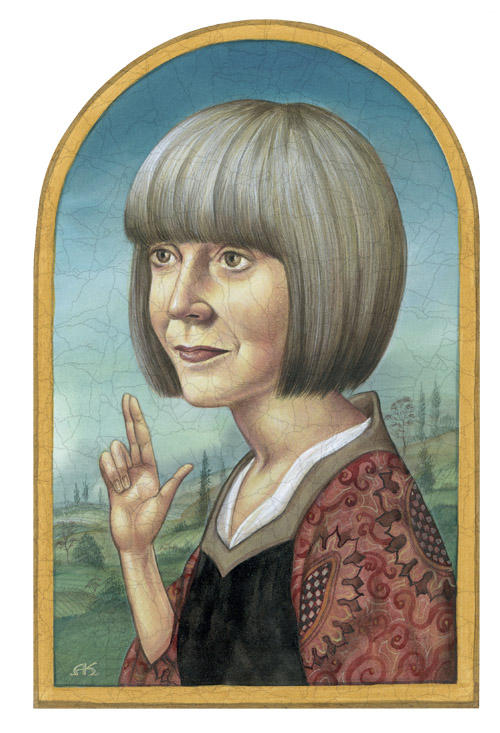

[Artwork by ANITA KUNZ]

BY JONATHAN VALANIA In advance of Anne Rice‘s reading at the Free Library tomorrow night to promote the publication of Wolf Gift, her 33rd novel, we got the doyenne of high goth on the horn for an in-depth Q&A. Discussed: Why her mother named her Howard; How to kill a werewolf. Why she regrets ever using the word ‘vampire’; the interior lives of zombies. Why she returned to the Catholic Church after years of ardent atheism. Why she then turned her back on the Catholic Church and Christianity itself, but still believes in God. The future of the book and the death of publishing as we used to know it. Why she sold off her 10,000 book personal library, most of her jewelry and wardrobe and her vast museum-scale doll collection. What is a typical day in the life of the woman who has sold more than 100 million books.

BY JONATHAN VALANIA In advance of Anne Rice‘s reading at the Free Library tomorrow night to promote the publication of Wolf Gift, her 33rd novel, we got the doyenne of high goth on the horn for an in-depth Q&A. Discussed: Why her mother named her Howard; How to kill a werewolf. Why she regrets ever using the word ‘vampire’; the interior lives of zombies. Why she returned to the Catholic Church after years of ardent atheism. Why she then turned her back on the Catholic Church and Christianity itself, but still believes in God. The future of the book and the death of publishing as we used to know it. Why she sold off her 10,000 book personal library, most of her jewelry and wardrobe and her vast museum-scale doll collection. What is a typical day in the life of the woman who has sold more than 100 million books.

PHAWKER: Thank you very much for taking the time to speak with us. It’s an honor to have you on the blog. Let’s just jump in without further ado. Some of these questions I’m sure you’ve been asked a million times and hopefully you’ll be patient and bear with me. You’re born Howard Allen Frances O’Brien? Please explain.

ANNE RICE: (laughing) Yes, that’s correct. That’s exactly what my name was. My parents thought it would be a great idea to name me after my father, Howard. They thought it would be a very distinctive name for a girl. The priest at the baptism said there was no Saint Howard, and he insisted and they added a saint’s name, so they threw in Frances and that’s how I became Howard Allen Frances O’Brien. Of course I hated it. I absolutely hated being called Howard Allen. Allen was my mother’s maiden name, and I was always called that double name – Howard Allen. I just hated it, so when I walked into the 6th grade classroom and the sister asked me what my name was, I said it was Anne. I changed it, and my mother – being the raving liberal who had named me Howard – said, “Well, if she wants to be Anne, call her Anne!”

PHAWKER: Your mother was just sort of tone-deaf to how much you would’ve disliked being called this?

ANNE RICE: She thought it was a great idea. She told me later that she had once known a young woman named Sydney and she thought it was just  wonderful to have a boy’s name.

wonderful to have a boy’s name.

PHAWKER: Well, Sydney is a little closer to a woman’s name.

ANNE RICE: (laughs) Well it’s a prettier name.

PHAWKER: Moving forward; so you wind up marrying your high-school sweetheart, which I think is adorable. Hopefully this isn’t too personal of a question, but I thought it was great that you guys were high-school sweethearts and that you became life-long partners. I’m just wondering, do you remember the first time that it kind of clicked for you and you were like, ‘this is the guy for me’?

ANNE RICE: That’s a good question, and I remember vividly the first time I laid eyes on him. I remember being impressed with him the first day I ever talked to him. It was journalism class and he was sitting up in the front of the room, and he came back and sat down at the table next to me and said, “I don’t want to be up there by myself.” I remember that after that we had many conversations, and I’m not sure when I fell so tragically in love with him. It wasn’t too long after that, and I never fell out of love with him. That’s just the way it was from there on. Gosh, I could’ve been sixteen those first few weeks of that journalism class, so I would say I fell in love with him by the end of that year or just when I turned seventeen in that October.

PHAWKER: Moving forward, you moved to Haight-Ashbury pretty much at the height of the psychedelic 60’s, but from what I can gather in my readings you never partook. True or false?

ANNE RICE: No, we were there before. It happened a while, we were there. No, I never participated. I really didn’t want to take drugs and was afraid of them, and didn’t like it. I didn’t like smoking marijuana at all. I didn’t like being slowed down by marijuana. I couldn’t imagine why somebody would want to take a drug that caused you to forget the beginning of your sentence before you got to the end. I really was sort of my own self during that period, but it really was sort of interesting to be right in the middle of it, to be living steps from Haight Street when all of that broke loose.

PHAWKER: So even though you weren’t personally taking LSD or smoking marijuana, the culture that it spawned, though – you were not put off by that? Did you find that interesting or did you feel a kinship with it?

ANNE RICE: I really am very reluctant to go along with mass movements. I’m not a conformist, I don’t like conforming, I don’t like being told what we’re all doing today, or what we’re for, or what we’re against. I really didn’t much like the conformist attitude of many of my hippie friends. I really didn’t want to be a card-carrying hippie. I didn’t really want to sign on to do all of the things they were doing, and so forth. I really just wanted to go to college and write books when I grew up – I wanted to get an education. They were really counter culture people, and they were counter education and counter achievement, really. It was a drop-out movement. It was a movement of people that rebelled, and in many ways it was a wonderful movement. It changed America in many beautiful and wonderful ways, but for someone like me who was desperate to finish college and desperate to achieve something in life, it wasn’t particularly exciting or interesting.

PHAWKER: Fair enough. Moving forward; in 1973 you write Interview with the Vampire in the wake of the death of your daughter Michelle a year prior to leukemia. Some speculated that the creation of the child vampire, Claudia – played by Kirsten Dunst in the movie version – was your way of channeling your grief. Can you speak to that at all?

PHAWKER: Fair enough. Moving forward; in 1973 you write Interview with the Vampire in the wake of the death of your daughter Michelle a year prior to leukemia. Some speculated that the creation of the child vampire, Claudia – played by Kirsten Dunst in the movie version – was your way of channeling your grief. Can you speak to that at all?

ANNE RICE: Well, I think looking back on it it certainly was how I channeled my grief but at the time I didn’t know it. I was just writing away…after Michelle’s death I took out all of my short stories and bits and pieces of novels and tried to pull something together. I wanted to go on with my life and I came across this short story, Interview with the Vampire, that I had done before and I began developing it into a novel. But I really didn’t think at all about consciously what I was doing. You know, if I had I would have been blocked. I mean, how could I have ever plunged into something so unusual as Interview with the Vampire to talk about my daughter’s death. I mean, I would have been just stopped in my tracks if someone had said, “Look what you’re doing.” But, there I was writing this fantastic novel – literally, a fantasy – and suddenly there was a child vampire in it who would never grow up. The character was certainly not my daughter; the character was just herself in the novel. Later, when I looked back of course it was all about me. It was all about a family, and a child, and that child’s death and how it completely shattered the hero of the novel, who was really me.

PHAWKER: Prior to this, how did you latch onto vampires? Why did you find vampires so alluring?

ANNE RICE: It wasn’t any big decision, I was just thinking one night how interesting it would be to interview a vampire. Supposing you could actually get a vampire to actually tell you what it was like to be a vampire, to be immortal. I simply started the story and the vampire was speaking, and I loved it. It felt very good to me. I think I discovered what I was good at and what I could make work accidently. I mean, I don’t remember there being any direct inspiration at that time. You know, it wasn’t like I saw any movie or read a book, or anything like that. I just thought it would be really cool to do that.

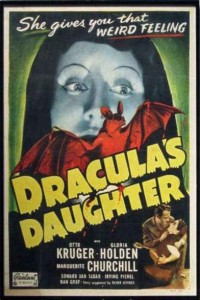

PHAWKER: Had you seen horror movies or seen vampire movies prior to that?

ANNE RICE: When I was a child I had. I had seen Dracula’s Daughter, which was a wonderful black and white movie from the 30’s. I saw that in the neighborhood show when I was a kid and thought it was great, and really, I guess from looking back on that that’s what shaped my idea of the vampire as this elegant, doomed aristocrat struggling with a terrible urge to take human life. But I can’t remember anything back in those years that prompted me to write the story. I don’t remember seeing any vampire film or anything. I mean, they were on a night on the Late Late show but I don’t remember even really watching them at that time. I don’t remember, I just remember wanting to do the story and I did the story over maybe two or three times until I decided to let it go into a novel.

PHAWKER: The books became very popular — scratch that, extremely popular. You almost single-handedly made vampires sexy, and re-invented vampires  in the popular imagination. I’m curious what you think of some of the antecedents of that such as True Blood and Twilight, neither of which would have happened without ANNE RICE, in my opinion. Do you watch True Blood, and if so what do you make of it, and for that matter, Twilight, as well.

in the popular imagination. I’m curious what you think of some of the antecedents of that such as True Blood and Twilight, neither of which would have happened without ANNE RICE, in my opinion. Do you watch True Blood, and if so what do you make of it, and for that matter, Twilight, as well.

ANNE RICE: I actually like the show. I watched the first two or three seasons and really enjoyed it. I think it’s in the fourth season now, isn’t it? I haven’t caught up with it lately, but I do love that show and I think Charlaine Harris is just wonderfully clever. I read the first Sookie Stackhouse novel and part of the second, which is a lot more than I read of most people in fiction. I just think she’s a wonderful writer, but I guess I enjoy it. I enjoy what they’re doing, all these different writers – the way they’re taking that rich concept and developing it in completely new ways. I think it’s very interesting. They’re not doing what I did. I mean, basically for me, the vampires were heroes and heroines. They were larger than life and I both wanted to be intimate with them, but I also wanted them to be glamorous and mythic.Whereas where I tried to keep the glamour and the mythic quality of vampires – even when writing about them in an intimate way – I think that what Charlene Harris has done and what Stephenie Meyer has done is to domesticate them somewhat. To say the guy next door is a vampire, the guy at the corner bar is a vampire, the guy in high school next to you in biology class is a vampire, and that’s just another very interesting way to go with it. So, I enjoy seeing what they’re doing, even though it’s not what I did at all.

PHAWKER: Do you see vampires as tragic figures? Are they superhuman or are they somehow subhuman? Is their eternal life more of a curse or a blessing?

ANNE RICE: I think they’re tragic figures and they’re superhuman. They definitely have a great gift. They have immortality, and I would find that myself if that were offered to me I would find that almost irresistible. But they’re also tragic figures because as they live longer and witness more of the beauty of life, they become more keenly aware that they’re cut off from life. They cannot procreate except by making other vampires, and they come to love the things that they prey on. At least that’s how I’ve always seen them, and that’s a big theme in The Vampire Chronicles. Many of the characters talk about that.

PHAWKER: Ah, that’s great. Back to the future, I was talking about how vampires sort of zeitgeisted in the nineties, and I think it’s safe to say that since the turn of the century zombies have taken that center-stage place in pop culture. Does the zombie phenomenon interest you at all? Does the notion of zombies intrigue you?

ANNE RICE: It hasn’t so far. I mean, I must confess, though I was knocked out by the original Night of the Living Dead. I thought it was a great black and white movie – my god, it was wonderful. I mean, it was grim and horrible but it was just a great film. But no, I’ve never figured a way to get into the character of the zombie. I mean, everything with me needs a character and a soul. I loved the Lon Chaney wolf man because he’s tormented. When I discovered the original Frankenstein, the actual book by Mary Shelley, I was amazed to discover that the monster tells the story for a long period of time in the novel. That’s what interests me, and I just can’t take that to a zombie. You can’t invent the zombie as maybe in a walking coma that he can’t get out of when he’s actually thinking of Keats and Mozart in his head. (laughs) But, I mean, I can’t think of any way to do it!

PHAWKER: That’s a very good point. Zombies are kind of personality-less, aren’t they?

ANNE RICE: Well, if they’re really zombies, yeah, apparently so.

PHAWKER: So, you have in a sense moved on to exploring sort of the werewolf phenomenon as well, correct? Wolf Gift, the new book?

ANNE RICE: Oh yeah, The Wolf Gift, will be published next week and I’m totally into my character, Reuben Golding, the wolf gift.

ANNE RICE: Oh yeah, The Wolf Gift, will be published next week and I’m totally into my character, Reuben Golding, the wolf gift.

PHAWKER: Let’s talk about that. What prompted the move? Just looking to explore new territory? What engaged you about the werewolf archetype?

ANNE RICE: Well, I’ll tell you, it was a casual mention. A friend of mine, the producer of the TV series White Collar that’s on USA on Tuesday nights, Jeff sent me an email in which he mentioned that he happened to see a special on werewolves and that if I ever happened to tackle the werewolf theme he would certainly buy the book. And that’s just sort of an encouraging, friendly comment. I got to thinking about it, and I decided to go ahead with it. I suddenly saw a way to do it: that I would make my werewolf completely conscious while he was a werewolf so that he could experience everything in a sensuous way, and have continuity between the wolf state and the human state. Really, it was just an accident. If Jeff hadn’t mentioned that, I don’t know that I would have gone there.

PHAWKER: Typically, people that are werewolves have no recollection of what they did or what happened to them while in the wolf state, correct? They just wake up, their clothes all ripped and blood around their mouths?

ANNE RICE: Right, exactly, and that’s why I never found them that interesting. So I thought, okay, well let’s change that. Make it different, and make your hero experience it and cherish it, and be aware of it and comment on it. And also, I gave my guy the ability to talk when he’s in that state. So, he’s totally himself but he’s changed by all of the hormones coursing through his body that have caused the transformation. So he has the strength and the capacity to act of an animal, but he’s still Reuben. He’s still a person.

PHAWKER: Do you plot out the origins of werewolf-ism, or do you not even bother with trying to explain that?

ANNE RICE: No, I do provide that story. I don’t want to spoil the book for people, but it does come. That’s a big question with Reuben. He got bit, he doesn’t know by who or why and he has to find that out, and I do give an origin story.

PHAWKER: Whatever you don’t want to disclose, feel free to just say as much, but would it be some kind of a viral thing?

ANNE RICE: Well, no, no. It’s passed by the bite, but it’s still a mystery. I mean, I think to write a really good supernatural novel, for me, to keep it interesting to myself there has to be an aura of mystery to it. He can’t be too clinical, ever. But it’s really fun when that mystery is described in physical detail how it works. So, it’s not like a virus. I mean, it’s a real quick transformative thing that happens, but it is communicated by the bite. That’s how you get the ability to do it, from a werewolf. For Reuben it’s sort of a gift because it becomes his life, you know, puzzling over this and what he can do with this power, and what he shouldn’t do with it. He finds someone who loves him, both when he’s in the wolf form and when he’s in the human form. So, that for me was very important. I like to work out some things about what’s happening, so I explore in there, you know, is it hormones? Is that what the body’s flooded with that actually would make the hair come out? The teeth, and the snout elongating and everything. And so I put enough of that in there to make it make sense to me.

PHAWKER: And the only thing that can kill a werewolf is a silver bullet? Is that correct?

ANNE RICE: No, no, no. In my mythology you’d have to cut the head off of the werewolf. I think that’s going to be true of just about any supernatural creature. You cut their head off and destroy the head, you pretty much destroy the thing itself.

PHAWKER: That makes sense. What about the question of mortality? Is the werewolf immortal or no?

ANNE RICE: Well, let’s say that’s part of the mystery. But it would certainly seem so.

PHAWKER: So after years of atheism, in recent years you returned to the church – and I know that you’ve since left and we’ll get to that – but I wanted to just sort of get back to how the switch flipped from atheism to believing? To my understanding you had a couple of near-death experiences there, some complications…

ANNE RICE: Well, not really, not really. I’ve never had a genuine near-death experience where I’ve gone out of body or seen the light. Nothing like that. Really, I went back to the church about two weeks before I nearly died with diabetes, so it wasn’t anything like that. I simply realized I did believe in God and I really just wanted to rejoin the community of believers. I think I made perhaps a very bad mistake in returning to the Catholic Church, but I can’t regret it, because it’s something that I wanted very much to do.

PHAWKER: What made you say I have to separate myself from this? Even though I still believe in God, or still believe in Jesus Christ, but I’m no longer  going to use the Catholic Church as an avenue to that.

going to use the Catholic Church as an avenue to that.

ANNE RICE: I studied the whole thing for twelve years – I lived as a believer for twelve years. I mean, praying, going to mass, reading the Bible, studying theology, writing two books with Jesus, writing a memoir, all of that. I gradually came to realize – and I could no longer deny it – that I did not believe this personal belief system. I just simply did not believe it. The entire theological endeavor of the Christian belief system, I thought it was founded on contradictions, absurdity, and falsehoods and I simply did not believe it. When I went to the root of all the complex, beautiful theology I found that it was rooted in interpretations of Biblical passages that to me did not make sense at all, I realized I did not believe it. I lost faith. I simply didn’t have faith in that way of looking at the world. In fact, I came to the conclusion that it was not a good way to look at the world. But, I mean, I’m not saying that for anyone else. I don’t want to offend people. I think it works fine for millions of people because they don’t…how should I put it? Maybe it’s that it functions differently for different people, but I’m a person who’s very theologically oriented. I have to really know that what I’m saying I believe. I have to understand it, and I simply couldn’t go on with it any longer. And also, there was also a lot of social and political pressure because the church was doing a lot of things I violently disagreed with. It was persecuting homosexuals, it was campaigning against gay marriage, it was stridently against women having contraceptive rights, or knowledge, or medicine. I was embarrassed by all of those things. I didn’t like being part of something that, I think, had become an engine of persecution and bias. It was very uncomfortable, but you know, I could have kept quiet about theology if those social pressures hadn’t forced me to take a stand. But it was really a theological break. I don’t believe atonement theory, I don’t believe in the elaborate theories of Christianity. The more I studied and the more I came to see what it was all about, the less I could sign on for it.

PHAWKER: Now you’re talking about Christianity in general, and not just Catholicism?

ANNE RICE: Oh yes, Christianity in general. Because, see, I had a great experience with Protestants and Catholics. The two Christ the Lord novels were very well received by both Protestants and Catholics, so I had a lot of email contact with Protestant brothers and sisters. I went on their radio shows, I went on their television shows, I was interviewed, I spoke to them, I read the Biblical scholarship of both Protestant and Christian scholars. I’m very familiar with their differences and with their different ways of looking at the world, and I really have far less sympathy with the Protestant way of approaching things than I do with the Catholics simply because I understand a little more why Catholics do what they do. You know, it’s like my mother tongue is Catholic – I grew up Catholic. But really, my disagreements were with both of them. I simply – It’s rather technical to go into it, but I don’t believe that this is a fallen or broken world. I don’t believe there’s a big rift between us and the creator. I don’t believe we need a savior to save ourselves. I don’t believe that we’re all going to Hell if we do not believe in that savior. None of that really makes any theological sense to me, and when I discovered after years of study the Biblical passages that supposedly support all of that, well, they didn’t. So, and I could talk to you for another five hours about that, passage after passage. To me, it was not a system that I found credible. I didn’t even really find it honorable or honest. I think most Christians are honorable and honest, I understand, because most people haven’t explored it. But, is the system honorable or honest? I would say no.

PHAWKER: Are you implying that it’s really just kind of a racket?

ANNE RICE: No, it’s not a racket. It’s definitely made up of true believers, but they’re true believers that have convinced themselves that they must accept absurdities and contradictions. They have arbitrarily decided that they must. They do not really even believe in using their own intelligence or reason, because they’ve convinced themselves that what’s required of them is that they believe this thing. It’s very difficult to describe, I mean again, I think most of the Christians that I met were certainly honest and honorable, but it was the system that wasn’t honest or honorable. It was the theology itself. There were rationalizations, and a lot of it was sophistry. I simply couldn’t buy it.

PHAWKER: So tell me, then, how would you characterize your current spiritual philosophy or status in the world’ Are you still a believer in God, just not of Jesus Christ as a savior et cetera, et cetera?

ANNE RICE: I believe in God very much. I don’t know whether the Jesus I loved with my whole heart ever existed. I’m not sure at this point, but certainly the Jesus that I wrote about in those two books and loved was very real to me at that time and he is the Jesus of the Sermon on the Mount. But unfortunately, that’s only a part of what the Jesus of Christianity is about. There’s a lot of other baggage that goes along with believing in Jesus. I believe in him, yes, and I love him, but I’m very aware that I don’t embrace all of the other theories attached to him by Christians. So, that’s the way I would answer. What concerns me more than anything in this world is to live a good life: to be honest, and decent, and loving to other people, and to use this lifetime to learn, to love, and to serve. What I hope and pray for every day is that God will guide me in that, and that matters infinitely more to me than any theory of taking a savior to save me from Hell.

PHAWKER: Is your issue with Christianity…is it the theology that came after what’s actually written in the New Testament? Or is it the New Testament itself that you have issues with?

PHAWKER: Is your issue with Christianity…is it the theology that came after what’s actually written in the New Testament? Or is it the New Testament itself that you have issues with?

ANNE RICE: Well, yeah, I would say the whole theology. Like I said, we could talk for six hours about it. I mean, first of all, the way Christianity presents itself. It presents itself as Jesus coming, entering history, bringing the Age of Prophesy to a close by fulfilling prophesy and stopping history, and saying he will return within one generation. Well, that didn’t happen. That clearly didn’t happen. There’s no escaping that when you really study the Bible, if you really study it. If you just listen to quotes being read to you from the pulpit, or you jump around with your pen and underline this and that, fine. But if you really read the gospel, and if you really read Paul, it’s very clear that this was a Jewish apocalyptic cult and Jesus did not come back within one generation, and he didn’t come back in Paul’s lifetime as Paul expected. And then what you see, I think, is that you see the religion beginning to develop a complex theology of atonement, in which they insist Jesus’ death was necessary for the sins of the world. And they’ll tell you that if you read the Old Testament you’ll see all of this being foreshadowed. Well, I didn’t see it foreshadowed in the Old Testament and I didn’t see anything wrong with the Jewish religion that implied anybody needed anybody to bring it to an end. What I saw was a vigorous, beautiful, Jewish spirituality throughout the OT – the Old Testament – and I saw nothing necessarily implying that we were all going to Hell if we didn’t have Jesus as our savior. But this is basically what all Christians were telling me, whether they were super sophisticated Anglicans or Catholics, or very simple Protestants. I mean, they were all telling me essentially the same thing – that that’s basically what Jesus is. I mean, I would ask people, I would sit down at dinner and say, “What did Jesus save you from, exactly?” And they would say, “Well, from Hell!” I said, “Well what do you mean? Do you really think all of us were going to Hell before Jesus came? Do you think Isaiah went to Hell? Do you think Moses did? Do you think Adam and Eve did? Where in Genesis does it say – where does God say anything about Hell?” He says nothing! Anyway, do you get what I’m saying? We can talk about it forever.

PHAWKER: I mean, I don’t mean to unwind that whole ball of string, but I am happy to talk about it if you want to. But let me ask you this, then – are there any other organized religious philosophies that you’ve adopted or felt a kinship with? Judaism, Hinduism, Eastern religions?

ANNE RICE: No, no, I would prefer to stay away from all organized religion. I would prefer to pray directly to God and, as I’ve said, my focus is to live a good life. That what I write should have a moral compass, it should have some meaning, it should maybe give somebody something of value when they read it. That I should treat every person that I meet with love and kindness – whether it’s a person on the street, or in a shopping mall, or anybody I meet in any capacity. In an email, in a Facebook post, at a book signing, anywhere I go, treat that person – if at all possible – with love. Don’t do anything to diminish that person’s dignity, or life, or right to the pursuit of happiness and spiritual development. That’s basically what matters to me. I pray a lot during the day, and I don’t really want to gather with a group of people to do it simply because I don’t like all of the baggage that comes along with the group. I mean, when I was Catholic my church was paying out hundreds of thousands of dollars – millions, multi-millions — to settle claims by people and young children that had been abused sexually by priests. I’ll never forget sitting there in the pew realizing the amount of money I had contributed to the church and hearing that Cardinal Mahoney in Los Angeles had paid out 660 million dollars to dismiss sexual abuse claims. And I said to myself, “My god.” I never want to be involved in an organization like that again because there’s no need for that. I mean, God is with us and we can talk to God ourselves. That’s what the universe says to me.

PHAWKER: Don’t you think that the Catholic Church, I mean, there’s any number of instances we can point to, but specifically this most recent priest pedophile thing that you were talking about – haven’t they completely vacated any kind of moral authority that they might have once held? How? I think  they really need to just turn out the lights and close the door, they’re out of business!

they really need to just turn out the lights and close the door, they’re out of business!

ANNE RICE: Oh, absolutely! Absolutely. I would agree with you. I think it’s rather maddening to see them carrying on as if they still have credibility – they don’t. But on the other hand, I know priests right now and I know fellow Catholics that haven’t been touched by this. They go to mass, they live a sacramental life, they don’t know anybody who’s been abused, they don’t have a priest in their parish that has been accused and they’re largely untouched. So I can’t say to those people, well look at this suspicious, really…so much that you should quit. But on the other hand there are a lot of people that are quitting and are walking right out of the pews. In Europe, in the Unites States, in Australia, and in England and Ireland. Just saying, the heck with you guys! Look what you’ve done! So yeah, they’re facing their biggest catastrophe since the Reformation, and one of the worst things about it is that they continue to deny it and cover it up. The arch-conservatives in the Catholic press are appallingly defensive, trying to blame everyone else but themselves and their own clergy for what’s happened. It’s a revolting mess, there’s no question. But again, for me it was the whole system. It was Protestants and Catholics. It’s not just that one church or that one denomination, it’s all of it. It’s the whole belief system. I’m as sickened by the Westboro Baptist Church as by anything that the Catholics have done. By these Republican candidates standing up and claiming that God has told them to run for the presidency, and then seeing how thoroughly they can attack women’s rights, how they can outdo each other in attacking the rights of American women. It’s all rather discouraging to me.

PHAWKER: When it comes to the religious right, I just don’t see the teachings of Christ in anything that they’re talking about. I don’t see anything about mercy, or love, or forgiveness, or helping the poor, or humbleness, you know? It’s all about hating gays and controlling women’s sexuality, and starting wars.

ANNE RICE: It’s all “pelvic politics.” That’s what Kathleen Kennedy Townsend calls it. Pelvic Politics, they’ve become obsessed with it. It’s very unfortunate; I was reading a book today about human nature by an author called Wilson, and he points out in this book that when religion is no longer serving a purpose for people, they’re pretty much dooming themselves. And I think that this obsession with pelvic politics on the part of Protestants and Catholics together, I think it is their doom that they’re spelling with this because people today have to plan their families. Nobody in America can have thirteen kids like my great-grandmother. It’s not possible. When the churches refuse to help people face the dilemmas of their time, when they turned away, when the Catholic Church wouldn’t even OK the pill people just had to ignore them. I know my great-grandmother had thirteen children, my grandmother had nine, my father had five, and I have two. This is the reality, as you know, when you’re sitting there facing what it means to have a child. I mean, in bringing that child up and to prepare that child for life. And then I think about my father and his eight brothers and sisters were scrambling around in two rooms. Today, they would be taken away by the state – I hate to say it, I’m not for the state taking people away, but probably they would be. Because they would be considered undernourished, under medicated, under-cared-for, undereducated, everything. And, I don’t know, for these churches not to recognize that this is what these people were facing. I’ll tell you what did it more than anything else in the twentieth century that sealed their downfall. It wasn’t the women’s movement; it was the rise of the child as a person. The twentieth century really saw the beginning of pediatrics, child labor laws, juvenile courts, identity of the teenager, and an interest in the child as a person. And that was new – that had never happened in history. For about three hundred years we’ve had children romanticized and people writing about children and feeling sorry for them and trying to make things better, but it really culminated in the twentieth century in actual laws that protected children from exploitation. And the Churches just really didn’t see that coming. They put everything they had behind the patriarchal family. They opposed child labor laws because they thought it interfered with the family’s right to have little Joey pick blackberries on the farm. You know?

PHAWKER: They still say that.

ANNE RICE: They thought all of these things. That’s when they began, I think, to really wane in influence and became unfortunately the victims of their fringe elements.

PHAWKER: Very good point. They’re actually, literally talking about that now in trying to roll back child labor laws on the grounds that it’s telling family farmers how to raise their children.

ANNE RICE: Oh, I know. Newt Gingrich, right? He’s against it, isn’t he? It’s ridiculous. They don’t understand what they’re talking about. They don’t know history, these people. I don’t care what Gingrich says he knows – he doesn’t. He doesn’t know anything about poor people, or children, or adolescents, or what goes on.

PHAWKER: Moving on, in 2010 you auctioned off most of your possessions. — jewelry, wardrobe, books, a vast, museum-sized doll collection is my understanding. Why?

ANNE RICE: Well, I just couldn’t keep it any longer. I had collected all of that stuff in New Orleans when I actually had two homes and a large building in which to put all of those things. I owned three different buildings in New Orleans, and I owned apartments in Miami and New York, and I really just didn’t have the room. I mean, I’m older and I live out here on the coast now in a small house, and I just didn’t really have anywhere to put that stuff. I mean, there was a time when that doll collection was on display and thousands of people could see it every month. But I don’t have any place now to put those dolls, and so I thought it was better to give them over to an auction company and let them go back into the world, and they have.

PHAWKER: Very Zen.

ANNE RICE: I sold tons of books, too. I mean, I had books from all of those buildings, and libraries, and condominiums, and all those books I sold to Powell’s Books in…Seattle? Or maybe in Portland, Oregon. I don’t know where they are, but it was Powell’s.

PHAWKER: Roughly how many books are you talking about that you sold off?

ANNE RICE: Oh, ten thousand? I don’t know how many but it was quite a lot.

ANNE RICE: Oh, ten thousand? I don’t know how many but it was quite a lot.

PHAWKER: Wow. Did you read all of those books?

ANNE RICE: I had been through a lot of them, and in fact I was very glad that Powell’s was willing to buy books that had underlining, and annotations, and notes in them because I thought that if you donated books like that they’d get thrown in the trash. But Powell’s bought them and was happy selling them as ANNE RICE’s library, so I felt like these books would have some life, you know?

PHAWKER: Well, also, it’s not just anybody’s underlining and notations, it’s ANNE RICE’s.

ANNE RICE: Well. Yeah. Whatever. (laughs) The main thing was that I hated to see that stuff go into the trash in a library sale, all marked up and unusable. So when Powell’s agreed to buy all of that I was thrilled and we shipped out tons of books. I still have books I have to get rid of here. I don’t have enough room anymore to keep my whole library in the house, and I’ve discovered, you know, the old lesson – if you can’t find a book, you don’t own it!

PHAWKER: Good point. What’s a typical day in the life of ANNE RICE these days?

ANNE RICE: Well, I get up early, drink coffee, and read Los Angeles Times and The New York Times, and then I usually check my emails and go on Facebook. I’ll often post a link to a story in The New York Times, or an editorial, or a column or something that I’d like to discuss with the people on the page. I may post maybe three or four of those in the morning, or just look and see what the people on the page have brought to the page. They bring lots of news stories and different items, and we’ll talk about that. And then I’ll usually start writing or doing research right in the morning around eleven o’clock and I’ll work until about seven at night, and knock off usually around seven-thirty or eight and then just kick back and read, you know?

PHAWKER: And then, if you’re not researching those would be your writing hours as well?

ANNE RICE: Mhmmm. The best time would be from about eleven in the morning until about seven at night.

PHAWKER: And when you’re hot, do you write for eight hours straight, or…?

ANNE RICE: No, you know when I was writing The Wolf Gift I did, when I was really rolling I might do that. But if I complete a chapter and I’m really happy with it, I’ll knock off whether it’s two o’clock, or five o’clock, or whatever. I don’t want to begin another one until the next day. I don’t know, I go with it as far as I can.

PHAWKER: Do you write all the way through and then go back and re-work it and fix things, or do you labor over every sentence and paragraph before you move forward?

ANNE RICE: I labor over it as I move forward. I move back and forth, and back and forth as I proceed, and when I finish it’s finished. I may go back within the next twenty-four hours, but basically it’s done. I developed that method of working years ago before I had a computer and really, to me, it’s a good way of getting things done.

PHAWKER: As opposed to just writing a long draft that you’re going to go through again and having to re-write most of it?

ANNE RICE: Yeah, I can’t deal with that. I can’t work in drafts, so I work in one draft. And really, that’s all there is. I mean, The Witching Hour, The Wolf Gift – that’s one draft. You know, there’s corrections and changes right up to pub time. Maybe I’ll add some dialogue when I’m copy editing, when I’m going through the galley and correcting I might add some sentences, or see something Reuben says doesn’t make sense. It’s refinement. It’s editing and refinement.

PHAWKER: The other book that you published last month – The Songs of Seraphim, Of Love and Evil – is the second in the series about angels. I’m curious,  are angels just a metaphor for you or do you think that angels are real?

are angels just a metaphor for you or do you think that angels are real?

ANNE RICE: Well, you know, I could tell you when I started that book I thought angels were real and now I’m not so sure they’re real. I’m really eager to do the third book and get into a different kind of adventure for the hero and a lot of different temptations that he will face about whether the angels are real. I get into that a little bit in Of Love and Evil. He’s confronted by a spirit that tells him that they’re not real, and that he’s being duped by spirits. The person puts forth another vision of the spirit world, and I’d like to explore that further. And also, I love that character – Toby. I love his being a converted hitman who really wants to do good and I think he needs to be sent on even more difficult missions than ever before to do good. His present life, I want to get into that more, too.

PHAWKER: What’re your thoughts on the state of publishing? Print versus ebooks, the future of publishing – what are your thoughts on all of that?

ANNE RICE: Well, obviously it’s all up in the air. We’re being told every day that bookstores are closing, that New York publishing is in crisis and at the same time Amazon gets bigger and bigger and really provides an enormous array of wonderful services to writers and readers, so it’s all in flux. I don’t frankly know what’s going to happen. I know that people love real books as much as they ever have, but what the inroads will be of Kindle and Nook and digital publishing, I’m not sure. I know on my Facebook page we talk about it a lot, and when I first started talking about it people were overwhelmingly anti-ebook. They were totally pro real book. Now when I post on it, more, and more, and more people have said that they have definitely learned to love their Kindle. That they’re traveling with it, that they use it for textbooks – whatever. So, clearly, that whole dimension is growing. I think what we’re going to see is maybe an end to the chain bookstores and maybe the return of the small, individual store.

PHAWKER: Interesting point.

ANNE RICE: I mean, even now people are saying that little, small, independents are opening again in the wake of the closing of Borders. So, perhaps as more of the big chains go under there will be more little stores that provide people with wonderful services like readings for children, poetry readings in the evening, book signing where the author comes and has coffee with people. I mean, people love that, and they need that, and they want that, and so maybe that will come back. You know, and maybe the big bucks stuff will be online. Let Amazon be an end to it online. I think that it can be worked out. I think that publishing in trying to fight Amazon accomplishes nothing. The only thing to do is to cooperate, and learn, and think of something new because fighting them and saying things like, ‘If Amazon publishes books, we won’t carry them.’ That’s nonsense. That’s not going to help anybody. That’s like throwing pebbles at a giant.

PHAWKER: It’s the lesson that should’ve been learned from the music business who fought Napster instead of embracing it and wrecked their business model.

ANNE RICE: Exactly. I mean, there’re many creative things that aren’t being done. Like, for one thing, publishing is not coming up with a different kind of real book. I mean, if you look at a book today it looks very much like it did one hundred years ago. It might be possible to make a real book out of synthetic material that is impervious to dampness, doesn’t rot, doesn’t weigh as much, and make that a very beautiful artifact – but you don’t see any initiative going into that.

PHAWKER: Well, don’t you think that what will survive the Internet is objets d’art. Something that’s collectible and rare, that’s a beautiful artifact.

ANNE RICE: Yes, exactly. Beautiful artifacts, but do you see a creative explosion in that? No! Look, The Wolf Gift is a handsome book – I mean, Knopf does a beautiful job on it, but it’s a book like a book from forty years ago. It’s paper from trees, you know, the type of cover that they put on books and have been putting on them for forty years. But, think if they made something really new that was so beautiful – I mean, people who love books, they love different editions, covers, leather-bound editions, and illustrated editions, and I wish publishing was doing a lot more of that creative stuff to compete with these books. Now, I think it would be a wonderful thing. I don’t see aggressive marketing. You know, I don’t see like when you download a book on Kindle, I don’t see special links to help you order a hardcover copy if you love that book. You know, at a discount maybe. There’s a lot that can be done. I think that they will all improve. This is a period of just nightmarish confusion. Everyone is just getting better at the whole thing, but right now I feel frustrated. I wish I was an entrepreneur and could just invest in making a new synthetic book that was durable and beautiful, with a beautiful cover. I mean, think of the beautiful things that are made of synthetics today – just think of clothing.

ANNE RICE: I mean, and shoes, and handbags, and I don’t know – radios and computers. The beauty of the Apple computer and the way they made it look gorgeous. You don’t see that happening in the book world here. But maybe somebody will come in, maybe there will be a Steve Jobs or a Gates will come into the book world and do that, and change everything. It’s not happening so far.

PHAWKER: Just to close out that topic, you mentioned that you read The New York Times and the Los Angeles Times – do you read that online or do you read the hard copy versions of those papers?

ANNE RICE: Oh no, I read the paper. I like to go outside, pick it up off of the sidewalk, come in, peel off the plastic cover, stretch it out, pour my coffee, open it up, and read it. But then, when I go to Facebook I link to the website.

PHAWKER: When somebody comes up to you and says ‘I want to be a writer and I want to do what you’ve done’ what do you say to them?

Ann Rice: Go for it. Just go for it. Do what you want to do. Write the books you dream of writing. Write the books you want to read, protect your vision, and don’t pay any attention to criticism. If somebody doesn’t get it, just keep on walking.

PHAWKER: Do you read your own reviews?

ANNE RICE: Sometimes, yes, quite a bit. I don’t necessarily read them more than once, but I mean I certainly check out every review at least one time.

PHAWKER: You don’t take it personally? It’s not wounding for you, it’s not emotional for you?

ANNE RICE: It can be, but the only thing to do is just keep going. I mean, you just read them and you think, ‘Okay’ and you just keep going. I think all authors are deeply hurt by bad reviews, they always have been. Consider the history of people who were just devastated, like Melville, by the reviews they got. Emily Bronte, they opened her desk after she was dead and all they found in there were five bad reviews of Wuthering Heights. I mean, that’s sad. Carson McCullers was so devastated by Edmund Wilson’s review of The Member of the Wedding she said she’d never read a review again. I mean, it’s always painful but the only thing to do is to look them over and say ‘Okay’ and just keep going. If you learn something – good! If you don’t learn anything, keep moving. But fairness, or getting angry about it, you’ve got to let that pass. It’s not easy, but you have to do it. There’s no fairness. It’s just a jungle out there.

PHAWKER: Well do you think that criticism has a constructive role to play other than the hawking of books? As far as advancing the form, advancing a writer’s trajectory, or…

ANNE RICE: Almost never. It’s too random. I mean, if you were talking about the opera, or ballet, or painting, possibly. The critics in those areas usually know a lot about what they’re critiquing – and even rock music. There are very knowledgeable critics of rock music who write very sophisticated criticism in Rolling Stone and in The New York Times. But when it comes to books and movies – as you probably know – it’s totally random. I mean, people write about movies that they have no understanding of and they’re not part of the audience for it, and they do the same thing with books. You know, they’ll even say, you know, ‘I never liked this author and I don’t really get what this is about’ but they’ll write five paragraphs about why you shouldn’t buy this book. I mean, if you did that with a restaurant – if you tried to write a restaurant review in The New York Times where you said, ‘I hate Chinese food, I don’t know anything about it, and I don’t know why anybody likes it’ and then tried to write a review, well there’d be a riot. The restaurant would try to sue the paper. But you can do that with a book review any day of the week. You know, you can just write a review savaging detective novels and just pan a book because you don’t like detective novels. Or you can just say it’s another self-centered, stupid feminist novel and why do women bother. You know? And that kind of drivel is published all over in the book world. Because nobody expects the critic to have any special knowledge of what he’s writing about. I remember a Star Trek review, it started with the line, “Another big, stupid, boring Star Trek movie.” Well, you know, if I feel that way about a book I don’t review it. If I look at it and I think I don’t get this, and I don’t know who the audience is for this, and I don’t know what’s being attempted, and I don’t know what’s being  accomplished then I don’t review the book. I pass on it. But unfortunately most people who review books don’t do that.

accomplished then I don’t review the book. I pass on it. But unfortunately most people who review books don’t do that.

PHAWKER: Well, like The New York Times employs a lot of novelists who review other novelists’ books. What do you think about that practice?

ANNE RICE: It’s usually a waste of time, but I do think The New York Times does fabulous reviews of non-fiction. They do get knowledgeable people to write about history, and politics, and art and I read those all the time. I almost never read the fiction reviews in The New York Times. Occasionally, but not too often.

PHAWKER: Last question. If you could go back in time to the beginning of your career early 70’s and do anything differently, what would it be?

ANNE RICE: Probably not use the word vampire.

PHAWKER: [laughs]

ANNE RICE: Maybe use the word ‘immortal’ or ‘blood drinker’? Just to try to avoid the incredible, dismissive prejudice I encountered with my early novels. Now that’s no longer the case now, I don’t really fight that anymore but at the time in 1976 when Interview With the Vampire came out it caused quite a bit of scorn. Maybe I wouldn’t use the word – but on the other hand a person could look back on that and say it was a genius thing that you used the word, because it attracted everyone’s attention. I don’t know.

PHAWKER: I certainly think you made the world reassess the word.

ANNE RICE: (laughing) Eventually. Eventually. But yeah, I don’t know. That’s really the only thing that comes to mind. I think I’ve had a wonderful life. I mean, I can’t complain. I feel very grateful for all of the different things I’ve experienced, so I really don’t think much in terms of regret.

PHAWKER: Is it true that you’ve sold 100 million books?

ANNE RICE: You know, they keep saying that, but I don’t know. I can tell you this – I’m published all over the world, like almost every day something trickles in from some country. I’ve got thirty books out there and they’re translated so widely, I mean, they’re everywhere. So very probably, yes. There’re so many translations. Like when a translation of Interview with the Vampire goes out of print in a country, well a few years later you re-translate it and it goes back into print with another publisher. So, possibly so. I’m not sure that all writers catch on with the foreign market like that, and I’m not sure why it happened with me, but it’s a wonderful thing. It’s very nice. It’s a great comfort to know your work is being read in Hebrew, or Japanese, or Portuguese in Brazil, in the Canary Islands in Spanish. I find it wonderful and I love it. For a long time I collected the foreign copies until I no longer had the space to keep them.

PHAWKER: All right, well I think we’ll leave it there. Thank you very much for giving me so much time and for engaging my questions so thoroughly, and I wish you well.

ANNE RICE: Well thank you very much, I actually enjoyed it very much and I hope you send me a link to your blog.

***

TANGENTIALLY RELATED: Abraham Lincoln Vampire Killer

RELATED: Daniel Day-Lewis, eat your heart out? The first trailer for “Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter” has arrived (yes, this movie is actually happening), filled with grand speeches, old shots of Washington D.C. and our 16th President chopping down vampires with an axe. Directed by Timur Bekmambetov (“Wanted”), the film follows Lincoln (Benjamin Walker) as he looks to navigate the country through a Civil War, where vampires in the South look to defeat the North, thus enslaving all of human existence. (Just as it’s told in history text books!) MORE