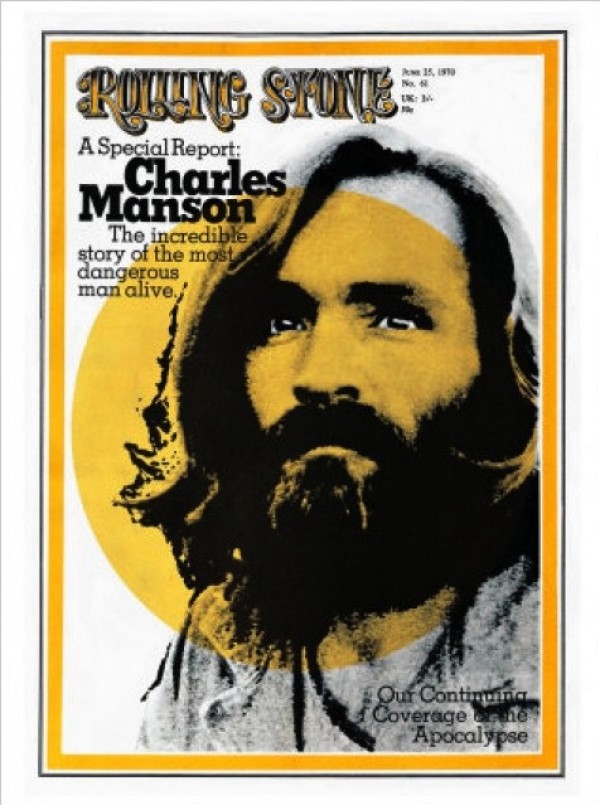

ROLLING STONE: He doesn’t look how he used to look, of course, all resplendent in buckskin fringe, sometimes sporting an ascot or the Technicolor patchwork vest sewn by his girls, with his suave goatee and his mad Rasputin eyes and his fantastical ability to lunge out of his seat at the judge presiding over his trial, pencil at the ready to jam into the old guy’s throat, before being subdued and thereby helping to cement a guilty verdict. Those days are gone. He’s 79 years old. He’s an old man with a nice head of gray hair but bad hearing, bad lungs, and chipped-and-fractured, prison-dispensed bad dentures. He walks with a cane and lifts it now, in greeting to his visitors, one of whom is a slender, dark-haired woman he calls Star.

“Star!” he says. “She’s not a woman. She’s a star in the Milky Way!”

He shuffles toward her, opening his arms, grinning, and she kind of drifts in his direction.

From a raised platform in the room’s center, two guards armed with pepper spray and truncheons keep an eye on the couple. Star is 25 years old, comes from a town on the Mississippi River, was raised a Baptist, keeps a tidy home, is a prim dresser, has a fun sense of humor. Charlie is probably the most infamous convicted killer of all time. He’s been called the devil for the way he influenced friends to murder on his behalf. He’s spent the past 44 years in prison and nearly 60 years incarcerated altogether, meaning he has spent less than two decades of his life as a free man. He will never get out. For her part, Star has been living in Corcoran for the past seven years, since she was 19. It wasn’t Charlie’s murderous reputation that drew her here but his pro-Earth environmental stance, known as ATWA, standing for air, trees, water and animals. She has stuck around to become his most ardent defender, to run various give-Charlie-a-chance websites (mansondirect.com, atwaearth.com, a Facebook page, a Tumblr page) and to visit him every Saturday and Sunday, up to five hours a day, assuming he’s not in solitary or otherwise being hassled by the Man. “Yeah, well, people can think I’m crazy,” she likes to say. “But they don’t know. This is what’s right for me. This is what I was born for.”

Visiting-room rules allow them a kiss at the beginning and end of each visit. They do this now, a standard peck and hug, then sit across  from each other at a table. The first thing you notice about Manson is the X (later changed to a swastika) he carved into his forehead during his trial, to protest his treatment at the hands of the law, an act that was soon copied by his co-defendants – and, all these years later, by the girl sitting across from him, Star, who recently cut an X into her forehead, too. The second thing is how nicely turned out he is. Despite his age, there’s none of that gross old-man stuff about him, no ear hair, no nose hair, no gunk collecting in the corners of his mouth, and his prison-approved blue shirt has not a wrinkle or a food stain on it. He looks pretty great. The third is how softly he speaks, so different from how he was in TV interviews during the Eighties and Nineties, when, for instance, he angled in on Diane Sawyer in her black turtleneck and pretty earrings, roaring, “I’m a gangster, woman. I take money!”

from each other at a table. The first thing you notice about Manson is the X (later changed to a swastika) he carved into his forehead during his trial, to protest his treatment at the hands of the law, an act that was soon copied by his co-defendants – and, all these years later, by the girl sitting across from him, Star, who recently cut an X into her forehead, too. The second thing is how nicely turned out he is. Despite his age, there’s none of that gross old-man stuff about him, no ear hair, no nose hair, no gunk collecting in the corners of his mouth, and his prison-approved blue shirt has not a wrinkle or a food stain on it. He looks pretty great. The third is how softly he speaks, so different from how he was in TV interviews during the Eighties and Nineties, when, for instance, he angled in on Diane Sawyer in her black turtleneck and pretty earrings, roaring, “I’m a gangster, woman. I take money!”

He stands up and looks around. “I thought we’d have some popcorn,” he says, making his way to a cabinet where inmates sometimes stash food. He bends down, looks inside, moves things and heaves up a great sigh of disappointment.

“Well,” he says. “The popcorn’s all gone.”

“I think we ate it all last time,” Star says.

Charlie sighs and takes a seat, seeming lost and befuddled. But then, before I know it, he’s reached out and bounced one of his fingers off the tip of my nose, fast as a frog’s tongue, dart and recoil.

He leans forward. I can feel his breath in my ear.

“I’ve touched everybody on the nose, man,” he says, quietly. “There ain’t nobody I can’t touch on the nose.” He tilts to one side and says, “I know what you’re thinking. Just relax.” A while later, he says, “If I can touch you, I can kill you.”

He puts his hand on my arm and starts rubbing it. An hour after that, we’re talking about sex at the ranch in the old days, what it was like, all those girls hanging around, a few guys, too, the group-sex scene. “It was all this,” he says, putting his hand on my arm again, sliding it up into the crook of my elbow and down. “That’s what it was like. We all went with that. There’s no saying no. If I slide up, you’ve got to go with the flow. You were with anyone anyone wants.” I nod, because for a moment, with his hand on my skin, sliding up, I can see how it was. It feels OK. It feels unexpectedly good to go with the flow, even if it is Charlie Manson’s flow and even if, since he’s touching me, he can kill me, which is probably how it was way back when, too. MORE

RELATED: The Life And Times Of Charles Manson