[Illustration by ALEX FINE]

Bill Giles, The P.T. Barnum Of The Phillies, And The Creature He Brought To Life

BY ED KING Pouring Six Beers at a Time and Other Stories from a Lifetime in Baseball is the new autobiography from Philadelphia Phillies’ longtime executive and partner, Bill Giles. The book, like the man I spoke to, has the jovial tone of a true dreamer. A Bill Giles tale is punctuated with knowing chuckles and the uncanny sense that the story is taking on new details since its last telling.

BY ED KING Pouring Six Beers at a Time and Other Stories from a Lifetime in Baseball is the new autobiography from Philadelphia Phillies’ longtime executive and partner, Bill Giles. The book, like the man I spoke to, has the jovial tone of a true dreamer. A Bill Giles tale is punctuated with knowing chuckles and the uncanny sense that the story is taking on new details since its last telling.

Giles came to the public eye in the Philadelphia sports scene as the Master of Fun and Games, fearlessly orchestrating wacky and often ill-advised promotions that pied-pipered capacity crowds to the then-state-of-the-art Veterans Stadium. In the aftermath of the Phillies’ lone World Championship, and the sudden sale of the team to a group of buyers assembled by Giles, for a brief and shining moment he became the caretaker of the Phillies’ most glorious era. But before long, after one too many lineups scribbled on cocktail napkins branded him as the Bumbling Leader of the infamous front office Gang of Six piss-poor decision makers. Eventually Giles would be relieved of his team presidency and returned to his one great talent: selling the sizzle in America’s favorite past time, even when the steak wasn’t so hot.

sudden sale of the team to a group of buyers assembled by Giles, for a brief and shining moment he became the caretaker of the Phillies’ most glorious era. But before long, after one too many lineups scribbled on cocktail napkins branded him as the Bumbling Leader of the infamous front office Gang of Six piss-poor decision makers. Eventually Giles would be relieved of his team presidency and returned to his one great talent: selling the sizzle in America’s favorite past time, even when the steak wasn’t so hot.

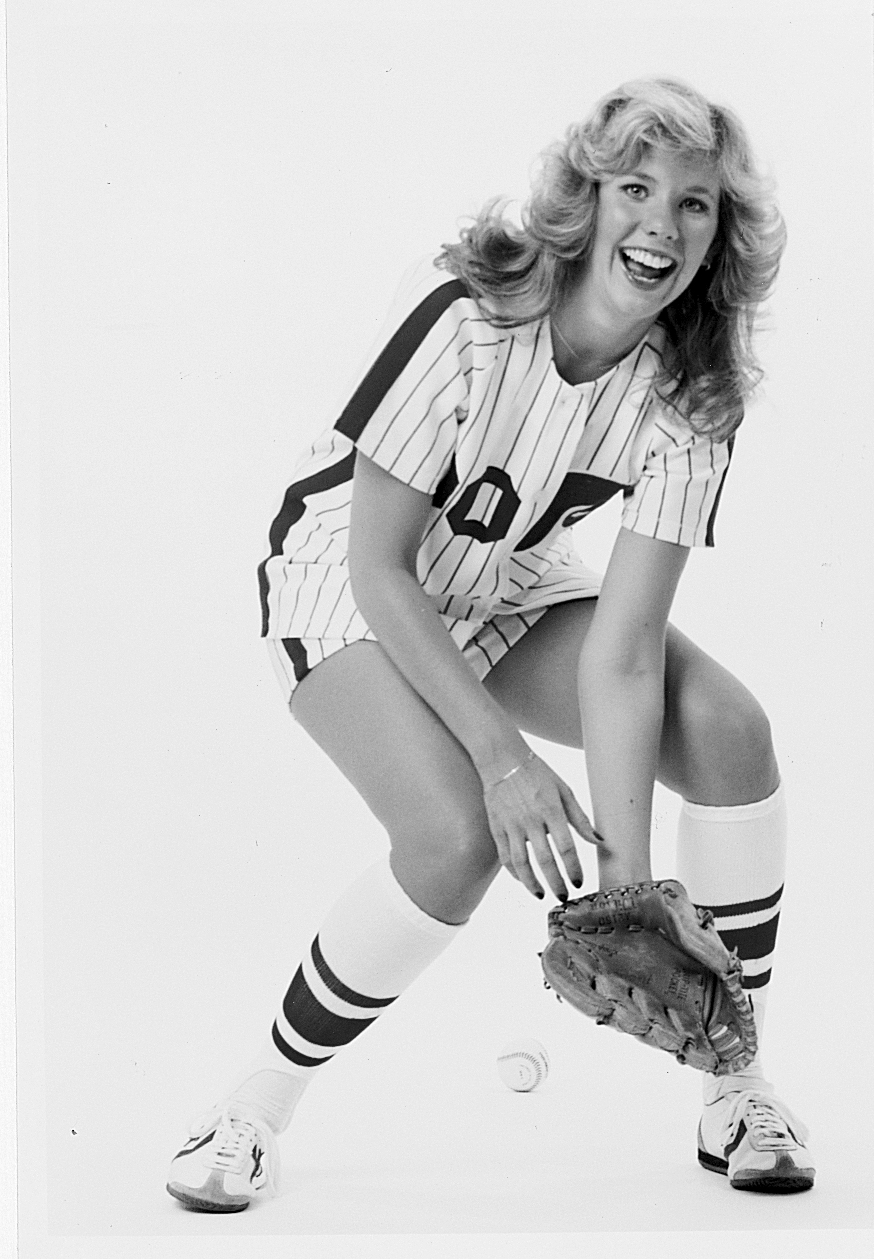

He would have an integral role in creating the Phils’ new ballpark, and making it feel like a home-way-from-home for the the great unwashed, the long-suffering 700 Level faithful. As an only child and the son of then-Cincinnati Reds president and later National League President Warren Giles (Bill’s mother died when he was seven years old), baseball was Bill’s family. His godfather was the great Branch Rickey. And though often perceived as a complacent old boy’s network, the Phillies, perhaps more than any othe team in baseball, feels more like a family than ball club. Perhaps more than anything else he’s cooked up — the Fanatic, the ball girls, the parachutists and the tight rope walkers — this sense of inclusion and belonging and shared sacrifice will be his legacy.

PHAWKER: How might your childhood experiences have influenced your role in fostering the family atmosphere of the Phillies?

BILL GILES: It’s true, baseball fosters family relationships. You know, a study was done that determined that 67 percent of our fans come with another member of their family, which is amazing. It’s also amazing the amount of family names that have stayed in the game: the O’Malleys, Walter and Peter; Larry and Lee McPhail; the Giles family, the Rickey family. It’s also true that a lot of former players come back to be broadcasters, coaches. Once you get baseball in your blood you never want to leave it. An amazing thing about the Phillies is that there must have been about 18 marriages where the people met each other at Veterans Stadium: our PA announcer met and married an usherette; John Vukovich, our coach, met and married an usherette. There were many of those [chuckles] ‘happenings’.

[Giles was present for the birth of the Houston Astros and, as a result, the birth of what would be known as modern baseball in the 1970s: multi-purpose stadiums, artificial playing surfaces, and the world’s first domed stadium or, as he coined it, the ‘Eighth Wonder of the World.’ Before baseball’s space age could take root, however, the franchise originally dubbed the Colt 45s played two seasons in a glorified high school park. Even when the Astrodome opened, however, the grass was not immediately greener on the inside of the Lucite dome.]

PHAWKER: Did the Astros players need some coaxing to play on an artificial surface?

BG: I think the players generally liked it because the two years prior to the Astrodome they were playing outdoors, and the mosquitoes and the heat were so bad they were very happy to get indoors and get away from the animals. But the only problem, of course, with the Astrodome was in the twilight and the daytime it was very hard to follow a baseball for the outfielders. Therefore we had to paint the Lucite plastic roof in order to make it so that ball could be seen by the outfielders, but then of course when you did that the grass died.

***

“You know, looking back on it, it was amazing how I switched completely when I left the Reds and went to Houston. I followed the Reds, of course, but I didn’t have any emotional ties to them, and the same thing happened in 1969, when I moved from the Astros to the Phillies. Immediately my blood turned Phillies red.”

***

PHAWKER: I wasn’t aware that the Astrodome originally had grass.

BG: Yep, it did. And it was interesting because the plastic roof had two pieces of plastic, but in between they had prisms that diffused the light so that the field would not look like a waffle iron. That was kind of an amazing invention, and everything was fine until the grass died. We didn’t know what to do about the grass — we talked about playing on dirt. Then my boss, Judge Roy Hofheinz said, “Well, you can make carpet, why can’t you make plastic carpet and make it look like a baseball field?” I’ll never forget the meeting with Monsanto, the people that made carpets, they said, “Yeah, we can make that.” And Judge Hofheinz said “How much is that going to cost?” They said a million dollars. Hofheinz said, “That’s exactly what I was going to charge you to name it Astroturf!” So we got it free.

***

[In 1969, after the Astrodome took its fully futuristic form, Giles would leave the Astros to join the Phillies as Director of Business Operation. He would help usher out the final year of Connie Mack Stadium and prepare for the launch of the Phillies’ foray into modern-day baseball. As I read Giles’ book, I was transported back to when I was a boy, going to games at the Vet. I recalled a number of opening days, sitting in the picnic area, Philadelphia Phil and Phyllis, the center-field fountain, the multi-colored seats.]

***

PHAWKER: You were key to establishing the ambiance of the Vet in the ’70s. As you say in your book, it was a fun exciting place, and it wasn’t just because of the play on the field. It took a few years for the team to become competitive. Was there a turning point when the Vet became less fun for fans?

become competitive. Was there a turning point when the Vet became less fun for fans?

BG: Well, you know, early on we didn’t have a very good team in the early ’70s, and the attendance at Phillies games was quite bad in the late ’60s. So I created a lot of crazy promotions with the philosophy that if we could get ‘em in there once to see whatever the crazy promotion or concert was, that they would like the experience and then come back when there was just a little old ballgame.

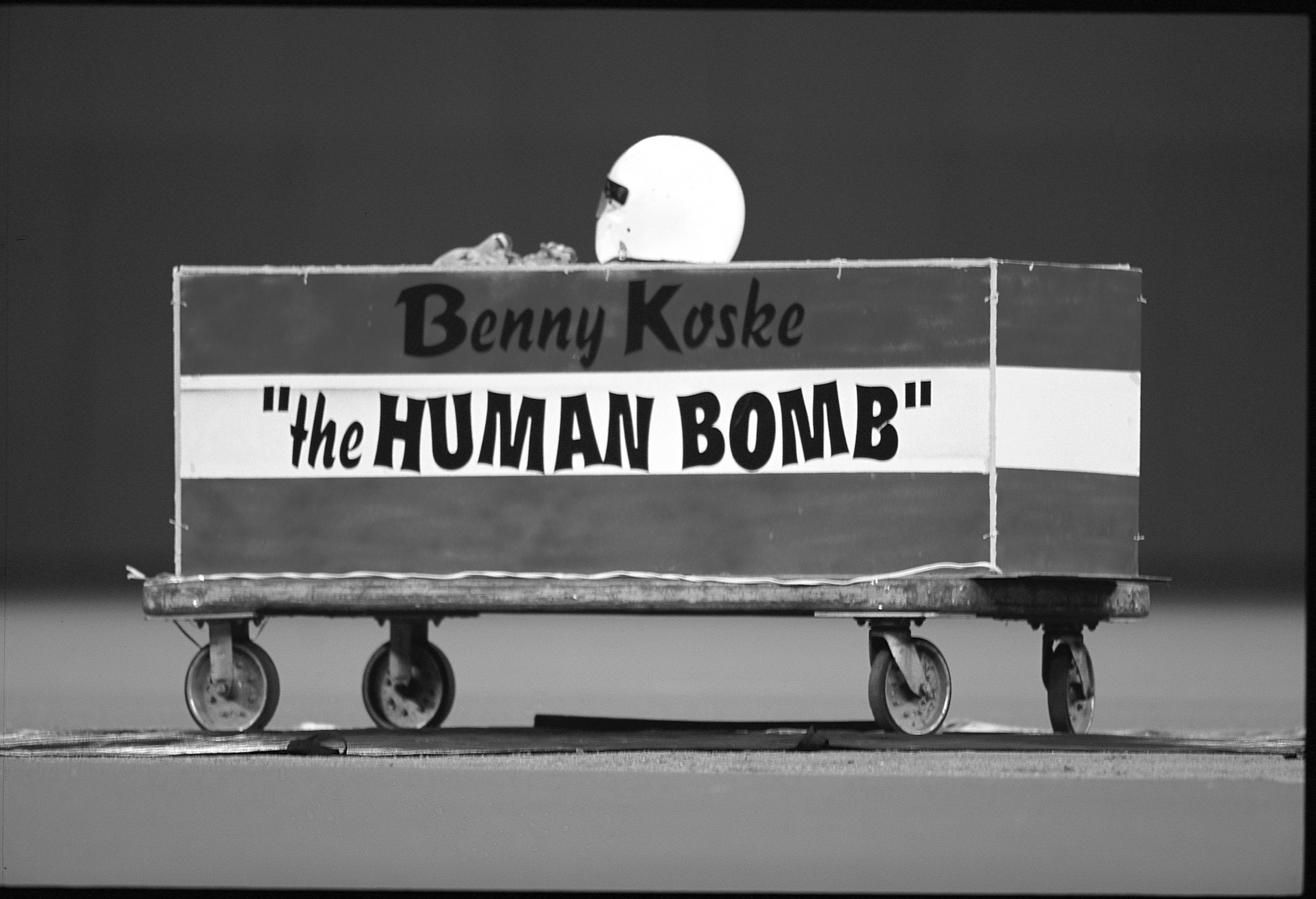

We had a lot of fun with it, then the team got good. Then of course, when you have a better team, as we did in ‘76, ‘77, etc., then the ball club becomes more of the focus than the Dionne Warwick concert or the cash scrambles or Bennie the Bomb.

PHAWKER: I saw Bennie the Bomb. Did you have a favorite out of all the stunts you pulled?

BG: I think the most successful was the Great Wallenda walking across the wire. We actually did that twice. And Opening Day was always special to me, because growing up in Cincinnati they would let kids out of school so they could attend the day game. I always wanted to call attention to the fact that the baseball season was beginning, so that’s why I had helicopters and Kiteman and Cannon Man.

PHAWKER: In all of your promotions over the years, did you have one that you really thought would be a killer but it just didn’t work for the fans?

BG: The Highest Jumping Easter Bunny was one of my great failures, and the ostrich race and the duck race — those were probably the ones that I laugh at as I look back on them as complete failures.

PHAWKER: Growing up as a Reds fan and then following your time in Houston, did it take some time for you to feel like a Phillies fan, a Philly guy?

BG: You know, looking back on it, it was amazing how I switched completely when I left the Reds and went to Houston. I followed the Reds, of course, but I didn’t have any emotional ties to them, and the same thing happened in 1969, when I moved from the Astros to the Phillies. Immediately my blood turned Phillies red.

happened in 1969, when I moved from the Astros to the Phillies. Immediately my blood turned Phillies red.

PHAWKER: Knowing the Phillies fans and our penchant for booing the hometown team, are there ever times when you want to boo along with the fans?

BG: Oh yeah. Even when I sit at home and watch them on TV I kind of mentally boo when somebody doesn’t do something right. Even last night I was booing a couple of times in my head, not out loud, of course. Yeah, Phillies fans are very, very knowledgeable and they’re very passionate. You really can’t fool them. They are so wise, it’s amazing to me. I’ll never forget in 1970, we had two or three catchers get hurt and Doc Edwards, who was about 42 years old and hadn’t played in three years — he was one of our coaches — and we put him into a game. He had to catch a game. He threw a runner out in the second inning, and he got a standing ovation. You’ve probably never seen that before and will never see it again, but it told me these fans understood that this kind of old guy was not supposed to be throwing runners out. From that point on I knew they knew what was going on on the baseball field. If you don’t hustle and you’re a Philly player, they’ll really let you have it. The only sad thing is the fans boo a lot of the good players. Mike Schmidt was probably booed more than any Hall of Fame player I’ve ever known. It was kind of sad that they would do that, but if he would pop up or strike out with the bases loaded, he would get booed.

PHAWKER: Yep, I was guilty. With your background in PR and your understanding of the game and this fan base, were there players who were best suited and players who were least suited to this city?

BG: There’s definitely more of an appreciation by the fans to blue-collar players. Pete Rose was very popular with the fans because of the way he played the game. He was not particularly a pretty boy. A lot of the really good-looking guys, like Von Hayes and Darren Daulton — the women liked them, but Joe Sixpack didn’t particularly like those kind of guys. Pete Incaviglia and Jim Eisenreich, those kind of blue-collar players who’d get their uniform dirty and hustle all the time, they’d become the most popular in Philadelphia. And right now we have Chase Utley, and he’s loved by everybody because he plays so hard all the time.

PHAWKER: If the 1980 Phillies played the 1993 Phillies, who would win in a seven-game series?

BG: Well, if you did it on a computer and took numbers and things, I think the ‘80 team would win, but the desire and character of the ‘93 team probably would win. It was amazing, the players on the 1980 team didn’t like each other; the 1993 team, everybody was close-knit and they remain close friends today. It was completely different mix of people.

desire and character of the ‘93 team probably would win. It was amazing, the players on the 1980 team didn’t like each other; the 1993 team, everybody was close-knit and they remain close friends today. It was completely different mix of people.

PHAWKER: So I take it that following a big victory, the ‘93 team is the one you’d want to join for a postgame celebration?

BG: Yes, definitely. I was closer personally with a lot of the guys on the ‘93 team. Occasionally, I would go into the locker room after the game, where the Macho Row group of 12 or 15 would be eating fried chicken and drinking beer in the trainer’s room, and I would go and help celebrate a victory with them once in a while.

PHAWKER: There’s a legendary story about you and a cocktail napkin: You were out with some writers and excitedly jotted down the projected lineup for what would turn out to be a disappointing stretch in the mid-’80s.

BG: Right, in the early ’80s I often would write on cocktail napkins, having a vodka martini, making out lineups and figure out who would be playing centerfield, second base, and those kind of things. And then I always had my yellow legal pad, and I was always playing around with trades, lineups, coaches, managers. I had a whole bunch of yellow legal pads, and I was always playing around with ideas.

PHAWKER: I did that too, but I was in my Mom’s basement. It must have been a real thrill to be living out your childhood dream of running a ball club. Was handling the criticism that would come with the job difficult?

BG: I handled criticism very well, in fact a lot of my lieutenants wondered why I didn’t get more upset. I knew that was part of the deal, and I knew that when your team doesn’t win they’re going to blame me or the manager or the general manager. It never bothered me too much. Some talk shows bother me, but the writers were generally pretty fair and criticized me when I should have been criticized.

***

[In 1997, Giles was relieved of his role as president of the Phillies. As chairman of the club, he would concentrate his efforts on the development of a replacement park for the crumbling Veterans Stadium.]

***

PHAWKER: You’re key to the development of Citizens Bank Park. Most Phillies fans agree that it’s a breath of fresh air. Are you satisfied with how it’s turned out?

BG: You know some people ask me what my legacy is. There are lots of things I’m very proud of: the Phillie Phanatic, signing Pete Rose, getting to the World Series three times in 12 years, but the thing I’m most proud of is the development and design and getting the money to build Citizens Bank Park, because I don’t think there’s ever been a sporting facility built that people enjoy as much as people enjoy Citizens Park. People have a ball there, and not necessarily do the Phillies have to be a pennant-winning team. It’s just a good outing whether we’re in last place or first place.

PHAWKER: Do you regret not building in Center City, as you had initially desired?

BG: No. I did prefer downtown but I’m not so sure it would have worked as well as it’s working now, although I think it would have been better for the city economically. Now when I go downtown about 6 in the evening, it’s pretty crowded around the area I wanted to put it, so I’m not so sure the traffic would have worked as well as the drawings looked at the time.

PHAWKER: With Barry Bonds approaching Hank Aaron’s record and the scrutiny around performance-enhancing drugs, do you regret that the game overlooked these issues for so long?

BG: I think there are two problems. I think people were ignorant. I had no understanding of steroids — really never even thought about it until the last two or three years, when it’s become such a public thing. And when Mike Schmidt was hitting all those home runs or McGwire or whoever, it never entered my mind that they might have been doing anything other than exercising and pumping iron, maybe. So the whole thing became a shock to me when it all surfaced. It’s very sad that Bonds’ attempt to beat Hank Aaron is so tainted in the minds of everybody. It would be wonderful if we could find out really whether Bonds did do something wrong or not. He’s never been proven guilty, nor had McGwire. You know, in those days it really wasn’t illegal, as far as baseball rules were concerned, to do any of that stuff. Now, of course we have a good system in place where it is illegal. So, this is not a good thing. However, baseball seems to demand from the media and the public a little higher level of ground rules. I mean, it’s hard for me to imagine that many, many football players didn’t do something, because they make their living with muscles. I wish Bonds would either be proven guilty or innocent before he gets to Aaron’s record, because it’s going to be tainted.

never even thought about it until the last two or three years, when it’s become such a public thing. And when Mike Schmidt was hitting all those home runs or McGwire or whoever, it never entered my mind that they might have been doing anything other than exercising and pumping iron, maybe. So the whole thing became a shock to me when it all surfaced. It’s very sad that Bonds’ attempt to beat Hank Aaron is so tainted in the minds of everybody. It would be wonderful if we could find out really whether Bonds did do something wrong or not. He’s never been proven guilty, nor had McGwire. You know, in those days it really wasn’t illegal, as far as baseball rules were concerned, to do any of that stuff. Now, of course we have a good system in place where it is illegal. So, this is not a good thing. However, baseball seems to demand from the media and the public a little higher level of ground rules. I mean, it’s hard for me to imagine that many, many football players didn’t do something, because they make their living with muscles. I wish Bonds would either be proven guilty or innocent before he gets to Aaron’s record, because it’s going to be tainted.