BY JONATHAN VALANIA FOR BUZZFEED In 1965, Tacoma, Washington’s The Sonics released a debut album of raw-boned, hemorrhagic garage-punk and maximum R&B called, simply, Here Are The Sonics. Exponentially louder, wilder, and weirder than their woolly-bully frat-rock brethren on the SeaTac teen club/roller rink/armory circuit, The Sonics sang about witches, psychopaths, Satan, and strychnine as a social lubricant, along with the more standard themes of hot girls and fast cars, or, even better, fast girls in hot cars. The 12 tracks on Here Are The Sonics capture the needle-pinning, speaker-blowing, tonsil-shredding, balls-to-the-wall mating call of five hormonal mid-’60s teenage savages forever in hot pursuit of Mad Men-era booze-cigarettes-sex-magic and the glorious din that made it all possible.

BY JONATHAN VALANIA FOR BUZZFEED In 1965, Tacoma, Washington’s The Sonics released a debut album of raw-boned, hemorrhagic garage-punk and maximum R&B called, simply, Here Are The Sonics. Exponentially louder, wilder, and weirder than their woolly-bully frat-rock brethren on the SeaTac teen club/roller rink/armory circuit, The Sonics sang about witches, psychopaths, Satan, and strychnine as a social lubricant, along with the more standard themes of hot girls and fast cars, or, even better, fast girls in hot cars. The 12 tracks on Here Are The Sonics capture the needle-pinning, speaker-blowing, tonsil-shredding, balls-to-the-wall mating call of five hormonal mid-’60s teenage savages forever in hot pursuit of Mad Men-era booze-cigarettes-sex-magic and the glorious din that made it all possible.

Fifty years after its release, Here Are The Sonics still sounds, as one wag aptly put it, “as raw as a freshly scraped kneecap.” On the continuum of rock ’n’ roll as a 20th-century art form, Here Are The Sonics remains a vital and important relic, the aural equivalent of a prehistoric cave painting, as primitive as it is seminal. It changed music. More accurately, it changed the people who would change music.

Jack White called it “the epitome of ’60s punk.” Kurt Cobain said it had “the most amazing drum sound I’ve ever heard…it sounds like he’s hitting harder than anyone I’ve ever heard.” On “Losing My Edge,” LCD Soundsystem’s James Murphy concludes his itemized list of the essential artists in the definitive hipster record collection by invoking The Sonics four times in a row, as if casting a spell.

Feeble national promotion and ham-fisted distribution may have ensured that few outside of The Sonics’ Pacific Northwest stomping ground heard Here Are The Sonics when it was first released, but in the fullness of time its sphere of influence now transcends generations and spans continents thanks to the Esperanto of electrifying noise.

Just don’t tell The Sonics that.

“I think that’s overstating it a little,” says Larry Parypa, 68, The Sonics’ guitarist and de facto leader, when I recite some variation of the last two paragraphs to him. “I’m not sure how much influence we had on rock ’n’ roll.” “Parypa” is a Hungarian name that means “man of strong horse or something,” he says, but I just don’t see it. Parypa is more mild-mannered than you’d expect from a man whose claim to fame is playing guitar on a song called “Psycho,” and, it turns out, is suspicious of grand statements, especially about his band.

“I know we did some things that were very different, but to that degree? I don’t know,” he says with a shrug. We are sitting in the living room of Parypa’s house situated in a leafy suburban cul-de-sac outside of Seattle and paid for not by The Sonics’ paltry record sales royalties (about $4,000 a year) but a decades-long career as an insurance adjuster from which he finally retired earlier this year. He is only mildly amused when I point out that it only took 55 years for the guitar player for The Sonics to finally be able to quit his day job. Parypa is oddly joyless given that the thwarted rock star dreams of his youth have finally come true in his old age. Perhaps he senses, deep down, that it’s come too late.

Parypa is not a sentimental man. You have to look hard to find signs that the guitar player from The Sonics lives here. He doesn’t have copies of the original pressings of The Sonics’ ’60s recordings. No film footage of The Sonics performing live or even a video clip of their 1966 performance on Cleveland’s Upbeat, their one TV appearance. He doesn’t even have any old photos of the band from back in the day. “We just never kept that stuff,” he says, again with the shrug.

There are a few framed gig posters tucked away in an upstairs hallway — but nothing older than five years ago. Parypa never even bothered to tell his now-adult daughter that he was in The Sonics when she was growing up. She had to find out on the street when she was 14. “She must’ve gone to a record store and saw my picture and asked the guy behind the counter and I guess he made a big fuss,” he says, with that I-don’t-see-what-the-big-deal-is tone of voice he adopts when talking about the band. “She came home with a Sonics album and was like, ‘What’s this all about?’”

The reason we are debating the band’s place in the canon of rock ’n’ roll is that a reconstituted Sonics — Parypa, saxophonist Rob Lind, singer-songwriter-keyboardist Jerry Roslie, all three original members, plus bassist Freddie Dennis and drummer Dusty Watson (replacing original bassist Andy Parypa and drummer Bob Bennett, respectively) — are on the verge of releasing This Is The Sonics (out earlier this week), the first proper Sonics album in nearly half a century.

Wisely they enlisted the production services of Detroit garage guru Jim Diamond (White Stripes, The Dirtbombs), who laid down the law on day one.

“I told them, ‘You know, you’re not 19 years old, so it would be silly to try and copy your ’60s records; having said that, we have to stay true to the spirit of those recordings,’” he says a few weeks later, calling from somewhere in the ruins of the Motor City. “I want you to play like you haven’t gotten any better than when you were 19. Raw and mean. If it’s not punk as fuck, I’m not putting my name on it.”

Well, Jim Diamond put his name on it, as well he should. Despite the 48-year gap between albums and the fact that the median age in the band is now 70, one spin of This Is The Sonics makes a persuasive case that The Sonics are still The Rawest Band on Earth. Parypa can still swing a riff like a Louisville Slugger, the drummer still beats the drums like they owe him money, the sax player still honks as if he’s horny, and the singer still sounds like he gargles with gasoline and can’t be trusted with breakable things. All of which means The Rawest Band on Earth are now old enough to be your grandfather — and more popular than they ever were in the prime of their youth.

Anthony Bourdain, host of CNN’s Parts Unknown, used “Have Love, Will Travel” in promos for the current season. He emailed the following when I asked him why: “The Sonics were true originals, garage before garage, the way rock and roll should be: loud, dirty and dangerous.”

The cruel irony of The Sonics story is that Jerry Roslie, the guy who screams like an electrocuted banshee on record and writes songs about guzzling strychnine for kicks and going psycho at the sight of a beautiful lady, is pathologically bashful, bordering on socially phobic, a condition that seems to have worsened over the years. It wasn’t much of an issue when he was living a quiet, anonymous middle-class life in the suburbs of Tacoma, laying asphalt for a living. But all that changed in 2004 when Land Rover licensed The Sonics’ version of “Have Love, Will Travel” for a TV ad, triggering a revival of interest in the band.

In 2007, after years of politely declining lucrative reunion tour offers, The Sonics begrudgingly agreed to reunite for one night and perform a completely sold-out show at the Cavestomp! garage-rock festival in New York. Backstage before they went on, everyone had butterflies — after all, it had been 40 years since they plugged in together — but Roslie was scared shitless. Could he still do this? Did The Sonics still have it? Would the audience laugh at these sad old men trying to relive long-past glories? “We heard that New York can be a pretty tough crowd,” he says. “I remember before we went on looking around for a garbage-can lid to shield me from the rotten fruit and vegetables. When they opened the curtain it was like déjà vu, spooky, we’d gotten older but the audience was the same age as they were when we played back in the 1966. And they welcomed us right away.” And 21st-century audiences have been welcoming them ever since.

In the eight years since they played CaveStomp, The Sonics have crisscrossed the globe repeatedly — not bad for a band that never got farther east than Cleveland back in the day. “We’ve played in European countries where they don’t speak much English,” says Lind. “And the crowd is down at the front of the stage singing every word of ‘Strychnine’ and waving their beer bottles.” When The Sonics played Mexico City last summer, they were so mobbed by autograph seekers after the show it took half an hour to go the 20 feet from the backstage door to the shuttle van. When they played in Spain, grown men cried in their dressing room, begging to touch the hem of their garments. Two months ago they flew to São Paulo, Brazil, for a completely sold-out one-night stand. The next morning they were mobbed in the hotel lobby by autograph seekers. One eternally grateful fan passed the band a handwritten note with the following message.

To The Sonics

Thank you for existing and the good job you did (and still doing) for mankind.

Big Respect,

Rodrigo

Sao Paulo, Feb. 2015

Not too shabby for an ex–insurance adjuster, retired commercial airline pilot, former proprietor of an asphalt paving business, laid-off Experience Music Project tour guide, and the guy who played drums for Lita Ford from 1980 to 1984.

Tacoma and all points in between. Every red-blooded, non-jock male under 25 has a rock ’n’ roll band. Or wants to start a rock ’n’ roll band or just got kicked out of a rock ’n’ roll band or at the very least goes out to see rock ’n’ roll bands all the time. Because that’s where the girls are. Jerry Roslie and Rob Lind are no exception. Roslie plays keyboards and Lind blows sax. Their band is called The Searchers. “We started going out on Saturday nights on a dual mission and the mission was: hear rock ’n’ roll bands and meet women,” says Lind, a recently retired US Airways pilot, on the phone from his home in North Carolina. “We’d see something cool and then go home and try and play it and kinda get it wrong, but in the process make something that was ours.”

One Saturday night they met a guitar player named Larry Parypa, who had an instrumental band with his brother Andy called The Sonics — named after the sonic booms emanating from nearby McChord Air Force Base. But something was missing. Like Lind and Roslie, the Parypa brothers liked their rock ’n’ roll loud and mean. They quickly agreed to join forces and ditch The Searchers moniker in favor of The Sonics, which was wise because there was already a band called The Searchers in the U.K., with actual hits. By process of elimination, Roslie became the band’s lead singer. He was the least bad of the bunch.

“People always ask me how come you guys are so nasty and dirty, and I always tell them that Seattle bands were jazzy and swingy and really good musicians,” says Lind. “Down in Tacoma, where we grew up, it was a blue-collar city, our fathers all worked in mills and on the waterfront and all we wanted to do was rock ’n’ roll. We wanted to kick your ass.”

“We all wanted to play hard music, and it got so aggressive,” says Parypa. “We wanted loud drums and back then you didn’t mic the drum kit, so if you wanted loud drums the drummer had to hit really hard. That meant everybody else had to turn up to be heard over the drums, and Jerry would have to scream to be heard over the din. And that just became our sound.”It was slow going early on, but soon they landed a regular Friday-night gig at a teen club called the Red Carpet, which would become for them what the Cavern Club was for The Beatles: the place where they got their chops from playing marathon four-hour sets nightly, learned their lessons about stagecraft the hard way, and began harvesting the fruits of their labor, namely girls and beer. “After a while, we’d pull up to the back to load in our gear and there would already be a line of kids waiting to get in that stretched around the block,” says Lind.

Some nights Roslie’s preternatural bashfulness would get the best of him and he’d succumb to debilitating stage fright. “He’d look out at a packed crowd and turn to me and say, ‘I’m not singing tonight!’” says Parypa. “I’d be like, ‘But you’re our singer!’”

The Sonics soon caught the attention of Buck Ormsby, bassist from The Wailers, who had started Etiquette Records to put out his band’s recordings and harvest local talent. He told them if they had a record under their belt, they could command at least twice the $500 they were pulling down a night at the Red Carpet. But to make a record you had to have some original material, and at that point The Sonics were still just a cover band. Roslie went home that night and wrote a this-evil-chick-done-me-wrong song, as was the style of the day, around a catchy stair-stepping riff that — when played simultaneously by the guitar, sax, and organ — sounded as menacing as the title. He called it “The Witch.” Ormsby liked what he heard and took the boys into a two-track studio in Seattle that was primarily used to cut ad jingles.

“We were all of 17 and so keyed up and nervous that when they pressed ‘record’ we played it three times as fast as it was supposed to be,” says Lind. “I remember afterwards laying on the living room floor at the Parypas house and listening to the master, and all of us were distraught. We felt like we’d totally screwed it up and we’d spent $500 of our own money to record it.” The Parypas brothers’ father was so incensed he called up Ormsby and threatened to drive over to his house and punch his lights out for ruining his sons’ budding musical career.

Six months later it was a hit.

Despite the phone ringing off the hook with requests for “The Witch,” the big Seattle radio station WKJR refused to play the song before 3:30 p.m. — when the kids were home from school — for fear this creepy, lo-fi song about a witch would scare off the lucrative daytime homemaker audience. Despite such restrictions, the single sold 20,000 copies in the first week of its release. “The record label was like, ‘Holy crap, you guys are hot! We have to follow this up with an album!’” says Lind. “And we were like, ‘OK, when are we going to make this album?’ They said, ‘Tomorrow.’”

That night after playing their standard four-hour set at the Red Carpet, they asked the owner if they could stay and rehearse for a few hours. They worked up a couple numbers that Roslie had been chipping away at: “Boss Hoss,” inspired by a bitchin’ red Mustang he saw in a hot-rod magazine; and “Strychnine,” a bitter white crystalline powder widely used as a rat poison that causes convulsions and death through asphyxia in humans. It was also widely rumored at the time that LSD was cut with strychnine, which turned out to be a myth spread by law enforcement types to discourage use of the hallucinogen. A third original, the aptly titled “Psycho,” was made up on the spot that night. The rest of the album would be fleshed out with covers from their live set, including their now-iconic version of Richard Berry’s “Have Love, Will Travel.”

Lind remembers the recording session was booked for the middle of the night to get a cheaper rate. “We used to call Etiquette ‘Cheap Screw Records,’” says Lind. “It was like 3 a.m. Everything was done in one take. We’d be like, ‘We could probably play it better if we did it again.’ And the engineer would be like ‘Naw, sounds great, let’s move on.’ I remember the top of the piano being covered with burgers and soda cups and there was this thick fog of cigarette smoke.”

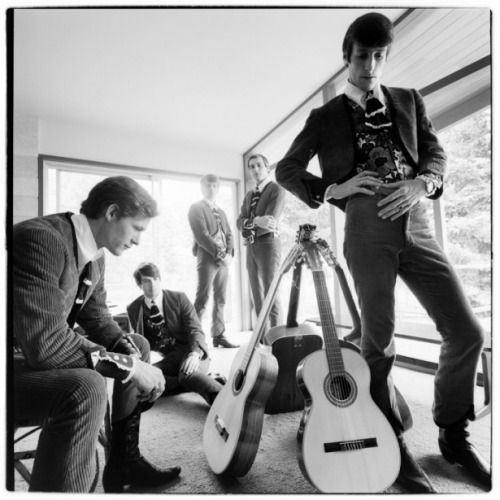

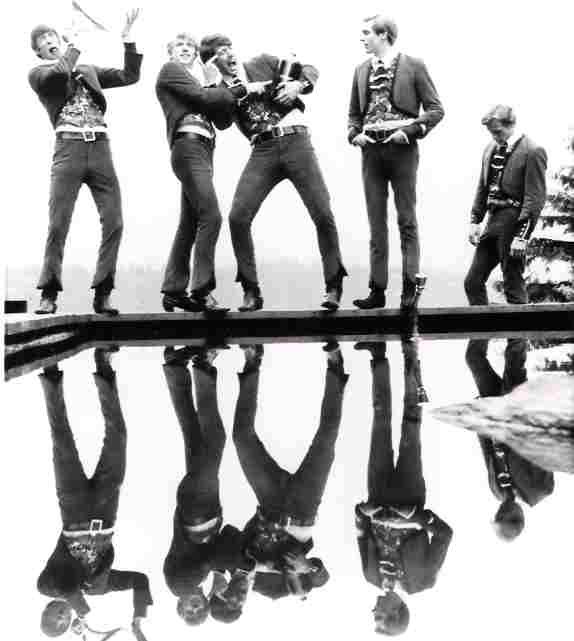

Etiquette hired famed rock photographer Jini Dellaccio to shoot the band for the cover. Formerly a fashion photographer, Dellaccio had started turning her lens on the moody, hirsute young men that peopled the local music scene with striking results. Always shooting in black and white, Dellaccio eschewed the fussily arranged studio setups that were de rigueur at the time in favor of spontaneous shots taken in rustic outdoor settings near her home along the waterfront.

The Sonics’ debut sold well in the Pacific Northwest but distribution snafus kept the album from breaking nationally. “They would start playing it on a radio station in Miami, but by the time they got the records into stores there, the radio station had moved onto other things and it died on the vine,” says Parypa. “I think that kind of thing happened a lot.”

Still, Here Are The Sonics opened a lot of doors for the band — including regional tours with The Kinks, The Mamas & the Papas, and the Beach Boys — and tripled their asking price for headlining gigs. “I remember the first time we got paid $1,500, boy, we felt like we were The Rolling Stones,” says Lind. And in a big-fish-little-pond way — getting drunk with The Kinks, trading backstage pranks with the Beach Boys — they were. After all, The Sonics’ prime directive always was and forever shall be getting laid, and, for a time at least, it was raining women. And when it rained it poured.

“We did not want for female attention back then and sometimes that caused problems,” says Lind. “We used to play a lot out in cowboy country. Not a lot of people know this but if you go over the Cascade mountains, all of eastern Washington is like Kansas, basically one big wheat field and combines. So when we would play out that way; lots of dudes would come to the shows in pickup trucks wearing cowboy hats and plaid shirts with the sleeves rolled up. Well, their girls were attracted to us — we were young, skinny, good-looking guys and we’re up there playing rock ’n’ roll music.” This kind of thing happened all the time. Invariably the band would be cordially invited by jealous boyfriends to discuss the matter over knuckle sandwiches in a darkened alley behind the club. It got to the point that The Sonics guys started learning karate.

It wasn’t just jealous boyfriends they had to worry about. Though it’s hard today to understand what all the fuss was about, in 1965 — especially in the rural redoubts of the Pacific Northwest — having hair longer than a buzz cut marked you as some kind of beatnik-commie-queer. “We’d stop at some gas station out in the middle of nowhere and we’d ask directions how to get back to the interstate and the owner would say, ‘Oh sure, boy — say, are you a boy or a girl?’ Ha ha. Like we hadn’t heard that a million times,” says Lind. “Then he’d give us directions and we’d thank him and soon find out the directions lead to the middle of nowhere. We used to refer to them as ‘Sonics Directions.’”

They toured around in a shit-brown ’62 Ford van they christened The Turd. “When the sun hit at a certain angle you could see there was some writing on the side of the van that said EAT OUT MORE OFTEN,” says Jerry Roslie. “We couldn’t stop laughing about that, because, well, we were 18.”

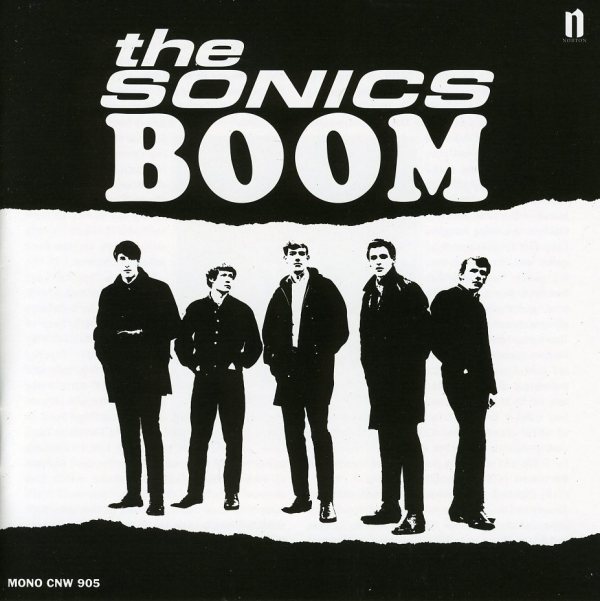

When Etiquette decided they’d played out the string on the first album, it was time to record another one. Tomorrow. “Again, we had, like, no songs,” says Parypa. Though many rock snobs worship at the temple of Boom, which is widely recognized by the iconic Jini Dellaccio shot of the band on the cover — five tall drinks of water dressed head-to-toe in midnight-black and Beatle boots, elegantly staggered and striking poses of sullen teenage cool before a backdrop of whited-out oblivion — musically speaking it’s kind of a wet firecracker. The frantic energy of the debut has dissipated, Roslie largely abandons his lacerating vocal style, and the improved clarity of the recordings doesn’t really do the band any favors. The Sonics always did their best work in the murk.

By early 1966, when Boom was released, the times were clearly a-changing. The Beatles and the Beach Boys and Dylan had moved the game to a whole new level. Recording artists were expected to be poets and seers taking rock ’n’ roll to strange new places — places well beyond The Sonics’ reach as songwriters. They were primitives in a new age of artistes. Not that they didn’t give it the old college try. In late ’66 they jumped to Jerden Records, a Seattle label with deeper pockets thanks to labelmates The Kingsmen’s million-selling version of “Louie Louie.” Jerden sent them to Hollywood to record at Gold Star Studios, hoping for higher fidelity and a more current sound. It was a disaster. “We wound up hating it,” says Lind. “We’d just as soon forget that one.” The band disowned the record before it was even released, and it died a quick and ignominious death upon arrival. In the aftermath of their ill-advised slouch toward the fringes of competence, finesse, and commercial viability, The Sonics crumbled like vampires in the dawn’s early light of psychedelia, and its members soon vanished into the jungles of Vietnam, straight jobs, and the middle-class domestic tranquility of the suburbs from whence they came.

Which brings us back to where we started. The sun is going down on Larry Parypa’s house. The man of strong horse is looking a little saddle sore. He’s dreading the epic trek to São Paulo next week. “It will be fun to play in Brazil, but that’s going to be a horrible flight,” he says. The band’s upcoming coast-to-coast U.S. tour — a first for The Sonics — is also cause for concern.

“I live for that hour on stage, but everything else is bullshit,” he says. “You’re always tired, you get home at 2 a.m. but you’re kind of hyper, and you’ve got to be in the lobby at 6 a.m. to go some other place. And then when you get there, they want to do interviews and all that stuff. I hate waiting, I hate sitting in those little cramped greenrooms, I hate airplanes.”

Though The Sonics have managed, thus far, to defy the restraints of senior citizenship, time waits for no man. Not for very long, anyway. None of them are getting any younger. At 65, Freddie is the baby in the band. Lind and Roslie are septuagenarians, and Parypa is not far behind. Not to mention Roslie underwent a heart transplant back in 2008. Let’s face it, rock ’n’ roll is no country for old men. I ask Parypa how much longer he thinks The Sonics can keep this up. “I ask myself that all the time,” he says. “I asked Jerry about that like three weeks ago. He’s in the same boat, like, ‘When do we quit, man?’”