ILLUSTRATION by LUKE MCGARRY

BY RITA BOOKE* Message boards and email lists devoted to David Foster Wallace, who became a literary it-boy with the publication of “Infinite Jest” in 1996, fell silent with his suicide in 2008 after an paralyzing bout of depression. Recent news has brought a bright spot to fans of the postmodern master: the University of Texas at Austin has acquired the entire DFW archive. Handwritten drafts of IJ, childhood poems, his personal book collection, it’s all there for us to (soon) see. For DFW’s devoted, the archive promises a thrilling look inside our hero’s beautiful mind, but it’s also a gut-punching reminder that this is all we’re ever going to get from Our Man. (Yes, we actually call him that.) For now, the Dave faithful will have to keep squinting at the tiny pdfs on UT’s website until the collection opens to the public this fall. Materials from the posthumous The Pale King will be added to the archive after the book’s release in April 2011.

BY RITA BOOKE* Message boards and email lists devoted to David Foster Wallace, who became a literary it-boy with the publication of “Infinite Jest” in 1996, fell silent with his suicide in 2008 after an paralyzing bout of depression. Recent news has brought a bright spot to fans of the postmodern master: the University of Texas at Austin has acquired the entire DFW archive. Handwritten drafts of IJ, childhood poems, his personal book collection, it’s all there for us to (soon) see. For DFW’s devoted, the archive promises a thrilling look inside our hero’s beautiful mind, but it’s also a gut-punching reminder that this is all we’re ever going to get from Our Man. (Yes, we actually call him that.) For now, the Dave faithful will have to keep squinting at the tiny pdfs on UT’s website until the collection opens to the public this fall. Materials from the posthumous The Pale King will be added to the archive after the book’s release in April 2011.

Even for obsessive fanboys and gushy nerdgirls, ahem, who have read every word he put to paper and know ridiculous trivia like what brand of tobacco he  dipped (Skoal) and his curious taste in magazines (Cosmo), there’s still plenty of pulse-quickening new stuff here that’s well worth the eye strain. The sneak peeks into DFW World, not surprisingly, are parts silly and sad, flip and sincere, snarky and empathetic. There’s a large dog-eared dictionary with words circled, one for each letter. Try these on for size: Abulia. Benthos. Cete. Uxorious. Valgus. Witenagemot. (Dave never got to X, Y and Z.) Dorky, funny and so totally ADD (or maybe OCD), his collection of weird words kind of sounds like how he wrote. DFW’s personal library is also part of the archive, including heavily marked up copies of books by his friend and idol Don DeLillo, Cormac McCarthy and — wait for it — Mary Higgins Clark. “Where are the Children”? WTF, Dave? The scholars are stumped on that one, which is pretty awesome.

dipped (Skoal) and his curious taste in magazines (Cosmo), there’s still plenty of pulse-quickening new stuff here that’s well worth the eye strain. The sneak peeks into DFW World, not surprisingly, are parts silly and sad, flip and sincere, snarky and empathetic. There’s a large dog-eared dictionary with words circled, one for each letter. Try these on for size: Abulia. Benthos. Cete. Uxorious. Valgus. Witenagemot. (Dave never got to X, Y and Z.) Dorky, funny and so totally ADD (or maybe OCD), his collection of weird words kind of sounds like how he wrote. DFW’s personal library is also part of the archive, including heavily marked up copies of books by his friend and idol Don DeLillo, Cormac McCarthy and — wait for it — Mary Higgins Clark. “Where are the Children”? WTF, Dave? The scholars are stumped on that one, which is pretty awesome.

Scrutinizing the scribbles inside his paperback copy of Rabbit, Run — phrases like “sad smelling” and an all caps “RABBIT MOURNS HIMSELF” — hint at DFW’s irritation that he’d revisit in a 1997 piece for The New York Observer on John Updike, a “literary phallocrat.” Think a book review can’t be laugh-out-loud hilarious? Read that one. On the other end of the spectrum, it’s cool to see from the scribbles inside DeLillo’s 1976 novel “Ratner’s Star” that it provided direct inspiration for themes and characters that would wind up in Infinite Jest. Beyond the inside-baseball literature dweebery, the most touching piece of the archive that we’ve been shown so far is the sticky notes he used for an IJ revision that look like they came from the Hallmark store’s “office humor” collection. Purple post-its with lame wacky cartoon characters saying “I told you this would happen!!” marking the pages of the 20th century’s greatest novel. Brilliant and banal. Why is that so damned heartbreaking? As amazing as this archive is, looking at it makes his death real in a way it wasn’t before. Now the most we can do is pore through his papers, looking for secret clues in his notations and chicken scratch and doodles, hidden pieces of his a-ha moments and hair-pullingly obsessive meta-ruminations. We’ve got to extract whatever undiscovered gold exists in this mine, because that’s it. No more books, no more nothing. The end.

*(aka JOANN LOVIGLIO)

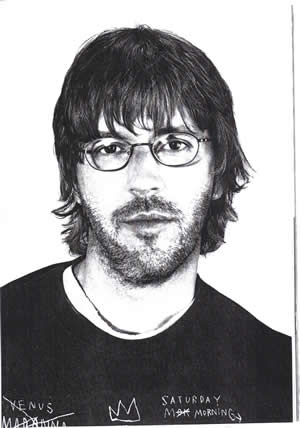

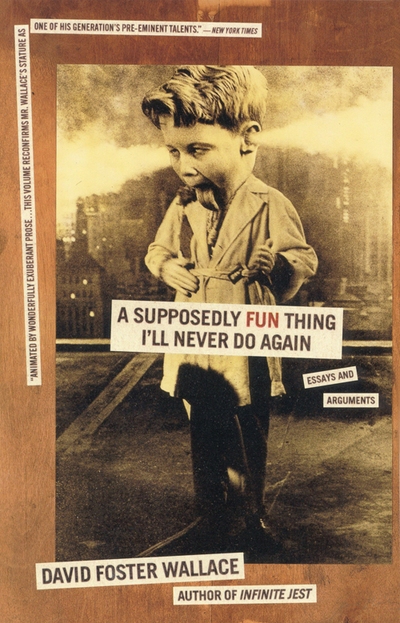

RELATED: By now you may have heard. David Foster Wallace—author of the splendidly outrageous 3-pound mega-novel Infinite Jest, MacArthur Foundation “genius” grant winner, the most influential and innovative fiction stylist of his generation, the smartest, funniest, strangest, most endearing and (let’s just say it) the greatest writer under 50 in America—killed himself at his Claremont home on Sept. 12 [2008]. He hung himself. By mid-morning on Sunday the 13th, thousands of his readers were placing disbelieving phone calls, sending disconsolate e-mails (I got one whose subject line said simply, “fuck”), and posting grieving Web site comments to their disbelieving, disconsolate and grieving friends and fellow readers. A recent New York Times piece compared the shock that Wallace’s suicide created among the literary community to how Kurt Cobain’s suicide affected the rock world, and there’s something to that. For many of us—even for those like me who didn’t even know him (I met him once, for five minutes)—his death felt like a fierce personal blow, close to home, family-intimate, and the weeks since have been like stepping through a Kubler-Ross minefield of denial, anger, bargaining, depression, but not yet—not even close—acceptance. I find myself rereading the essays collected in A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again with the usual sloppy grin on my face—some of them can make you laugh so hard they have literally given my fiancee asthma attacks—only to realize that much of the pleasure his writing has always given me comes from the comforting fact that, until now, there’s always stood a human being somewhere on the other side of that ingenious prose, that someone as sweet, knowing, beguilingly hilarious and drop-dead brilliant as Dave Wallace was somewhere, reliably, on the planet. Now there’s not, and I keep getting blindsided by that knowledge. MORE

RELATED: By now you may have heard. David Foster Wallace—author of the splendidly outrageous 3-pound mega-novel Infinite Jest, MacArthur Foundation “genius” grant winner, the most influential and innovative fiction stylist of his generation, the smartest, funniest, strangest, most endearing and (let’s just say it) the greatest writer under 50 in America—killed himself at his Claremont home on Sept. 12 [2008]. He hung himself. By mid-morning on Sunday the 13th, thousands of his readers were placing disbelieving phone calls, sending disconsolate e-mails (I got one whose subject line said simply, “fuck”), and posting grieving Web site comments to their disbelieving, disconsolate and grieving friends and fellow readers. A recent New York Times piece compared the shock that Wallace’s suicide created among the literary community to how Kurt Cobain’s suicide affected the rock world, and there’s something to that. For many of us—even for those like me who didn’t even know him (I met him once, for five minutes)—his death felt like a fierce personal blow, close to home, family-intimate, and the weeks since have been like stepping through a Kubler-Ross minefield of denial, anger, bargaining, depression, but not yet—not even close—acceptance. I find myself rereading the essays collected in A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again with the usual sloppy grin on my face—some of them can make you laugh so hard they have literally given my fiancee asthma attacks—only to realize that much of the pleasure his writing has always given me comes from the comforting fact that, until now, there’s always stood a human being somewhere on the other side of that ingenious prose, that someone as sweet, knowing, beguilingly hilarious and drop-dead brilliant as Dave Wallace was somewhere, reliably, on the planet. Now there’s not, and I keep getting blindsided by that knowledge. MORE

DAVID FOSTER WALLACE: Because certain myths about both addiction and halfway houses die hard, I’ll  give you a little bio. I was raised in a solid, loving, two-parent family. None of my close relatives have substance problems. I have never been in jail or arrested–I’ve never even had a speeding ticket. In 1989, I already had a BA and one graduate degree and was in Boston to get another. And I was, at age 27, a late-stage alcoholic and drug addict. I had been in detoxes and rehabs; I had been in locked wards in psych facilities; I had had at least one serious suicide attempt, a course of ECT, and so on. The diagnosis of my family, friends, and teachers was that I was bright and talented but had “emotional problems.” I alone knew how deeply these problems were connected to alcohol and drugs, which I’d been using heavily since age fifteen. Every single one of my mental-health crises had followed a period of heavy bingeing on marijuana, tranquilizers, and alcohol. I had first vowed to quit at age nineteen; the longest I’d ever gone without any sort of substance was three months. I was convinced that this was because I was weak, or because I really did have intractable mental problems which only drugs and alcohol gave me any relief from. I therefore spent most of the 1980s on the horns of a dilemma that many addicts and alcoholics understand very well. On the one hand, I knew that drugs and alcohol controlled me, ran my life, and were killing me. On the other, I loved them–I mean really loved them, as in the sort of love where you’ll do anything, tell yourself any sort of lie to keep from having to let the beloved go. For most of the late 80s, my method for “quitting” drugs was to switch for a period from just drugs to just alcohol. Then I’d switch back to drugs in order to “quit” drinking. The idea of months or* *years without any chemicals at all was unimaginable. This was my basic situation. I both wanted help and didn’t. And I made it hard for anyone to help me: I could go to a psychiatrist one day in tears and desperation and then two days later be fencing with her over the fine points of Jungian theory; I could argue with drug counselors over the difference between a crass pragmatic lie and an “aesthetic” lie told for its beauty alone; I could flummox 12-Step sponsors over certain obvious paradoxes inherent in the concept of denial. And so forth. MORE

give you a little bio. I was raised in a solid, loving, two-parent family. None of my close relatives have substance problems. I have never been in jail or arrested–I’ve never even had a speeding ticket. In 1989, I already had a BA and one graduate degree and was in Boston to get another. And I was, at age 27, a late-stage alcoholic and drug addict. I had been in detoxes and rehabs; I had been in locked wards in psych facilities; I had had at least one serious suicide attempt, a course of ECT, and so on. The diagnosis of my family, friends, and teachers was that I was bright and talented but had “emotional problems.” I alone knew how deeply these problems were connected to alcohol and drugs, which I’d been using heavily since age fifteen. Every single one of my mental-health crises had followed a period of heavy bingeing on marijuana, tranquilizers, and alcohol. I had first vowed to quit at age nineteen; the longest I’d ever gone without any sort of substance was three months. I was convinced that this was because I was weak, or because I really did have intractable mental problems which only drugs and alcohol gave me any relief from. I therefore spent most of the 1980s on the horns of a dilemma that many addicts and alcoholics understand very well. On the one hand, I knew that drugs and alcohol controlled me, ran my life, and were killing me. On the other, I loved them–I mean really loved them, as in the sort of love where you’ll do anything, tell yourself any sort of lie to keep from having to let the beloved go. For most of the late 80s, my method for “quitting” drugs was to switch for a period from just drugs to just alcohol. Then I’d switch back to drugs in order to “quit” drinking. The idea of months or* *years without any chemicals at all was unimaginable. This was my basic situation. I both wanted help and didn’t. And I made it hard for anyone to help me: I could go to a psychiatrist one day in tears and desperation and then two days later be fencing with her over the fine points of Jungian theory; I could argue with drug counselors over the difference between a crass pragmatic lie and an “aesthetic” lie told for its beauty alone; I could flummox 12-Step sponsors over certain obvious paradoxes inherent in the concept of denial. And so forth. MORE

RELATED: Celebrating The Life And Work Of David Foster Wallace

PREVIOUSLY: Let’s All Make Love In Jest

PREVIOUSLY: David Foster Wallace Kills Self