BY JEFF DEENEY As a little boy in the late ’70s I lived with my family on 63rd Street in Overbrook in the row home attached to my grandparents’ row home. I never knew my Irish grandparents on my father’s side; their lives were cut short by ill health and alcoholism when my father was a teenager, leaving him and his four older siblings to fend for themselves. But my grandparents on my mother’s side were ever-present, their tiny house a hub of activity on the block where they had spent much of their lives since getting off a boat from Italy. While I sat on their plastic covered couch watching TV a host of characters floated in and out; the door was always open and my grandmother was always cooking something to feed whoever showed up.

BY JEFF DEENEY As a little boy in the late ’70s I lived with my family on 63rd Street in Overbrook in the row home attached to my grandparents’ row home. I never knew my Irish grandparents on my father’s side; their lives were cut short by ill health and alcoholism when my father was a teenager, leaving him and his four older siblings to fend for themselves. But my grandparents on my mother’s side were ever-present, their tiny house a hub of activity on the block where they had spent much of their lives since getting off a boat from Italy. While I sat on their plastic covered couch watching TV a host of characters floated in and out; the door was always open and my grandmother was always cooking something to feed whoever showed up.

Everyone seemed to be identified by their ethnicity; it was just how everyone knew everyone else back then. There was Mary the Polack, Rose the Armenian, and so on. And when I say the neighborhood was full of characters, I mean it. For instance, there was Vince the Prophet, a wild looking old Italian guy with scraggly hair and a long beard who walked around the neighborhood in nothing but a set of short-shorts year-round talking to himself. Some said Vince was mentally ill, others said he was a poet, but in such an intensely Catholic neighborhood he eventually took on the reputation of a holy fool, touched by God; Overbrook’s own Reeking Lizaveta.

Then there were “the blacks”. My God, when was anyone ever not talking about “the blacks”? Around the kitchen table my grandmother and the other ancient local crones would talk forever — over strong coffee that she roasted and ground herself — about the blacks. By the late ‘70s white flight had already drained many Philly neighborhoods and Overbrook’s time was long overdue. As whites left, real estate prices plunged, rents went down and black families came from places like the neighboring Black Bottom where 1960s redevelopment had demolished housing and disenfranchised communities.

Sure, the neighborhood had gotten worse. In fact, by the time my family left for Delaware County it was downright dangerous. One of my earliest childhood memories is of watching an elderly Italian woman walking on Haverford Avenue getting  mugged by two black teens. One of the boys came from behind and grabbed her around the waist, lifting her in the air. The other boy then snatched the purse she was holding and made off with it, as his accomplice slammed the old lady to the ground and fled along with him. I was in the back seat of the family car, and my father, a Navy veteran and labor-hardened tradesman known to be a bit hot-tempered, screeched to a halt, threw his door open and then ran off after the two kids. About five minutes later he came back – with the purse. He had run the two kids down and probably administered a beatdown. He dusted the old lady off and sent her on her way.

mugged by two black teens. One of the boys came from behind and grabbed her around the waist, lifting her in the air. The other boy then snatched the purse she was holding and made off with it, as his accomplice slammed the old lady to the ground and fled along with him. I was in the back seat of the family car, and my father, a Navy veteran and labor-hardened tradesman known to be a bit hot-tempered, screeched to a halt, threw his door open and then ran off after the two kids. About five minutes later he came back – with the purse. He had run the two kids down and probably administered a beatdown. He dusted the old lady off and sent her on her way.

You can imagine around the coffee table later that afternoon, with all the neighborhood oldsters gathered to hear him tell the heroic tale, how it became another sprawling and heated conversation about “the blacks.”

That wasn’t the only incident. Like “John” the old man who lives on Woodstock Street in Fairmount in Philadelphia Magazine’s thoroughly pilloried Being White in Philly story, my grandparents as they aged were repeatedly targeted for crime. I remember sitting in their living room as they arrived home from their annual trip to Italy and a family meeting came to order as they walked through the door so my parents and aunts and uncles could explain that while they were gone the house had been looted. I remember their confusion, asking in their broken English, “Us? Robbed? Who would this? Why would they do this?” Yet they refused to move, as much as my parents implored them to follow us to the suburbs. They insisted that despite everything they would die on 63rd Street, they wouldn’t be run off. A few years later, they did die, and my connection to Overbrook would be severed for years to come, until I would eventually return there as a social worker three decades later.

In the intervening years, the voices in my life decrying “the blacks” and how they ruined Philadelphia would only grow louder. Delaware County is full of Baby Boomer West Philadelphia expatriates who love nothing more than to gather and tell tales about how great their old neighborhoods were before “the blacks” came, and how sad it is that “the blacks” ruined them, forcing them to move the suburbs. As a kid I didn’t challenge these voices, though my cognitive dissonance alarm began ringing when I found that my relatively few black classmates weren’t mean, they didn’t steal, and they didn’t bully other kids. I saw my white classmates doing these things all the time, but they weren’t saddled with the ‘bad seeds’ stigma shouldered by black kids who didn’t.

I remember when I was maybe 11-years-old a white gym teacher pulling a black kid to the front of the gymnasium so he could address him in front of the entire class. We had just taken the Presidential Physical Fitness test, and while this kid’s 100 yard dash time was extremely good, the teacher was surprised to find it wasn’t better.

“With all that running from the cops you do, this is your best time? How are you going to stay out of jail if this is the fastest you can run? You need to improve your time, son, or else you’re going to wind up doing time.”

I remember feeling knots in my stomach while many of my classmates laughed along with the teacher. I still didn’t have a clear idea of what racism was, but I knew something about this was deeply wrong. But as a child, what do you do? Go home and  talk to your parents about it? They would support the teacher, assuring you that you would too if you had walked in their shoes, through the old neighborhood, suffering criminal indignities at the hands of “the blacks.” The gym teacher had probably been mugged before, and just knew better, they’d say. So I didn’t speak up about racism, but I was constantly, relentlessly barraged by it.

talk to your parents about it? They would support the teacher, assuring you that you would too if you had walked in their shoes, through the old neighborhood, suffering criminal indignities at the hands of “the blacks.” The gym teacher had probably been mugged before, and just knew better, they’d say. So I didn’t speak up about racism, but I was constantly, relentlessly barraged by it.

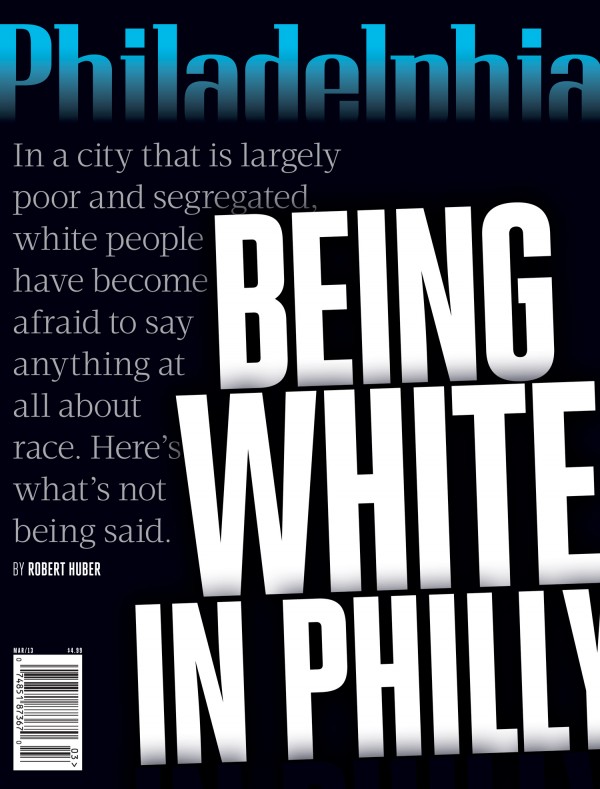

Putting all the other criticisms I could possibly make aside, this was the main problem I had with Philly Mag’s story, whose central contention is that whites are afraid to talk about how blacks have wrecked this city with their criminality and irresponsibility. Those of us who grew up in working class Philadelphia can assure you that white people in Philly have no problem talking about race. Some of us spent our formative years drowning in aggrieved white voices and had to struggle to pull ourselves above the prejudices that the generation ahead of us tried desperately to hammer into us.

For me it all came to a head in what became known in family lore as the Columbia Incident. At some point a teacher clued my parents into the fact that not only was I not going to go to a vocational-technical school like my dad and older brother had, I was going to go to college and possibly an elite one, at that. In a rush to catch up with the other college bound kids we started visiting college open houses, and Columbia University’s was, not surprisingly, held at Radnor High School on the Main Line. With a packed house of boat shoe-clad bluebloods, the Columbia rep held forth on the university’s storied reputation as an academic powerhouse and producer of world leaders. After giving her spiel she opened up the floor to questions and I remember actually stopping breathing when my dad’s hand immediately flew into the air. Oh my God, I thought, Oh my God, NO!

Needless to say the Deeney family already stood out. I grew up a working class Delco metalhead whose childhood friends were more likely to overdose or do time than go to Columbia and I looked the part, sitting awkwardly in Radnor’s library in beat up basketball sneakers and a Slayer t-shirt. My gun nut dad, no shit, was wearing a camouflage sweatshirt with an 8 point buck on it. The Columbia rep called on my dad and with the whole room already giving us massive side-eye he asked, “So how far away from Harlem is this place?”

That’s his question. After hearing about Columbia’s history and academics and all it has to offer his kid, that’s the first and really only thing my dad wants to know: how close is Columbia’s campus to “the blacks”?

As I searched around in vain for a gasoline canister and a lighter that I could use to set myself on fire in order to escape the barrage of boos and hisses that followed, I knew this was the breaking point.

During the ensuing screaming match on the drive home my dad first swore up and down that he was asking a geographical question, trying to orient his view of the campus in his mind’s eye by using Harlem as a landmark. After pointing out to him that he couldn’t find Harlem on a map of Manhattan if his life depended on it, he ultimately fell back on his old standby argument. Those Columbia parent types are a bunch of Main Line sissies who don’t know shit about the real world. They didn’t grow up in West Philly. They had never been held up at gunpoint, like he had. They’re sitting in the blissful liberal ignorance that the lap of luxury affords them pointing fingers at him for being nothing more than an honest realist.

My father really was a loveable man, despite the impression you may have from what’s said here, and I did love him deeply. He did hard labor his entire life to feed and house his family and eventually pay for me to go to one of those elite universities. Due to cancer, he died young; he never got to enjoy retirement. But despite the gratitude I may have for the things he worked so hard to give me it doesn’t change the fact that he was also deeply, thoroughly, loudly and insistently wrong about race, and the fact that I refused to join him in ignorance and prejudice vexed him to no end. For years after the Columbia Incident, until the day he died, we engaged in one ugly battle after the next about racism.

My father never had any problem expressing himself on sensitive issues; frankly, the idea that the voices of white people in Philadelphia expressing racial grievance aren’t getting amplified loudly enough is patently delusional. White people in my father’s generation and like-minded types, men particularly, in generations behind them dominate Internet conversation on race the same way they dominate every conversation they have, ever. Philadelphia like every other major city desperately needs a broader representation of voices in its media landscape; more women’s voices, more queer voices, more black, Latino and Asian voices. The fact that Philadelphia is so poor, and so black and so stacked with so many challenges particularly affecting poor neighborhoods only accentuates the immediate need for a leveling of the media playing field so that the honest dialog the Philly Mag story purports to kick off can actually happen.

There’s a lot of anger going around this city right now because of a magazine story that is almost universally agreed to be completely irresponsible. However, if you’re on the fence, let me beg you not to be taken in by it. Reject it. Don’t listen to old white men who are disengaged from reality, steeped in fear and delusional prejudice and as a result draw the same wrong conclusions for all the same reasons my father always did.

There are thousands of people in Philadelphia who have rejected the racist notions their white families tried to instill in them, who every morning put their boots on, pick up their shovels and get to the hard work of change. We are social workers, teachers, doctors, lawyers, advocates, urbanists and activists. Please join us; there is so much to be done. Nobody argues this much; the damage done to our city by the generations that came ahead of us, who have stripped the economy and our budgets to the bone, letting our neighborhoods lapse into deep segregation and epidemic violence while pointing accusatory fingers from a distance, is extremely severe. Right now, today, this moment, it is being acutely felt by the most vulnerable among us. You can take Philadelphia Magazine’s lead, and selfishly retreat from our problems, or you can muster the actual courage necessary to dive headlong into them. Forty years from now I don’t want to be sitting in a suburban cul de sac blaming somebody else for what happened to my city, I want to be living in a better city that is better for the hard work I put into making it that way, and so can you.

RELATED: Being White In Philly

RELATED: City Paper’s Daniel Denvir on “Being White In Philly” Article

RELATED: Philly Mag’s Jason Fagone on “Being White In Philly” Article

RELATED: Philly Mag’s Steve Volk On Why He Hopes You Won’t Read “Being White In Philly” Article

RELATED: Atlantic’s Ta-Hahisi Coates On Why He’s Against ‘The Conversation On Race’