Illustration by ALEX FINE

EDITOR’S NOTE: To mark the passing of Devo drummer Alan Myers guitarist Bob Casale on Monday, here’s an encore posting of our 2008 Q&A with Devo mainman/Hollywood film score composer Mark Mothersbaugh, arguably among the most interesting we’ve been lucky enough to have on the site. Enjoy.

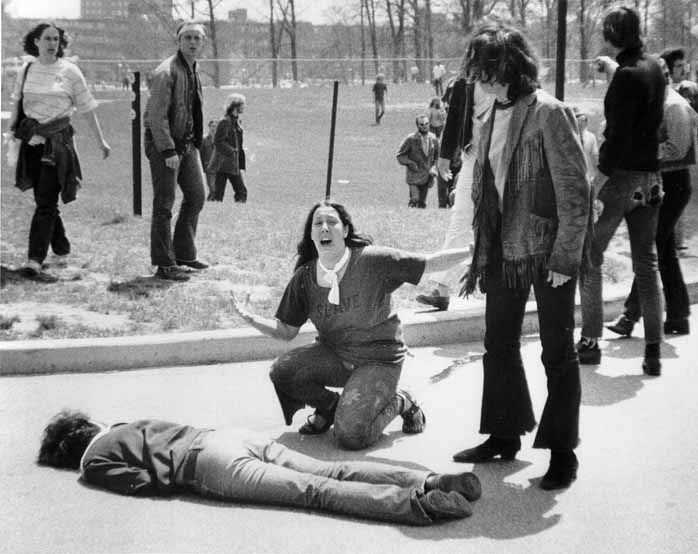

Phawker: Let’s start with ancient history, I want to know about the evolution of the Devo idea, I’ve read conflicting things — that it was started sort of as a joke in the late 60s and then the shootings at Kent State radicalized you guys, tell me about that time.

Mark Mothersbaugh: OK, I don’t know what you read, but I’m sure there’s plenty of people putting false information out there and this is the true story: The band happened, when I met Gerald Casale at Kent State, we were both in the Fine Arts department. We were protesting the war in Cambodia, ’cause there was evidence we had been invading Cambodia, and then all hell broke loose and they killed a bunch of kids and closed down our school.

closed down our school.

Phawker: Were you there that day?

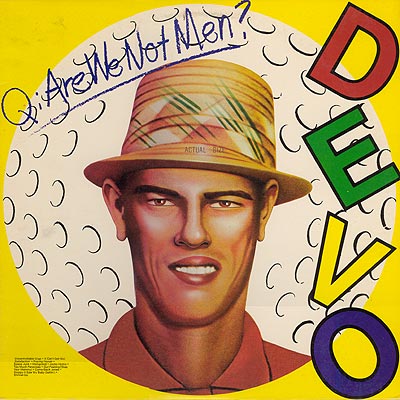

MM: Yeah we were there, spring of 1970, the school got closed down, so Gerry came to my place and we wrote music together. At the time, he was playing bass in a blues band at the time and I had kind of a trippy Soft Machine electronics band. And we got to talking about the world and what we saw surrounding us and decided that it wasn’t evolution that we were seeing happening — and not just referring to Kent State, but to everything. We were trying to put a name on the phenomena that was going on. We thought that Devolution fit it better. Anyway, we started writing music together and thought of ourselves as Fred Flintstone meets George Jetson, kind of, because at that time the artists that were influencing us were Rauschenberg, Lichtenstein, and Andy Warhol — so we were influenced by a mixture of commercial art and fine art. We were purveyors of lowbrow and highbrow colliding, you know those Venus De Milo statues with a clock in the stomach? That kinda stuff. You didn’t even have to go that far, you could just walk through a K-Mart at the time and it was even funkier then than it is now. I remember seeing this beautiful airbrushed photo of Chi Chi Rodriguez, with his head over a golf ball, and it kind of mimicked an astronaut’s head in front of the moon. But it was this golfer’s head over a golf ball, and they used that logo on a line of products that were manufactured in China. So I bought it, ’cause it was the cheapest thing you could buy, golf tees with a little hanging bag, with Chi Chi Rodriguez‘s head in front of a golf ball. And we later ended up using that as the inspiration for our first album cover.

The only guys we could find to play the music we were writing were our younger brothers. At one point the band was Bob Mothersbaugh, Jim Mothersbaugh, Mark Mothersbaugh, and Gerry. Then it was Gerry Casale, Bob Casale, Mark and Bob Mothersbaugh, and then Jim was in the band for awhile, then he became obsessed with inventing the first electronic drum machine. We kept pushing him to make drums sound like V2 rockets and mortar blasts, and he started working on that. That’s where Devo started — we had a sense of humor, but we were very serious about the things we were joking about.

The only guys we could find to play the music we were writing were our younger brothers. At one point the band was Bob Mothersbaugh, Jim Mothersbaugh, Mark Mothersbaugh, and Gerry. Then it was Gerry Casale, Bob Casale, Mark and Bob Mothersbaugh, and then Jim was in the band for awhile, then he became obsessed with inventing the first electronic drum machine. We kept pushing him to make drums sound like V2 rockets and mortar blasts, and he started working on that. That’s where Devo started — we had a sense of humor, but we were very serious about the things we were joking about.

Phawker: It was humor with a serious intent.

MM: Yeah. Ironically enough, a lot of our image problems came not from inside us but were generated by our record company, who I think was just flummoxed about what we were about, who we were, and what we were doing. And instead of taking us seriously, they chose to call us as Nazi weirdos or Nazi clowns or just, wacky, zany, goof balls. Because that was what they could understand in a world of people they spent their lives building and marketing things like Rod Stewart albums and Madonna albums. Devo had to be wacky and zany, we just couldn’t be talking about anything serious.

Phawker: It was totally questioning all of the premises that those artists were based on, correct?

MM: Yes. From the very beginning, when we were going on stage we looked for the most anti-rock and roll outfits we could find, we didn’t want to look like those people, let alone sound like them. So Gerry worked for a janitorial supply company, he did graphic work for them, and I was a maintenance man for an apartment building, and so we had these janitorial supply catalogs and we’d look through and we’d lust over things like 1-inch thick ruby silicon sheets [that were] 3 feet by 8 feet. You would use them to put on a floor when you were working in a kitchen, an industrial kitchen or in an automotive place. But we would think about the materials they had available and think of how to use them in creative ways. We came across these hazardous waste cleanup outfits, for cleaning up liquid hazardous waste. They were these two-piece, plastic coated paper outfits and we adopted them as our own. We figured, that kind of described our jobs in life; we didn’t think of ourselves as musicians, certainly not as rock ‘n rollers, we thought of ourselves as musical reporters, reporting the good news in devolution. Our experiences in Ohio were to be greeted with anger and we were kind of a lightning rod for hostility back in those days.

think of ourselves as musicians, certainly not as rock ‘n rollers, we thought of ourselves as musical reporters, reporting the good news in devolution. Our experiences in Ohio were to be greeted with anger and we were kind of a lightning rod for hostility back in those days.

Phawker: I can imagine.

MM: I understand where it came from, that was not a surprise. People who [at] my age, or a year or two older, or a year or two younger, went off to Vietnam, came back, and expected to get the same jobs their fathers had, and their grandfathers had, working in a rubber factory. Because rubber was the life of Akron, Ohio when I grew up. Akron, between World War I and World War II became the rubber capitol of the world, actually. More tires and products that would get shipped up to Detroit and all over the world came out of Akron. Everybody, even if you had a doughnut factory, everybody worked for the companies, and you worked for rubber.

DEVO: Uncontrollable Urge

Phawker: When I was young my grandfather told me that Vietnam was all about the auto companies trying to get the rubber.

MM: There you go, I can believe that. I mean, ‘no it was about the spreading of democracy and curtailing of the spreading of communism.’ Don’t you read your history books? Anyhow, these guys were my age and they would come back from Vietnam disillusioned, but looking for work, and find out that all the factories closed down in a very short amount of time. By the mid-70s it was a ghost town, and there was no work. There were thousands and thousands of people laid off and people that came back from Vietnam who couldn’t find work, and these were the people coming to our concerts. There’d be these bummed-out, unemployed, rubber-working ex-GI’s who probably got into drugs in Asia, and they just wanted to hear some songs by their favorite bands before they went home and beat their wives.

We kind of spurred the hostility on, we’d lie and say we were a Top 40 cover band so that we could play the clubs in Akron. After about five songs or six songs we would say, ‘OK here’s another one by Foghat, it’s called Mongoloid!’ There’d be these long-haired, bummed-out guys who would be like ‘That’s it!’ They’d come up and stop the show and we’d get into fistfights. We were a lighting rod for hostility. But I think  probably we did the feminist movement of Akron, Ohio some good, in the fact that being a lightning rod we probably deflected a lot of the energy that would have normally would have not dissipated until they got home.

probably we did the feminist movement of Akron, Ohio some good, in the fact that being a lightning rod we probably deflected a lot of the energy that would have normally would have not dissipated until they got home.

Phawker: Let’s back up before that, back to childhood, you were legally blind until age seven?

MM: Yeah there were five kids in the family, what can ya say?

Phawker: Where did you rank in there?

MM: Up at the top, but it seemed like my mom was having a new kid every two months. So we were all really close in age and they just thought I was a little freakier than the other ones. Because I would get up in front of everyone’s face to talk to them and I didn’t have any respect for personal space. They were like, OK, he’s a little overly intense. It never translated into not being able to see, because I never complained about not being able to see. I just didn’t know people saw things differently than I did. I don’t know, the added bonus was it was a treat when I finally got a pair of glasses and got to observe Akron the same way other people did, from more than 6 inches away.

Phawker: How do you think that impacted you as a visual artist, all those years with essentially a different set of eyeballs?

MM: I’m sure it had an influence; it gave me a different way to relate to things I saw visually.

Phawker: When did you become artistic, when did you start expressing yourself that way, visually or musically?

MM: Well, funny you should say that. After I got my glasses, I was kind of impressed by everything I saw, and I drew a lot. My schoolteacher, who had been spanking me — corporal punishment was encouraged in those days, ‘Spare the rod, spoil the child’– Mrs. Savory was watching over my shoulder when I was drawing and said ‘You know Mark, you draw trees better than me.’ And this was the first time she wasn’t saying,’ I said what was on the blackboard and you make a smart-ass comment,’ so instead of getting swatted or put in the corner, she complimented me, and I remember I went home and had a dream that I was going to be a famous artist. I was sure I was going to be Rembrandt or one of my heroes at the time, like Da Vinci and Van Gogh, and I just loved colorful and beautiful art, and the idea that someone could do that with their hands, that someone could render that.

Van Gogh, and I just loved colorful and beautiful art, and the idea that someone could do that with their hands, that someone could render that.

Phawker: So then, you guys make a film?

MM: In the Beginning Was The End: The Truth About Devolution.

Phawker: Which gets screened at a festival in Ann Arbor, and is championed by David Bowie and Iggy Pop?

MM: It eventually gets to them, yeah. Within a year, it went around the planet in different film festivals and they see it. I remember Iggy Pop showing up at a Devo show in 1977, we were playing at the Starwood in Hollywood. And he comes back and he is singing these songs, and he knows songs we didn’t even play that night, like “Praying Hands.” And we go, ‘How do you know these songs?’ and he goes, ‘Because David Bowie and I, when we did our album in Berlin, we were looking for music to listen to and he has this cassette you guys had some girl give him backstage in Cleveland. And we didn’t believe that it was really a band, so we used to play all these songs in Germany to entertain ourselves. We’d play it in the studio.’ We go, ‘You’re not Iggy Pop!’ and he said he was Iggy Pop. We said, “No, you’re not,” and he said ‘Shut up, I cut my hair off.’ And in fact it was Iggy Pop. So he got us in contact with David Bowie, and the rest is devolution.

Phawker: Now was this just a phone thing or did you guys meet in person?

MM: What happened was we went back to Ohio, in our little Econoline van, because there wasn’t anything in between Cleveland and San Francisco and Los Angeles and New York, those were the only four places we were allowed to play. So when we back out to the East Coast a couple weeks later, Brian Eno and Robert Fripp came out to see us. Brian Eno said he wanted to produce us and we said ‘Great!’ Then we played the next weekend and David Bowie shows up and says, ‘I want to produce you!’ And we said, ‘that’d be great!’ So Bowie came on stage with us at Max’s Kansas City and said ‘This is the band of the future and I’m going to produce them in Tokyo this winter!’ And I remember we were standing there onstage thinking ‘That’s great, cause we live in an Econoline van right now and that’s where I’m sleeping tonight. Tokyo sounds great, I’ll bet you dont sleep in a van.’ Then Bowie and Eno started bickering and Robert Fripp got into the frame. Bowie said, “The only caveat to this is, if I get this part in this movie, I’ll be in Berlin filming and we’d have to wait till spring or summer.’ And he called the next day and said, ‘I just got the part for this movie The Gigolo’ or something, a German art film.

So he was in Berlin filming, and we were like, ‘Whoa that sucks, cause we don’t even have apartments in Akron and it’s freezing here.’ So Brian Eno said ‘You know what, I’m just gonna fly you guys over to Neunkirchen where I record my music,’ and we said OK. He said, ‘I know we’ll get a record deal.’ So he flies  to Neunkirchen and Bowie was in Berlin, and he would come down on the weekends and visit us. So we recorded our first record with Eno and Bowie hung out on weekends, and at dinner they would quibble. Eno felt he wasn’t given enough credit for his contributions to Low. And they would argue about this stuff.

to Neunkirchen and Bowie was in Berlin, and he would come down on the weekends and visit us. So we recorded our first record with Eno and Bowie hung out on weekends, and at dinner they would quibble. Eno felt he wasn’t given enough credit for his contributions to Low. And they would argue about this stuff.

Phawker: That’s too funny. The two most urbane men in rock getting petty.

MM: The day we were just about to finish the album in Germany, someone walked in with the new Melody Maker, and there was a little picture of Bowie in the right-hand corner and there was a picture of Devo all over the cover, it was a publicity photo we made at the Goodyear Tire and Rubber Museum in Akron, and we’re all posing around these pipes and valves and dials and acting like we’re scientists working in a factory, the five of us. Bowie’s picture is inset in the corner of the magazine and it had him saying, ‘This is the Band of the Future, Devo.’ We had let Stiff Records put out some singles we recorded in Akron, like about two months before we started on the album. They said ‘Hey let us put out “Mongoloid, “Jocko Homo,” “Satisfaction” and “Social Fools,”‘– and we couldn’t give them away back home. I’d get in a car and go from Akron to Cleveland and I would go into a record shop and say ‘Hey, need some more Devo records” and the guy would walk down to the last little spot he had in his store, under OTHER, and he’d go ‘Nope, still got the one you brought in last week.’ And I would go ‘OK,’ and I would get in my car and go to the next record store.

Phawker: “Jocko Homo” came from a pamphlet, I read, what’s the story with that?

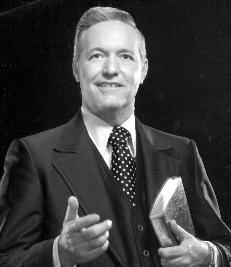

MM: It came form a couple places. We grew up in Akron, Ohio, and we were keenly aware that it was an early capitol of televangelism. There was somebody called Rex Humbard, who had the Cathedral of Tomorrow, which was a big circular building, that inside it had this gigantic cross — it must have been a football field-sized cross on this ceiling. He was this Huckster Hillbilly, who hadbadass children who were always getting in trouble with the law. But he preached on TV, which was radical back in the 60s. There was this other guy in Akron named Reverend Ernest Angley, and Ernest Angley became famous because not only was his wife buried in the mausoleum on the same property of his church, the Grace Cathedral, but he had a line between his office and her mausoleum so he could talk to her. Which was cool, even better than that, he invented instant-replay miracles, ’cause crippled people would come on stage and he would go ‘And the other children made fun of youuuu didn’t they? I say your DEVIL COME OUT!’ and these people would fall backwards and two of his aides would catch them and he would go ‘And you can hear now can’t you?’ and they would go ‘Oh My Gawd’ and he would go ‘Say ‘baby!’ and they would say ‘Baaabby, Baaaaby’ and he’d go ‘It’s a miracle!’ Then at the end of the show, you would see all the people he healed a half an hour earlier, because they would be assembling all the video footage, and then you would get to see the instant replays.

So we were keenly aware of televangelism, and I had this rickety old apartment building where I was a maintenance man, and I got routinely get attacked by Jehovah’s Witnesses. And I started inviting them in when I realized that the magazines Awake and Watchtower were virulently anti-evolution, so you could get all this get anti-evolution information. They weren’t pro-devolution, they were something else. They were pro-The Miracle of God, and I was looking for stuff they had put together that was anti-evolution. In the process, I found this pamphlet by someone named Reverend Shaddock, and he had put out something called From Puddles to Toadstools. They were anti-evolutionary, very reactionary, anti-Darwin. And he did one called Jocko Homo: Heaven Bound King of Earth. In it, there’s a page where there’s a picture of this hairy, stubbled devil and he had one hoof then one other foot, a tail with an arrow and a horn and a really mean look. And he was holding a pitchfork, and he was putting on this professorial mask, and it said ‘Evolvo-Spoofus’ under it, and the devil’s winking from under this caucasoid mask he’s putting on. And the Devil has a hook nose.

when I realized that the magazines Awake and Watchtower were virulently anti-evolution, so you could get all this get anti-evolution information. They weren’t pro-devolution, they were something else. They were pro-The Miracle of God, and I was looking for stuff they had put together that was anti-evolution. In the process, I found this pamphlet by someone named Reverend Shaddock, and he had put out something called From Puddles to Toadstools. They were anti-evolutionary, very reactionary, anti-Darwin. And he did one called Jocko Homo: Heaven Bound King of Earth. In it, there’s a page where there’s a picture of this hairy, stubbled devil and he had one hoof then one other foot, a tail with an arrow and a horn and a really mean look. And he was holding a pitchfork, and he was putting on this professorial mask, and it said ‘Evolvo-Spoofus’ under it, and the devil’s winking from under this caucasoid mask he’s putting on. And the Devil has a hook nose.

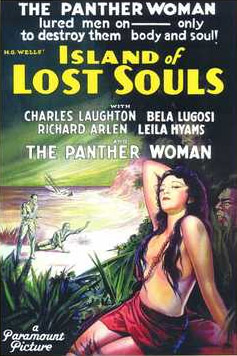

Anyhow, on this one the Devil is pointing up a staircase and it has things that say World War, Cock Fighting, Drug Use, Slavery, and then one step closer to heaven is White Slavery, meaning, you know, he is pointing up this ladder and it says evolution after two million years. Making fun of the idea that man is more than 3,000 years old, or how ever long theliteralists were saying. They were saying that the Bible says that the world was created 3,612 years ago, or something like that. I had a collection of stuff, one pamphlet called It Does Make a Difference, What I Believe, and it had this earnest-looking World War II-era worker on the cover, with his brows all knit and his sleeve rolled up, and he has Osh Kosh B’Gosh jeans on, and he looks like he is on his way to build aircraft for World War II or something. The first lines were, ‘Wean your children with gin or milk, shine your shoes with black or brown, it makes no difference,’ and it was talking about the insanity of Darwinism. At the same time I collected those, I used to watch late-night TV and watch the movies and I found this movie Island of Lost Souls, and it was made in 1933, Bela Lugosi, Lon Cheney, and Charles Laughton plays this scientist who is on a deserted island in the Pacific somewhere, and he is experimenting on the animals that live in the jungle, and he is trying to evolve them up the ladder of evolution.

His laboratory is called the House of Pain and the animals are all afraid of it, because it is painful what he does to them to evolve them up. Most the experiments are all failed, so you see all these half-human, half-animals creeping around the outskirts of his compound. There was one that was fairly successful, a woman namedLota, who you find out was a tiger or something. These animals keep devolving, as much as he fights, using his technology and his expertise to evolve them up to full human status, they never quite get there, and most of them are failed, and they keep devolving back to the beasts they once were. He keeps them in control with a whip and a mantra, when they start acting crazy he cracks this whip and goes ‘What is the Law?’ and they all have to recite, ‘Not to walk on all fours, are we not men?’ ‘What is the Law’ ‘Not to shed blood, are we not men?’ I don’t know, just something about watching that on a 9-inch black-and-white set, late at night, that I had in my one-room apartment, and there;s this one scene where they rebel against him, and there is a fire in the jungle and it’s casting their shadows onto the House of Pain, and these disfigured sub-humans are trudging, waddling, running past the building and the fire’s reflecting their shadows, and I’m going, ‘My God, it looks like Goodyear after the night shift lets out. I live in this place, I live at the House of Pain, I live in the world of Doctor [Moreau].’ That was the epiphany, between that and the pamphlets, were the two main impetus for the song. “They tell us that we lost our tails, evolving up from little snails, I say it’s all just wind in sails, Are We Not Men? We Are DEVO!” It kind of became our theme song.

His laboratory is called the House of Pain and the animals are all afraid of it, because it is painful what he does to them to evolve them up. Most the experiments are all failed, so you see all these half-human, half-animals creeping around the outskirts of his compound. There was one that was fairly successful, a woman namedLota, who you find out was a tiger or something. These animals keep devolving, as much as he fights, using his technology and his expertise to evolve them up to full human status, they never quite get there, and most of them are failed, and they keep devolving back to the beasts they once were. He keeps them in control with a whip and a mantra, when they start acting crazy he cracks this whip and goes ‘What is the Law?’ and they all have to recite, ‘Not to walk on all fours, are we not men?’ ‘What is the Law’ ‘Not to shed blood, are we not men?’ I don’t know, just something about watching that on a 9-inch black-and-white set, late at night, that I had in my one-room apartment, and there;s this one scene where they rebel against him, and there is a fire in the jungle and it’s casting their shadows onto the House of Pain, and these disfigured sub-humans are trudging, waddling, running past the building and the fire’s reflecting their shadows, and I’m going, ‘My God, it looks like Goodyear after the night shift lets out. I live in this place, I live at the House of Pain, I live in the world of Doctor [Moreau].’ That was the epiphany, between that and the pamphlets, were the two main impetus for the song. “They tell us that we lost our tails, evolving up from little snails, I say it’s all just wind in sails, Are We Not Men? We Are DEVO!” It kind of became our theme song.

Phawker: I just put up a YouTube of you guys doing “Uncontrollable Urge” live, it might even be from Urgh! A Music War, but it’s amazing. I came of age during the dawn of MTV, so I knew you from all the real synthy early 80s stuff, and it wasn’t until recently that I realized what a great guitar-rock band you guys were in the beginning.

MM: Thank God for my brother Bob. I would have made us a soupy fizzy whizzy synth band long before. I was just kind of like, way out there, wanting to — I was damaged by John Cage. Luckily, I had my brother around who had a handle on of classic rock forms and, you knowm the essence of rock, because rather than just be purely an art band we had some huevos to us.

Phawker: Totally, you were kind of a party band as well.

MM: Yeah, it allowed us to function on a number of levels, as opposed to being a conceptual, elite, private joke. You could also get into Devo, even if the idea of de-evolution sounded totally absurd to you and you couldn’t give a shit about it and you just wanted to get out of the house, hear some music, and jump around and crash into people.

Phawker: But the music did become, later, almost exclusively synthy though.

MM: Well you know, it’s good that Devo was five people instead of one of us. That was kind of the lucky thing about having two sets of brothers, because it didn’t matter who got credit for writing a song because everybody contributed something to the writing of the song. It wasn’t like there was a Sting and two other guys in the band who did his bidding. We were really, like, a collaborative effort. And our best music was when we were really collaborative. I still like electronic music.

thing about having two sets of brothers, because it didn’t matter who got credit for writing a song because everybody contributed something to the writing of the song. It wasn’t like there was a Sting and two other guys in the band who did his bidding. We were really, like, a collaborative effort. And our best music was when we were really collaborative. I still like electronic music.

Phawker: Do you regret moving into that entirely electronic direction?

MM: No, what I regret is that there was an uneven shift — and I take blame for it — that there was an uneven shift in contribution between members of the band, in the latter albums. I actually like the latter albums a lot more now than I did then, when we were doing them. The last three albums were like science experiments that might have gone out of the lab a little too early. Like, Ambient or something, ya know just got out a little too early and a few people died or something.

Phawker: They sound very modern now, ironically enough.

MM: Well, they aged well, that’s the interesting thing. It’s like, when we play live these days, the stuff we choose to play incorporates more of the guitar stuff. We don’t play as many of the later albums, as we do from the early albums. Because that is when it was most enjoyable to be a part of Devo for all of us, in the early albums.

Phawker: I wanted to relate a quick story to you, that when I was in junior high school and “Whip It” was a hit, a couple of friends of mine were going to perform “Whip It” at the junior high school talent show, until the Powers That Be found out that the song was allegedly about masturbation and the kibosh was put on that.

MM: That’s hilarious.

Phawker: Yeah, they did “Turning Japanese” instead, which is amusing because that was also about masturbation, but the Powers That Be weren’t quite hip to the Vapors, I suppose.

MM: Well, “Whip It” wasn’t really about masturbation. Now this is the truth, “Whip It” was written because  we had just done two world tours, and the one thing people said was ‘We like American culture, but we hate your politics, and your President, he’s a puss. His foreign policy is terrible.’ At the time it was Jimmy Carter. We kinda wrote the song as, we were influenced by Dale Carnegie, “The Art of Selling,” from my father, who was like the ultimate optimist, who was like ‘I never met a man I couldn’t look in the eyes, shake his hand squarely, and work out a business deal by the end of the day.’ Winning Friends and Influencing People, Dale Carnegie, that’s it. The song was kind of — we thought of it as written for Jimmy Carter, as kind of a You Can Do It! You can say that sounds like the most ridiculous reason to write a song ever, but that was it.

we had just done two world tours, and the one thing people said was ‘We like American culture, but we hate your politics, and your President, he’s a puss. His foreign policy is terrible.’ At the time it was Jimmy Carter. We kinda wrote the song as, we were influenced by Dale Carnegie, “The Art of Selling,” from my father, who was like the ultimate optimist, who was like ‘I never met a man I couldn’t look in the eyes, shake his hand squarely, and work out a business deal by the end of the day.’ Winning Friends and Influencing People, Dale Carnegie, that’s it. The song was kind of — we thought of it as written for Jimmy Carter, as kind of a You Can Do It! You can say that sounds like the most ridiculous reason to write a song ever, but that was it.

Phawker: That’s the most ridiculous reason to write a song about masturbation, ever! Tell me when you first discovered Warhol? Was he largely an influence visually, or was it that he was holding up a mirror to America’s consumerist culture?

MM: That goes without saying. We saw ourselves as musical reporters, and we wanted to talk about things going on around, and that was our attraction to juxtaposing High and Low Art and High and Low Culture. Just a lot of it with Warhol was the fact that we thought he had the best job, he got to be a painter, he got be a photographer, he got to be a printmaker , he got to be a fashion designer, he got to be a magazine editor, he threw the best parties in Manhattan, he got to make films, and we thought ‘Ya know what, we’re not here just to be guitar players, we came from the fine arts world anyhow.’ We saw ourselves using technology, in the sense of using it to get our messages across. We didn’t even think of ourselves as a music band.

My parents just sent me a bunch of notebooks from the 60s and 70s where I would put ideas. When we talked about Devo, what we wanted to do, we thought of ourselves as a clearinghouse for art concepts. I think, rather than be a band that played onstage, our interest was to put together something that would be more like a Blue Man Group, mixed with re-education. A vitamin-enriched version of Blue Man Group, rather than just silly parlor games and silly music. We saw it as something that we wouldn’t even be the guys on stage, we would put together five or six Devos. We imagined five or six Devos out touring around the world, and it didn’t matter who the personnel were. It was even more progressive Menudo, rather than the concept of having one band where you changed the boys in it, they would be fellow artists who would go out and do the live performances.

and it didn’t matter who the personnel were. It was even more progressive Menudo, rather than the concept of having one band where you changed the boys in it, they would be fellow artists who would go out and do the live performances.

Phawker: What kept you from implementing this plan?

MM: Mostly money. And I think the blow that really locked us into being a band first, after we recorded our first album with Brian Eno and David Bowie, was we had three singles that were charting in Europe. And I remember saving a copy of Billboard that said Devo’s version of “Satisfaction” was number one in Yugoslavia, number 10 in Britain, and “Jocko Homo” was in the Top Ten in Scotland, which made me very happy that that could even happen. I just thought: Jocko MacHomo. I was thinking, “Who in the hell is buying this song to put it into the Top Ten in Scotland?” And “Mongoloid” was number one in France, and “Social Fools” was charting in Germany.

So a bidding frenzy happened, even though we didn’t have any jobs or apartments and we relied on girlfriends to let us crash in their apartments when we were back in Akron, so there were people like Chris Blackwell and Richard Branson flying over from Europe to sign us. Richard Branson had signed the Sex Pistols, who we thought was the most interesting pop band out at the time, and we met him. We got along, in a way, to the point where at one point, in kind of a foolish move on Branson’s part, he flew a couple of us to Jamaica to let us know he was with Johnny Rotten and Johnny Rotten wanted to join Devo . And we were like ‘Well we really like him but, ya know can we help out some other way, we don’t want him in our band. He needs his own band, he needs a corporate image of his own.’ Then the next thing he did was Public Image Limited.

Phawker: Wait, so he flew you guys down to the Caribbean? And Johnny Rotten was with him?

MM: He said ‘I have photographers and reporters from Melody Maker, Sounds, and the New Music Express, all here, and if you want, right now, we could go down to the beach and announce right now that Johnny Rotten has joined Devo.’ And unfortunately, they had given us so much pot to smoke during this meeting, that I was like, ‘Ya know what, I don’t even wanna play a joke right now’ because I was looking at Richard Branson’s mouth and I had never realized how protruding his teeth were, you know, he is the brain-eating ape that we talk about. My God, look at that! I remember looking at his mouth and looking at him staring at us and realizing that none of them were smoking the pot they had brought, and had handed to Bob and me. It became one of those moments in life, whether you’re either in church or at a funeral or you’re in school, and all the sudden the whole world seems imbecilic and you don’t want to laugh, but you can’t stop yourself because everything is ridiculous. I remember saying ‘Richard, I’m not laughing at you, I’m laughing because, it’s such a weird idea.’ I know that if I wasn’t smoking pot I would have been a big enough smart ass to go do it and then disavow it the next day.

Phawker: How did Johnny Rotten respond?

MM: Well, how can you respond if you fly down to Jamaica, and your band just broke up, and I don’t think Sid was even dead yet. It all happened really fast, and we had met them when they were playing their last show in San Francisco, because we were playing Mabuhay Gardens at the same time. We played the night before and the night after and then they played and came over hung out with us. Sid Vicious was cute, he and Nancy, they would do stuff, like we were at this house that belonged to one of the editors of Search and Destroy magazine, cause we didn’t have any place to stay, so let us sleep on the copies of the magazine that hadn’t been sent out yet. I remember Sid and Nancy would like inch a beer bottle until it fell off and broke, and they’d both look around to see who would be upset about it, and no one gave a shit. He did it for awhile and got kinda bummed that no one got upset.

Phawker: It’s a good metaphor for the life of Sid, actually. Let me jump ahead here, what was the end of Devo version one?

MM: The funny thing is, we always made money for Warner Bros., every record was in the black, we sold enough hundreds of thousands of records that they made lots of money. Kind of the downfall with Warner Bros. was the album Freedom of Choice, because “Whip It” accidentally became a hit, and then they paid attention to us. They’d show up at the recording studio and be like ‘Hey guys, do whatever you want, just make sure there’s another “Whip It”!” and they’d look and they’d go ‘This doesn’t sound like “Whip It!”  Nothing sounds like “Whip It!” We had this song we had done called “Working in a Coal Mine,” it was Lee Dorsey, it was our cover version, and they were like ‘No no, this can’t go on the record, you can’t put this on the record’ and we go ‘Why?’ there were like ‘Hey Kids, lets put something together that sounds more like “Whip It!”‘ and we had nothing else, so they took it off and put something else on. So we had this song, called “Working in a Coal Mine” and we get this call from these people making a movie called Heavy Metal, and they said, ‘Well, we got this band that’s playing in this outer space bar, that is frequented by criminals and odd characters and it’s kind of like the Wild West but wilder, because it’s outer space, and we want the house band to be some mutated version of Devo, do you have a song for it?’ so we gave them “Working in a Coal Mine.” But wouldn’t ya know, we thought we were gonna get a free ride, because it’s the movie Heavy Metal, so they’re gonna put all these heavy metal bands, like Sammy Hagar, all these people are putting songs on it, they sell a lot more records than us, we’re gonna get a free ride on this one. We thought we were being subversive by putting a song on the movie Heavy Metal. The joke was on us, because our song was the only one that went into the Top Ten, and it happened right as Warner’s was gonna release the album that they had removed the song from, so they had a super panic attack and didn’t know what to do, so they included it as a free flexi-disc in the albums, because they didn’t know what to do. It was all set to go out, so they had to put stickers on it that said: Includes single “Working in a Coal Mine!” It totally fucked up any other campaigns for promoting a single, it was totally pathetic. So we had had our fill with them.

Nothing sounds like “Whip It!” We had this song we had done called “Working in a Coal Mine,” it was Lee Dorsey, it was our cover version, and they were like ‘No no, this can’t go on the record, you can’t put this on the record’ and we go ‘Why?’ there were like ‘Hey Kids, lets put something together that sounds more like “Whip It!”‘ and we had nothing else, so they took it off and put something else on. So we had this song, called “Working in a Coal Mine” and we get this call from these people making a movie called Heavy Metal, and they said, ‘Well, we got this band that’s playing in this outer space bar, that is frequented by criminals and odd characters and it’s kind of like the Wild West but wilder, because it’s outer space, and we want the house band to be some mutated version of Devo, do you have a song for it?’ so we gave them “Working in a Coal Mine.” But wouldn’t ya know, we thought we were gonna get a free ride, because it’s the movie Heavy Metal, so they’re gonna put all these heavy metal bands, like Sammy Hagar, all these people are putting songs on it, they sell a lot more records than us, we’re gonna get a free ride on this one. We thought we were being subversive by putting a song on the movie Heavy Metal. The joke was on us, because our song was the only one that went into the Top Ten, and it happened right as Warner’s was gonna release the album that they had removed the song from, so they had a super panic attack and didn’t know what to do, so they included it as a free flexi-disc in the albums, because they didn’t know what to do. It was all set to go out, so they had to put stickers on it that said: Includes single “Working in a Coal Mine!” It totally fucked up any other campaigns for promoting a single, it was totally pathetic. So we had had our fill with them.

Phawker: What album was that?

MM: That was New Traditionalists. So we did one more album with them, and then we had been talked to by this guy, who we had known, before who had a company called Green World, they were one of the early importing companies. It was these three well-meaning hippies, who paid attention to all the music that was out there and they knew that the chains of the time were not paying attention to the really cool music of the time. The name was an homage to Brian Eno, and they started a record company. They accidentally — we didn’t know it was accidental we thought they were geniuses — signed a band called Stryper , the Christian rock band. They signed them right at the time Christians were saying ‘By God we need something to counteract all this evil music our kids are hearing here in River City, there’s a pool hall and we need a Christian pool hall,’ so, here ya go, Stryper. So they sold a ton of Stryper records and made a lot of money, and they were being predicted to be the next A&M Records. So Bill Heim came and said you guys want to sign with our record company, and we said yeah these guys will understand us. But by the time we signed with them, we walked in the next day to the record company and realized we had signed on to the Titanic. They were sinking, they couldn’t duplicate their success with Stryper with any other kind of bands, so there were all these bands like Mojo Nixon and the Dead Milkmen, and all these interesting bands, we were all trapped on the same sinking ship. We did a few records with them, but it was, at that point, a lot of the spirit had been . . . there was dissent within the ranks, and we did these more electronic albums, because nobody was showing up when it was time to write music.

spirit had been . . . there was dissent within the ranks, and we did these more electronic albums, because nobody was showing up when it was time to write music.

Phawker: Does that mean it deferred to you?

MM: Yeah, I have to take responsibility for the music, I didn’t have a full band to work with anymore. And we eventually went into cocoon, siesta, hibernation mode. We never broke up, we just kind of shriveled up, and stopped doing what we were doing. It was like, the mud puppies in the African River when there’s no more water left in the stream, they’re just locked in the mud and nothing new is happening, but they aren’t dead, but they’re not alive either.

Phawker: This about what year, would you say?

MM: Around ’85 or ’88. It’s all kind of weird, somewhere in there a friend of mine had said “I’m doing a show at the Roxy, it’s a character I invented called Pee Wee Herman, can you do the music?” I said I can’t because I was on tour with Devo. He said “Hey I got a feature film, do you wanna score it?” I said I’m gonna be in Europe the entire time you need me here. So then he said, “I got a TV show now, would you?” And I go, “I’d love to.”

Phawker: And so that was the beginning of Mark Mothersbaugh, soundtrack man’

MM: Going into TV, yeah.

Phawker: Which I’m guessing is far more lucrative than Devo?

MM: Well, it was satisfying artistically in the sense that, we had gotten to a point where it would take a year to write 12 songs, ya know? Getting them ready for an album, making a video, and then going on tour and singing the same songs, so this was something where I had to write the same amount of music each week for this show. So it was like, ‘Well I’m gonna come back and sing this next week, when my voice will sound different and maybe we can mix with a different melody.’ Instead, you had one shot to do it and you’re watching the clock so that you could get it to FedEx in time to get it to New York. I would get it on a Monday, watch it and write on Tuesday, record it on Wednesday and Thursday, then send it out Thursday night. Friday it would be watched by censors and Saturday we’re watching it on TV. I like this. [Meanwhile, our record company] Warner Bros. was in Burbank and we were in Hollywood, yet for some reason they could never get us the check, something would always happen.

MM: Well, it was satisfying artistically in the sense that, we had gotten to a point where it would take a year to write 12 songs, ya know? Getting them ready for an album, making a video, and then going on tour and singing the same songs, so this was something where I had to write the same amount of music each week for this show. So it was like, ‘Well I’m gonna come back and sing this next week, when my voice will sound different and maybe we can mix with a different melody.’ Instead, you had one shot to do it and you’re watching the clock so that you could get it to FedEx in time to get it to New York. I would get it on a Monday, watch it and write on Tuesday, record it on Wednesday and Thursday, then send it out Thursday night. Friday it would be watched by censors and Saturday we’re watching it on TV. I like this. [Meanwhile, our record company] Warner Bros. was in Burbank and we were in Hollywood, yet for some reason they could never get us the check, something would always happen.

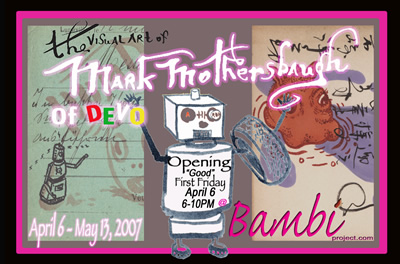

Phawker: Tell me about the postcard project, and I don’t know if you aware of this, but you’re showing in a gallery in Philadelphia that is, basically, the little guy on the block. Gal, to be exact.

MM: Yeah, you know what, that is not an accident. I was getting most of my support from Juxtapoz magazine galleries, and the readers of Juxtapoz, and the people who wanted to show with me were graffiti artists. So, I went to Juxtapoz and looked for all the little ads in the back, and that’s how I got started. Now, I’ve been to about 75 different galleries across the country, actually a hundred or so around the world, although I sometimes do bigger, more legitimate galleries, it was actually aimed at ones where people were still younger and hungry. We kind of have a symbiotic relationship, as I get connected with street people, who are maybe looking at art as a possibility to buy for the first time, and so I’m selling my stuff as cheap as I can. And there places that are of little reputation, but they are able to get someone like you interested enough to do an interview for something. SO it works out good for both of us. I think I’ll always want to show at smaller galleries, just ’cause I enjoy them more. I go into small galleries and I find people that are still excited about the process of making and showing art. It’s not like the galleries where they’re looking for bankers, lawyers, and doctors to invest for long-term market strategy. These are people who come in and if they like something go ‘Shit, I like that!’ then they buy it and put it on the wall. So I try to make it cheap enough so that the worst they’re giving up is being able to throw one party or something.

people who come in and if they like something go ‘Shit, I like that!’ then they buy it and put it on the wall. So I try to make it cheap enough so that the worst they’re giving up is being able to throw one party or something.

Phawker: Any impression or memories of Philadelphia?

MM: Yeah, the funniest one, well we got to play Tower, which is a great place, at the Tower I had good experiences. I found a suit that belonged to Spike Jones, and Booji Boy wore it out on stage to sing. It was almost like a zoot suit, but it was green with these silver stripes that went both ways, and it said Spike Jones on the collar. But I was never really sure, until I got to Philly and there was a picture on the wall of Spike wearing the exact suit.

The second is we played the Hot Club the first time we played in Philly, around 1977. While we were taking our equipment into the place, we had two rickety cars that loaded the trunk up with amplifiers and drums. While we’re taking the stuff in, somebody walked by and stole all of our crew guy’s clothes, that were on coat-hangers inside the car, so he had to be filthy for the weekend. But, the Hot Club, to show their appreciation, bought us dinner and at midnight they had a stripper come, with some bearskin rug that she set on the stage we had just played. So we had Philly steak sandwiches to eat while she stripped. That’s my two best stories.