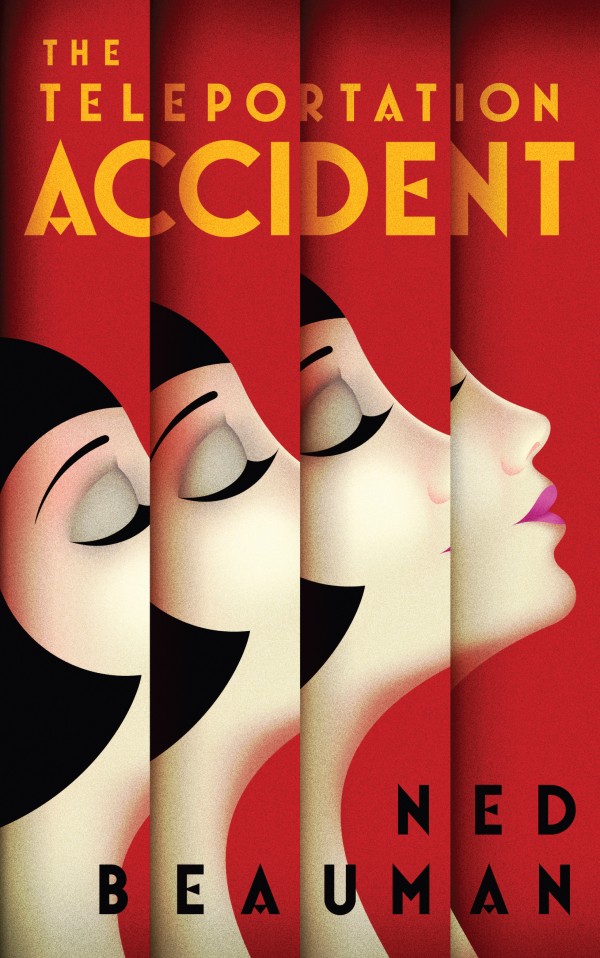

BY BRANDON LAFVING UK-based author Ned Beauman reaffirmed his position as “Most Likely To Be The Victim Of Homicidal Jealousy Of Male Writer Aspirants” last month when Bloomsbury published, The Teleportation Accident. This is the 27-year-old Beauman’s second novel to receive thunderous and near-universal accolades — the first being 2010’s Boxer, Beetle — and much as I’d love to call ‘bullshit’ after reading The Teleportation Accident I must resignedly admit to knowing what the hype is about.

BY BRANDON LAFVING UK-based author Ned Beauman reaffirmed his position as “Most Likely To Be The Victim Of Homicidal Jealousy Of Male Writer Aspirants” last month when Bloomsbury published, The Teleportation Accident. This is the 27-year-old Beauman’s second novel to receive thunderous and near-universal accolades — the first being 2010’s Boxer, Beetle — and much as I’d love to call ‘bullshit’ after reading The Teleportation Accident I must resignedly admit to knowing what the hype is about.

Our picaresque and highly unlikely story opens in Berlin circa 1931 with Egon Loeser, a bohemian anti-hero/playwright too smart for his own good and obsessively focused on exactly two things: his work and his pursuit of women. Neither is going well. As admitted by the narrator, himself, “…the establishment of a global Marxist workers’ paradise seemed a modest and plausible aim in comparison to this ludicrously optimistic vision of a world in which he, Egon Loeser, actually got close to a non-mercenary vulva once in a while.” In fact, Mr. Loeser spends years without getting laid. This would make the novel tragic except for the fact that he deserves it. So instead of inducing pity, his Saharan dry spell comes across as cathartic and quite funny.

Neurotic and derisively arrogant, Loeser is a stage designer who is attempting to recreate The Teleportation Device –a fabled mechanism that effortlessly changes your geographic location without human aid or effort, which was originally designed for theatrical applications back in 1679. The Device automatically changed  the stage set without human aid or effort. But in the second act of its debut, the device came undone, taking with it the secret to the mystery of its construction, as well as a number of lives in one of the most grandiose and implausible calamities of Beauman’s fictive Europe. When Loeser’s own play is canceled, robbing him of a reason for reproducing the Teleportation Device, leaving him with only one desire: women. leaving him without means of reproducing the master work and only the second half of his obsessive desire: women. a fabled mechanism that effortlessly changes your geographic location without human aid or effort. In the second act of its debut in 1679, the Device had come undone, taking with it the secret to the mystery of its construction, as well as a number of lives in one of the most grandiose and implausible calamities of fictive Berlin. In another sadistic twist of fate, Mr. Loeser’s play is canceled, which leaves him with nothing but his unrequited obsession with women.

the stage set without human aid or effort. But in the second act of its debut, the device came undone, taking with it the secret to the mystery of its construction, as well as a number of lives in one of the most grandiose and implausible calamities of Beauman’s fictive Europe. When Loeser’s own play is canceled, robbing him of a reason for reproducing the Teleportation Device, leaving him with only one desire: women. leaving him without means of reproducing the master work and only the second half of his obsessive desire: women. a fabled mechanism that effortlessly changes your geographic location without human aid or effort. In the second act of its debut in 1679, the Device had come undone, taking with it the secret to the mystery of its construction, as well as a number of lives in one of the most grandiose and implausible calamities of fictive Berlin. In another sadistic twist of fate, Mr. Loeser’s play is canceled, which leaves him with nothing but his unrequited obsession with women.

You might think that anyone living in 1931 Germany would consider the dramatically shifting political situation with a certain degree of import — Weimar Berlin was falling and being replaced by the Nazi rise to power — but next to women, these historical factoids are almost totally eclipsed. Egon’s understanding of the political turmoil, rather than being grounded in fact, is realized peripherally. The name Hitler is indeed familiar, but Adolf is “…the other Hitler,” to our hero, who is infatuated with Adele – a beautiful, salacious, blond-haired woman with the same last name as der Fuher. With no work to occupy his time, Loeser chases Adele to Paris and then the United States. Completely incidental to his quest for satisfaction are the clues leading him to solve the mystery of the Teleportation Device accident in the days of yore.

On the first leg of the tale, Beauman constructs a bohemian world that serves as pithy reminder of our own. Perhaps the funniest of these slanted references comes in the form of drug choice. When he first discovers people have started taking the animal tranquilizer, ketamine, instead of cocaine, he depicts the scene with, “It was one of those country parties where it felt as if no matter where you went you were always being watched by either a live horse or a dead stag, until you found yourself lingering by the washbasin after a piss just to escape this weirdly oppressive ungulate panopticon.” What is perhaps even scarier than the similarities between Nazis and the effects of ketamine – the depiction of 1930s Berlin was lifted from Beauman’s own experience of East London in 2009, which he all but admitted in an interview with GQ-Berlin.)

The novel’s plot points are sometimes incredibly poignant, as in the details above, but they can also come off as haphazard, neurotic, or even contrived. This is particularly true once you get past the halfway point, and Loeser chases Adele to Los Angeles as the novel undergoes a sea change jerking the reader from speculative historic fiction into a suspense-thriller parody. There is intrigue, romance, a series of homicides, an opportunity to get the girl, and so on. Because I don’t read a lot of suspense/thriller novels, I may have missed some of the jokes during this portion, but in my case, the comic relief fell a little flat. It is all tied up nicely though in the end, and like on a date where both parties discover they do not see eye to eye on politics but nonetheless still want to sleep with each other, I barely remembered my earlier qualms or even cared by the end.

The Teleportation Accident is an incredibly witty and elaborate work – full of self-derision, delusions of grandeur and idiosyncrasy. Even better, it is experimental and takes risks – risks that may not capitalize in the novel, itself, but will most likely support the longevity of Mr. Beauman’s career as a novelist. He is someone you want to get on board with now, if only so that you can tell your friends you found him first.