EDITOR’S NOTE: This story originally published on March 30, 2015.

BY JONATHAN VALANIA FOR BUZZFEED: Most people don’t know it, but there are actually five, not four, time zones in the United States: Eastern, Central, Mountain, Pacific, and Isaac time — as in Isaac Brock, singer, guitarist, chief songwriter, and all-around mastermind of the very popular underground major-label rock band Modest Mouse. The Isaac time zone is usually situated within the city limits of Portland, Oregon, where he resides, but point of fact it’s located wherever he’s standing at the moment. Isaac time is kind of like bullet time in The Matrix, only slower. Or better yet, it’s like that scene in Interstellar where they explore that water planet orbiting a black hole for 20 minutes, and by the time they get back to the ship, 20 years have passed on Earth.

BY JONATHAN VALANIA FOR BUZZFEED: Most people don’t know it, but there are actually five, not four, time zones in the United States: Eastern, Central, Mountain, Pacific, and Isaac time — as in Isaac Brock, singer, guitarist, chief songwriter, and all-around mastermind of the very popular underground major-label rock band Modest Mouse. The Isaac time zone is usually situated within the city limits of Portland, Oregon, where he resides, but point of fact it’s located wherever he’s standing at the moment. Isaac time is kind of like bullet time in The Matrix, only slower. Or better yet, it’s like that scene in Interstellar where they explore that water planet orbiting a black hole for 20 minutes, and by the time they get back to the ship, 20 years have passed on Earth.

If you want to experience it for yourself, you really need to go to Portland. Once you arrive, proceed directly to the Ice Cream Party, a three-level mid-century modern structure situated in Portland’s Goose Hollow neighborhood in the shadow of Providence Park soccer stadium that serves as recording studio, rehearsal hall, storage space, living quarters, and band hangout — it is, in short, Modest Mouse’s Batcave. As instructed, you type in the secret code into the keypad and are ushered in by one of Brock’s henchmen, and then you wait and wait and wait, because, well, time is irrelevant to Isaac Brock. Always has been.

His manager, a very nice and helpful fellow named Juan, says Brock called to say he’s waiting for a locksmith and is going to be late. A locksmith for what exactly he does not say. So you do what the rest of the band are doing: hang around a table in the center of the Ice Cream Party, shooting the shit, nipping beers and coffees. Some are smoking cigarettes, others smoking something stronger. (Marijuana is technically legal in Oregon, but won’t be available at state-sanctioned shops until July, not that anyone’s waiting around.) […]

Brock, 39, finally shows up a couple hours later in a beanie and a hoodie, bleary-eyed and red-nosed,a devilish grin splitting his ruddy, lived-in face. He’s been fighting a nasty cold for weeks, he says, and the cold remedy he’s been pounding has rendered him out of it. “I’m sorry, my brain is so unbrainly right now,” he says. He speaks with a slight lisp. (“I like hearing him talk, doesn’t he have the coolest speaking voice?” comedian Fred Armisen texts back when asked about Brock’s appearances on Saturday Night Live and Portlandia. “I mean singing, too, obviously, but I can listen to him tell a story all day.”)

Modest Mouse are supposed to start rehearsing for their impending tour around 2 that afternoon, but it’s almost midnight by the time they finally plug in and start playing. It is not long before someone points out that midnight is a crazypants hour to start rehearsing, and they give up after 30 minutes or so. But not before nailing the positively epic chorus of “Of Course We Know,” the grand finale from the new, eight-years-in-the-making album Strangers to Ourselves.

The next day I show up at the appointed hour of 2 p.m. and join the other knights at the round table and start all over again. Coffee. Beer. Mary Jane. Rinse and repeat. A couple hours later, Juan taps me on the shoulder and says Brock is on his way, that he fell asleep putting on his socks. This sounds plausible, I tell myself, because I want to believe. Eventually he shows up and I get time to ask Brock questions. Lots and lots of time. Because I’m now standing in the Isaac time zone, where every minute is like 20 years back on Earth.

“Even when I was a kid, I always showed up late for school every day,” says Brock, his tone somewhere between a shrug and a boast. “It got to the point where they had my late slips filled for every day of the school year in advance, so all they had to do was fill in what time I got there.”

Some rock stars are happy to hit their mark and feed you their talking points like trained seals. Brock despises craven self-promotion and easy answers, preferring instead the gentlemanly arts of wit, whimsy, and conjecture, preferably of the surreal variety, wherein no point is ever arrived at until at least five or six fascinating detours from the subject at hand have been explored. Sometimes the point gets completely lost and we have to send out a search party. And that takes time. Lots and lots of time. Twelve hours straight, to be exact. It’s like mainlining Modest Mouse.

“My world is so fucking insane and shit I don’t even want to be interesting any more — write a boring fucking story about me because I’m sick of being interesting,” he tells me somewhere around the eight-hour mark. “I’ve killed myself making this record. Fuckin’ literally thought I was going to die. I wrote a will on an airplane, and I was like, I know I’m dying.”

I try to draw him out on the new album, but Brock’s not ready yet. He takes a slug from his bottle of cider, his drink of choice these days because it doesn’t give him a hangover. He’s going to need to down a few more, he says, before unpacking the agonies and ecstasies of gestating the new album. “Thinking about the record is hard for me,” he says, “because every little fuckin’ freckle on this thing I would look at with a magnifying glass, and then decided I needed to look at it from the top of a fucking mountain. My ability to have a perspective on it is so far gone, along with everything else. When the record was done, I was told, ‘You made $200 last year, you’re pretty much broke.’”

After an eight-year hermitage of trial and tribulation, of endless woodshedding, endless recording and erasing and re-recording, of beauty, repetition, and noise and danger and boredom and bloodletting — which is apparently just a day in the life of Isaac Brock — there is a new Modest Mouse album, Strangers to Ourselves. “Eight years is a long time between albums, I mean, there were three children born to members in that time,” says Brock. “But the good news is that I’m not sick of a single song on here and after working on them for five years, I think that speaks for itself.”

There is blood in these tracks, and there be monsters too. There is a lot is riding on there also being money in these tracks. In 2004, Modest Mouse had a huge, if improbable, hit with “Float On” — a shuffling, arpeggiated ode to walking between the raindrops of life’s shitstorms — that drove sales of Good News for People Who Love Bad News, the album it came from, through the roof (it went just short of double platinum — nearly 1.9 million copies in the U.S.) and put a shit ton of mainstream asses in seats. But a lot has changed in the intervening 11 years. In 2015, the incredible shrinking music business is fully half the size it was in 2004. The mass audience that bit hard on “Float On” may have aged out of the concert-going demo. All of which is surely cause for a lot of nail-biting and gnashing of teeth inside Modest Mouse Inc. “A lot of people are counting on me, people with families,” says Brock. “And nobody pays for music any more.”

Brock’s been running the media gauntlet in advance of the new album’s release and everyone wants to know why it took eight years to follow up 2007’s We Were Dead Before the Ship Even Sank. Everyone. It’s a reasonable question. After all, a lot can happen in eight years. The Beatles came and went in eight years. But there is no single answer. “I have eight answers to that question,” says Brock. “And I believe them all!”

In the last eight years, Modest Mouse chewed up and spit out four record producers (including Big Boi from OutKast), two mixdown engineers, their bass player, plus Nirvana’s bass player, who auditioned to replace him, not to mention the guitar player from The Smiths. In that time, the band racked up 30-plus songs, enough to flesh out the new album with a fairly whopping 15 songs as well as a follow-up album tentatively set for release in mid-2017. Two and a half years of that eight-year span were spent touring We Were Dead. The year after that was supposed to be a year of rest and relaxation, but the band wound up playing another 60 shows.

From there, the first of many, many woodshedding sessions commenced in the hopes of generating material for a new album. “Eight years is a long time between albums, by any measure, but it’s not like there was a lot of downtime,” says guitarist-songwriter Jim Fairchild, Modest Mouse’s second guitarist for the last six years, during a break from not rehearsing. “There were tons of writing sessions. One thing I learned about Isaac is he doesn’t settle. I’m not exaggerating when I say I heard at least 50 riffs that could have been really good Modest Mouse songs, but for whatever reason he wasn’t satisfied. There really was no downtime.”

Then came a devastating loss. In 2011, with most of the new album written and ready to record, charter bassist Eric Judy tendered his resignation, after 18 years of service, without explanation. This was a huge blow. Judy’s departure tore a big hole in the DNA of the band’s sound. “The way those three guys play is Modest Mouse, to this day,” says Fairchild on another break from not rehearsing. “Nothing can ever replace that bond.”

Brock thinks Judy simply had enough of the grinding stress and isolation of yearslong recording and touring cycles. “Eric and I weren’t without our problems,” he says. “But I’m not sure that this path was exactly what Eric wanted — being in a band touring all the time and all that stuff. I don’t think that he ever fully signed on in his mind to what this life requires.”

Perhaps, but Judy’s reluctance to revisit the last 23 years of the Modest Mouse saga suggests there’s more to it than that he just wanted to spend more time with the wife and kids. Judy originally agreed to to be interviewed for this article via email but then changed his mind, writing, “I appreciate your wanting to include me in the Modest Mouse article but I don’t think I’d like to be a part of it. I left the band because of the anxiety it was causing me and it’s been hard to get myself back on track. I didn’t realize I’d feel so bad reading the questions.”

Three years ago, Brock purchased the building that would become Ice Cream Party. Work on the new album paused for months on end as Brock and Co. installed a recording studio, living quarters, kitchen, rehearsal space, offices for both Modest Mouse’s management and Glacial Pace (Brock’s record label), and vast hangout zones centered around a pair of tables and a few stools that host band meetings and endless shoot-the-shit sessions. As any band will tell you, having your own studio is both a blessing and a curse, easily turning a finite recording schedule into infinite jest. You have endless time and an infinite number of choices, and that way lies madness. “Options are a motherfucker,” says Brock. “Most of the best music in American history was made by people with no options. It’s like, I was hungry so I built a restaurant when I should have just ordered off the menu.”

Once the recording studio was up and running there were at least four different recording sessions — some lasting weeks, other lasting months — with different producers, with Brock sometimes scrapping all that had come before, other times building on what was worth keeping. The recording was completed in November 2013. Brock spent all of 2014 mixing the album with Chicago post-rock guru John McEntire (Tortoise, The Sea and Cake), only to scrap those mixes and complete the project with Joe Zook (Katy Perry, Pink), who had mixed We Were Dead Before the Ship Even Sank.

It took 23 years, but Modest Mouse is no longer a boys-only club with the recent addition of violist Lisa Molinaro, who is not just a newly minted member of the band, she is also Brock’s romantic partner of the last five years. The two met five years ago and Brock soon signed her band Talkdemonic to Glacial Pace, his in-house record label. When Talkdemonic called it quits, Molinaro became a full-time member of Modest Mouse. As such, she’s had a front row seat for the trials and errors and, ultimately, triumphs of the past half decade. She claims, somewhat improbably, that if she had to do over again she wouldn’t have it any other way. “It has been a strenuous couple years for Isaac and the band and as a result for our relationship — and that’s been hard,” she says. “But I am committed to Modest Mouse and I am committed to him and our relationship and that takes an ultimate amount of patience, which luckily I have lots of.”

Still, it’s one thing to invite female energy into the band, it’s quite another to make your girlfriend a full-time band member and the two years Modest Mouse will spend on the road promoting the new album will surely test their union.”Up until now I had a pretty hard-and-fast rule: Never be in a band with a person I’m dating,” says Brock. “It was a pretty easy rule to follow considering who was in my band. I couldn’t do it with a lot of people, but I can do it with her.

“I’m not the easiest dude to deal with. So she might decide that she can deal with my bullshit, and she might decide that she can’t. For me, it’s not much different than just having another person in the band. She’s an A-student–type person. And I’m an awesome student, I just don’t do much work or show up. A-students keep track of tone and timing and things. Davey [Massarella]’s an A-student and Ben [Brozowski]’s an A-student. None of them have been in the band that long. They’ll lose their grip soon enough. They always come in as A’s, and everyone leaves as an F.”

Brock’s family tree is a riot of boughs, branches, and deadwood sprawling across the endless grassy plains of the lonesome crowded West. “If I wanted to count divorces and separations, on paper I have something like 16 or 18 fucking stepbrothers and sisters,” he says as we tool aimlessly through Portlandia in his metallic green Land Cruiser. “The guy who kind of identified as my dad was my dad’s brother, who was the second person my mom married. [She] left my dad for his brother. It was a family feud for a while — for something like 17 years there was two brothers not talking.”

Brock is wary about talking about his childhood, because the more outlandish anecdotes he shared with journalists early on — the commune! the trailer park! the Christian death cult! — have become part and parcel of his lore and legend and are often misinterpreted as indicators of hardship and neglect, much to his mother’s chagrin. Which, I suppose, is why, without prompting, he insists I drive up to Issaquah, the leafy exurb of Seattle where he grew up, to speak with her in person and set the record straight.

Issaquah is a quaint Twin Peaks-ian burg situated in the foothills of the Cascade Mountains. Low-hanging clouds make it feel nearer the sky. When Brock was growing up, Issaquah was the master of its own domain, but it’s long since been engulfed by Seattle’s vast suburban sprawl and all the plagues of postmodernity that Brock railed against on The Lonesome Crowded West: overdevelopment, chain-store mallification, gridlock.

Kris Adair, Brock’s mother, lives in Issaquah with her husband of 20 years, Michael Adair, who immediately gets put on the Cool List — he saw both Jimi Hendrix and legendary ‘60s garage punks The Sonics back in the day.

The Adairs live in a charming teal chalet with plum-tone trim and magenta doors. They built it out of Douglas fir with their own hands, in the artfully landscaped footprint of the house that repeatedly flooded when Brock was growing up. The hallways of Chez Adair are lined with Modest Mouse gold records. Serena MacDoodles, the Adairs’ Maine coon cat, scampers by as we settle into the living room to sort out the facts and fictions of Brock’s childhood.

“His stories are born, in part, of his memories as a child,” says Kris Adair. “And though they may be fractured memories and sometimes not completely accurate in chronology, they were his perception and truth at the time. Isaac isn’t necessarily a linear kind of fellow. You have to get used to that when you talk with him. He is fortunate to have such a great outlet in his music and lyrics. I think that is why his music has such a strong impact on people, because he speaks to the oft-times fractured human condition so eloquently. Nonlinear works in lyrics, but in interviews not so much.”

Far from being the white-trash, trailer-park motorcycle mama implied in many an article about Modest Mouse, Adair is a bright, generous, and righteous lady who kept her son on a long leash, giving him the space and patience he needed to figure out who he wanted to be and how to become that person. For a wild child like Brock — brilliant, driven, and artistically inclined — there was no greater gift a mother could bestow on a son. In Issaquah, the fruit does not fall too far from the tree. Like her son, Adair is a seeker, with a long track record of youthful experimentation with a broad range of perspectives, lifestyles, and worldviews. Some might perceive her parenting style as overly permissive, but both she and her son agree she merely gave him enough rope to climb his way out of Issaquah and into the big time.

There are four whoppers that emerged from what she calls “the hodgepodge of articles written about him” and have coalesced into the Wikipedian hive-mind narrative of his childhood that she wants to truth-squad:

MYTH: Before Brock was born in 1975, his mother was a member of the White Panther Party — the radical white-hippie analog to the Black Panthers — whose rallying cry was “rock and roll, dope, and fucking in the streets.”

REALITY: Technically true, but it wasn’t like that. “I left home when I was 17 years old and through a friend I was given a safe place to live by a White Panther collective,” says Adair. “They were not happy to have an underage liability on their hands, but luckily for me they were not willing to put me on the street either. I learned how to advocate on behalf of our elderly neighbors whose homes were threatened by developers.”

MYTH: Brock grew up in a “free love” hippie commune.

REALITY: Hardly. When Brock was 3 years old, his parents split and his mother married her ex-husband’s brother. “We lived very briefly — but were not part of — the ‘commune’ called Great Oaks in Oregon,” she says. “They lived in yurts and we wanted to learn how to build our own. They were also into raw foods, fasting, and enemas — we were not. Isaac stayed there a grand total of one night.”

MYTH: Brock grew up in a crazy Christian death cult spin-off of the infamous Branch Davidians, the armed apocalyptic sect that perished back in 1993 when their compound in Waco, Texas, burned to the ground after a 51-day standoff with the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives.

REALITY: “Baloney,” says Adair. “The name of the church was Grace Gospel in Valier, Montana, and it was fundamentalist and very right-wing — probably created a lot of tea partiers, god forgive me! — but had nothing to do with the Branch Davidians.”

MYTH: When the family house in Issaquah got washed away in a flood, Brock was banished to the backyard shed, where he lived out his childhood.

REALITY: Half-true. There was a flood and the family was displaced for a time, but the house did not wash away — it was just full of mud. Brock opted to live in the shed instead of the tiny trailer his mother, sister, stepfather, and stepbrothers and sisters lived in while working on cleaning up the house and making it livable again. The shed became Brock’s tree fort and artistic laboratory, and it was there that he taught himself to play bass and, later, guitar. The shed also served as the manger where Modest Mouse was born, when once upon a midnight clear Jeremiah Green’s deep kick first locked in with Eric Judy’s lambent bass thrum as Brock’s ecstatic guitar squeal and shrieking tantrum of a voice exorcised the ghosts of Surfer Rosa and Nothing’s Shocking lurking in the rafters. As such, it is the Rosebud in Modest Mouse’s creation myth.

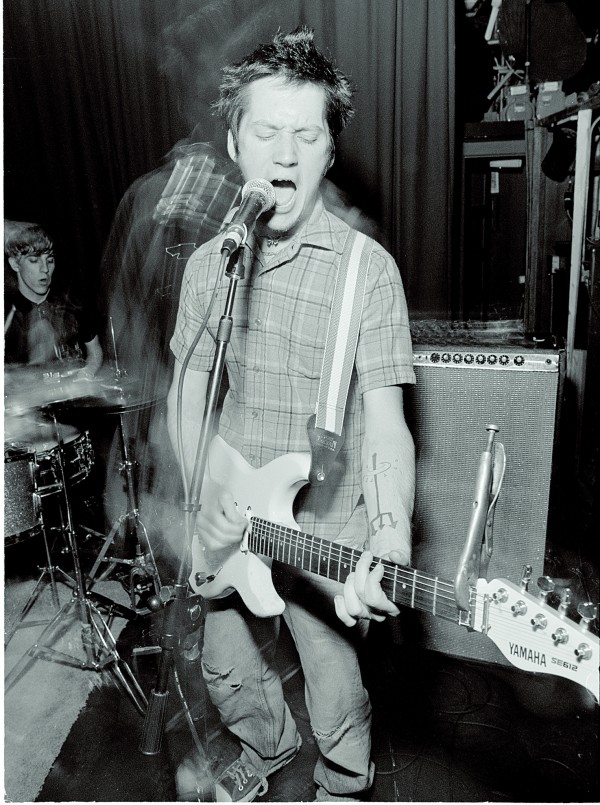

The trajectory of Modest Mouse’s career from tenderfoot punks from Podunk to kings of the post-grunge Seattle scene was fairly meteoric. Not that they didn’t pay their dues. They ran their laps around the indie-rock stations of the cross: They played house parties until the cops came, they slept on the floors of strangers, they ate out of gas stations, they drove 22 hours through the night, in the snow, uphill both ways, to play for three people in Cow’s Ass, Indiana, like they were playing the Hollywood Bowl.

But hordes of young bands do that and never wind up with Modest Mouse’s career. It takes more than heart and stamina and an indifference to the smell of one another’s farts and a willingness to eat Cheetos for dinner. You have to have that X factor — that lightning-in-a-bottle combination of charisma, genius, and luck. Modest Mouse had it all, almost right out of the gate. It takes some bands 10 albums to turn out a “Dramamine,” and other bands make 10 albums and never get a “Dramamine,” but for Modest Mouse, it was the first song on their first album, This Is a Long Drive for Someone With Nothing to Think About.

“It was clear right away that Modest Mouse was going to stand out from the herd,” says Sean Nelson, arts editor for Seattle’s alt-weekly The Stranger. “There were quite a few young bands from the Pacific Northwest suburbs who were cultivating the indie-punk sounds that would become a lot more familiar as the ’90s wore on, and a surprising number of them were really good, but Modest Mouse were obviously in their own league. In a weird way, they sort of put Seattle — which for all the success of the early ’90s was still kind of provincial — back on the map as a site of truly interesting, meaningful, new rock music. Then they made The Lonesome Crowded West, which was the first blatant masterpiece LP any Seattle band had made for a long time. It was a while before other bands caught up.”

The Lonesome Crowded West put Modest Mouse on the indie-rock map. It also made them a target. More specifically, it made Brock a target — not that the Wild Man of Issaquah didn’t often go the extra mile when looking for trouble. “Back then he was just crazy, super high on so many things,” says Blessed Light frontman Toby Gordon, who has been part of the Seattle music scene since the early ’90s. “He was always getting in people’s faces; he was fearless. And he went out of his way to find trouble. I once saw him pick a fight with a whole gang of dudes walking the opposite direction across the street.” To the casual observer, it would appear that Brock saw the world as a giant fist and it was his job to get out of bed every day and run face-first into it.

Around the same time, the Jackass guys were getting paid to be human cannonballs. For Brock, it was just a hobby. There was the time he got drunk and herniated three discs falling from a third-story balcony onto a second-story balcony. There’s the time he got his face bashed in with a beer bottle in Nottingham, England, that fractured his eye socket so severely doctors had to screw a plate into his skull. And the hits just kept coming. There was the time in Chicago when the band were recording The Moon & Antarctica, their 2000 major-label debut, and Brock tried to make friends with the local toughs drinking in the park and was gifted with a shattered jaw for his trouble. “My jaw felt pretty loose and weird — turns out they knocked it off the hinge,” he says. “There is a plate in my chin from that one. I still can’t feel that part of my face when I touch it.”

His jaw had to be wired shut for weeks, rendering singing nearly impossible — until he was done with having his jaw wired shut and, the night before Coachella, yanked out the wires with nothing more than Leatherman pliers and a bottle of whiskey for anesthesia. It took an hour and a half of cutting and yanking and bleeding. He does not recommend it. “I needed a lot of dental work afterwards,” he says.

But all those bone-crushing blows would seem like love taps compared to the hit that was coming.

One morning in the early spring of 1999, Brock woke to find that somebody had written R-A-P-I-S-T in big letters on the side of Modest Mouse’s touring van parked outside of his house in the desolate Interbay neighborhood of Seattle. This development was not entirely unexpected. The week prior The Stranger, Seattle’s alt weekly, had splashed across their front cover a story by Samantha Shapiro revealing the news that Isaac had been accused of date rape by a 19-year-old woman, a familiar face in the Seattle music scene, after a night of drinking at the Cha Cha Room. The news ruptured the close-knit Seattle music scene, immediately dividing it into two camps: those who believed Brock and those who believed the alleged victim. Brock doesn’t dispute the fact that they had intercourse. He thought it was consensual; she insisted otherwise.

There was a charged vibe in the Cha Cha Room that night, according to several people who were there but asked not to be identified, an indistinct but unshakeable feeling that something was afoot. At one point, the alleged victim and her ex-boyfriend went into the bathroom to talk, reportedly about reconciling, but it was not to be. When she emerged, she made a beeline for Brock’s table. He invited her to join him and, even though she was underage (the drinking age is 21 in Washington), they drank until closing time.

This is Brock’s version of what happened next: When the bar closed, he offered to walk the young woman home. Halfway to her apartment, she suddenly remembered she forgot her keys. So instead, they went back to the tiny, 400-square-foot house he shared with then-roommate Sean Hurley— who wrote a letter to The Stranger calling her story about that night “a complete fabrication.” Hurley and Brock’s rooms were right next to each other and shared a wall.

Hurley remembers hearing Brock in his bedroom next door whispering, “We have to be quiet, or we’ll wake up my roommate.” Hurley lay awake for a while, and never heard anything that sounded like someone was in distress. He fell back to sleep. Brock says he and the woman had consensual sex and afterward walked a quarter mile together to the nearby QFC grocery store for some late-night snacks. Brock remembers the woman making a phone call on the pay phone and having a brief conversation with somebody. But he hung back, giving her some privacy, and has no idea who she called or what was said. They then walked the quarter mile back to Brock’s house, ate the snacks, and fell asleep. Hurley was up early the next morning working on his computer in the living room. He remembers the woman emerging from Brock’s bedroom around 10 a.m. and leaving in a cab without saying anything.

“Let me be clear that it is not my point of view to question women who report rapes,” says Hurley today. “Sexual violence is rampant, common, and a horrible problem. Having said that, Isaac was shattered. It was a big part of his persona to be someone who stood up for women’s rights, and [he] railed against sexual violence.”

(Voicemail messages to the woman were unreturned at press time.)

The young woman filed a criminal complaint with the Seattle Police Department. Brock was interviewed twice, both times over the phone. He was never arrested, fingerprinted, or photographed. The Seattle Police Department and the King County Prosecuting Attorney’s Office expunge files after five years as per the policy for cases where charges were never filed, and therefore a police report no longer exists. “Charges were not filed because there was insufficient evidence of a crime,” Dan Donohoe, spokesperson for the prosecuting attorney’s office, told me.

The Stranger‘s handling of the allegation was almost as controversial and divisive as the allegation itself. “I was going to sue [The Stranger’s Editorial Director] Dan Savage,” says Modest Mouse drummer Jeremiah Green. “I called him up and left a message saying ‘WTF putting MODEST MOUSE RAPE STORY on the front page of the paper?! I’m gonna sue you!’ He called me back and gave me his lawyer’s number and apologized.”

The Stranger published a follow-up story in late June 1999, pointing out that charges had yet to be filed, and quoting the lead investigator on the case saying he doubted charges ever would be. The paper vowed to follow the story to the bitter end, but would never write about it again. Both stories about the alleged rape have since been scrubbed from the paper’s website, and Brock recalls visiting The Stranger‘s office a couple years later and seeing the cover of every issue ever published hanging on the wall — all except the one that almost singlehandedly tattooed “RAPIST” on his forehead.

Savage responded to my request to interview him about the matter with the following email:

i don’t recall what exactly went down — this was a long time ago. i didn’t become the editor of the paper until 2001. i was never the paper’s managing editor, and we’ve always had a news editor. the news editor would’ve been the person [Samantha Shapiro] reported to. i don’t recall what i might have said to her in passing about it.

sorry i can’t be of more help. this was a long time ago.

He did not respond to follow-ups.

“I was really hoping for a trial,” says Brock. “Because I was certain the facts would acquit me and this thing would be put behind me. Instead, it’s like a dark cloud that follows me wherever I go. I can’t outrun it: I doubt I’ll outlive it.”

Googling “Isaac Brock rapist” returns 29,400 links. Brock says he never filed a defamation lawsuit because he “didn’t want to give the story more oxygen and didn’t want to ruin that woman’s life just because she made a dumb mistake when she was 19.” A year later, when Modest Mouse pulled up to the venue they were playing in Boise, Idaho, there were protesters holding anti-rape signs picketing out front. “I remember thinking that, a year ago, I would be out there with them,” says Brock. To this day, 16 years later, Brock says, “Whenever I walk into a bar, by conservative estimate, fully 40% of the people in the room think I’m a rapist. Or at least it feels that way, and that’s a really shitty feeling.”

In 2002, while driving through Lane County in southern Oregon, Brock blacked out behind the wheel while huffing nitrous oxide and crashed his van into the center median. “What can I say? I make poor decisions,” he says with a shrug. One of Brock’s passengers, an unnamed female, dislocated her thumb. Brock likes to tell people he was charged with attempted murder because of the way the DUI laws are written in Oregon — if someone is injured, even slightly, in the commission of a DUI, the driver is slapped with an attempted murder charge.

That’s not true, says Deborah Green, deputy district attorney for Lane County, who tells me Brock was charged with a DUI and, as per Oregon state law, fourth-degree assault because somebody was injured as a result of his driving under the influence. Brock says he hired an attorney to handle the matter, but that lawyer never bothered, and, unbeknownst to Brock, an arrest warrant was sworn out in his name. Brock discovered this upon returning from a day trip across the Canadian border to see Niagara Falls when he cocked off to a border guard and they ran his name for warrants, slapped the cuffs on him, and put him on ice for two weeks until he was extradited back to Oregon. He wound up getting off with a few weeks of doing roadside cleanup in an orange prison jumpsuit.

Tragedy did not discriminate in its headlong pursuit of Modest Mouse. Sooner or later it would find every member. In 2003 it was Green’s turn. “I lost my shit,” he says, during yet another break from not rehearsing. “I started taking this antidepressant called Effexor, and they made me go totally manic. It was like being on a low dose of ecstasy every day. I loved it. I felt great. But it made my life weird. On top of all that I was eating magic mushrooms almost every day.”

Right before recording sessions commenced for Good News for People Who Love Bad News, the album that would break them into the mainstream and grow their fanbase exponentially, Green abruptly quit the band. “About a month after I quit, Isaac was calling my girlfriend and my mom, checking up on me. Most people thought I was just a freak and being weird, but Isaac realized this was something serious. So I listened to my mom and went to some mental institution for, like, six hours, because people suggested that I should do that.”

By the time Modest Mouse were about to commence touring in support of Good News for People Who Love Bad News, Green was back behind the drum kit. But even though there was a happy ending to Green’s flirtation with the edges of sanity, tragedy continued to stalk the band.

On the new album there is a song called “Ansel.” It’s about Brock’s adopted brother, Ansel Vizcaya, who was killed in 2004 by an avalanche while climbing Mount Rainier. It took six days to find his body. He was the 81st person to die on the mountain since the National Parks Service started keeping track of fatalities back in 1897. The song isn’t so much about Ansel’s death as about the last time Brock saw him, what went down, and the fact that Brock never got the chance to make things right with his brother before he died.

“About a year before he died, me, my dad, and Ansel met up in Puerto Vallarta [Mexico],” says Brock, somewhere around the 11th hour of our interview. “We all flew from different places, and it had been years since all three of us hung out together. I remember wandering around and bumping into some scumbag there and wound up buying cocaine off him and doing that with my brother. We leave Puerto Vallarta and go to another town that I can’t remember and me and my brother bump into some other nice dude on the beach and start doing drugs with that guy. My brother was smart enough to call it a night.”

Brock didn’t call it a night for another three days. By then he was in the throes of full-blown paranoia and hallucinating vividly. “I remember looking out the peephole and I could see these three fucking guys in skull masks. Basically, I thought the town was rolling in to kill me. My dad was surprisingly cool about the whole thing, but I could tell Ansel was really bothered. That was the last time I saw the guy, was on that trip, and I always assumed there’d be a point in time where it’d be water under the fucking bridge. I didn’t realize that the bridge was collapsing.”

Back at the Ice Cream Party, the sun is starting come up. We are in the 12th and final hour of what has proved to be a long, dark night of Brock baring his soul. The ashtray is overflowing with smoked-to-the-filter American Spirits. A Berlin Wall of empty cider bottles has been slowly erected between us. And he tells me he has a confession to make: The day before, when he showed up hours and hours past his expected arrival time, it wasn’t because he was waiting around for the locksmith. That was a little white lie. The reason he was so late was he just had to get the fuck out of Dodge. “I don’t get any time to myself, ever,” he says, suddenly sounding tired. “I’m working on shit all the time or taking care of something for the band or my label. So I disappeared. I just drove. I just wanted to get out of my head.”

He wound up in Timber, Oregon, a tiny mill town (population 131) situated 40 miles northwest of Portland on the edges of the Tillamook State Forest. He likes to go there and pick morels when he needs to get away from the constant demands of being Isaac Brock. Timber is located deep into logging country, far from public view, and there are entire mountainsides that have been rendered barren and moonlike by clearcutting — which Brock absolutely loathes. He wants to use one of these defoliated mountains as the location for shooting a video for the song “Pistol” from the new album.

A ray of sunlight streams through the large windows of Ice Cream Party and chases away the shadows from Brock’s haggard face. He lets out a long exhale, sits up straight, and, for the first time all night, he smiles. He seems relieved to have confessed his sin, as if honesty is its own absolution. “The truth is pretty fucking badass,” he says. “Nothing’s scarier than the truth.”