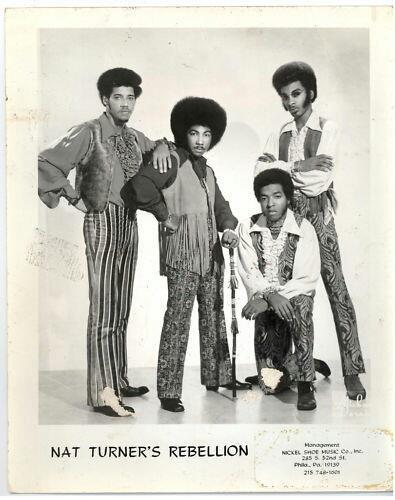

BY SEAN HECK The Nat Turner Rebellion was a circa late ‘60s/early ‘70s Philadelphia funk-soul quartet who took their name from the infamous slave uprising led by the titular Nat Turner in 1831. Which was a very bold move in a time of pronounced racial strife for a band that trafficked in Black Power themes in addition to the de rigueur hippie musings and love song tropes that were typical of their late ‘60s soul contemporaries. The Nat Turner Rebellion’s debut LP was cut at the legendary Sigma Sound Studios and set for release in 1972 on the Philly Groove label, but for reasons unclear the album never saw the light of day and the group soon disbanded and faded into obscurity.

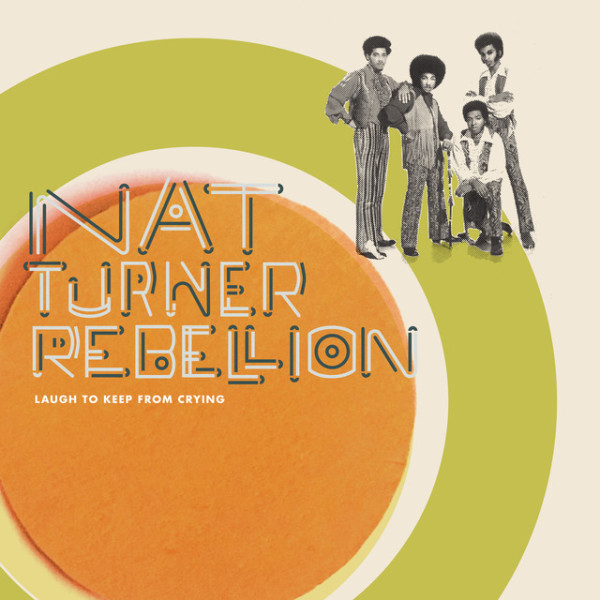

But 47 years later, Nat Turner Rebellion’s music was discovered by Drexel University’s music department  amongst a trove of unclaimed Sigma Studios recordings that had been gifted to the school back in 2005. On March 29th, MAD Dragon Records, Drexel University’s student-run record label, and Vinyl Me, Please released Laugh to Keep From Crying, the Nat Turner Rebellion’s long-lost debut. It is a welcome psych-tinged funk-soul-brother addendum to The Sound Of Philadelphia time capsule that feels even more relevant half a century after it was recorded.

amongst a trove of unclaimed Sigma Studios recordings that had been gifted to the school back in 2005. On March 29th, MAD Dragon Records, Drexel University’s student-run record label, and Vinyl Me, Please released Laugh to Keep From Crying, the Nat Turner Rebellion’s long-lost debut. It is a welcome psych-tinged funk-soul-brother addendum to The Sound Of Philadelphia time capsule that feels even more relevant half a century after it was recorded.

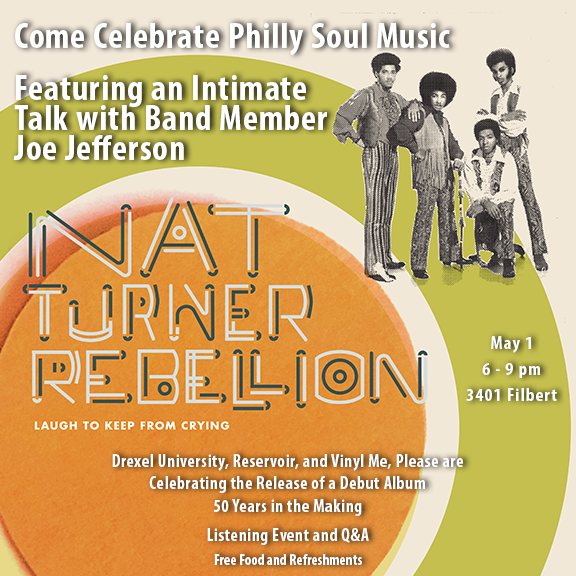

To mark the occasion, Drexel/Mad Dog Records is hosting a record release listening party on Wednesday May 1st from 6-9 pm at 3401 Filbert Street and everybody’s invited! There will be free food and refreshments and Nat Turner Rebellion’s Joe Jefferson will be giving an “intimate talk.” Recently, I spoke with Drexel Audio Archives Director Toby Seay about Nat Turner Rebellion’s Laugh To Keep From Crying, audio archiving, the historical context and importance of the album, what merits it has to contemporary listeners, Drexel’s music program, The Sound of Philadelphia, and more.

PHAWKER: Could you start by explaining how this project came about?

TOBY SEAY: The project came about when Reservoir Media and Faith Newman struck a deal to buy the record catalogue of the defunct Philly Groove record label. One of the issues we have in our archive is that, while we own all these tapes, we don’t own any of the content that’s recorded on them. So, we have to be really careful with what we can do with it. So as far as with album releases and that kind of thing, it’s rather difficult. And so when Faith called and said, “Hey. We just purchased this record label. We’re wondering if you have any of the recordings in your collection,” I knew we did. “There’s a lot of Nat Turner here! It’s really good!” I said. And they started to think about what they could do with it. So it’s been years in its development, but that’s kind of how it got started. And then we had all the tapes digitized and kind of assessed what we had, Faith reached out to Joe Jefferson from Nat Turner Rebellion and struck the deal with him to get the OK to do it, and we were up and running.

PHAWKER: Tell me about the donation of archival material that Sigma Studios made to Drexel? What are the names of the artists in the archive that they gave you?

TOBY SEAY: I think the deal was finalized in ‘05 when it was donated it to us. As far as the stuff that’s in there, it’s a lot of leftover stuff, but there are some significant names. You have David Bowie. You have Stevie Wonder. You have a lot of early stuff that was in the rock world. And you have a lot of Teddy Pendergrass. Grover Washington Jr and Patti LaBelle. It’s a lot of significant names. Some of them are simply safety copies of the master or they might be the outtakes of songs, or recordings that didn’t make the album. For the most part, the Philly International records and the Philly Soul hits are in the possession of Philly International, so we don’t have those. But it’s a really interesting picture of how much work happened in that studio. And then you have stuff like this with the Philly Groove project—Nat Turner Rebellion. They were on a small label that had gone defunct, and that stuff stayed there.

PHAWKER: Can you provide some historical context to all of this, specifically to the time when these tracks were first recorded and the Black Panthers were clashing with Rizzo’s cops in the streets of North Philly? Does this project speak to the now as well as the past?

TOBY SEAY: I think what’s really intriguing about this particular project is exactly what you’re describing. The fact that there’s a band that was willing to put “Nat Turner” in their name in the ‘60s—that alone makes a statement. Now, if you listen to the music, a lot of the music isn’t what you would necessarily call protest music. There’s not a lot of overt Black Power messaging there. “Tribute to a Slave” is one example that kind of does, though; it kind of just speaks to Nat Turner and the presence and legend of him within the community. But some of the songs are just traditional love songs and songs about getting high.

But that also kind of paints a picture of a situation where the record label was pushing them to be more like The Delfonics, so they could sell more soul records. You could tell the band wanted to be a little more aggressive, and a little more like Sly Stone. So you can kind of see that angst between the record label and the band. But on top of that, you also have songs that kind of paint them as hippies. They were a band that you can’t put in a box.

At the time, I think that’s why the record label struggled. On the other hand, I think when we look back at it 50 years later, it shows us that people are complex. People can be Black Power and “soul” at the same time. However, the other part of this project that made it interesting was the emergence of the Black Lives Matter movement. So, while that was happening, we had Ferguson. The music sounds fifty years old, but the lyrics could have been written this year! So, there’s a couple of ways to look at that. For me, it’s kind of sad that, fifty years later, the themes are still current; it makes it look like as a society, we haven’t progressed much. But on the other hand, it also kind of shows that there is a timeless nature to the music as well. The music is still incredibly enjoyable to listen to. It’s interesting—fifty years old, and it still has currency.

PHAWKER: Nowadays, you could call your group Nat Turner Rebellion and, for the most part, you would probably be praised as socially conscious, and as someone who is honoring past heroes. Back then, I’m sure that was a seriously risky statement to make, though.

TOBY SEAY: Not only that, but there’s a picture that Joe Jefferson showed me of [his stage costume]. When he would go onstage, he would be the persona of Nat Turner. He would go onstage with a noose around his neck! And, as you were saying, you do that now, and there’s some theatrics to that. But that takes some courage to do that in 1969. It makes a huge statement.

PHAWKER: Let’s talk about Drexel’s music program. Could you explain the program/class  where students get to play record company moguls? That sounds like a fun class.

where students get to play record company moguls? That sounds like a fun class.

TOBY SEAY: Our desire is that our program is a holistic music industry program. We cover all of the business aspects of the music industry, and we cover the technical, music production side of the industry. There is a lot of overlap. Production students will take business courses and business students will take production courses. But we do have the record label—Mad Dragon Records—which is part of a larger, student-run business called Mad Dragon Music Group. They deal with publishing, licensing, live video management, etc. So it covers a lot of areas that are pertinent to music business. The student-run record label is releasing this album. On top of that, we have courses that delve into “moguls.” We have a course that looks at music industry moguls over the years in some of the biggest practices. There are courses in copyright, they do a lot of business courses out of the business school, and there are a lot of music courses out of the music department. The hope is to provide a very broad arsenal of music industry knowledge. I feel like we do a pretty good job of delivering that.

PHAWKER: Last question, what’s become of the guys in Nat Turner Rebellion?

TOBY SEAY: After the band kind of fell apart in ‘73, a couple of things happened. One was that Joe Jefferson, who is the only surviving member and the impetus behind the entire band, had become known as a songwriter. And so he went on to have a very wonderful career as a songwriter. He wrote a number of hits for The Spinners. He had a long career as a songwriter and a producer after the fact. The other member of the band that went on to notoriety was Major Harris. During his time in the Nat Turner Rebellion, he learned to sing. And he kind of became groomed and pushed as a solo artist. He had a solo career and sang with some other groups. He was a very significant person in the world of soul music. If you ask anybody familiar with the soul genre, they know who Major Harris is, because he had an artist’s career. Joe Jefferson had more of a writer’s career, so not as many people know his name. As for the other members, honestly I don’t think they went on any further than Nat Turner Rebellion. I think that was it for them. But Major Harris and Joe Jefferson went on to significantly impact the soul scene.