is so cool and one of those alchemy things, not to sound all airy fairy – but I never said to JD or the musicians, or even thought to myself: let’s make this sound like a funeral procession. But the way we fleshed out the instrumentation, and performed, it, that’s the form it took. And that couldn’t be more appropriate to the meaning of that song for me.

PHAWKER: And you live in New York can I ask where your father spent his final days?

ESZTER BALINT: He had relocated to Budapest and lived there for about 15 years or so, prior to his death. I had gone there to visit him multiple times during his devastating last few years, including when he was in the hospice dying. . You sort of wish you can time things in this perfect way, so that I could send him off before returning, but that didn’t happen. I had a four year old child here waiting for me and I couldn’t just hang out waiting for him to die. So that’s how that was.

PHAWKER: “Calls At 3 a.m.” which seems like a follow up to the song prior. It seems connected to the song that comes before.

ESZTER BALINT: Yes oh I’m so glad you said that.

PHAWKER: It seems like it was sequenced in that manner and sort of returning back to wherever you came from but feeling lost, in a fog. “Foggy” is repeated over and over again.