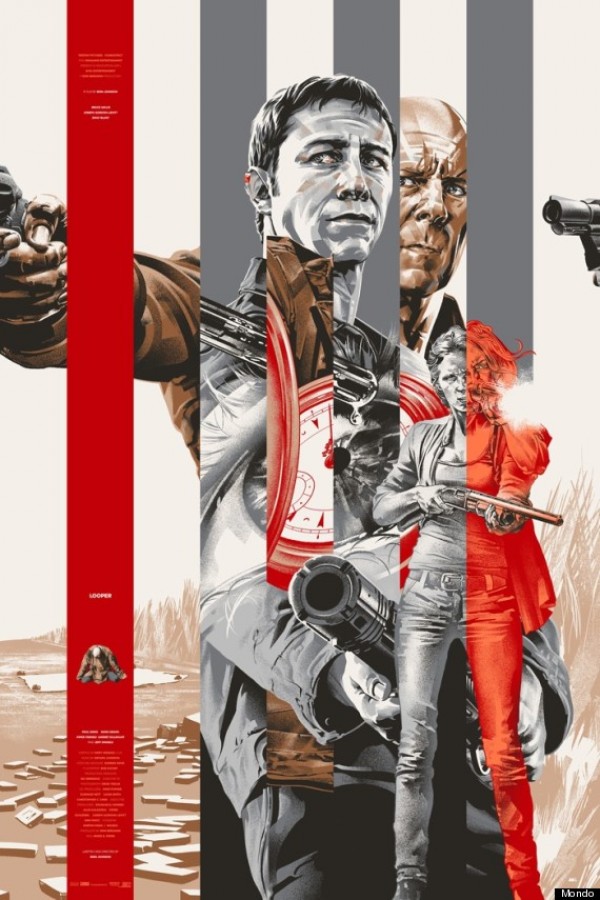

Artwork by MARTIN ANSIN

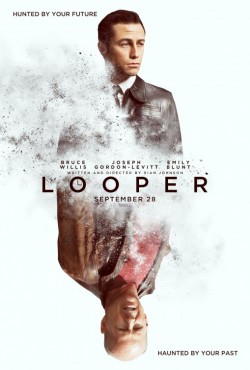

LOOPER (2012, directed by Rian Johnson, 118 minutes, U.S.)

BY DAN BUSKIRK FILM CRITIC Looper, the new sci-fi film by writer/director Rian Johnson (Brick, The Brothers Bloom) starts out with a fatal unforced error. It’s the make-up applied to the eyes, nose, and jaw of its star Joseph Gordon-Levitt, a ham-fisted stab at trying to make the actor resemble a younger version of Bruce Willis, who plays the same character in the film 30 years older. Right from the start this comes across as a preposterous and needlessly distracting decision. With the last Batman film and Inception under his belt, I declare Gordon-Levitt to be the ‘It Boy’ movie star of our day. Part of the reason that we love movie stars is the distinctive and arresting symmetry of their faces and directors should re-sculpt them at their own peril. It is a bad idea from many angles: it inhibits the actor’s facial movements, it makes the mind wander towards other latex-driven performances (Eric Stoltz in Mask! Mickey Rourke in Sin City!) and in general distracts us from the pretty clever set up of this almost-clever-enough little sci-fi story.

BY DAN BUSKIRK FILM CRITIC Looper, the new sci-fi film by writer/director Rian Johnson (Brick, The Brothers Bloom) starts out with a fatal unforced error. It’s the make-up applied to the eyes, nose, and jaw of its star Joseph Gordon-Levitt, a ham-fisted stab at trying to make the actor resemble a younger version of Bruce Willis, who plays the same character in the film 30 years older. Right from the start this comes across as a preposterous and needlessly distracting decision. With the last Batman film and Inception under his belt, I declare Gordon-Levitt to be the ‘It Boy’ movie star of our day. Part of the reason that we love movie stars is the distinctive and arresting symmetry of their faces and directors should re-sculpt them at their own peril. It is a bad idea from many angles: it inhibits the actor’s facial movements, it makes the mind wander towards other latex-driven performances (Eric Stoltz in Mask! Mickey Rourke in Sin City!) and in general distracts us from the pretty clever set up of this almost-clever-enough little sci-fi story.

Gordon-Levitt plays Joe, a man who works as the titular looper. In the rundown dystopia of 2042, a looper is an armed killer whose job entails shooting and disposing of men who magically  appear hooded and cuffed in front of them, time-traveling from the future for execution. High on drugs taken through eye-drops, bored and lonely, the isolated Joe carries out his duties with a world-weariness he conveys via a noirish vice-over. A looper can enjoy a comfortable retirement when he kills the future version of himself that is sent back to be executed, something they call “closing the loop.” There’s trouble to be had if you refuse to kill your future self, something called “letting your loop run” which is just the kind of trouble that Joe finds himself in when he can’t bring himself to blow-away the Bruce Willis that he has grown into.

appear hooded and cuffed in front of them, time-traveling from the future for execution. High on drugs taken through eye-drops, bored and lonely, the isolated Joe carries out his duties with a world-weariness he conveys via a noirish vice-over. A looper can enjoy a comfortable retirement when he kills the future version of himself that is sent back to be executed, something they call “closing the loop.” There’s trouble to be had if you refuse to kill your future self, something called “letting your loop run” which is just the kind of trouble that Joe finds himself in when he can’t bring himself to blow-away the Bruce Willis that he has grown into.

Among the liveliest moments of Looper are with scene-stealer Jeff Daniels as the aging hippie crime boss, Abe. Unshaven and wearing a robe, Abe mixes fatherly concern with a pragmatic ease in killing. Through his eyes, the future is demanding it, what can he do? With Old Joe now on the run we hope to see more of the world of 2042, but it seems like dance clubs and roadside diners differ little 30 years into the future. Joe finally meets himself at a diner and what should be one of the film’s highlight moments is sadly underwhelming. Besides the revelation that Old Joe eats the same steak and eggs as Young Joe (still not watching that cholesterol?) this mind-bending meeting of the self just leads to Old Joe lecturing Young Joe like a scolding, unloving parent. This may be someone’s sci-fi fantasy but it’s hard to imagine who. The film sees itself as thought-provoking but Back to the Future offered about as much insight.

(I should stop here for a second and admit that when when the cinematic presence of Bruce Willis pops up these days, I’d be more inclined to blast away than Young Joe. Willis has long ago given up on showing much versatility and it has been forever since he appeared to be having fun on screen. His dour presence provides no sparks here either. Gordon-Levitt had to wear a faceful of Silly Putty to make way for this performance? Why not just cast Peter Weller, or some actor who believably resembles Gordon-Levitt and be done with it? When Young Joe breaks out into Willis’ self-satisfied Hudson Hawk smirk, it points to a lazy showboating acting style I hope Gordon-Levitt never adopts. Anyway, back to the show.)

Before we can learn much about the world of 2042, the film makes a jarring transition to the countryside. Here, Young Joe is sent to a farmhouse searching for the child who will grow up to terrorize the future as “The Rainmmaker,” eventually killing Old Joe’s first real love. Young Joe is cautiously taken in by a single mother Sara (Emily Blunt) whose little boy grows progressively creepier as the story unfurls.

There are a handful of self-conscious cinematic allusions in Looper, but the one critics have left unmentioned is Nicholas Ray’s 1952 film noir On Dangerous Ground, where a violent city cop played by Robert Ryan learns humanity from a blind farm woman played by Ida Lupino. Somehow Ryan and Lupino could make such a far-fetched connection click, but Looper‘s script doesn’t work hard enough at delivering the final pay-off in which Young Joe’s humanity is awakened. Writer/director Johnson wants us to care about Old Joe’s great romance, yet only shows his objet d’amour in a fleeting montage. And if the eyes are the window of the soul, Young Joe’s are obscured bylatex eyelids. Looper’s story may wrap itself up in a nice arc, but for all its clever plotting, the story’s underfed emotion keeps it from lingering in our memories.