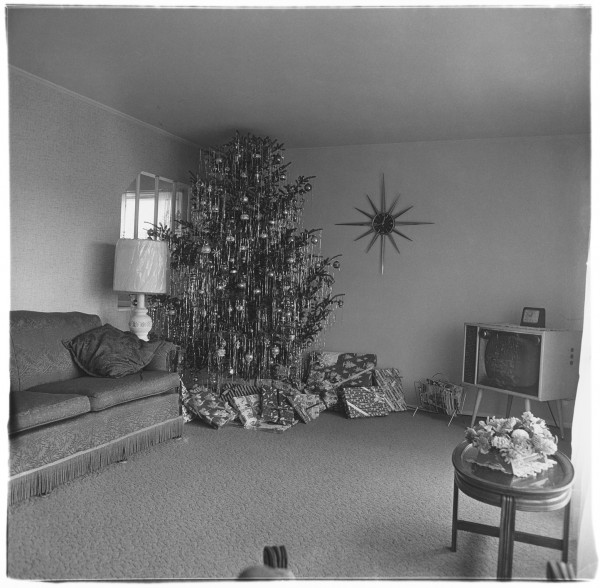

Photograph by DIANE ARBUS

BY JIM KNIPFEL Lord knows what happened to me — or what happened to most of us, for that matter — along the way. When you’re a kid growing up in the snowy Midwestern suburbs, you simply have no choice–Christmas is a magical time whether you want it to be or not. I mean, I was a reasonably normal kid. No, that’s not true. I had a reasonably normal family. No, that’s not exactly true either. We did reasonably normal, holiday-type things around Christmas. That’s true. My folks would take me to see Santa at the local department store, then they’d take me to see him at the bank, then they’d take me to see him at the gas station (I’m not sure why, but Green Bay regularly installed Santas in banks and gas stations), all on the same day. I never asked how Santa could be in all those places at the same time. I never doubted that they were all the real McCoy, either. I just figured he was following me around.

BY JIM KNIPFEL Lord knows what happened to me — or what happened to most of us, for that matter — along the way. When you’re a kid growing up in the snowy Midwestern suburbs, you simply have no choice–Christmas is a magical time whether you want it to be or not. I mean, I was a reasonably normal kid. No, that’s not true. I had a reasonably normal family. No, that’s not exactly true either. We did reasonably normal, holiday-type things around Christmas. That’s true. My folks would take me to see Santa at the local department store, then they’d take me to see him at the bank, then they’d take me to see him at the gas station (I’m not sure why, but Green Bay regularly installed Santas in banks and gas stations), all on the same day. I never asked how Santa could be in all those places at the same time. I never doubted that they were all the real McCoy, either. I just figured he was following me around.

We’d decorate the tree (no question that it had to be a real one) a week beforehand while listening to the Beatles’ White Album. We hung stockings. I kept trying to build snowmen, but they always ended up looking like they had cystic fibrosis. Every year — for awhile, at least — my Dad and I would set up elaborate Rube Goldberg devices just before I went to bed to try and steal a photograph of Santa. They never quite worked, but I guess I never really expected them to.

Things started to change when I was 11 or 12. It was right around then that my first major depression grabbed hold, when I first started growing bitter and cynical and world-weary. I like to think of it as when I first started thinking. All the magic vanished. December became an insufferable month, and I imagine I became a pretty insufferable kid along with it.

I was working my first job then, doing undercover security in a candle shop in a local shopping mall. Every weekend from Thanksgiving through the first of the year, it was my job to simply walk into the store when the doors opened, then hang out there until they closed, wandering around and around and around, pretending to be a customer, sweating like a little piglet in my down jacket, keeping an already weak eye out for shoplifters.

Maybe that’s what did it to me. My head screaming from the inescapable sweet stench of those fucking scented candles; realizing that my first job required that I be a rat (even though I never caught anybody), and, worst of all, my first close contact with a holiday-mad public. Up until that time, my folks had very wisely kept me away from all that. Actually, I think they kept me away from crowds in general because I had a nasty tendency to grab hold of strangers’ hands and wander away with them.

Nevertheless, it was in that candle shop that I first saw the pinched, bitter, evil, twisted face of the “holiday shopper.”

People keep trying to explain away holiday cynicism by saying that Christmas is a time for kids. There’s certainly some truth in that — but not enough of it. I mean, kid or not, everybody comes into the season wanting something. Everybody’s expecting something, whether it’s delivered by some fat elf or some fat aunt.

It’s not my point here to go on about holiday greed. I don’t give a good goddamn about holiday greed. I don’t care about over-commercialization either. This is America, and if we’re going to have a holiday, I think the only way to handle it is to over-commercialize it. What really struck me about the shoppers who crammed into the candle shop wasn’t so much the greed or overweening consumerism in their eyes, but the fear. They were scared to death of what they couldn’t give and what they couldn’t get. They were terrified of not stacking up when the final totals rang. I pitied their fear, their panic, and decided that it was about time that I separated myself from the whole filthy mess.

This isn’t the easiest thing to do when you’re a kid. More is expected of you then: more smiles, more glee, more eyes sparkling with wonder. You get sent away to a youth home if you don’t deliver. So I wasn’t able to truly escape Christmas until I moved out East, and even then it took awhile.

When Laura and I were still living together, we’d at least do a little bit of something. We give it a bit of a go. Put red and green candles on the table, prop an evil-looking Santa up on the mantle. Splurge when we couldn’t afford to and pick up a case or two of cheap wine. We even had a little fake tree that we’d decorate. Since the cats had too much fun knocking it over, we couldn’t leave it on the floor, so we ended up hanging it from the ceiling. The beasts couldn’t knock it over anymore, but they could still rear up and bash it around. What we had done, I guess, was turn it into a kind of Christmas pinata.

Now that I’m alone, the tree remains stuffed in a cardboard box, jammed up into the back corner of a closet in the hallway outside the apartment. While I used to play the wacky cowboy Christmas tunes of Tex Johnson and his Six-Shooters on the stereo, now the closest I get to having any holiday music play in the apartment, on my own time, is when Stan Rogers sings “First Christmas Away From Home”: (“Three thousand miles away, now he’s working Christmas Day/ Making double time for the minding of the store…”). Come to think of it, I guess I do make a point of pulling that tape out every year and playing it, just to wallow in a big vat of boiling holiday misery. I’m pretty cheap that way. The closest I get to expressing anything close to the Christmas spirit is sitting back at work and watching the twinkly little red lights sparkle across my central command telephone system.

That’s not very Christmas-y, I guess, but I guess it’s better than shooting elves.

When you live alone, and your family’s a thousand miles away, and you’re a blind, suicidal sonofabitch to boot, the whole Christmas season tends to lose a little something once you get off the brightly decorated streets and into your own shadowy apartment. Or at least my shadowy apartment. I think that attempting to fill my little room with holiday cheer would be even sadder and more grim than just leaving it alone. I mean, nobody’s going to see it, and in a few weeks, I’d just have to pack it all away again, admitting that it was all just a big mistake.

Now, to be honest, I have accepted an invitation to a party on Christmas Eve. The way I’m looking at it, though, it’s just a chance to get together with some folks I like, some of whom I don’t get a chance to see very often. When I leave the party, it’ll be back to the lonely Christmas Eve subway, back into Brooklyn with the rest of the losers, back to my apartment where I’ll crawl into bed with the cats, same as I do every other night. The next morning, even though it’s a Monday, will be like any Sunday. I’ll eat cold cereal for breakfast. It’s not like I’ll have a mountain of presents to wade through. Maybe I’ll watch a movie. Maybe I’ll get drunk. To be honest, I’ll probably end up doing both. I’ll shuffle around, I’ll smoke cigarettes, I’ll look out my window, and it won’t mean a damn thing to me.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Jim Knipfel is an American novelist, autobiographer, and journalist. A native of Wisconsin, Knipfel, who suffers from retinitis pigmentosa, is the author of a series of critically acclaimed memoirs, Slackjaw, Quitting the Nairobi Trio, and Ruining It for Everybody, as well as two novels, The Buzzing and Noogie’s Time to Shine. This piece originally ran in the New York Press in 1995.

PREVIOUSLY: Q&A With Jim Knipfel, Ex-Slackjawed Local