BY JONATHAN VALANIA FOR THE INQUIRER To rock boys coming of age in the late ’70s and early ’80s, the brothers Gibb were known primarily as the fey, toothy, Members Only-jacketed target of the Disco Sucks backlash that greeted the blockbuster sales and grating ubiquity of their Saturday Night Fever soundtrack.

But unbeknownst to many, the Bee Gees also had an amazing career in the ’60s, creating deathless psychedelic-pop singles and ambitious album-length statements that explored complex themes and experimented with all manner of instrumentation and orchestral arrangements.

Even back then, it was their harmonizing – as rich and distinct as the Beach Boys or the Beatles at their best – that put them over. In the wake of the mega-success of the Bee Gees’ disco years, the ’60s sides were relegated to the dustbin of oldies radio, and strangely disconnected from their image as dance-floor hitmakers.

relegated to the dustbin of oldies radio, and strangely disconnected from their image as dance-floor hitmakers.

Likewise, the band’s ’60s catalog had been neglected – held in limbo by messy legal disputes and lawsuits – and mostly chopped into one bargain-priced Best-Of after another, which only served to decontextualize the hits from the albums they came from and confuse the narrative arc of their pre-disco career. (The band pulled the plug on the Bee Gees as a performing unit with the 2003 death of Maurice Gibb.)

These days, the Bee Gees’ hipster cachet looms larger than ever, especially with the kind of people who savor Wes Anderson films for their impeccably curated soundtracks. Any number of alt-rock luminaries – from the Flaming Lips to the Shins, the Arcade Fire to Belle & Sebastian – sing the trio’s praises and crib liberally from its ’60s psych-pop palette.

And thanks to a new deal with Warner Bros., the Bee Gees’ back catalog is being remastered, repackaged and reissued.

The reissues series launched late last year with The Studio Albums 1967-1968, an expansive six-disc collection that includes three studio albums – Bee Gees’ 1st, Horizontal and Idea, in both mono and stereo mixes – plus three discs of alternate takes and unreleased tracks from the albums’ recording sessions (including a pair of cloying Coke commercials). It’s an embarrassment of riches for anyone who likes pop dreamy, heart-shaped and full of reverb.

NOW PLAYING ON PHAWKER RADIO

There’s an oft-told tale about how the Gibb brothers found their calling in showbiz. As schoolboys in Manchester, England, in the early 1950s, the brothers were supposed to lip-sync to a record in a talent contest. On the way there, Maurice dropped the record and it shattered. So they actually sang the song instead, and the rousing audience response convinced them they were meant for the stage.

Around this time, the Gibb family relocated to Australia, where the brothers served a long apprenticeship on the teen pop circuit, honing their harmonies and their musical chops, and learning their way around a recording studio. In 1966, they decided to return to England, specifically swinging London, which had become the epicenter of all things pop, mod and psychedelic.

They’d sent ahead some demo tapes. Robert Stigwood, about to become one of the major British rock impresarios of the ’60s and ’70s, liked what he heard. He signed the group to a five-year deal, and spared no expense promoting it. When a single from their Aussie days tanked on the charts, the brothers regrouped, soaked up the sights and sounds of Carnaby Street, and signed on drummer Colin Petersen and guitarist Vince Melouney.

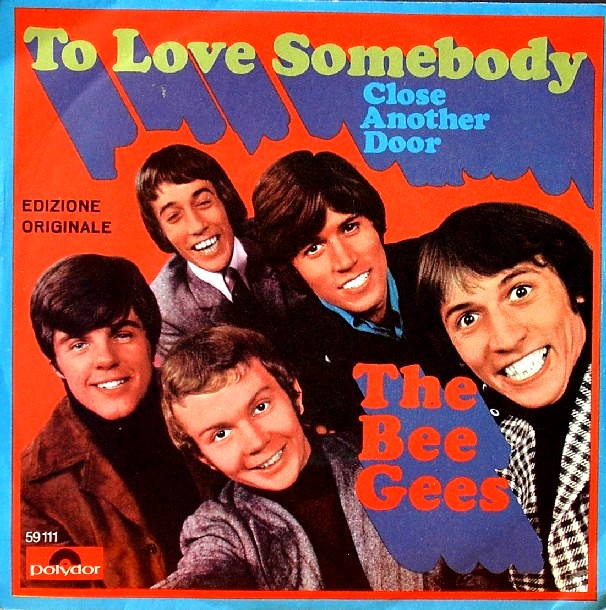

They began writing and recording in an accessible-but-ambitious style that seemed to pick up where the Beatles’ Revolver left off – with baroque, experimental, lushly orchestrated arrangements augmenting harmony-drenched guitar pop. Bee Gees’ 1st, in 1967, yielded what is arguably one of the oddest breakout debut singles in pop – “New York Mining Disaster 1941.” It was followed by the the sublime single and beloved pop song “To Love Somebody,” which was written by the Gibbs for Otis Redding to sing, but the soul legend died before he had a chance.

When the band went back into the studio months later to record Horizontal, it began producing itself, experimenting with a tougher, late-’60s rock sound (witness the trippy organ and pealing guitar riff on the wonderful “World”), though the folk-rock of “Massachusetts,” the album’s major hit, was buoyed by shimmering strings and glimmering glockenspiel.

strings and glimmering glockenspiel.

Idea, in 1968, splits the difference between the swooning psychedelia of the band’s debut and the fuzz-tone rock of contemporaries like Cream and the Yardbirds and the sunbeam harmonies of the its debut, yielding yet another hit with “I’ve Gotta Get a Message to You.”

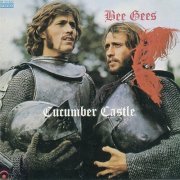

Swelling egos and sibling rivalries would put an end to this fertile and modern-sounding phase of the band’s\ career. An argument over which song to release as a single from 1969’s Odessa – next on Rhino’s reissue list – resulted in Robin’s leaving the band and releasing, ahem, Robin’s Reign, while Maurice and Barry carried on as the Bee Gees for one final album, the unfortunately titled Cucumber Castle, which may well have been the inspiration for Spinal Tap’s “Lick My Love Pump.”

No matter, the first days of disco would soon be upon us.